3/

Here's the poll question I asked:

Suppose we have a stock that multiplies in value by a factor of N.

But it takes N years to do so.

What's the *maximum* rate of return (CAGR) that we can get from such a stock -- assuming we are free to choose whatever N we like?

Here's the poll question I asked:

Suppose we have a stock that multiplies in value by a factor of N.

But it takes N years to do so.

What's the *maximum* rate of return (CAGR) that we can get from such a stock -- assuming we are free to choose whatever N we like?

5/

So, let's work out the solution to this problem.

And then we'll discuss broader implications for investors.

👇👇👇

So, let's work out the solution to this problem.

And then we'll discuss broader implications for investors.

👇👇👇

6/

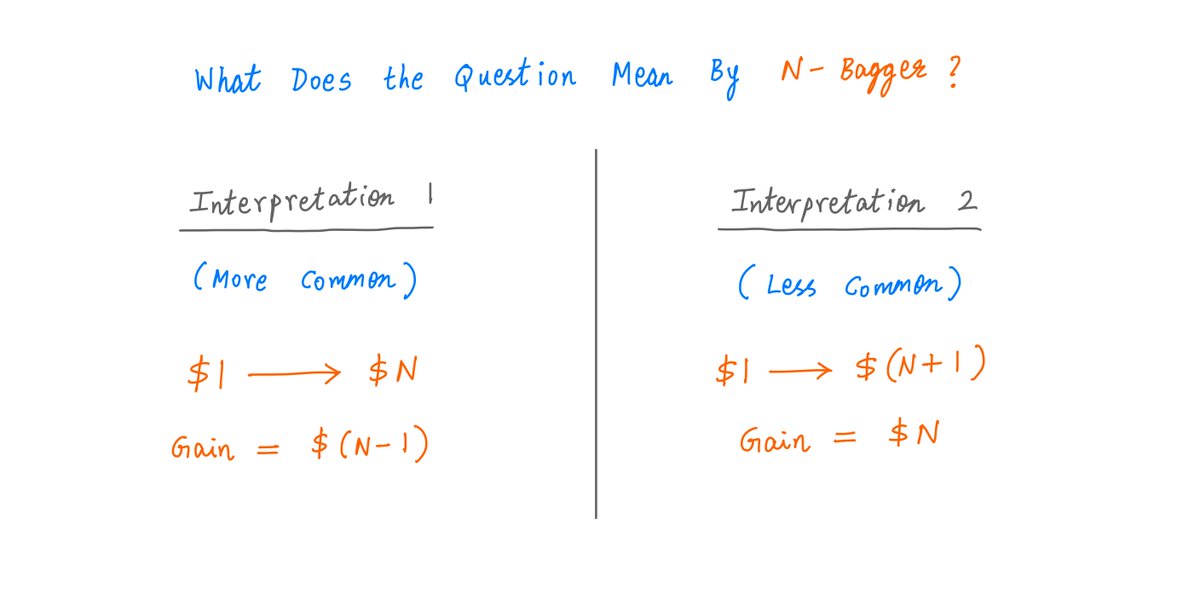

First, we should clarify a potential ambiguity in the phrasing of the question.

The question uses the phrase "N-bagger" to mean "a stock that grows in value by a factor of N".

But there are 2 ways to interpret this.

First, we should clarify a potential ambiguity in the phrasing of the question.

The question uses the phrase "N-bagger" to mean "a stock that grows in value by a factor of N".

But there are 2 ways to interpret this.

13/

A more sophisticated way to solve the problem is via Differential Calculus.

This has 2 advantages over "plotting and zooming":

a) We don't need a computer. We can work out the answer using just pen and paper. And,

b) We get an *exact* answer -- not just an approximation.

A more sophisticated way to solve the problem is via Differential Calculus.

This has 2 advantages over "plotting and zooming":

a) We don't need a computer. We can work out the answer using just pen and paper. And,

b) We get an *exact* answer -- not just an approximation.

14/

The central idea in Differential Calculus is the *derivative* -- a measure of how *quickly* a function changes when its inputs change.

Here, we have CAGR as a function of N.

So, the "derivative" of this function measures how quickly CAGR changes when we change N.

The central idea in Differential Calculus is the *derivative* -- a measure of how *quickly* a function changes when its inputs change.

Here, we have CAGR as a function of N.

So, the "derivative" of this function measures how quickly CAGR changes when we change N.

17/

We want to find the point where CAGR is at its *maximum*.

That is: *upto* this point, CAGR *increases* with N. But *after* this point, CAGR *decreases* with N.

And that means: we're looking for the point where our orange curve *transitions* from POSITIVE to NEGATIVE.

We want to find the point where CAGR is at its *maximum*.

That is: *upto* this point, CAGR *increases* with N. But *after* this point, CAGR *decreases* with N.

And that means: we're looking for the point where our orange curve *transitions* from POSITIVE to NEGATIVE.

19/

So, calculus is telling us that we'll find our maximum CAGR at N = e = ~2.718...

This, of course, matches the approximation we found via "plot and zoom".

e is a fundamental and fascinating math quantity. It pops up in all kinds of places.

For more:

So, calculus is telling us that we'll find our maximum CAGR at N = e = ~2.718...

This, of course, matches the approximation we found via "plot and zoom".

e is a fundamental and fascinating math quantity. It pops up in all kinds of places.

For more:

20/

Our poll question also carries broader investing implications.

For example, one immediate conclusion is that we can't just focus on how many "multiples" we bag.

The *time* it takes to bag said multiple is crucial.

Our poll question also carries broader investing implications.

For example, one immediate conclusion is that we can't just focus on how many "multiples" we bag.

The *time* it takes to bag said multiple is crucial.

21/

I see lots of discussions on FinTwit about 10 baggers, 100 baggers, etc.

But very few of these discussions incorporate the *time* factor.

Even a 100 bagger is NOT particularly wonderful -- if it takes 100 years to work its magic. As we've seen, that's only a ~4.71% CAGR.

I see lots of discussions on FinTwit about 10 baggers, 100 baggers, etc.

But very few of these discussions incorporate the *time* factor.

Even a 100 bagger is NOT particularly wonderful -- if it takes 100 years to work its magic. As we've seen, that's only a ~4.71% CAGR.

22/

But on the other hand, we also shouldn't focus on JUST maximizing CAGR/IRR -- to the exclusion of everything else.

A key question to ask is: *how long* can we sustain a particular CAGR/IRR?

But on the other hand, we also shouldn't focus on JUST maximizing CAGR/IRR -- to the exclusion of everything else.

A key question to ask is: *how long* can we sustain a particular CAGR/IRR?

23/

For example, suppose we buy a stock and it goes up 2% in one day.

That's a whopping (1.02^365 - 1)*100 = ~137,641% CAGR!

But is it sustainable? Can we grow our portfolio at 2% per day every single day? Most likely not.

For example, suppose we buy a stock and it goes up 2% in one day.

That's a whopping (1.02^365 - 1)*100 = ~137,641% CAGR!

But is it sustainable? Can we grow our portfolio at 2% per day every single day? Most likely not.

24/

Over short time durations, CAGRs/IRRs can be very misleading.

For most of us, a *decent* CAGR that can be sustained for *decades* will leave us better off than a *great* CAGR that quickly peters out.

We should direct our search for investment opportunities accordingly.

Over short time durations, CAGRs/IRRs can be very misleading.

For most of us, a *decent* CAGR that can be sustained for *decades* will leave us better off than a *great* CAGR that quickly peters out.

We should direct our search for investment opportunities accordingly.

25/

A closely related concern is "re-investment risk".

For example, Business #1 may be able to invest capital at a 50% IRR.

But only for a limited amount of time -- until the market gets saturated or competition steps up or whatever.

A closely related concern is "re-investment risk".

For example, Business #1 may be able to invest capital at a 50% IRR.

But only for a limited amount of time -- until the market gets saturated or competition steps up or whatever.

26/

This business has re-investment risk. It's unlikely that management will be able to keep re-investing profits for long at 50%.

By contrast, Business #2 may get an IRR of only 20%. But they may have a "moat" that lets them keep re-investing profits for decades at that rate.

This business has re-investment risk. It's unlikely that management will be able to keep re-investing profits for long at 50%.

By contrast, Business #2 may get an IRR of only 20%. But they may have a "moat" that lets them keep re-investing profits for decades at that rate.

27/

There's yet another factor: the amount of capital that can be deployed.

Businesses like Berkshire, for example, have tens of billions of dollars to invest.

An opportunity that lets them invest, say, $50M at a 200% IRR, still doesn't move the needle very much.

There's yet another factor: the amount of capital that can be deployed.

Businesses like Berkshire, for example, have tens of billions of dollars to invest.

An opportunity that lets them invest, say, $50M at a 200% IRR, still doesn't move the needle very much.

28/

By contrast, an opportunity that lets them earn only 10% to 12% IRR can still be very attractive -- IF it can absorb tens of billions of dollars every year.

Again, the goal isn't just to maximize IRR. It's to maximize end net worth/utility -- adjusted for risk.

By contrast, an opportunity that lets them earn only 10% to 12% IRR can still be very attractive -- IF it can absorb tens of billions of dollars every year.

Again, the goal isn't just to maximize IRR. It's to maximize end net worth/utility -- adjusted for risk.

29/

Thus, while choosing an investment for our portfolio, we should consider a bunch of factors:

- the IRR we'll get,

- how long this IRR will be sustained for,

- re-investment risk,

- how much capital can be deployed,

- the uncertainty around the IRR and its duration, etc.

Thus, while choosing an investment for our portfolio, we should consider a bunch of factors:

- the IRR we'll get,

- how long this IRR will be sustained for,

- re-investment risk,

- how much capital can be deployed,

- the uncertainty around the IRR and its duration, etc.

30/

Howard Marks (@HowardMarksBook) has written a wonderful memo dissecting some of these factors.

It has the lovely title: You Can't Eat IRR.

Link: oaktreecapital.com

Howard Marks (@HowardMarksBook) has written a wonderful memo dissecting some of these factors.

It has the lovely title: You Can't Eat IRR.

Link: oaktreecapital.com

31/

I'd also like to thank Ho Nam (@honam) for his perspectives on why many fund managers are incentivized to maximize IRR, and Prof. Sanjay Bakshi (@Sanjay__Bakshi) for his keen insights about re-investment risk.

I'd also like to thank Ho Nam (@honam) for his perspectives on why many fund managers are incentivized to maximize IRR, and Prof. Sanjay Bakshi (@Sanjay__Bakshi) for his keen insights about re-investment risk.

32/

And if you want to learn more about the history of calculus and all the wonderful things it lets us do, here's an outstanding non-technical book by Prof. Steven Strogatz (@stevenstrogatz): Infinite Powers.

amazon.com

And if you want to learn more about the history of calculus and all the wonderful things it lets us do, here's an outstanding non-technical book by Prof. Steven Strogatz (@stevenstrogatz): Infinite Powers.

amazon.com

34/

Thank you very much for taking the time to read all the way to the end.

Please stay safe. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

Thank you very much for taking the time to read all the way to the end.

Please stay safe. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

Loading suggestions...