[THREAD: ZERO]

1/51

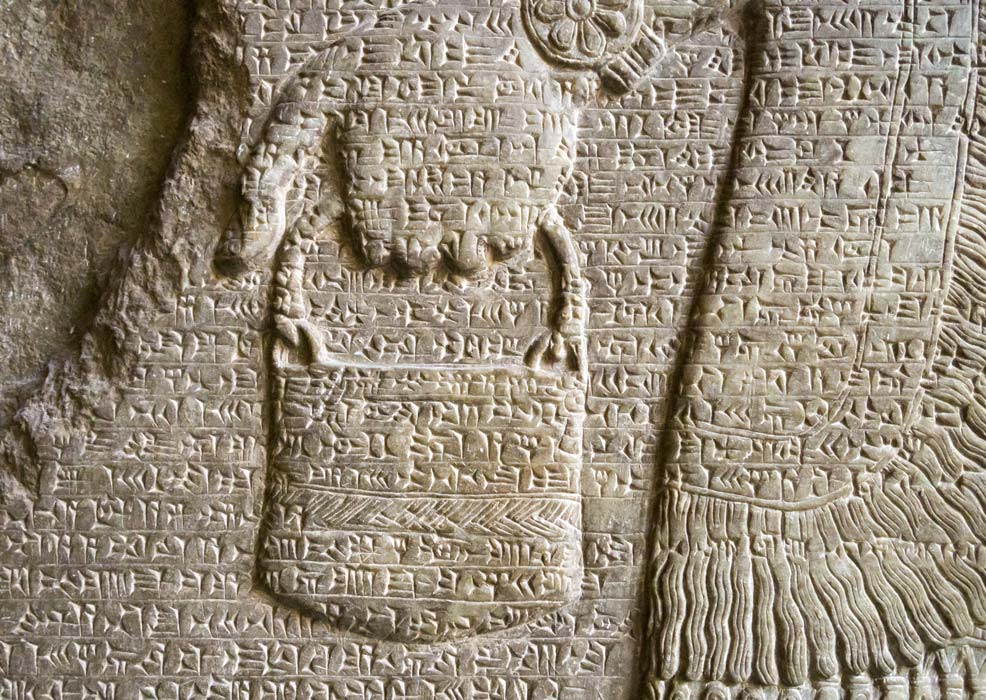

Once upon a time in the land of Mesopotamia, there lived a people who engaged in commerce, had a system of weights and measures, paid in currency, and most importantly, kept written records of all of this in clay tablets. These were the Sumerians.

1/51

Once upon a time in the land of Mesopotamia, there lived a people who engaged in commerce, had a system of weights and measures, paid in currency, and most importantly, kept written records of all of this in clay tablets. These were the Sumerians.

2/51

Writing was a real chore back then. The Sumerians would make tablets out of wet clay and use a hollow reed to etch circles and semi-circles into it while still wet and soft. Once done, the tablet would be baked in a kiln to make the etchings permanent. That's how they wrote.

Writing was a real chore back then. The Sumerians would make tablets out of wet clay and use a hollow reed to etch circles and semi-circles into it while still wet and soft. Once done, the tablet would be baked in a kiln to make the etchings permanent. That's how they wrote.

4/51

By around 2500 BC, the Akkadians entered the scene and drove the Sumerians out of Mesopotamia. What they didn't, however, is the cuneiform writing system. And the sexagesimal counting. By around 2000 BC, the system was mainstream all over Mesopotamia and Babylon.

By around 2500 BC, the Akkadians entered the scene and drove the Sumerians out of Mesopotamia. What they didn't, however, is the cuneiform writing system. And the sexagesimal counting. By around 2000 BC, the system was mainstream all over Mesopotamia and Babylon.

6/51

Also note that 60 looks identical to 1, both are represented by 𒁹. We'll come to that a little later. First, let's write a few numbers in cuneiform to better understand the system. It's all a combination of wedges (𒁹) and hooks (𒌋) in different permutations.

Also note that 60 looks identical to 1, both are represented by 𒁹. We'll come to that a little later. First, let's write a few numbers in cuneiform to better understand the system. It's all a combination of wedges (𒁹) and hooks (𒌋) in different permutations.

7/51

One last thing before we finally get down to writing numbers, don't let the symbols for 4-9 confuse you. They're just neatly arranged repetitions of 𒁹. So, 4 is actually 𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹 rendered as 𒐉 to save space. Similarly, 9 is 𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹 contracted to 𒑆.

One last thing before we finally get down to writing numbers, don't let the symbols for 4-9 confuse you. They're just neatly arranged repetitions of 𒁹. So, 4 is actually 𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹 rendered as 𒐉 to save space. Similarly, 9 is 𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹 contracted to 𒑆.

8/51

Let's start with the simplest number, 11. To the Sumerians, that'd be 10+1. 10 is 𒌋 and 1 is 𒁹, so 11 becomes 𒌋𒁹. Similarly, 15 would be 10+5, i.e. 𒌋𒐊. 20 becomes 10+10, i.e. 𒌋𒌋. 59 would be 10+10+10+10+10+9, or 𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋𒑆.

Easy, no? But things change after 59.

Let's start with the simplest number, 11. To the Sumerians, that'd be 10+1. 10 is 𒌋 and 1 is 𒁹, so 11 becomes 𒌋𒁹. Similarly, 15 would be 10+5, i.e. 𒌋𒐊. 20 becomes 10+10, i.e. 𒌋𒌋. 59 would be 10+10+10+10+10+9, or 𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋𒑆.

Easy, no? But things change after 59.

9/51

You see, from 1 thru 59, what we've done is count in 10s. Just like we do today. But the Sumerians, also counted in 60s. So they had a dedicated symbol for 60. It looked almost exactly like the symbol for 1, but significantly larger: 𒁹. So, 60 wasn't 𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋, but 𒁹.

You see, from 1 thru 59, what we've done is count in 10s. Just like we do today. But the Sumerians, also counted in 60s. So they had a dedicated symbol for 60. It looked almost exactly like the symbol for 1, but significantly larger: 𒁹. So, 60 wasn't 𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋𒌋, but 𒁹.

10/51

Again, the symbol for 60 looked similar to but was much larger than the symbol for 1. Since I cannot represent this size variation here, I will be representing 60 as 𒁹s wherever the context isn't clear. Hope that helps.

Now let's try writing a few more numbers.

Again, the symbol for 60 looked similar to but was much larger than the symbol for 1. Since I cannot represent this size variation here, I will be representing 60 as 𒁹s wherever the context isn't clear. Hope that helps.

Now let's try writing a few more numbers.

11/51

Take 63, for example. To the Sumerians, it'd be 60+3, i.e. 𒁹s𒁹𒁹𒁹. Just to reiterate, the first wedge here would be larger than the remaining three on an actual Mesopotamian tablet. 75, similarly, would be 60+10+5, i.e. 𒁹s𒌋𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹.

Take 63, for example. To the Sumerians, it'd be 60+3, i.e. 𒁹s𒁹𒁹𒁹. Just to reiterate, the first wedge here would be larger than the remaining three on an actual Mesopotamian tablet. 75, similarly, would be 60+10+5, i.e. 𒁹s𒌋𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹𒁹.

12/51

Finally, let's try a bigger number before moving on. How about 152? Let's see, we can break it down as 60+60+10+10+10+1+1 which gives us 𒁹s𒁹s𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹. On a real tablet, of course, it'd appear as 𒁹𒁹𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹 with the first two wedges much bigger than the last two.

Finally, let's try a bigger number before moving on. How about 152? Let's see, we can break it down as 60+60+10+10+10+1+1 which gives us 𒁹s𒁹s𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹. On a real tablet, of course, it'd appear as 𒁹𒁹𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹 with the first two wedges much bigger than the last two.

13/51

But this was problematic, the similarity of 𒁹s and 𒁹. Sizes could vary from hand to hand and a 62 (𒁹s𒁹𒁹) could very easily be misread, or even mis-etched, as 3 (𒁹𒁹𒁹)! This gave birth to the placeholder system. Someone decided to value a digit on where it sat.

But this was problematic, the similarity of 𒁹s and 𒁹. Sizes could vary from hand to hand and a 62 (𒁹s𒁹𒁹) could very easily be misread, or even mis-etched, as 3 (𒁹𒁹𒁹)! This gave birth to the placeholder system. Someone decided to value a digit on where it sat.

14/51

In our placeholder system, each positional shift to the left increases the value of the digit tenfold. We count as ones, tens, hundreds, and so on. The Sumerians counted as ones, 60s, 3,600s, and so on. Someone decided to make this a written standard.

In our placeholder system, each positional shift to the left increases the value of the digit tenfold. We count as ones, tens, hundreds, and so on. The Sumerians counted as ones, 60s, 3,600s, and so on. Someone decided to make this a written standard.

15/51

Now, the size of the wedge didn't matter. What mattered was its position. Thus, 𒁹 was 1 if in the ones (first) position, but 60 if in the sixties (second) position and 3,600 if in the third position. Just keep adding to the power of 60 as you move leftward.

Now, the size of the wedge didn't matter. What mattered was its position. Thus, 𒁹 was 1 if in the ones (first) position, but 60 if in the sixties (second) position and 3,600 if in the third position. Just keep adding to the power of 60 as you move leftward.

16/51

Thus, 152 could now be rendered as 60+60+10+10+10+1+1, i.e. 𒁹𒁹𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹. But there's still one problem. In English, each digit has a single symbol so it's easy to tell its position in a number. Not so in cuneiform. There's no way to tell the positions apart.

Thus, 152 could now be rendered as 60+60+10+10+10+1+1, i.e. 𒁹𒁹𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹. But there's still one problem. In English, each digit has a single symbol so it's easy to tell its position in a number. Not so in cuneiform. There's no way to tell the positions apart.

17/51

Take 𒁹𒁹𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹, for instance. Is this 2 positions or 7? If it's 2, where do they break? The solution was to group symbols of each position together with spaces between adjacent groups. Thus, 𒁹𒁹𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹 became 𒁹𒁹 𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹 for better clarity.

Take 𒁹𒁹𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹, for instance. Is this 2 positions or 7? If it's 2, where do they break? The solution was to group symbols of each position together with spaces between adjacent groups. Thus, 𒁹𒁹𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹 became 𒁹𒁹 𒌋𒌋𒌋𒁹𒁹 for better clarity.

18/51

This tiny update revolutionized counting. Now, very large numbers could be rendered with both ease and clarity. Take 1,275, for instance:

21 sixties + (10+5), i.e. 𒌋𒌋𒁹 𒌋𒐊.

This solved many problems, but not all. There are things positional counting didn't help with.

This tiny update revolutionized counting. Now, very large numbers could be rendered with both ease and clarity. Take 1,275, for instance:

21 sixties + (10+5), i.e. 𒌋𒌋𒁹 𒌋𒐊.

This solved many problems, but not all. There are things positional counting didn't help with.

19/51

Take 120 and 2. 120 is 𒁹𒁹 (2 sixties). 2 is also 𒁹𒁹 (2 ones). How do you tell the difference? One solution is to draw from the context which is what the Babylonians did for centuries. 𒁹𒁹 given as the population of a village is more likely to be 120 than 2.

Take 120 and 2. 120 is 𒁹𒁹 (2 sixties). 2 is also 𒁹𒁹 (2 ones). How do you tell the difference? One solution is to draw from the context which is what the Babylonians did for centuries. 𒁹𒁹 given as the population of a village is more likely to be 120 than 2.

21/51

So, while the blanks stayed as placeholder separator, the new symbol 𒑊 came to mean "nothing in this position." Thus, 𒁹 𒐊 was (1×60)+(5×1) = 65. But 𒁹 𒑊 𒐊 was (1×3,600)+(0×60)+(5×1) = 3,605.

Today, we use a different symbol for the job, we call it zero.

So, while the blanks stayed as placeholder separator, the new symbol 𒑊 came to mean "nothing in this position." Thus, 𒁹 𒐊 was (1×60)+(5×1) = 65. But 𒁹 𒑊 𒐊 was (1×3,600)+(0×60)+(5×1) = 3,605.

Today, we use a different symbol for the job, we call it zero.

22/51

This should've also resolved the 120-2 dilemma. While both 120 and 2 were rendered as two wedges each (larger for 120 and smaller for 2) earlier, now 2 could be 𒁹𒁹 (2 ones) and 120, 𒁹𒁹𒑊 (2 sixties plus zero ones).

But for some strange reason, this didn't happen.

This should've also resolved the 120-2 dilemma. While both 120 and 2 were rendered as two wedges each (larger for 120 and smaller for 2) earlier, now 2 could be 𒁹𒁹 (2 ones) and 120, 𒁹𒁹𒑊 (2 sixties plus zero ones).

But for some strange reason, this didn't happen.

23/51

That's because the Babylonians, despite having invented the gamechanger of a symbol, never used it at the end of a number. Why? We don't know. So, 2 was still 𒁹𒁹, as was 120, and the Babylonians still had to tell the two apart from context and nothing else.

That's because the Babylonians, despite having invented the gamechanger of a symbol, never used it at the end of a number. Why? We don't know. So, 2 was still 𒁹𒁹, as was 120, and the Babylonians still had to tell the two apart from context and nothing else.

24/51

This leap to a terminal zero-marker usage would take centuries. That being said, it's impossible to overstate the impact the Babylonian zero-marker, even in its non-terminal usage, had on their commerce in particular and life in general.

This leap to a terminal zero-marker usage would take centuries. That being said, it's impossible to overstate the impact the Babylonian zero-marker, even in its non-terminal usage, had on their commerce in particular and life in general.

25/51

One last thing before we leave Babylon: the zero-marker wasn't always 𒑊. Different scribes used different "standards." Bêl-bân-aplu, a 700 BC Babylonian, for instance, used 3 hooks (𒌋𒌋𒌋) to represent zero. I know, it looks like 30, but that's how he rolled.

One last thing before we leave Babylon: the zero-marker wasn't always 𒑊. Different scribes used different "standards." Bêl-bân-aplu, a 700 BC Babylonian, for instance, used 3 hooks (𒌋𒌋𒌋) to represent zero. I know, it looks like 30, but that's how he rolled.

26/51

So it's clear, the Babylonians were using some kind of a proto-zero, if you will, at least 3,000 years ago if not earlier still. Sure, it needed tons of refinement, but a zero it was. But were they the first in the world to have done it? Maybe, maybe not.

So it's clear, the Babylonians were using some kind of a proto-zero, if you will, at least 3,000 years ago if not earlier still. Sure, it needed tons of refinement, but a zero it was. But were they the first in the world to have done it? Maybe, maybe not.

27/51

Turns out, the Egyptians were doing their own thing with numbers much before the Babylonians, possibly even the Sumerians. Sure, they used hieroglyphs much of which remains undeciphered to this day, but their number system was surprisingly closer to what we have today.

Turns out, the Egyptians were doing their own thing with numbers much before the Babylonians, possibly even the Sumerians. Sure, they used hieroglyphs much of which remains undeciphered to this day, but their number system was surprisingly closer to what we have today.

28/51

For one, theirs was a base 10 system, just like ours. In contrast, the Sumerians were base 60. We still use base 60, by the way, in certain niches which is why we have 60 seconds to a minute and 60 minutes to an hour. But base 10 is pretty much the mainstream.

For one, theirs was a base 10 system, just like ours. In contrast, the Sumerians were base 60. We still use base 60, by the way, in certain niches which is why we have 60 seconds to a minute and 60 minutes to an hour. But base 10 is pretty much the mainstream.

31/51

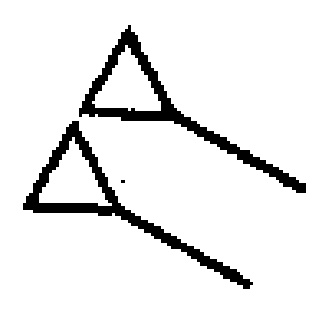

Between the Egyptians and the Babylonians, it's hard to tell who came up with the zero-marker, however rudimentary, first. That said, most evidences available point to the Egyptians. Nfr can be seen as human civilization's first attempt at denoting "nothing."

Between the Egyptians and the Babylonians, it's hard to tell who came up with the zero-marker, however rudimentary, first. That said, most evidences available point to the Egyptians. Nfr can be seen as human civilization's first attempt at denoting "nothing."

35/51

Coming back to the Old World, the first Europeans with some kind of number system were the Greeks. They had a positional lettering system in base 10, sometimes also 5, which is what the Romans would borrow later. But the Greeks has no zero, at least not until Alexander.

Coming back to the Old World, the first Europeans with some kind of number system were the Greeks. They had a positional lettering system in base 10, sometimes also 5, which is what the Romans would borrow later. But the Greeks has no zero, at least not until Alexander.

37/51

But the Greeks wrote zero the way we do today: as a circle. There's several theories around how two tiled wedges of Babylon turned into the Greek circle. The most widely accepted is that the circle is omicron. It's the first letter of οὐδέν, Greek for nothing.

But the Greeks wrote zero the way we do today: as a circle. There's several theories around how two tiled wedges of Babylon turned into the Greek circle. The most widely accepted is that the circle is omicron. It's the first letter of οὐδέν, Greek for nothing.

38/51

The first time zero makes an appearance in Asia is at the most generous least 100 years after the Greeks started with the circle notation. In fact, it can all be narrowed down to one individual.

Pingala.

You probably expected the name Āryabhatta, but that's much later.

The first time zero makes an appearance in Asia is at the most generous least 100 years after the Greeks started with the circle notation. In fact, it can all be narrowed down to one individual.

Pingala.

You probably expected the name Āryabhatta, but that's much later.

39/51

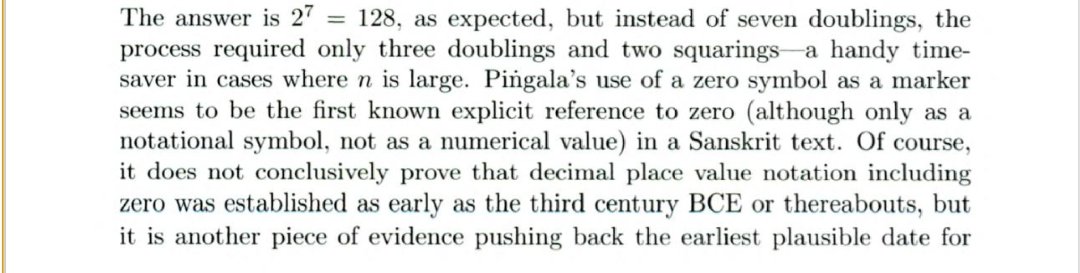

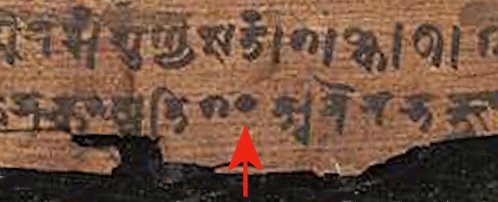

Pingala is said to have come up with a primitive form of the binary system in his 200 BC work Chandaḥśāstra. This is the text that introduces us to śūnya, a dot notation that's understood to represent nothingness. As a notation, this is the first Asian zero.

Pingala is said to have come up with a primitive form of the binary system in his 200 BC work Chandaḥśāstra. This is the text that introduces us to śūnya, a dot notation that's understood to represent nothingness. As a notation, this is the first Asian zero.

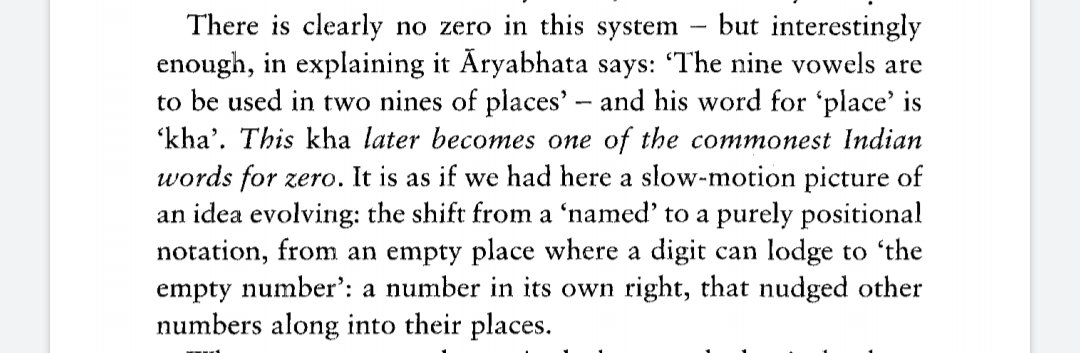

43/51

Āryabhatta's kha (his name for zero) and Pingala's śūnya were both mere symbolic. They served no numerical functions although they did aid calculations, just as placeholder variables aid calculations today.

Āryabhatta's kha (his name for zero) and Pingala's śūnya were both mere symbolic. They served no numerical functions although they did aid calculations, just as placeholder variables aid calculations today.

44/51

Of course there's also debate on whether Āryabhatta even existed and if he did, whether as one individual or many. But that's a debate we won't get into here and just work with the assumption that he existed and as a single individual.

Of course there's also debate on whether Āryabhatta even existed and if he did, whether as one individual or many. But that's a debate we won't get into here and just work with the assumption that he existed and as a single individual.

45/51

About half a century after Āryabhatta, comes Varāhamihira of Ujjain. He, like his predecessors, didn't have a zero in any numerical sense but he gave it a new name, ākāśa. The word is also Sanskrit for sky. Do now we have śūnya, kha, and ākāśa — all mere notational.

About half a century after Āryabhatta, comes Varāhamihira of Ujjain. He, like his predecessors, didn't have a zero in any numerical sense but he gave it a new name, ākāśa. The word is also Sanskrit for sky. Do now we have śūnya, kha, and ākāśa — all mere notational.

47/51

In 662 AD, this Syrian fan of Indian arithmetic wrote about how the Indians expressed numbers using nine symbols.

Nine, not ten.

That's one of the most compelling arguments against the Indian zero as a marker of numerical significance.

tertullian.org

In 662 AD, this Syrian fan of Indian arithmetic wrote about how the Indians expressed numbers using nine symbols.

Nine, not ten.

That's one of the most compelling arguments against the Indian zero as a marker of numerical significance.

tertullian.org

48/51

So who gets to own zero exactly?

The Babylonians who invented the idea of expressing numerically significant nothingness with two slanting wedges around 3,000 years ago?

The Egyptians who repurposed nfr, the hieroglyph for beautiful, to denote nothingness?

So who gets to own zero exactly?

The Babylonians who invented the idea of expressing numerically significant nothingness with two slanting wedges around 3,000 years ago?

The Egyptians who repurposed nfr, the hieroglyph for beautiful, to denote nothingness?

49/51

The Mayans who first wrote it as an oval?

The Greeks who first wrote it as a circle?

The Indians who first wrote it as a dot but with no numerical significance?

Truth is, it belongs to all. Mathematics, like sciences, is a trans-civilizational endeavor.

The Mayans who first wrote it as an oval?

The Greeks who first wrote it as a circle?

The Indians who first wrote it as a dot but with no numerical significance?

Truth is, it belongs to all. Mathematics, like sciences, is a trans-civilizational endeavor.

50/51

No one civilization can claim monopoly over something as broad as zero. Different improvisations emerged in different parts of the world as and when the needs were felt. There's little value, then, in romanticing a fictitious antiquity where one culture owns it all.

No one civilization can claim monopoly over something as broad as zero. Different improvisations emerged in different parts of the world as and when the needs were felt. There's little value, then, in romanticing a fictitious antiquity where one culture owns it all.

51/51

Funnily enough, as if to close the loop, this zero that India inherited from Pingala, made its way back into Europe as part of the Hindu-Arabic system in the 11th century thanks to the Moors of Andalusia who were voracious translators.

That's how zero came to be.

Funnily enough, as if to close the loop, this zero that India inherited from Pingala, made its way back into Europe as part of the Hindu-Arabic system in the 11th century thanks to the Moors of Andalusia who were voracious translators.

That's how zero came to be.

Loading suggestions...