has been a subject of controversy both in the popular understanding of American history and amongst academic circles for decades.

Why, if the wheel and axle have been understood since at least 1700 BCE, did such complex societies, with cities, urban organization, roads -

Why, if the wheel and axle have been understood since at least 1700 BCE, did such complex societies, with cities, urban organization, roads -

public infrastructure and large economic trade networks did not go the extra step and adapt this technology for ease of transportation and travel?

Numerous convincing arguments have been proposed to address this historical "inconsistency"

Numerous convincing arguments have been proposed to address this historical "inconsistency"

From lack of beasts of burden, to the actual physical effort demanded from carts and wheelbarrows that don't actually translate to more efficient transportation, to the over abundance of manpower, to the religious concept of hard labor as godly tribute, to mountainous geography

Which placed together give a pretty firm and consolidated answer as to why they didn't use them for large scale transportation.

And yet, what if they did?

And yet, what if they did?

Since at least 1945, Alfonso Caso, Matthew Stirling, Samuel Lothrop, Eric Thompson, José García Payón and Gordon Ekholm, posited the possibility that the wheeled “toys” where in fact miniatures of wooden tools that have not survived the test of time, citing numerous examples

of rotary tools used for the spinning of cotton, the leveling of roads in the mayan peninsula, the elaboration of round pottery, etc.

(mexicolore.co.uk)

(mexicolore.co.uk)

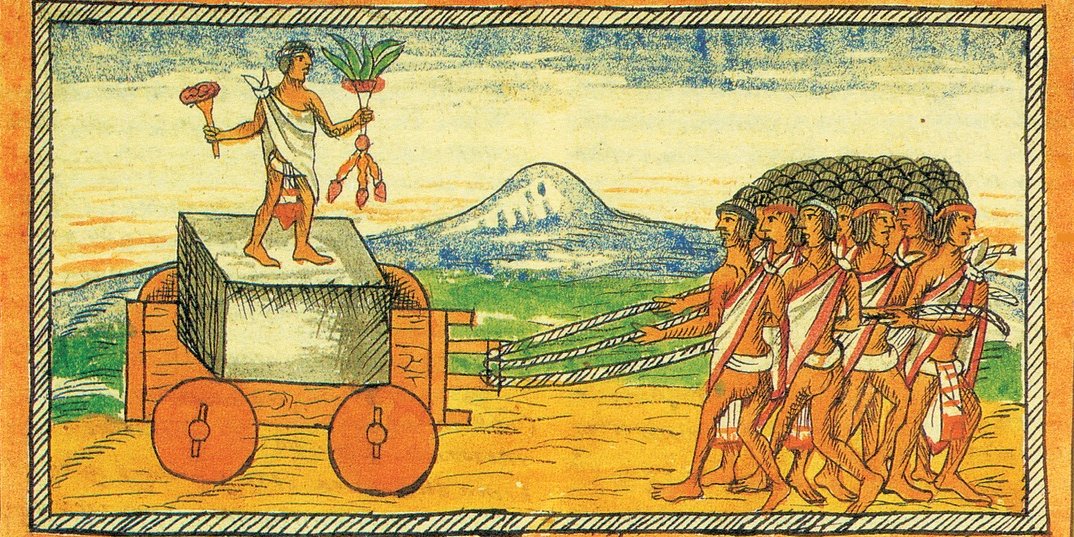

Now, for context, the above image (upon which my illustration is based on) is a plate from the Jesuit priest's nominal work "History of the Indies of New Spain and the Mainland Islands".

In it are numerous Chalca workers who, by orders of Motecuhzoma II, are transporting a

In it are numerous Chalca workers who, by orders of Motecuhzoma II, are transporting a

lithic piece to be carved into a giant gladiatorial stone for the consecration of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan.

The illustration was done by a nahua tlacuilo (artist/writer) commissioned by Durán. Curiously however, the actual text itself doesn't cite the exact way in which

The illustration was done by a nahua tlacuilo (artist/writer) commissioned by Durán. Curiously however, the actual text itself doesn't cite the exact way in which

this stone was transported.

By itself one might assume this artistic piece is nothing more than a superposition of the colonial reality into the pre-hispanic past, by an artist and historian who couldn't concieve of a way to move such a large object by manpower alone.

However -

By itself one might assume this artistic piece is nothing more than a superposition of the colonial reality into the pre-hispanic past, by an artist and historian who couldn't concieve of a way to move such a large object by manpower alone.

However -

There are numerous reasons to believe this isn't the case.

First is the second line of evidence:

Alvarado Tezozomoc.

First is the second line of evidence:

Alvarado Tezozomoc.

Tezozomoc was a Mexica (yes, mexica) historian who was the grandson of none other than Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, or Moctezuma II as he is frequently known.

Through the recollection of surviving codices and the recollected oral tradition of living mexica who witnessed and lived

Through the recollection of surviving codices and the recollected oral tradition of living mexica who witnessed and lived

through the period of transition from "Cem Anahuac" to the Viceroyalty of New Spain, he compiled an incredible history of the Aztec empire, which has been consistently corroborated by modern scholars and archaeologists alike.

It is likely than his work (the Chronicle X) was the

It is likely than his work (the Chronicle X) was the

source of most of Duran's work, and thus corroborates the plates with two important passages.

The first, in reference to Emperor Axayacatl commissioning a large gladiatorial stone for the consecration of the Great Temple in celebration of his victory against the Matlatzincas:

The first, in reference to Emperor Axayacatl commissioning a large gladiatorial stone for the consecration of the Great Temple in celebration of his victory against the Matlatzincas:

About fifty thousand Indians gathered together with thick ropes and carts and went to remove a large rock from the foot of the large mountain range of Tenan de Cuyuacan

The second, in reference to Motecuhzoma II:

"...to the old singers with teponaztli and to the priests with cornets and tied them, and they brought it very quickly with many carts..."

"...to the old singers with teponaztli and to the priests with cornets and tied them, and they brought it very quickly with many carts..."

Both from the Cronica Mexicana, a spanish translation of the Cronicle X attributed as well to Alvarado Tezozomoc.

It is important to remember that in both cases, the medieval scholars are using sources who lived through these events and possibly took part of them directly.

Yet in the illustration alone there is reason to believe they aren't imposing colonial technology into the past.

Yet in the illustration alone there is reason to believe they aren't imposing colonial technology into the past.

Firstly, is that there are no other examples within the corpus of illustrations that place colonial technology, clothing or other cultural attributes into these past scenes.

Please recall that these illustrations and texts are within living memory of the events.

Please recall that these illustrations and texts are within living memory of the events.

There are numerous ways one could interpret this, of course:

One is that the tlacuilo could not imagine any way to transport that stone other than by cart, but he made the conscious decision not to use a colonial reference.

One is that the tlacuilo could not imagine any way to transport that stone other than by cart, but he made the conscious decision not to use a colonial reference.

Another is that he used a reference with which he was already extensively familiar (toys?) and not a cart that by 1588 would be fully visible to the artist in Mexico-Tenochtitlan.

Or third, and perhaps just as likely, is that he drew what he and his informants were already familiar with, for the transportation of such a large unwieldy object.

Is it so hard to imagine?

Is it so hard to imagine?

Frequently we take for granted assumptions about the technological development of the people of the Americas based on centuries of racism and concerted efforts to erase their presence and claims to the land.

These takes are often wrong, made in bad faith and dismissive of -

These takes are often wrong, made in bad faith and dismissive of -

the historical sophistication of these cultures.

What is important to remember though, is that even the conquistadors themselves didn’t recognize much of any technological “superiority” to the natives of Mesoamerica, often using phrases such as "in the way of the natives" or

What is important to remember though, is that even the conquistadors themselves didn’t recognize much of any technological “superiority” to the natives of Mesoamerica, often using phrases such as "in the way of the natives" or

"the way the Indians do it," to refer to differences in technical methodologies, and when there are none, they do not mention it. Focusing instead on their perceived theological failings.

That being said, they weren’t unaware of that which the natives lacked, from Francisco Hernandez (1571) they knew they lacked iron but knew bronze, that of steel they had no swords, guns, horses and beasts of burden, that they didn’t make use of candles nor doors, nor that

they wore any of the clothes popular in the old world, and of course, that they didn’t know of Jesus Christ (lol). And yet, no mention of wheels.

So, did Mesoamericans use wheels for "practical" purposes?

Perhaps, perhaps not. Only time and further archaeological research will tell.

The gladitorial stone Motecuhzoma comissioned never made it to Tenochtitlan, crashing and sinking into the lake Texcoco

Perhaps, perhaps not. Only time and further archaeological research will tell.

The gladitorial stone Motecuhzoma comissioned never made it to Tenochtitlan, crashing and sinking into the lake Texcoco

in one of it's causeways. Perhaps the stone, and evidence of these large contraptions still lies their, beneath Mexico city.

Ayo, I have a Patreon where I post a ton of paintings of ancient and medieval America that are much cooler than this quick sketch I pulled together for this thread lol, please check it out and follow me for more stuff!

patreon.com

patreon.com

Loading suggestions...