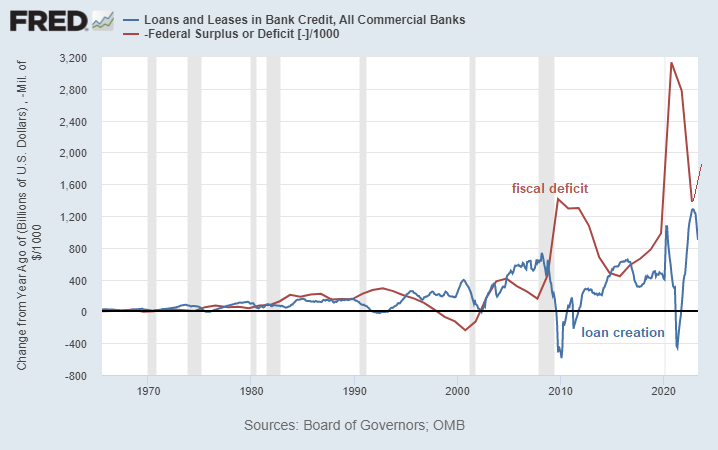

The reason this matters is that interest rates as a policy tool are mainly useful for affecting lending growth, not fiscal deficits.

Higher rates have a reputation of slowing inflation because they can put downward pressure on lending. But, they make fiscal deficits worse.

Higher rates have a reputation of slowing inflation because they can put downward pressure on lending. But, they make fiscal deficits worse.

What this suggests is that 1) interest rates are less effective as an inflation-fighting tool in the 2020s than the 1970s and 2) beyond a certain point can actually become pro-inflationary.

Lending inflation wasn't the primary driver of inflation in this cycle, but that's the only driver that the Fed can directly target.

Suppressing lending can indirectly and cyclically reduce inflation, but doesn't target the actual core causes of inflation in this cycle.

Suppressing lending can indirectly and cyclically reduce inflation, but doesn't target the actual core causes of inflation in this cycle.

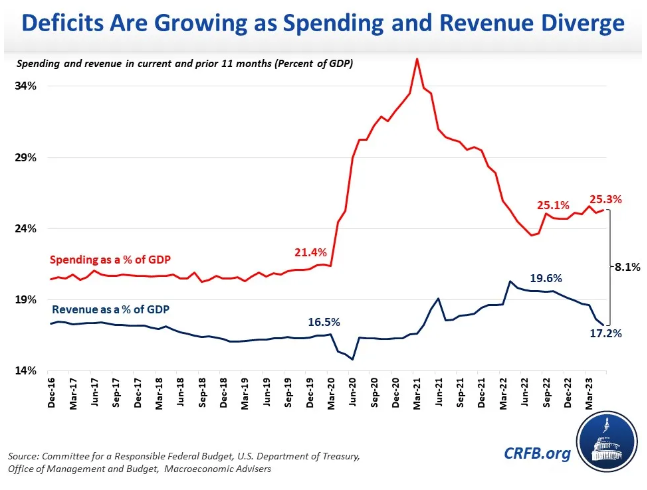

The core structural drivers of inflation currently are 1) fiscal deficits and 2) supply constraints.

Reducing the fiscal deficit, or increasing supply (i.e. energy abundance and AI/automation), are what directly tackle inflation.

Everything else just suppressed it for a time.

Reducing the fiscal deficit, or increasing supply (i.e. energy abundance and AI/automation), are what directly tackle inflation.

Everything else just suppressed it for a time.

Loading suggestions...