There was a memo circulated at Western Union in 1876 which said:

"This ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us."

Another catastrophic underestimation.

"This ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us."

Another catastrophic underestimation.

Had you told Pliny or Trajan that Christianity would one day become the world's largest religion — and the official state religion of the Roman Empire — it would have been beyond laughable.

Alas, such are the vagaries of what the Romans and Greeks themselves called Fortune.

Alas, such are the vagaries of what the Romans and Greeks themselves called Fortune.

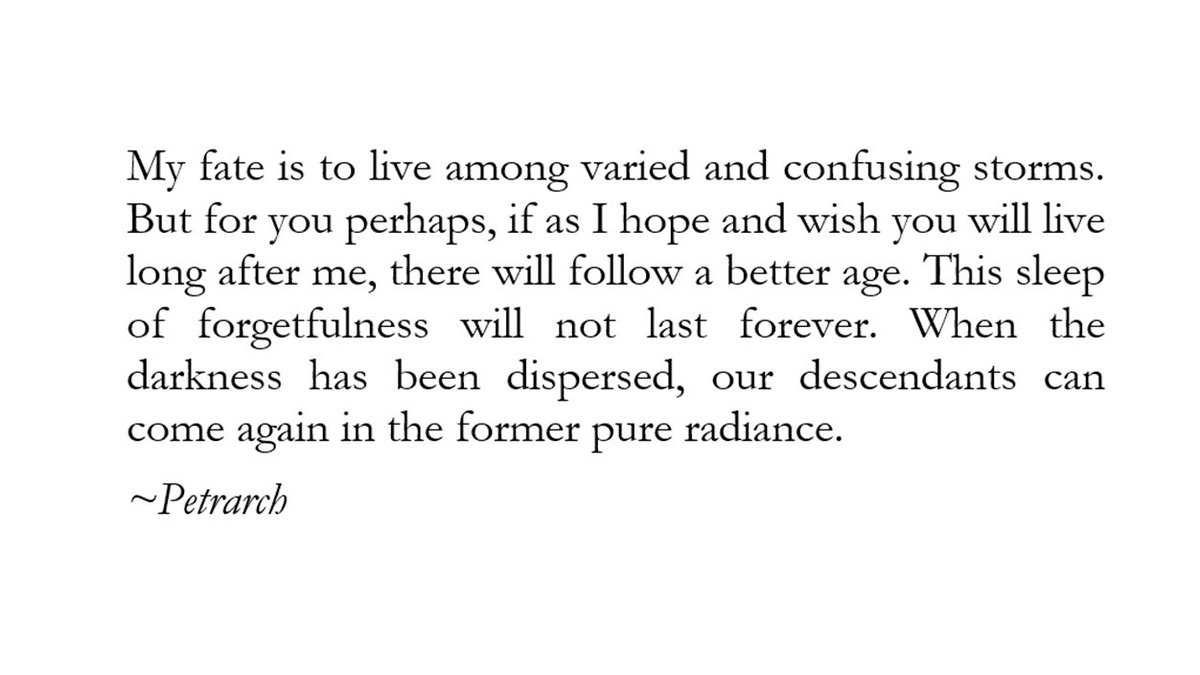

Many Medieval people believed the world was divided into Six Ages and that they were living in the very last one before the End of Times.

They certainly didn't think of themselves as living in the "Middle Ages" at all; they were waiting for the Day of Judgment to come.

They certainly didn't think of themselves as living in the "Middle Ages" at all; they were waiting for the Day of Judgment to come.

And, of course, many of history's most famously incorrect predictions came from people who we would expect to make them.

A newspaper saying the internet won't replace newspapers, or Guglielme Marconi, the inventor of radio, saying that radio would make war impossible.

A newspaper saying the internet won't replace newspapers, or Guglielme Marconi, the inventor of radio, saying that radio would make war impossible.

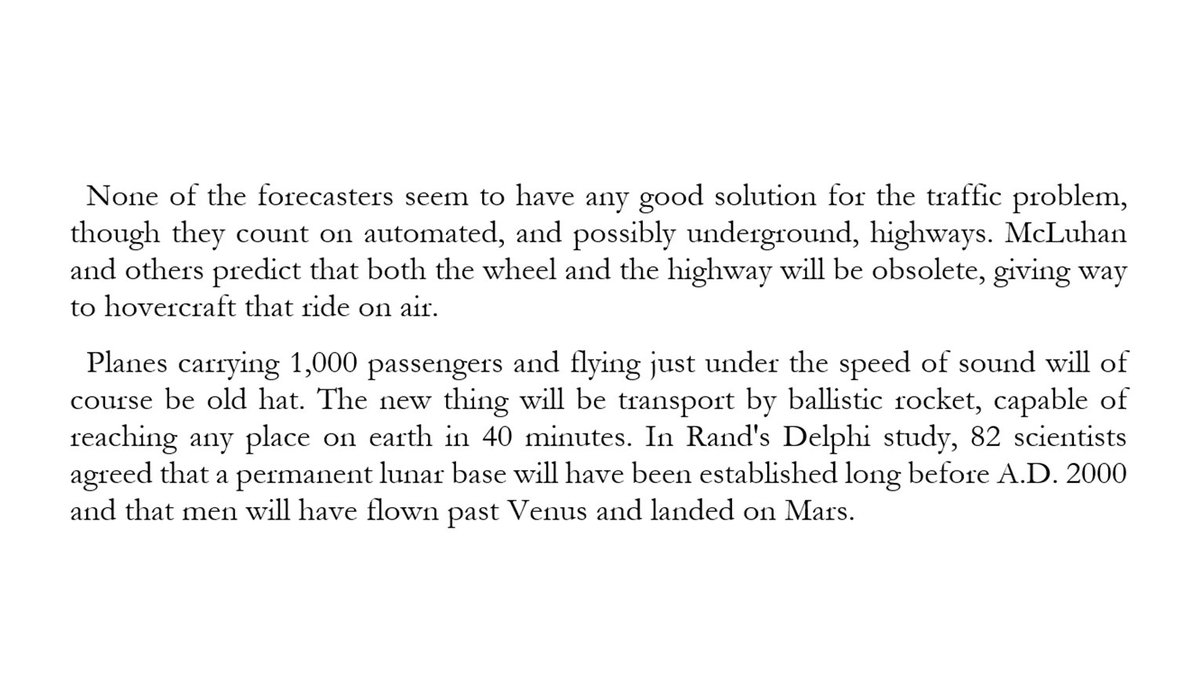

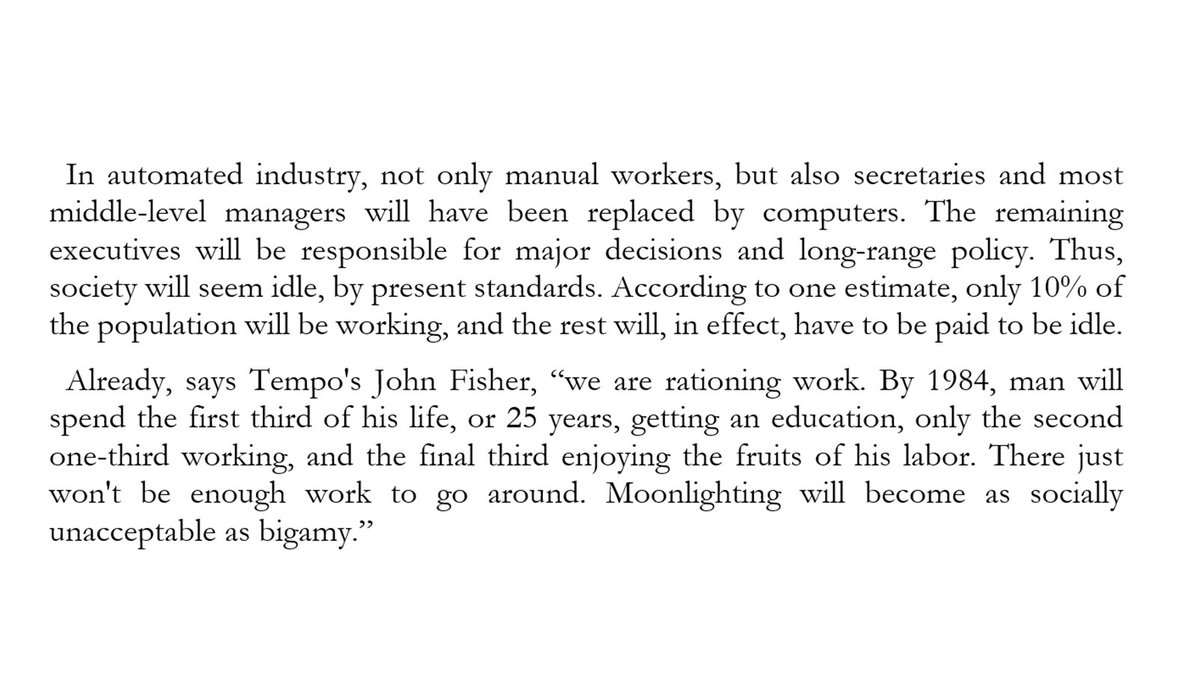

History shows that the future is not only difficult to predict, but so inconceivably capricious that even hindsight can barely make sense of it.

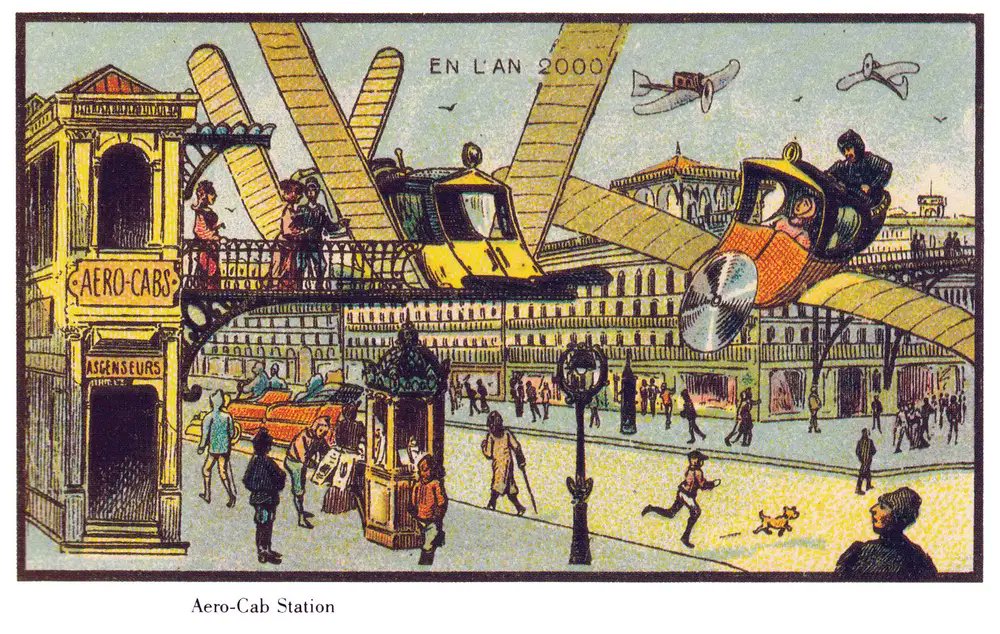

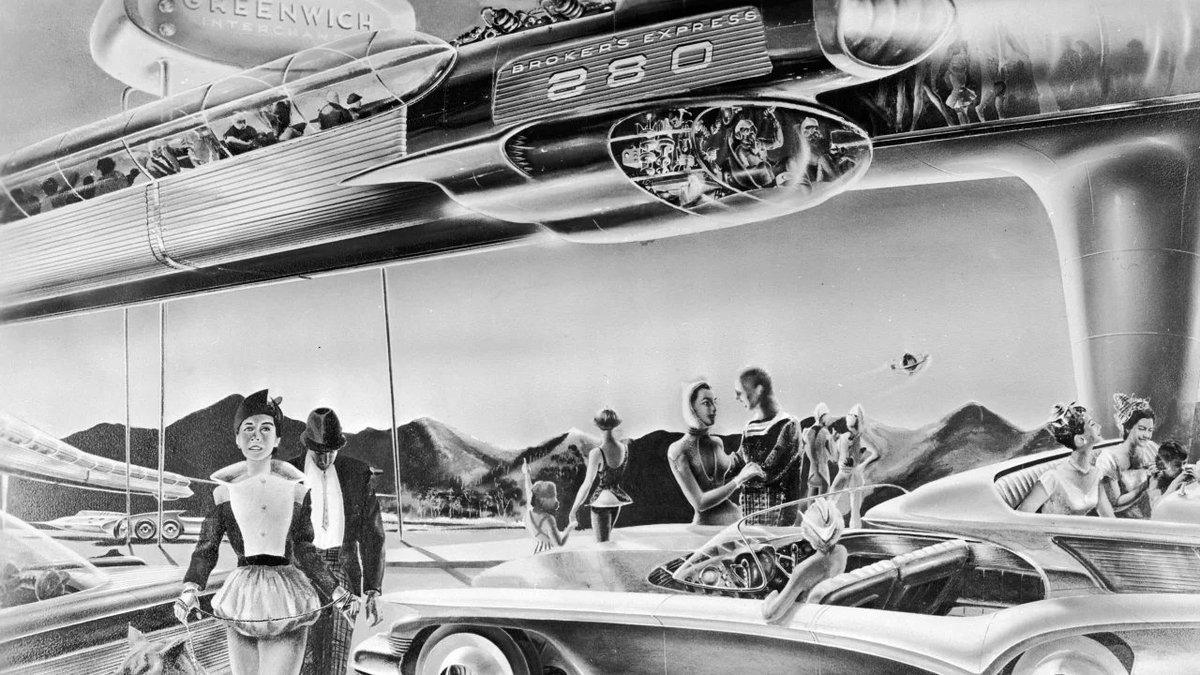

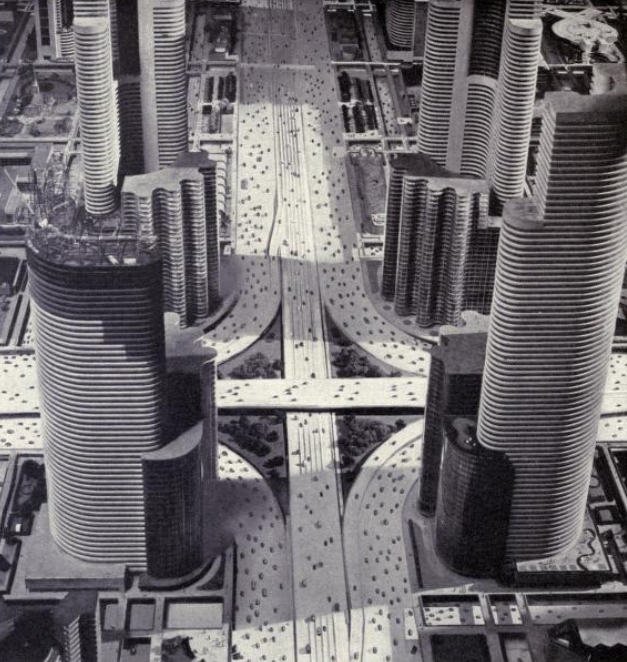

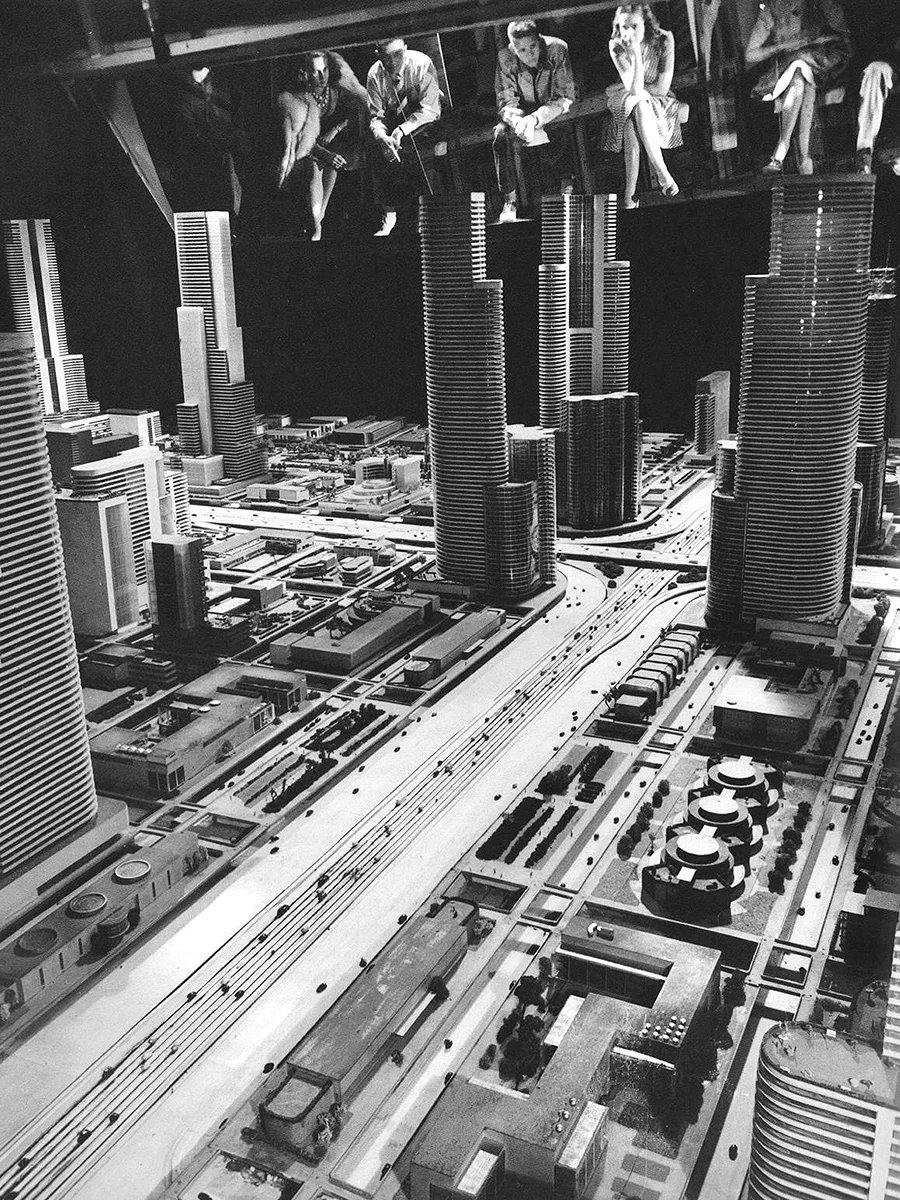

So when we imagine what the future *might* be like, perhaps what we are really asking is: what do we *want* the future to be like?

So when we imagine what the future *might* be like, perhaps what we are really asking is: what do we *want* the future to be like?

Loading suggestions...