4/50

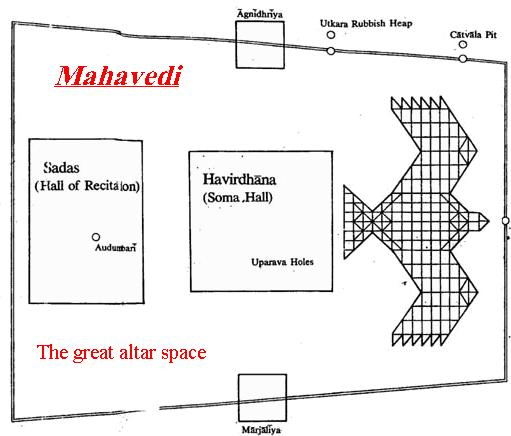

The works deal with mensuration and construction of the various altars or arenas for religious rites. These measurements, back in the day, were done using pieces of strings or śulbas, hence the name.

Do note that all math here was applied geometry.

The works deal with mensuration and construction of the various altars or arenas for religious rites. These measurements, back in the day, were done using pieces of strings or śulbas, hence the name.

Do note that all math here was applied geometry.

5/50

When the Śulbasūtras emerged, we’ll get to in a bit. First, let’s understand what they say about the theorem in question and how.

As I said, there’s eight books.

Among them is one by Baudhāyana—the Baudhāyana Śulba Sūtras, BSS from here on. This is our book of interest.

When the Śulbasūtras emerged, we’ll get to in a bit. First, let’s understand what they say about the theorem in question and how.

As I said, there’s eight books.

Among them is one by Baudhāyana—the Baudhāyana Śulba Sūtras, BSS from here on. This is our book of interest.

7/50

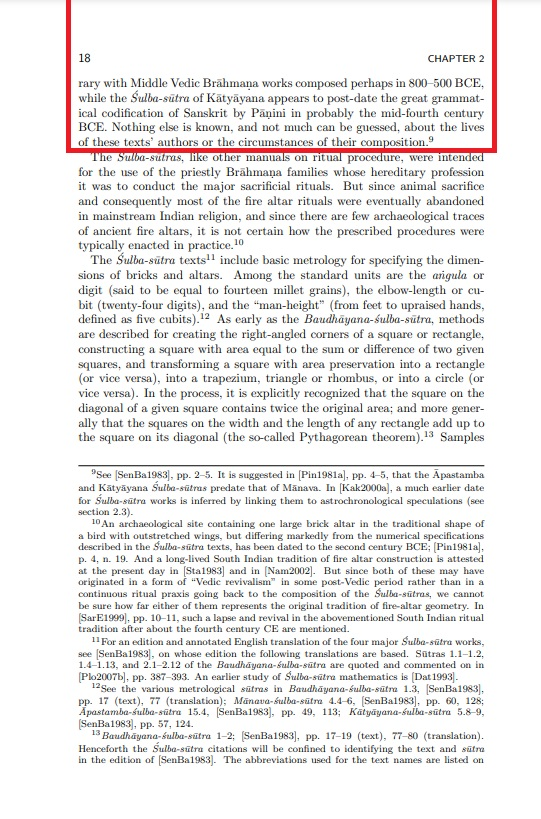

The design and dimensions of the mahāvedi have also been addressed in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa, an older Vedic commentary, but it’s only in the Baudhāyana text that the idea has been expounded in detail. The Brāhmaṇa’s geometry is extremely cursory.

The design and dimensions of the mahāvedi have also been addressed in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa, an older Vedic commentary, but it’s only in the Baudhāyana text that the idea has been expounded in detail. The Brāhmaṇa’s geometry is extremely cursory.

8/50

So whenever they say Vedic math, they essentially mean geometry and associated algebra as discussed in the BSS corpus, even if unknowingly so.

With that bit out of the way, let’s zoom in to the exact verse.

So whenever they say Vedic math, they essentially mean geometry and associated algebra as discussed in the BSS corpus, even if unknowingly so.

With that bit out of the way, let’s zoom in to the exact verse.

9/50

Do note that Baudhāyana did many kinds of sūtras, including Śulba and Śrauta. Our verse shows up in the former. This distinction is important because the free copies available online are almost always of the Śrauta text and not Śulba.

Now the verse…

Do note that Baudhāyana did many kinds of sūtras, including Śulba and Śrauta. Our verse shows up in the former. This distinction is important because the free copies available online are almost always of the Śrauta text and not Śulba.

Now the verse…

10/50

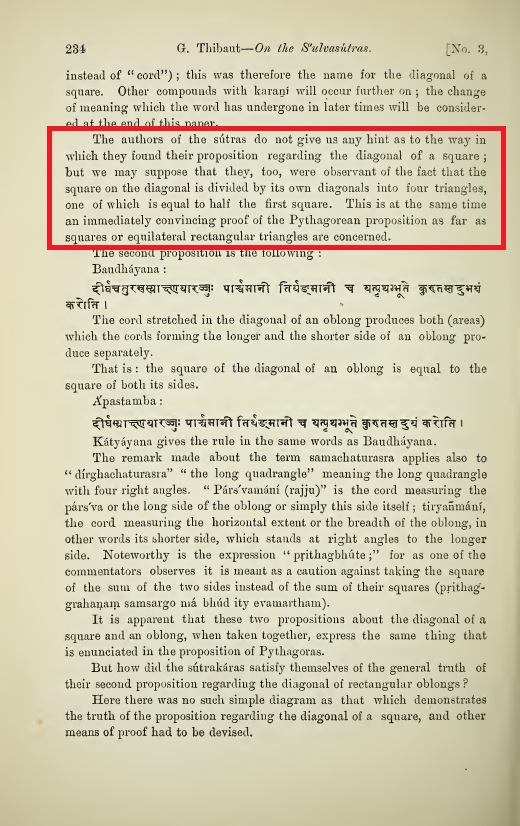

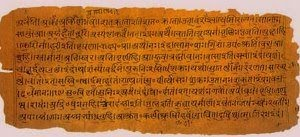

Original (verse 1.12):

दीर्घचतुरश्रस्याक्ष्णया रज्जुः पार्श्वमानी तिर्यग् मानी च यत् पृथग् भूते कुरूतस्तदुभयं करोति॥

Transliteration:

dīrghachatursrasyākṣaṇayā rajjuḥ pārśvamānī, tiryagmānī,

cha yatpṛthagbhūte kurutastadubhayāṅ karoti.

Original (verse 1.12):

दीर्घचतुरश्रस्याक्ष्णया रज्जुः पार्श्वमानी तिर्यग् मानी च यत् पृथग् भूते कुरूतस्तदुभयं करोति॥

Transliteration:

dīrghachatursrasyākṣaṇayā rajjuḥ pārśvamānī, tiryagmānī,

cha yatpṛthagbhūte kurutastadubhayāṅ karoti.

13/50

The rule is further illustrated with examples in 1.13 that reads thus:

tāsāṃ trika-catuskayār-dvādaśika-pañcikayāḥ pañca-daśikāṣṭikāyāḥ saptaka-catu-viṃśikayār-dvādaśika-pañcātriṃśikayāḥ pañca-daśikāṣṭi-triśikayārityāsu-upaladhāḥ.

The rule is further illustrated with examples in 1.13 that reads thus:

tāsāṃ trika-catuskayār-dvādaśika-pañcikayāḥ pañca-daśikāṣṭikāyāḥ saptaka-catu-viṃśikayār-dvādaśika-pañcātriṃśikayāḥ pañca-daśikāṣṭi-triśikayārityāsu-upaladhāḥ.

14/50

This verse basically lists out a bunch of values for which the rule had been found to hold. These include 3 and 4; 12 and 5; 15 and 8; 7 and 24; 12 and 35; and 15 and 36.

Evidently, only these values mattered in the relevant context, i.e. altar dimensions.

This verse basically lists out a bunch of values for which the rule had been found to hold. These include 3 and 4; 12 and 5; 15 and 8; 7 and 24; 12 and 35; and 15 and 36.

Evidently, only these values mattered in the relevant context, i.e. altar dimensions.

16/50

Naturally, this worked for them. Artisans and priests had no need for other dimensions, so they stuck to the ones given in the sūtra rather than resolving it for other values. In other words, it was all applied geometry with no need for theoretical proofs.

Naturally, this worked for them. Artisans and priests had no need for other dimensions, so they stuck to the ones given in the sūtra rather than resolving it for other values. In other words, it was all applied geometry with no need for theoretical proofs.

17/50

Pythagoras’, on the other hand, was a more comprehensive theorem and covered all pairs. That’s because being theoretical, his theorem also came with detailed step-by-step proof of derivation which could subsequently be resolved for any arbitrary triangle.

Pythagoras’, on the other hand, was a more comprehensive theorem and covered all pairs. That’s because being theoretical, his theorem also came with detailed step-by-step proof of derivation which could subsequently be resolved for any arbitrary triangle.

18/50

And that’s why some may feel it’s only fair that Pythagoras get his name on the equation.

Kind of like the airplane. We know Da Vinci drew the concept centuries before the Wrights, but it’s still the latter that got the credit for showing how it actually works.

And that’s why some may feel it’s only fair that Pythagoras get his name on the equation.

Kind of like the airplane. We know Da Vinci drew the concept centuries before the Wrights, but it’s still the latter that got the credit for showing how it actually works.

19/50

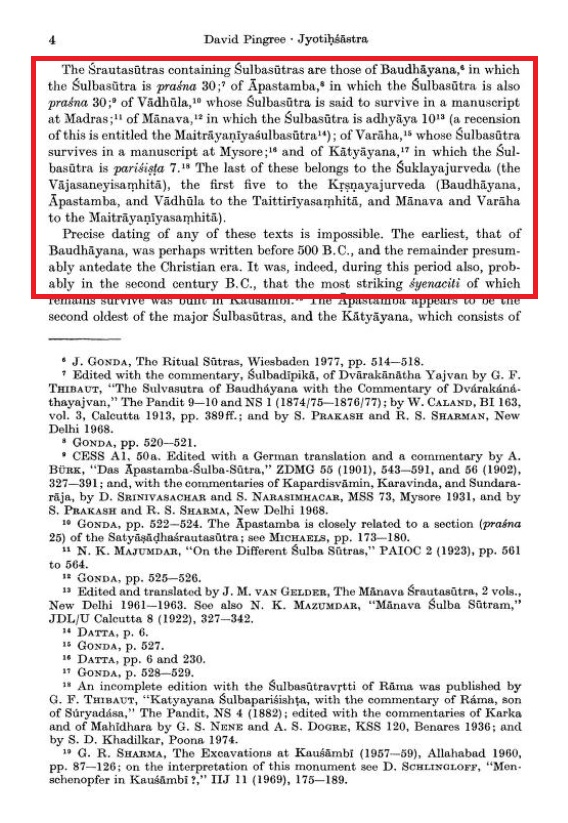

Now chronology-wise, there’s no doubt the BSS beat Pythagoras by centuries. While Pythagoras was born in the 5th century BC, the BSS dates back to at least three centuries earlier.

And that brings us to the age of BSS.

As of now, the consensus stands on 9th century BC.

Now chronology-wise, there’s no doubt the BSS beat Pythagoras by centuries. While Pythagoras was born in the 5th century BC, the BSS dates back to at least three centuries earlier.

And that brings us to the age of BSS.

As of now, the consensus stands on 9th century BC.

24/50

Albeit still largely arbitrary, 800 BC seems to enjoy widespread currency amongst scholars both in and outside of India. In the absence of any conclusive evidence to the contrary, I’m sticking to this date for this conversation.

Albeit still largely arbitrary, 800 BC seems to enjoy widespread currency amongst scholars both in and outside of India. In the absence of any conclusive evidence to the contrary, I’m sticking to this date for this conversation.

25/50

So that makes BSS at least 300 years older than Pythagoras. Even if we go by Pingree’s 500 BC, the two only come nearly contemporary at best.

Who gets the credit in that case?

Well, I said “nearly” contemporary because Pythagoras was still 70 years before 500 BC.

So that makes BSS at least 300 years older than Pythagoras. Even if we go by Pingree’s 500 BC, the two only come nearly contemporary at best.

Who gets the credit in that case?

Well, I said “nearly” contemporary because Pythagoras was still 70 years before 500 BC.

26/50

Now, do note that the two cultures hadn’t yet come in contact yet; that wouldn’t happen until around Alexander.

So even if contemporary, there’s no way either would’ve borrowed from the other. This establishes the purely indigenous origins of BSS.

And also Pythagoras.

Now, do note that the two cultures hadn’t yet come in contact yet; that wouldn’t happen until around Alexander.

So even if contemporary, there’s no way either would’ve borrowed from the other. This establishes the purely indigenous origins of BSS.

And also Pythagoras.

27/50

One may debate the assignment of credit in this close call, especially when it’s certain both discoveries were independent of each other, the story isn’t over yet.

But before we get there, let’s introduce the term Pythagorean triplets. This will feature a lot now.

One may debate the assignment of credit in this close call, especially when it’s certain both discoveries were independent of each other, the story isn’t over yet.

But before we get there, let’s introduce the term Pythagorean triplets. This will feature a lot now.

28/50

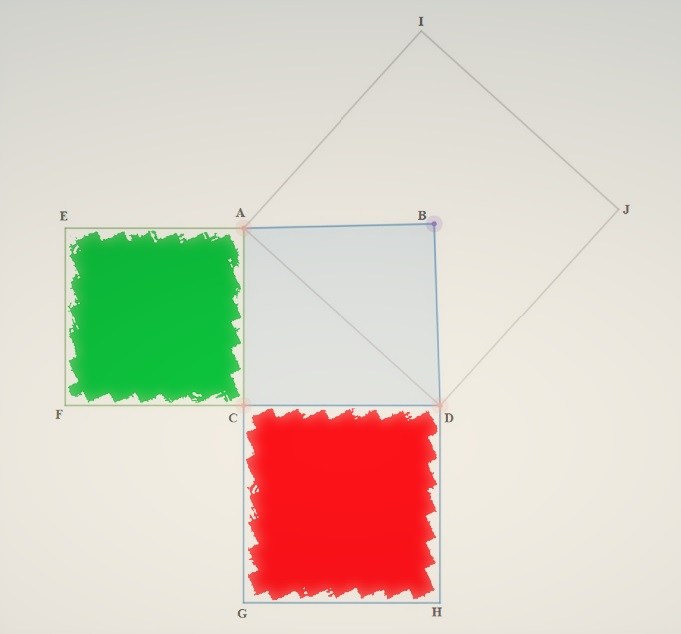

A Pythagorean triple, or just triple, is any set of three whole numbers that satisfy the theorem a² + b² = c². Here, a, b, and c are, of course, the three sides of a right-angle triangle, c being the hypotenuse.

Take, for instance, the set of 3, 4, and 5:

3² + 4² = 5².

A Pythagorean triple, or just triple, is any set of three whole numbers that satisfy the theorem a² + b² = c². Here, a, b, and c are, of course, the three sides of a right-angle triangle, c being the hypotenuse.

Take, for instance, the set of 3, 4, and 5:

3² + 4² = 5².

31/50

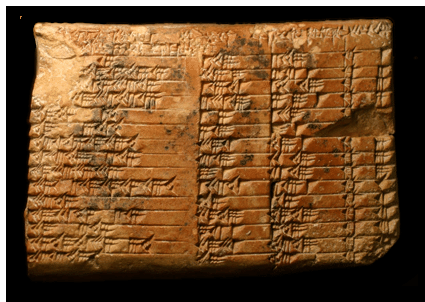

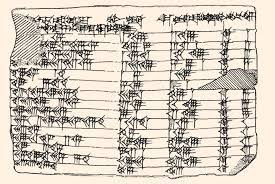

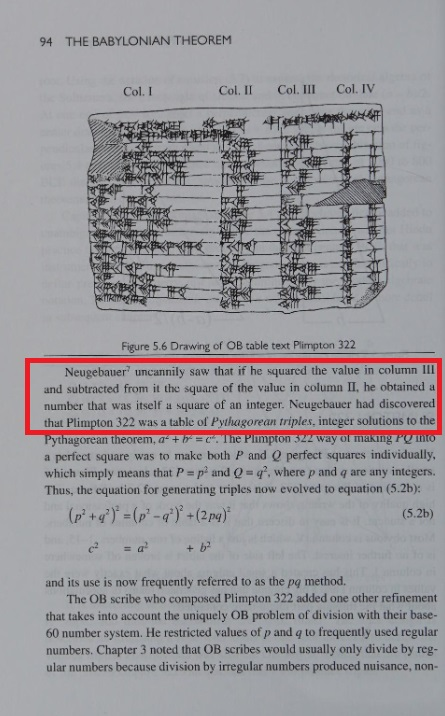

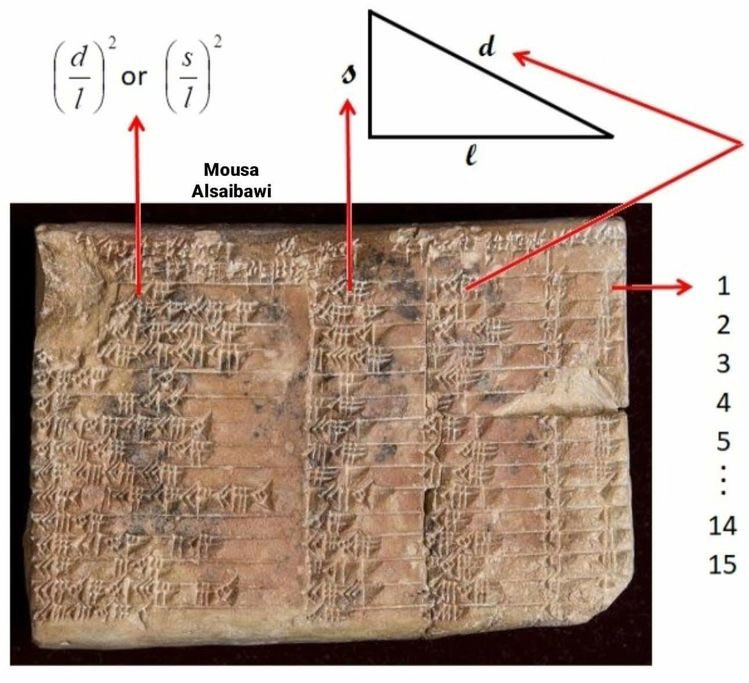

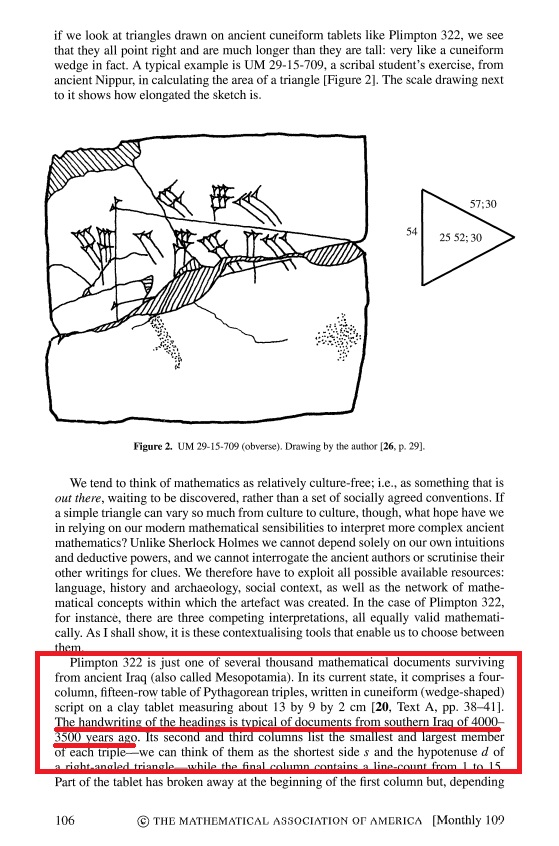

What makes this artifact of interest to this conversation is its contents. Largely intact, save a couple of small chips on the upper left and mid-right, the piece is inscribed with a “spreadsheet” of 16 rows and 4 columns, filled with numerals in Old Babylonian cuneiform.

What makes this artifact of interest to this conversation is its contents. Largely intact, save a couple of small chips on the upper left and mid-right, the piece is inscribed with a “spreadsheet” of 16 rows and 4 columns, filled with numerals in Old Babylonian cuneiform.

33/50

Neugebauer concluded the first row to be a header row and the last column to be a header column with serial numbers, much like a modern Excel sheet done right-to-left (do note that the Mesopotamians wrote right to left).

Neugebauer concluded the first row to be a header row and the last column to be a header column with serial numbers, much like a modern Excel sheet done right-to-left (do note that the Mesopotamians wrote right to left).

34/50

To understand his observations, let’s number the columns. Since the writing system is right-to-left, the 4th column is technically the “first.” But since it’s just serial numbers, we’ll ignore it. That leaves us with three columns, first thru third, right to left.

To understand his observations, let’s number the columns. Since the writing system is right-to-left, the 4th column is technically the “first.” But since it’s just serial numbers, we’ll ignore it. That leaves us with three columns, first thru third, right to left.

37/50

Just like Baudhāyana, the Mesopotamians offer no proof of deduction. All they give is a set of arbitrary values that fit the rule, which is understandable given their preoccupation with practical application rather than theoretical inquiry.

Just like Baudhāyana, the Mesopotamians offer no proof of deduction. All they give is a set of arbitrary values that fit the rule, which is understandable given their preoccupation with practical application rather than theoretical inquiry.

38/50

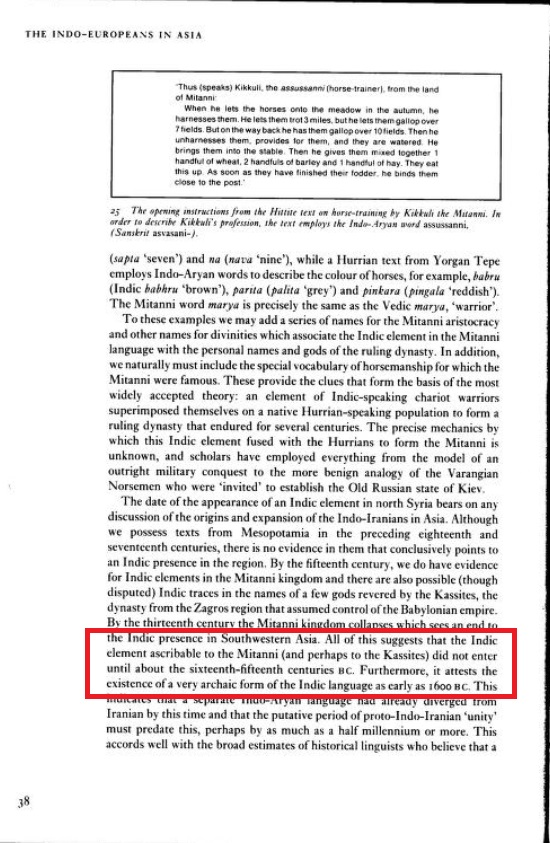

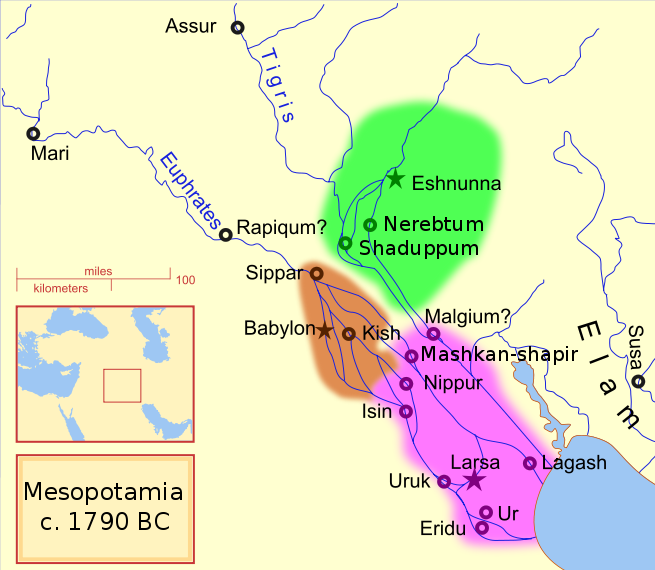

Of course, it’s extremely unlikely that Baudhāyana borrowed knowledge from the Mesopotamians although the exchange between the two civilizations goes back to the IVC times.

But one came before the other. And must one force a credit, it ought to go to that one.

Of course, it’s extremely unlikely that Baudhāyana borrowed knowledge from the Mesopotamians although the exchange between the two civilizations goes back to the IVC times.

But one came before the other. And must one force a credit, it ought to go to that one.

40/50

Things still don’t stop here.

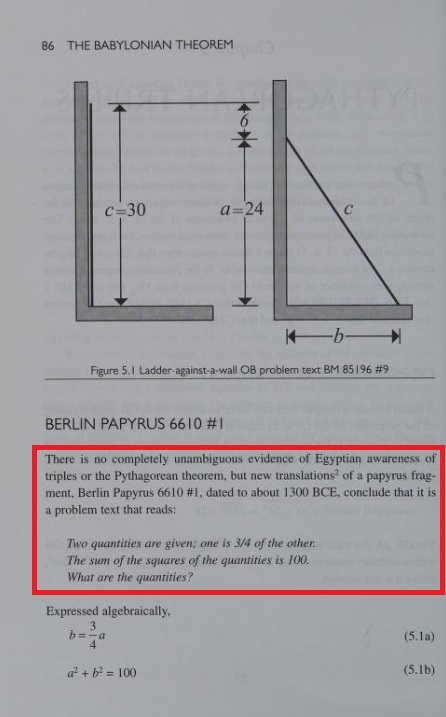

Enter the Berlin Papyrus, more accurately Berlin Papyrus 6619.

Albeit the tablet remains the oldest expression of Pythagoras’ rule, the papyrus, too, beats Baudhāyana by a good half millennium, if not more.

Things still don’t stop here.

Enter the Berlin Papyrus, more accurately Berlin Papyrus 6619.

Albeit the tablet remains the oldest expression of Pythagoras’ rule, the papyrus, too, beats Baudhāyana by a good half millennium, if not more.

42/50

The problem roughly translates thus:

“There are two numbers.

One is three-fourths of the other.

The squares of both add up to 100.

What are the numbers?”

In algebraic terms:

b = 3a/4, and

a² + b² = 100

The problem roughly translates thus:

“There are two numbers.

One is three-fourths of the other.

The squares of both add up to 100.

What are the numbers?”

In algebraic terms:

b = 3a/4, and

a² + b² = 100

43/50

Anyone who took math in high school should be able to solve the equations as follows:

a² + (3a/4)² = 100

or, a² + a²(3/4)² = 100

or, a²(1 + 9/16) = 100

or, 25a²/16 = 100

or, (5a/4)² = 10²

or, a = 8

subsequently, b = 6.

Only one problem, the Egyptians didn’t know this.

Anyone who took math in high school should be able to solve the equations as follows:

a² + (3a/4)² = 100

or, a² + a²(3/4)² = 100

or, a²(1 + 9/16) = 100

or, 25a²/16 = 100

or, (5a/4)² = 10²

or, a = 8

subsequently, b = 6.

Only one problem, the Egyptians didn’t know this.

44/50

So how did they solve the problem if not algebraically?

They did it geometrically. The method is called “false proposition.” I will spare you the boring mathematical details but remember, the Egyptians had been doing right-angle triangles since at least 2600 BC.

So how did they solve the problem if not algebraically?

They did it geometrically. The method is called “false proposition.” I will spare you the boring mathematical details but remember, the Egyptians had been doing right-angle triangles since at least 2600 BC.

45/50

But the Egyptian side has only this papyrus fragment to bolster its claim. And the pyramids, of course. The problem discussed above suggests at least one Pythagorean triple, i.e. 6, 8, 10.

But it does.

Again, we don’t know for sure if they borrowed from the Babylonians.

But the Egyptian side has only this papyrus fragment to bolster its claim. And the pyramids, of course. The problem discussed above suggests at least one Pythagorean triple, i.e. 6, 8, 10.

But it does.

Again, we don’t know for sure if they borrowed from the Babylonians.

46/50

But the Babylonians and the Egyptians did make contacts. And so did the Indians and the Babylonians. A transfer of knowledge while not established cannot be completely ruled out.

Setting aside the contentious transfer bit, the Babylonians still predate the Indians.

But the Babylonians and the Egyptians did make contacts. And so did the Indians and the Babylonians. A transfer of knowledge while not established cannot be completely ruled out.

Setting aside the contentious transfer bit, the Babylonians still predate the Indians.

48/50

Now the question is, who gets the credit?

And on what qualification?

If it’s vintage, the Egyptians win hands down.

If it’s thoroughness, the Greeks get it.

And that’s assuming everybody came up with the formula independently.

Now the question is, who gets the credit?

And on what qualification?

If it’s vintage, the Egyptians win hands down.

If it’s thoroughness, the Greeks get it.

And that’s assuming everybody came up with the formula independently.

50/50

Be that as it may, the name has now become a matter of convention. You’re free to rename it to Baudhāyana’s theorem or something like that. But do know that neither the Egyptians, nor the Iraqis have any problem calling it Pythagoras’ theorem.

SOURCES: As given in context.

Be that as it may, the name has now become a matter of convention. You’re free to rename it to Baudhāyana’s theorem or something like that. But do know that neither the Egyptians, nor the Iraqis have any problem calling it Pythagoras’ theorem.

SOURCES: As given in context.

Loading suggestions...

![[QQT: PYTHAGORAS, NEWTON, VEDAS]

1/50

Just can’t seem to catch a break, can we? What steaming fresh...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FXjPZIxaAAE2HVp.jpg)

![11/50

Translation:

The areas [of the squares] produced separately by the lengths of the breadth of a...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FXjQQBvaUAEbzsn.png)

![11/50

Translation:

The areas [of the squares] produced separately by the lengths of the breadth of a...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FXjQSF6agAI7QCC.png)

![11/50

Translation:

The areas [of the squares] produced separately by the lengths of the breadth of a...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FXjQTkbakAAlUwP.png)