The strained relationship, some have argued, may have had dire consequences for the Nationalists, who lost the Chinese civil war to the Communists in 1949.

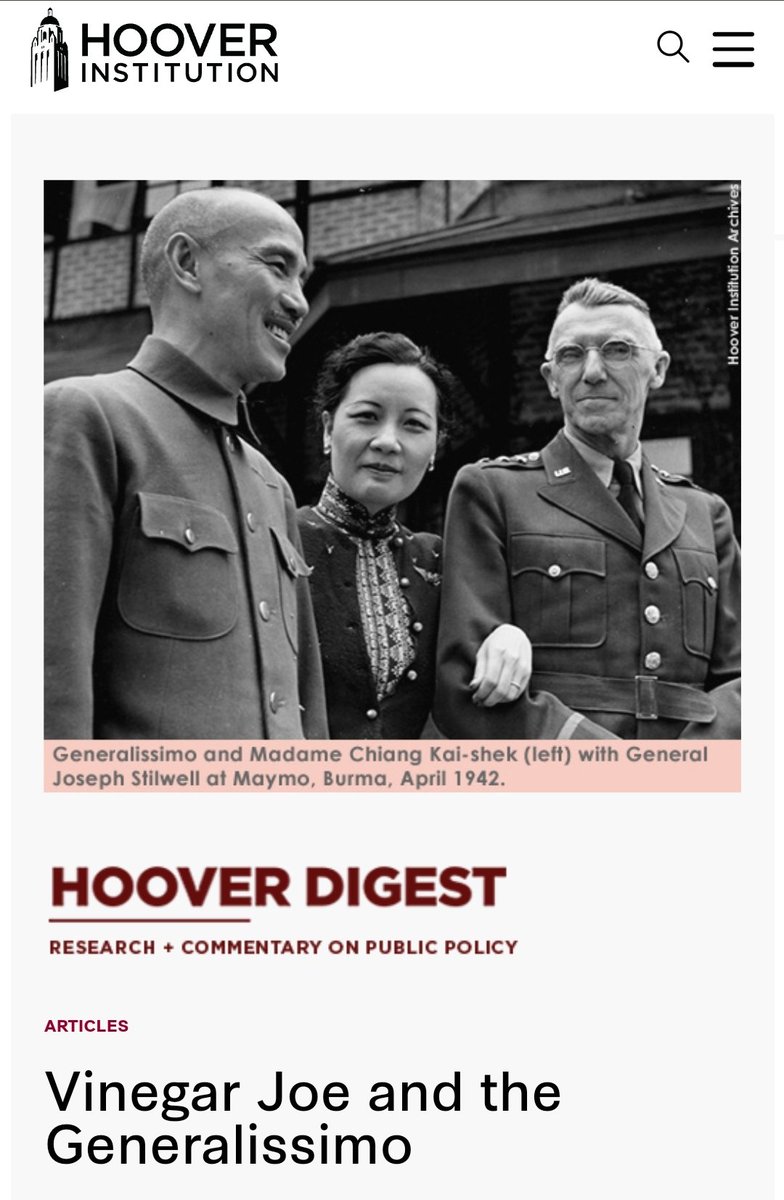

Chiang Kai-shek considered firing Stilwell as early as 1942 — and had the blessing of top American officials to do so — but ultimately chose not to.

Disagreements between Chiang and Stilwell reached a climax in late spring of 1943 over the use of American airpower and the appropriate strategy for recovering Burma.

Between July and October 1944, Stilwell repeatedly informed General Marshall of Chiang’s intransigence about cooperating with the Communists in the fight against Japan.

“The Chinese soldier,” Stilwell wrote, “is excellent material, wasted and betrayed by stupid leadership,” and he further characterized that leadership as consisting of “oily politicians…treacherous quitters, selfish, conscienceless, unprincipled crooks.”

Although the Soviet Union had provided air defense support against Japan from 1937 to 1939, the conclusion of the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact of 1939 meant that Russia was now a nominal ally of Japan; consequently, all Soviet assistance to China ceased.

China turned its gaze toward the US. For its part, in Washington, the Roosevelt administration sympathized with China’s plight but American largesse was sharply limited by President Franklin Roosevelt’s policy of neutrality in the Sino-Japanese war.

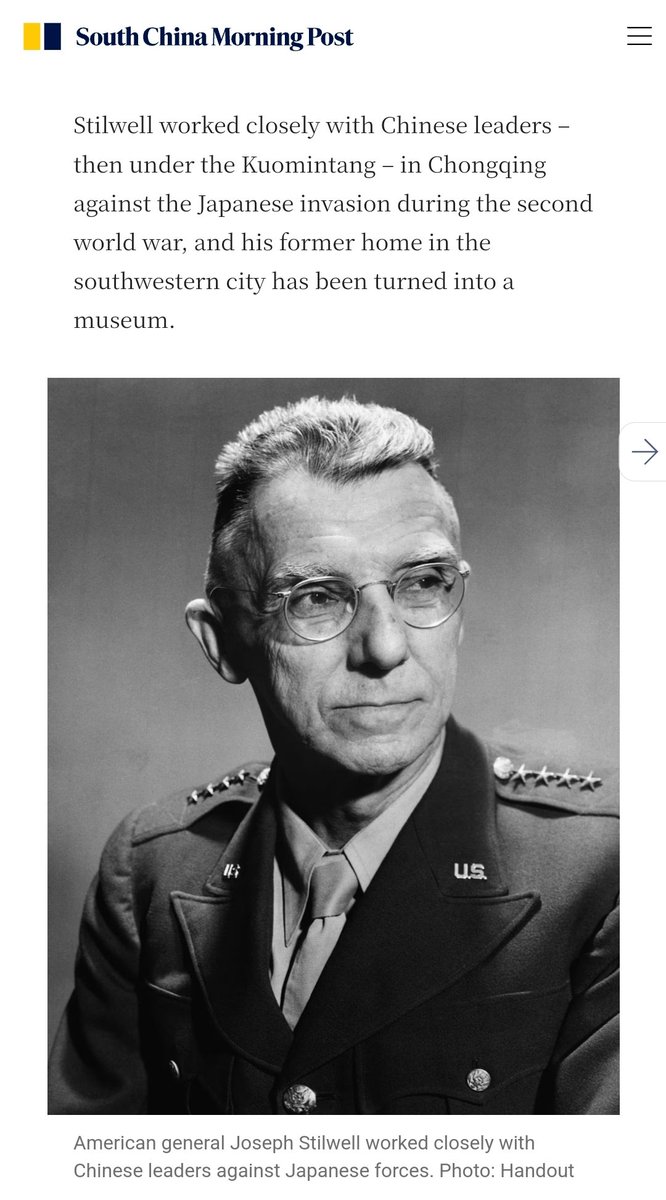

At every turn, Chiang resisted Stilwell’s meddling. United States, however, badly needed Chiang’s troops to engage the one million Japanese ground forces stationed in China so that they wouldn’t battle American troops elsewhere in the Pacific.

Even before the Cairo Conference, Stilwell had told Carl F. Eifler, the senior American intelligence officer in China, that to fight the war successfully there, “it would be necessary to get Chiang out of the way.”

Especially after the United States came into the war at the end of 1941, Chiang frequently refused to go on the offensive against Japan, keeping several hundred thousand of his best troops in reserve to guard against the expansion of Mao’s party in the north.

Chiang was no liberal democrat: His much feared secret police, which Stilwell likened to the Gestapo, maintained a regime of surveillance, imprisonment, and — on occasion — execution of real and suspected opponents.

Contrary to popular perception, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek did fight: He mounted a brave, veritably suicidal, resistance to the initial full-scale Japanese invasion of 1937.

The only ones really interested in saving China were China’s communists, captained by Mao Zedong, who even flirted with the idea of maintaining an equal distance between Washington and Moscow. But America backed the wrong horse and pushed Mao away.

New books however reveal that far from being a strategic visionary, Stilwell committed a string of disastrous military mistakes that resulted in the slaughter of tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers — damaging Chiang’s ability to defend his country first against Japan.

Mao’s armies conducted what he called a “sparrow war,” limited to small-scale guerrilla attacks. In fact, the communists lost more troops in attacking their erstwhile nationalist allies than in fighting the Japanese.

Rana Mitter argues China’s experience during WW II — from Japanese atrocities, to the dysfunctional relationship it developed with the US, to the new demands put on the population by both the KMT and CPC — is critically important to understanding many of China’s issues today.

In Mitter’s telling, Stilwell, who had no command experience before his tour in China, comes off as a petulant, small-minded, strategically limited, diplomatically tone-deaf leader obsessed with one thing only: Burma, which, Mitter notes, was “a target of dubious value.”

After the Cairo summit, which Chiang and his wife Soong Meiling attended along with Roosevelt and Churchill, Roosevelt told the American people that the US and China were closer than ever before. The truth was that the US was beginning to wonder whether Chiang would survive.

Both Chiang and Mao were from rural families. Both were attached to their mothers and hated their fathers. Both were ruthless and ambitious, and neither could be described as attractive human beings.

Chiang was a neurotic despot whose treatment of those close to him was startlingly heartless. He abandoned his first wife, gave his second STD on their wedding night and, despite her exemplary conduct, discarded her in favor of an advantageous match with Soong Meiling.

The KMT regime held power for short periods, but was always embattled and never succeeded in gaining control over the whole of China. Even so, there were reforming and modernizing impulses that might have guided China towards a happier future had conditions allowed.

Wedemeyer returned to the Far East in 1947 as a special fact-finding ambassador for President Truman. The long-unpublished report of that mission subsequently became a major focus of controversy in the bitter foreign policy debates of the 1950s.

As China descended into communist rule in the 1950s, it was used by some Americans such as Joe McCarthy, and even an ambitious Democratic congressman from Massachusetts named John F. Kennedy, as an example of America’s “moral retreat” from its responsibilities to save China.

Marshall’s failure to unite China’s Nationalist and Communist parties, which had been at war since 1927, into one government and one army must have been part of a communist plot, the charges went, because if it had wanted to, America could have accomplished anything.

As negotiations collapsed and the civil war raged, Marshall washed his hands of China and left Chiang to his fate. The alternative, Marshall told Congress, would be for the US to “take over the Chinese gov't, practically, and administer its economic, military, and gov't affairs.”

On the one hand, the U.S. regarded Chiang as indispensable, the only person who could hold China together; and at the same time, American emissaries pressured him into political reforms and military actions that, he was sure, would have destroyed him.

The irony is that none of these pressures were put on the Communists; nor was it generally recognized that they were following the same strategy as Chiang, holding their forces in reserve so they'd be available for the civil war to follow.

China had no tradition of democratic power sharing, so the expectation that either the Communists or the Nationalists would behave like American Democrats or Republicans was unrealistic to begin with.

Stalin's vigorous, if often clandestine help to the Communists, which began right after the war, gave Mao great confidence that he could never be defeated militarily by the KMT government and he therefore had no real incentive to agree to any permanent compromise solution.

With increasing alarm, Truman's foreign policy and defense advisors had come to see a Soviet Union bent on imposing communism on the rest of the world — a chilling declaration that Winston Churchill eloquently expressed in his famous "Iron Curtain" speech in early 1946.

Events in early 1947 had placed the United States in direct conflict with the Soviets' perceived hegemonic aims. In February, Great Britain informed the Truman administration that it could no longer afford to keep the peace in Greece and Turkey in the wake of a budget crisis.

That Chiang was a corrupt leader in charge of an inept army was obvious to anyone with even a passing knowledge of China. Truman's political enemies, however, saw China's woes in a far different light.

Foremost among those critics was Time publisher Henry Luce, born in China to missionary parents, who argued that the communist victory was a result of American irresolution, not Chiang's perfidy.

Speaking to a veterans group in January 1950, then U.S. Representative John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts said Truman should send troops to Formosa and blamed him for Chiang's failure in China.

When Marshall visited the Communists’ remote revolutionary headquarters, Mao declared, “The entire people of our country should feel grateful and loudly shout, ‘long live cooperation between China and the United States.’”

In the fall of 1949, Mao Zedong stood atop Beijing's Tiananmen gate and proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China. The United States, however, refused to recognize Mao's Communist regime as legitimate.

Forging a relationship with Communist China from the start would have had several advantages for the U.S., not least by driving a wedge between China and the USSR. This was the strategy that ultimately drove the Nixon Administration to seek rapprochement with China in 1972.

But U.S. policy toward China could have been worse. In establishing his policy toward China in 1949, President Truman also resisted calls from hawkish elements within the U.S. government to arm Chiang Ka-Shek to take back the Chinese mainland.

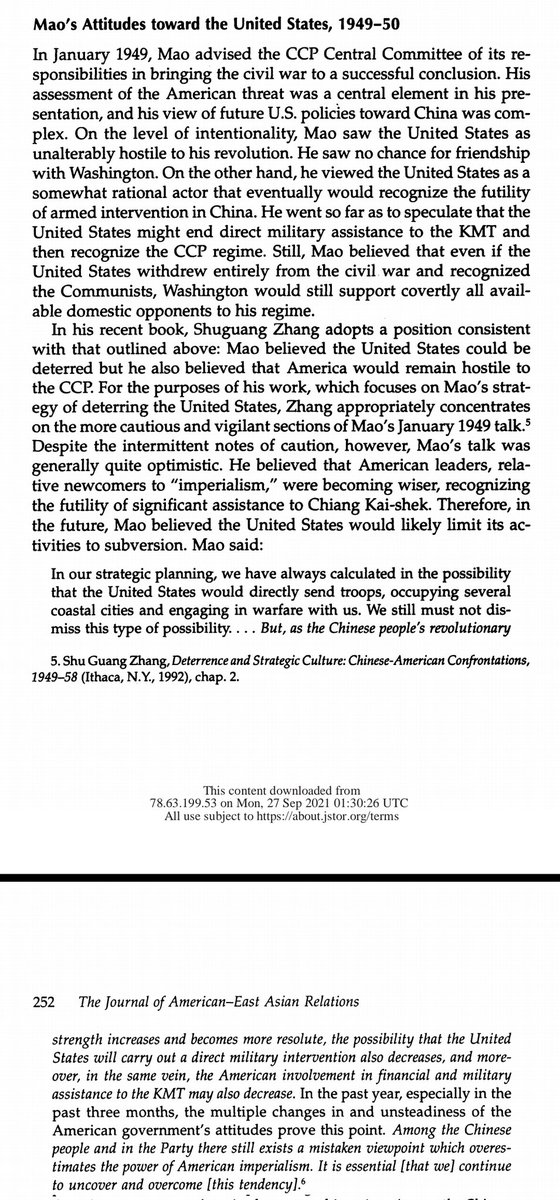

Mao saw the United States as unalterably hostile to his revolution.

jstor.org

jstor.org

For Mao, Washington’s blocking of his plan to “liberate Taiwan” meant that a war between China and America had already begun.

wilsoncenter.org

wilsoncenter.org

Mao’s motivations to intervene in Korea were much more complex. He saw China’s responsibilities for the socialist camp. He was enraged that US Seventh Fleet had been sent into the Taiwan Strait. He was very concerned about the safety of China’s northeastern borders.

Stalin’s reneging on his promise of Soviet air support, even if it meant giving up North Korea, put Mao in an awkward position. But Mao remained determined to send troops to Korea. He realized that Stalin did not really mean to abandon North Korea.

China’s decision to enter the war played a decisive role in convincing Stalin that Mao and his comrades were “genuine internationalist Communists.” Shortly after Chinese troops crossed the Yalu River, Stalin ordered the Soviet air force to help defend the Chinese supply lines.

Co-ordination between Mao and Stalin in the early 1950s fuelled American determination to halt the spread of communism. That led to America fighting wars in Korea and Vietnam, its commitment to defend Taiwan, and many proxy conflicts elsewhere.

Chinese officials are wary of moves by America and its allies to portray China as explicitly backing Putin’s war.

Loading suggestions...