First, let’s address some common pushback.

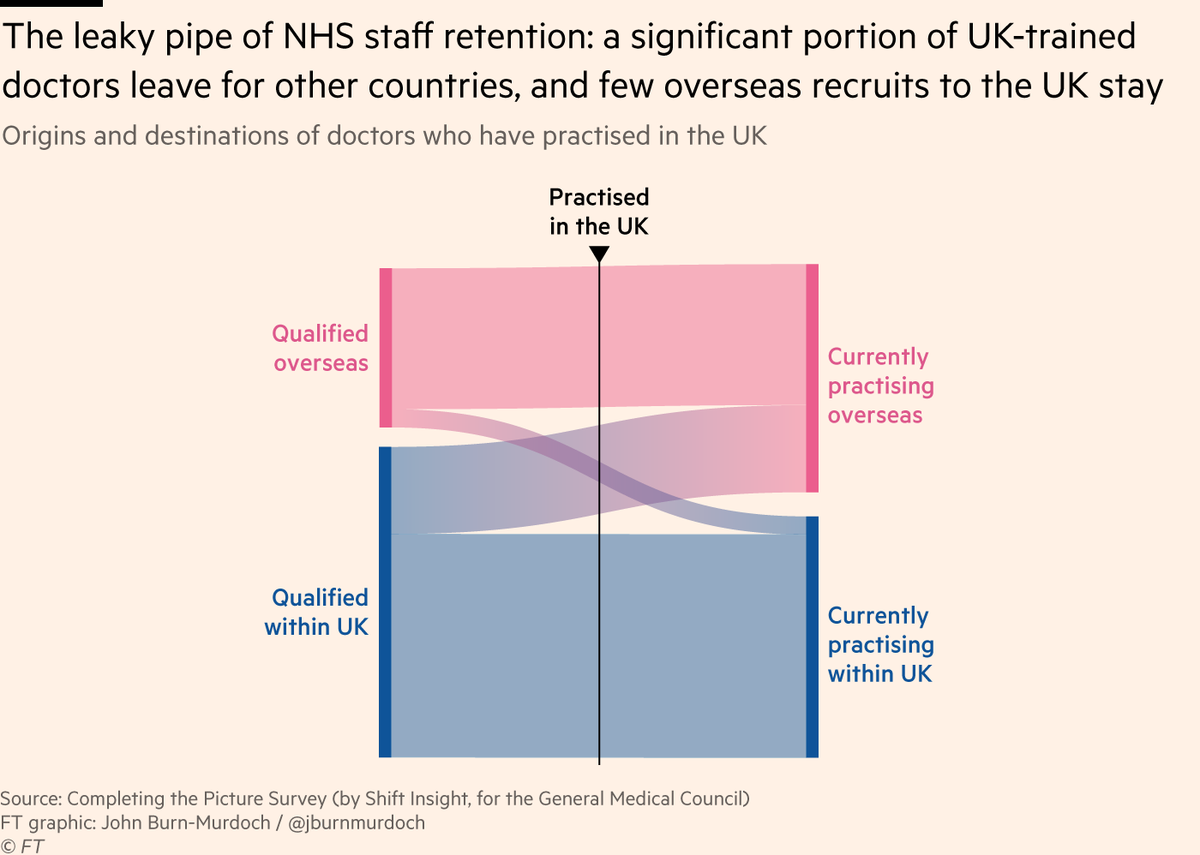

Some argue that there can’t really be a staffing crisis if the NHS can consistently recruit from overseas to make up for these departures. But there are two problems with this view.

Some argue that there can’t really be a staffing crisis if the NHS can consistently recruit from overseas to make up for these departures. But there are two problems with this view.

This means more work is carried out by agency staff or less experienced team members, which has been shown by @BenZaranko and co to increase the risk of harm to patients qualitysafety.bmj.com

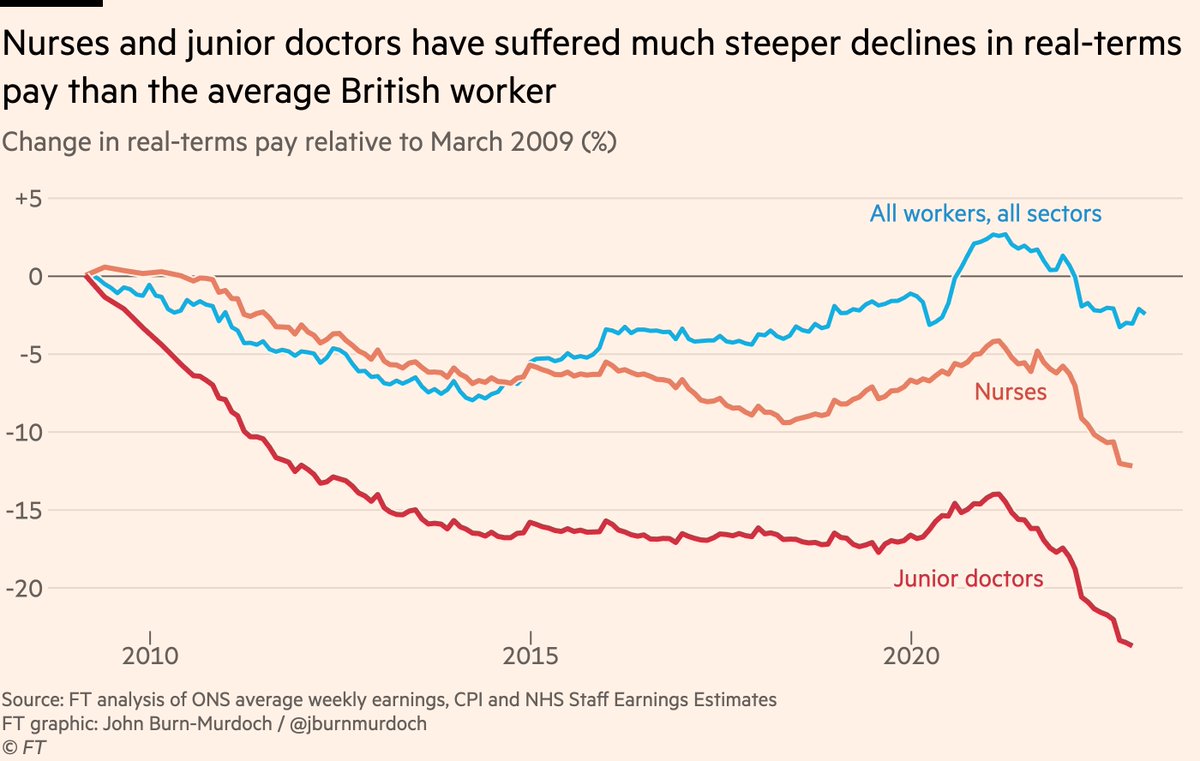

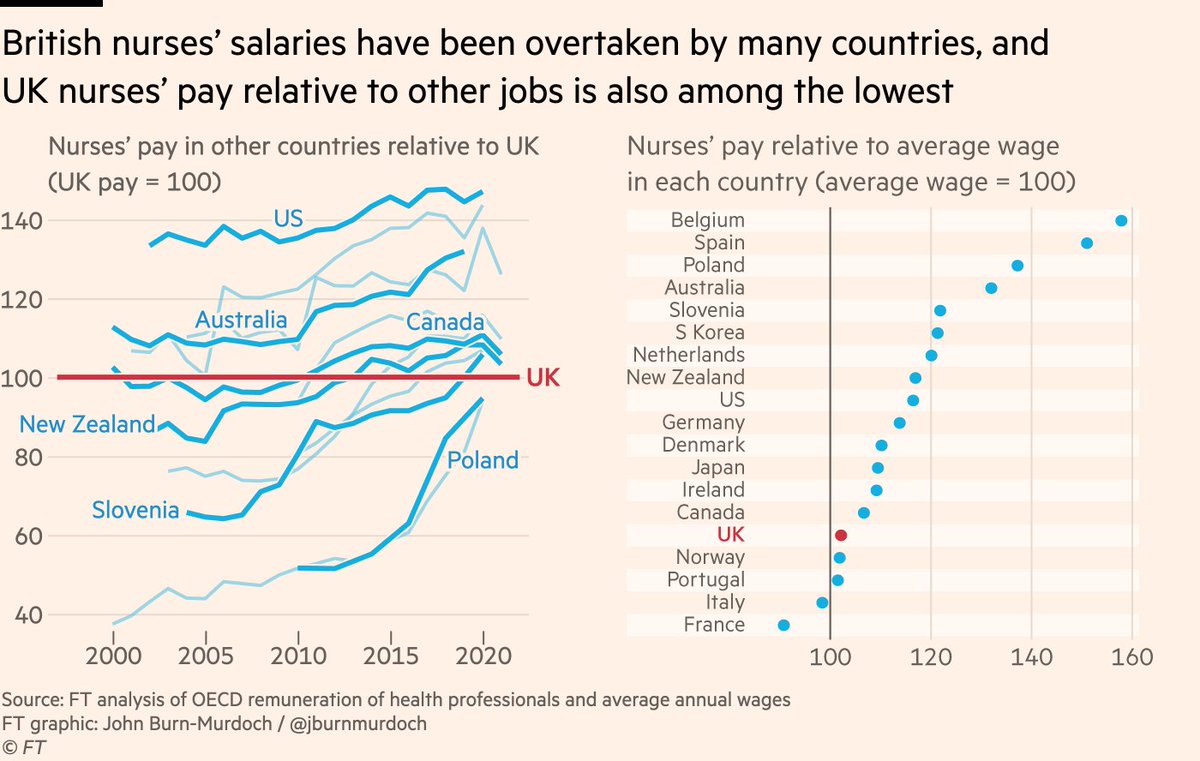

So what can be done to plug the leak? As nurses prepare for another strike on Sunday and talks between the government and junior doctors remain stalled, the most obvious and frequently mentioned solution is pay.

As the pay-off for a gruelling decade of training and an intensely stressful job diminishes, it is not surprising that they look elsewhere.

The government’s hardball stance on pay only serves to confirm British healthcare workers’ growing sense of being under appreciated.

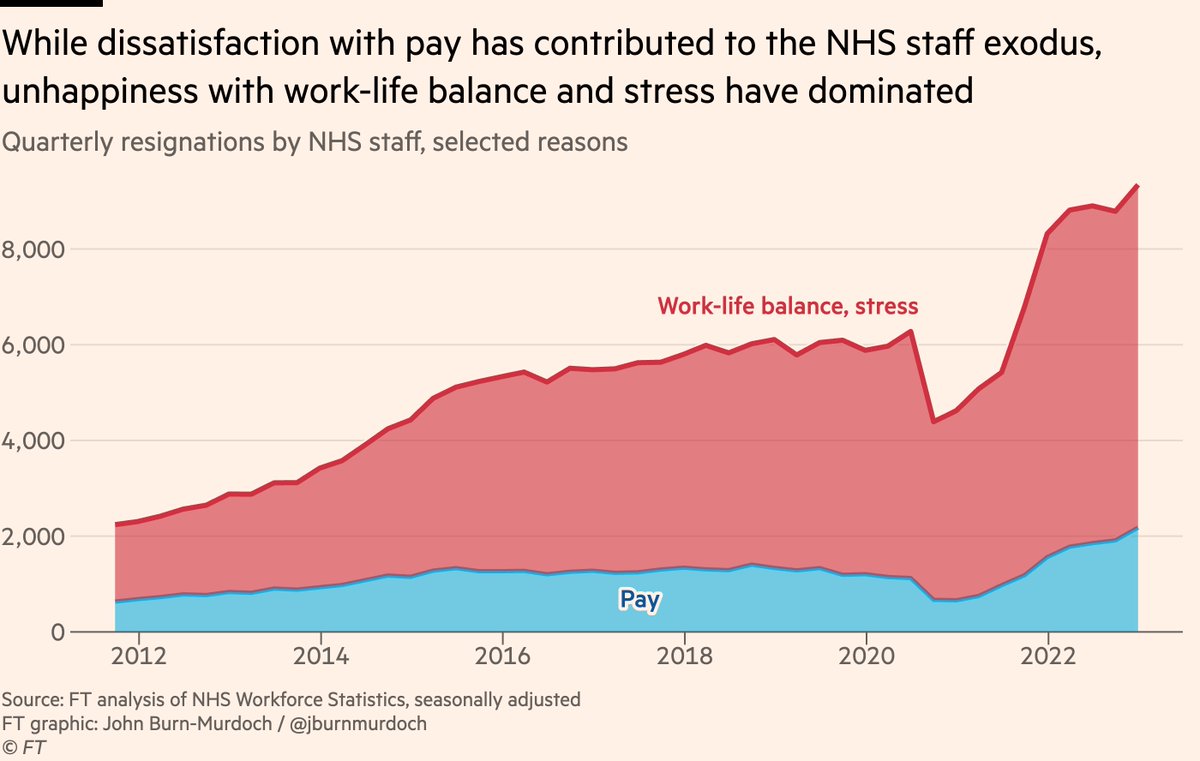

But the data here make clear that even once a deal is reached, broader and deeper changes are needed if an NHS career is to regain its allure.

But the data here make clear that even once a deal is reached, broader and deeper changes are needed if an NHS career is to regain its allure.

So, what should be done?

One thing that would help would be to increase the anaemic numbers of managers in the NHS to free up nurses and doctors to do what they were trained for.

(the NHS being over-managed is a complete myth kingsfund.org.uk)

One thing that would help would be to increase the anaemic numbers of managers in the NHS to free up nurses and doctors to do what they were trained for.

(the NHS being over-managed is a complete myth kingsfund.org.uk)

Investing in better equipment and technology to improve the experience of working on the wards would be another good step, as would more staff-specific policies such as making the process of requesting leave more streamlined and transparent.

Ultimately, many of the same things that will help alleviate pressure on the NHS as a whole in the long run will also make it less difficult to work there right now.

And here’s my column in full: enterprise-sharing.ft.com

And here’s my column in full: enterprise-sharing.ft.com

Loading suggestions...