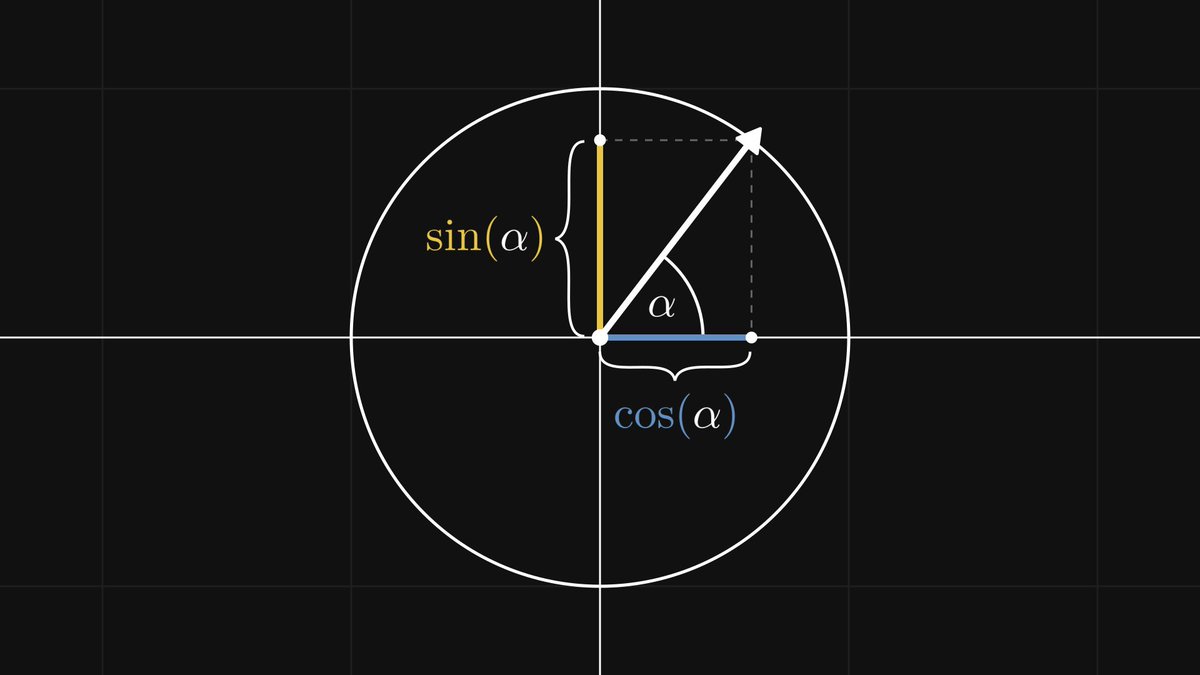

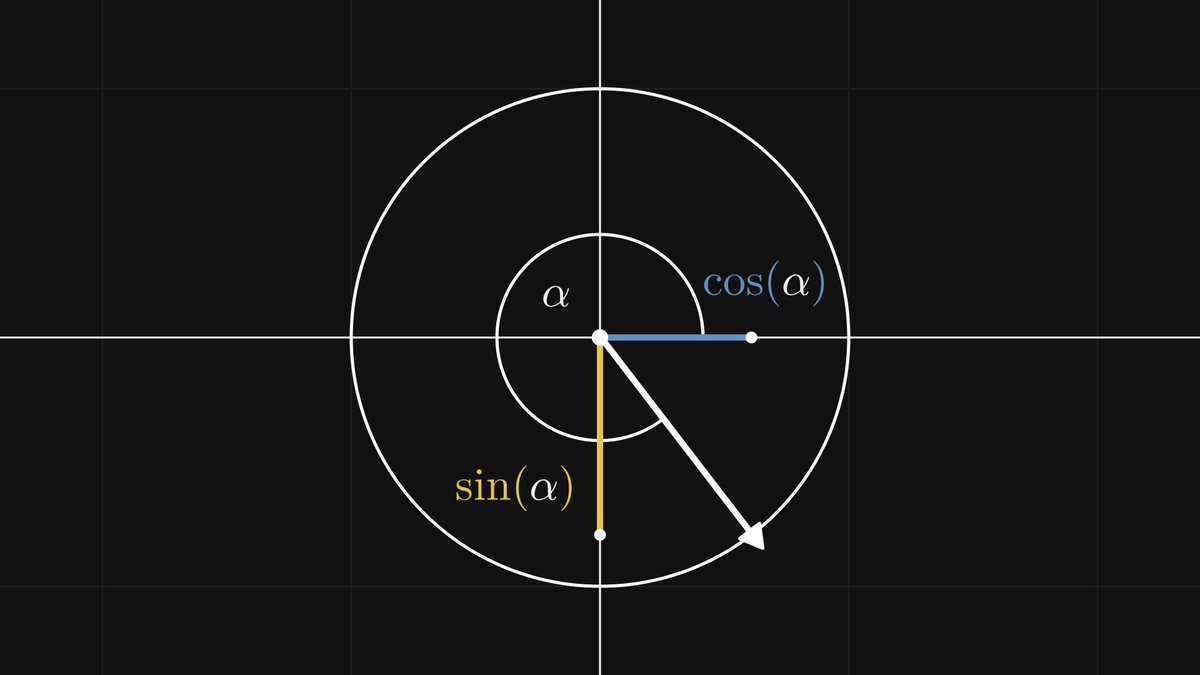

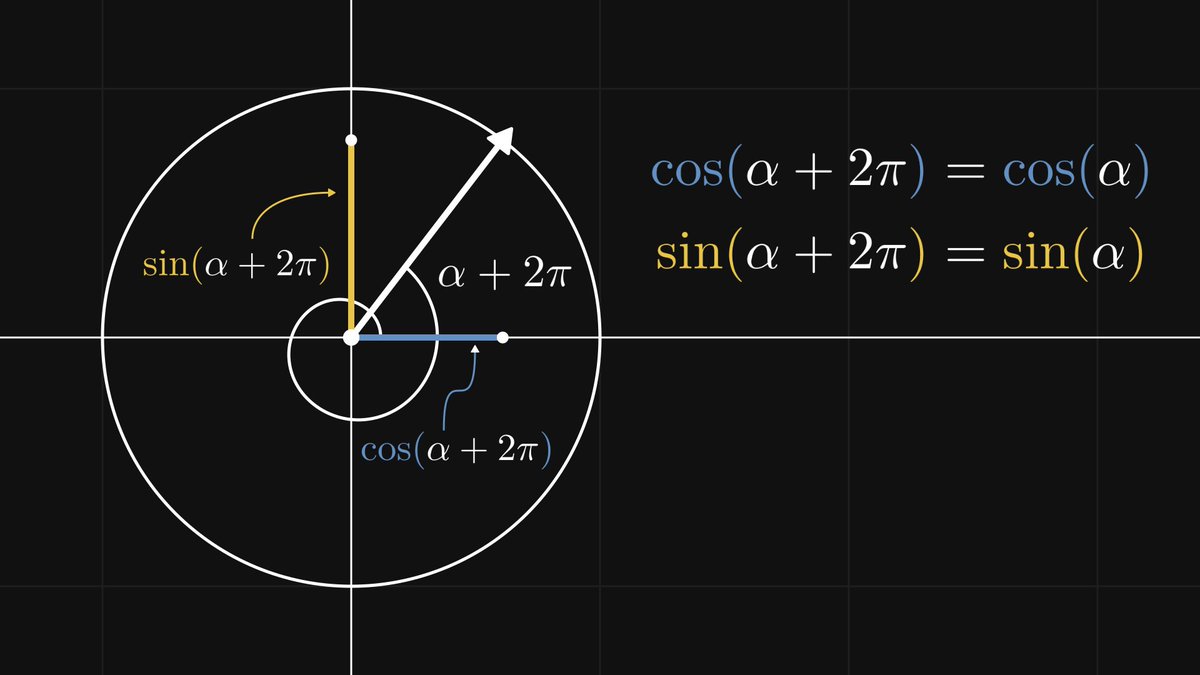

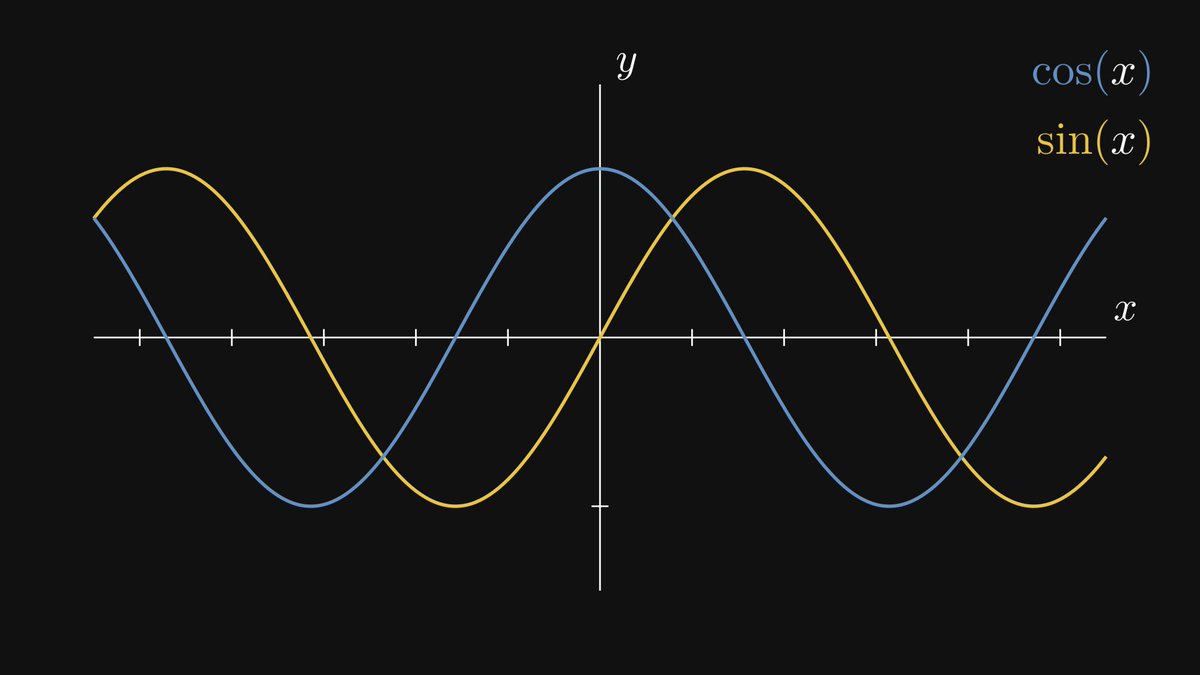

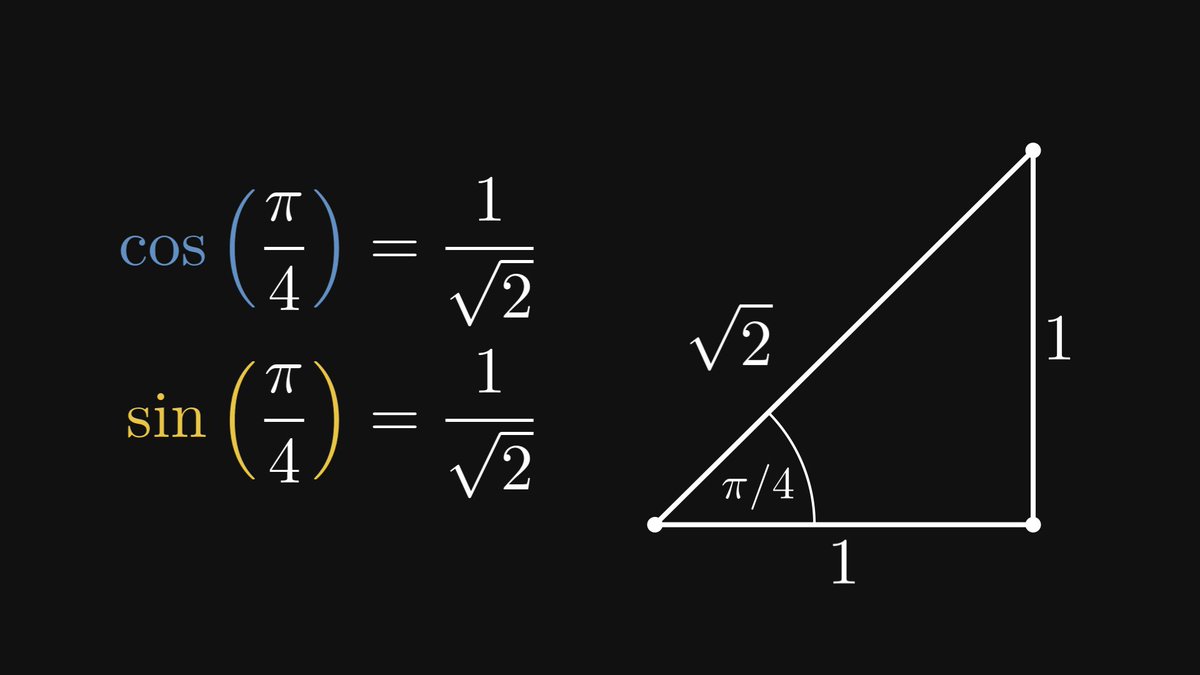

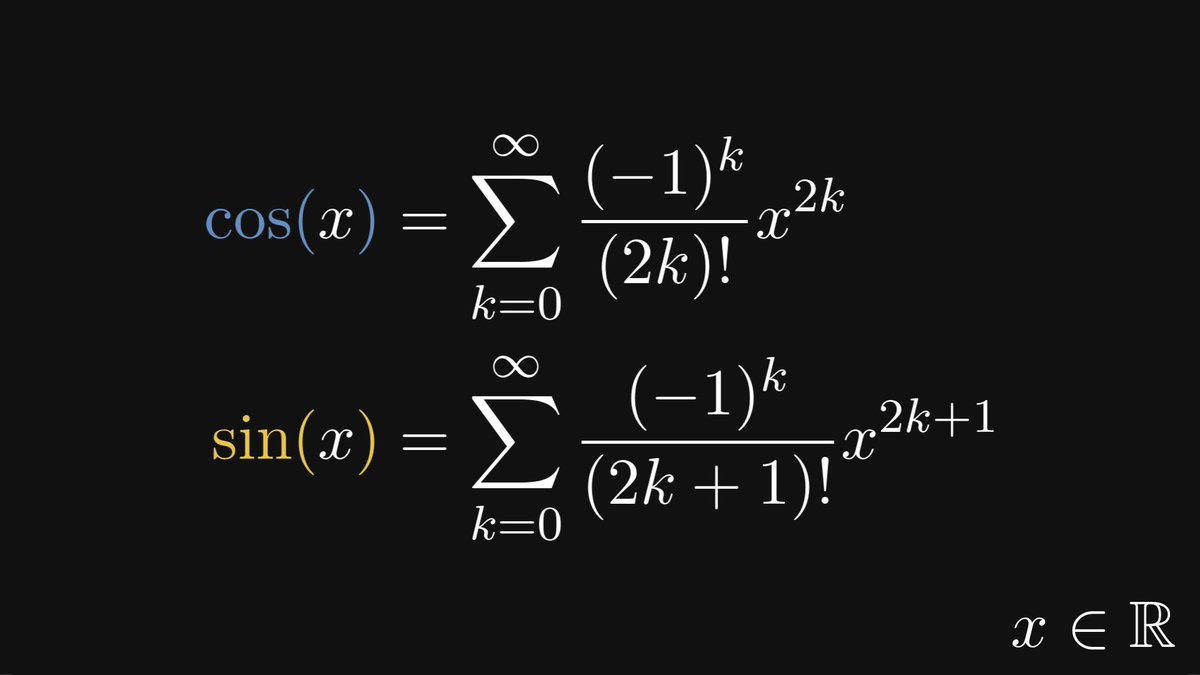

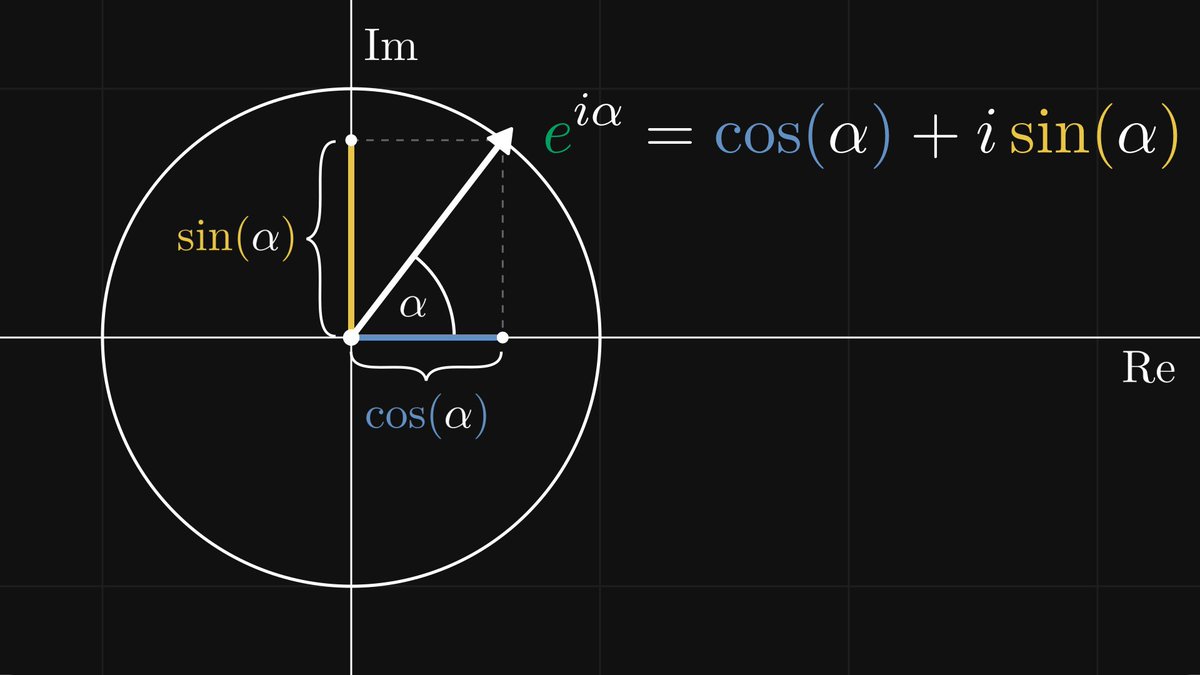

In other words, the trigonometric functions are invariant to similarity transformations. Thus, sine and cosine are well-defined: they depend only on the angle α.

Because of this, basic trigonometry is used to measure distances. Imagine a lighthouse towering in the distance. If we know its height and measure its angular distance, we can calculate how far the top of the tower is from us using sine and the Pythagorean theorem.

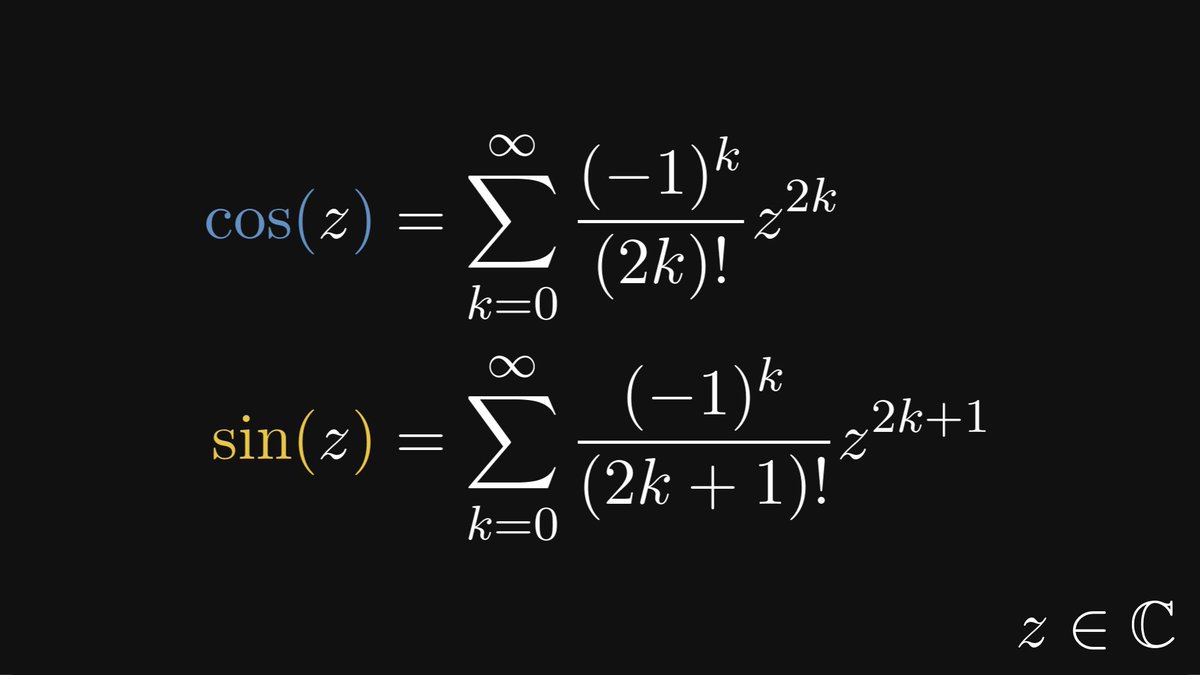

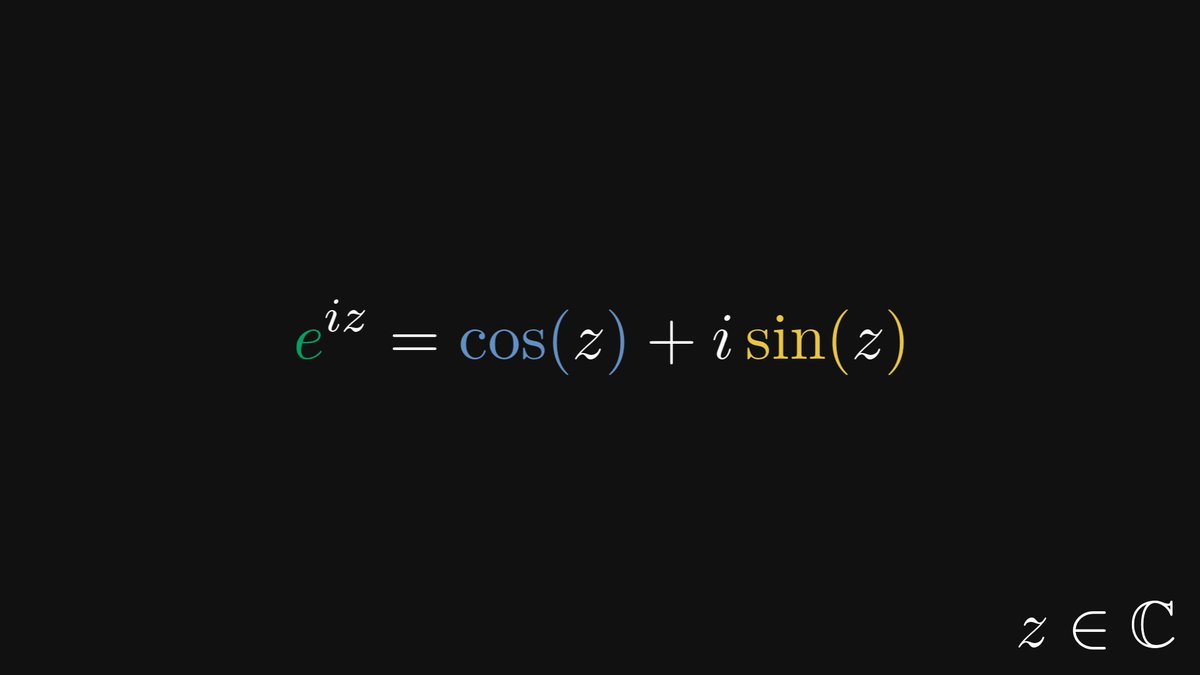

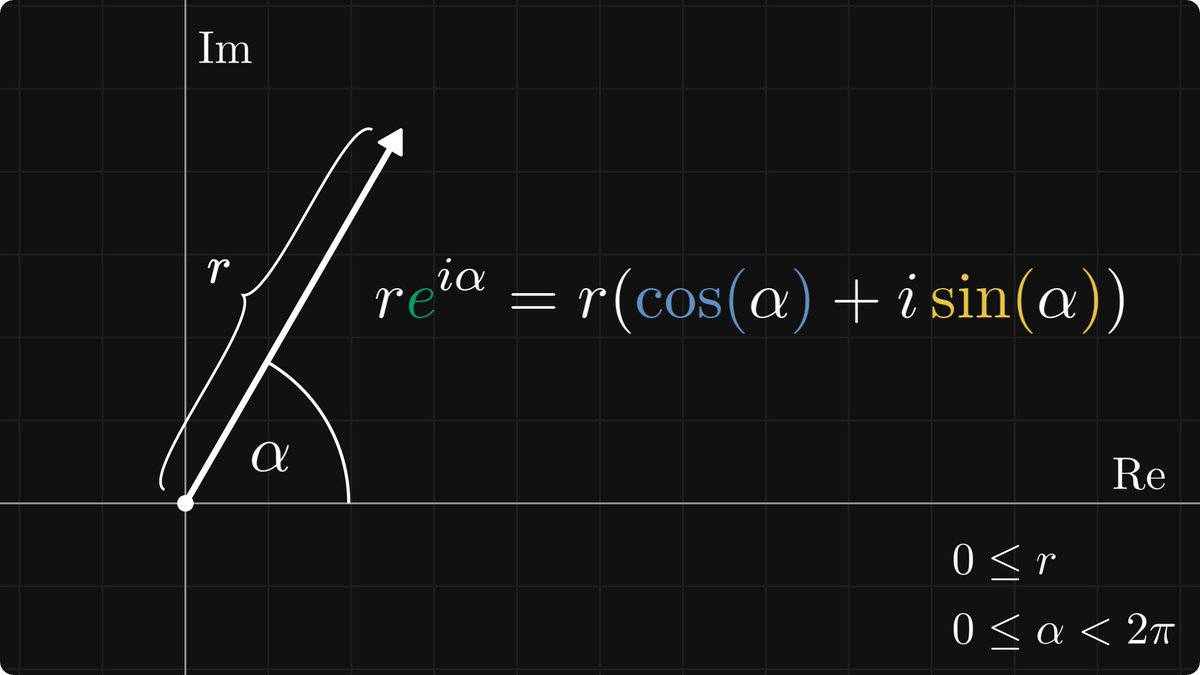

Sounds simple enough. Is it useful? Yes. Let me show you the single most mind-blowing connection in mathematics: expressing the exponential function in terms of sine and cosine.

Read the full version of the post here:

thepalindrome.substack.com

thepalindrome.substack.com

If you have enjoyed this thread, support me with a paid subscription to my newsletter!

(Or simply share this with your friends.)

Mathematics is neither dull nor dry; it’s beautiful, mesmerizing, and useful. Your support helps me show this to everyone.

thepalindrome.substack.com

(Or simply share this with your friends.)

Mathematics is neither dull nor dry; it’s beautiful, mesmerizing, and useful. Your support helps me show this to everyone.

thepalindrome.substack.com

Loading suggestions...