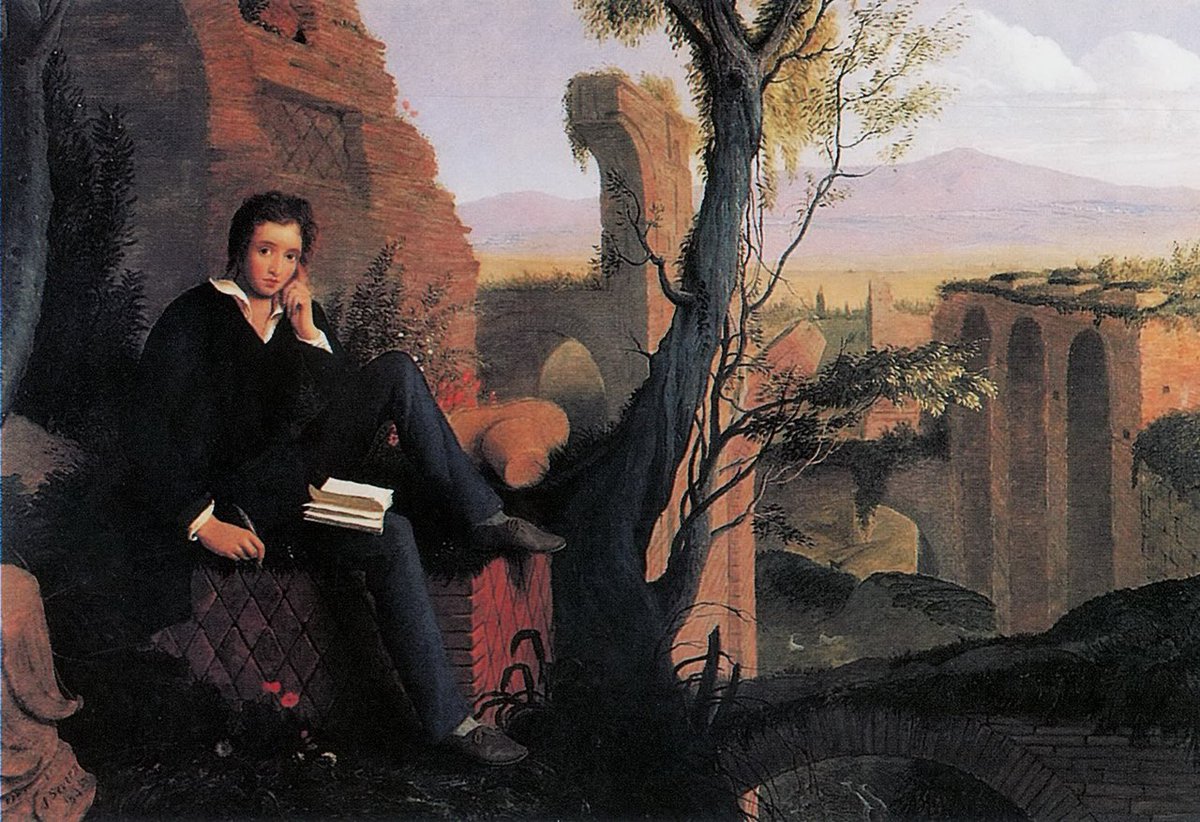

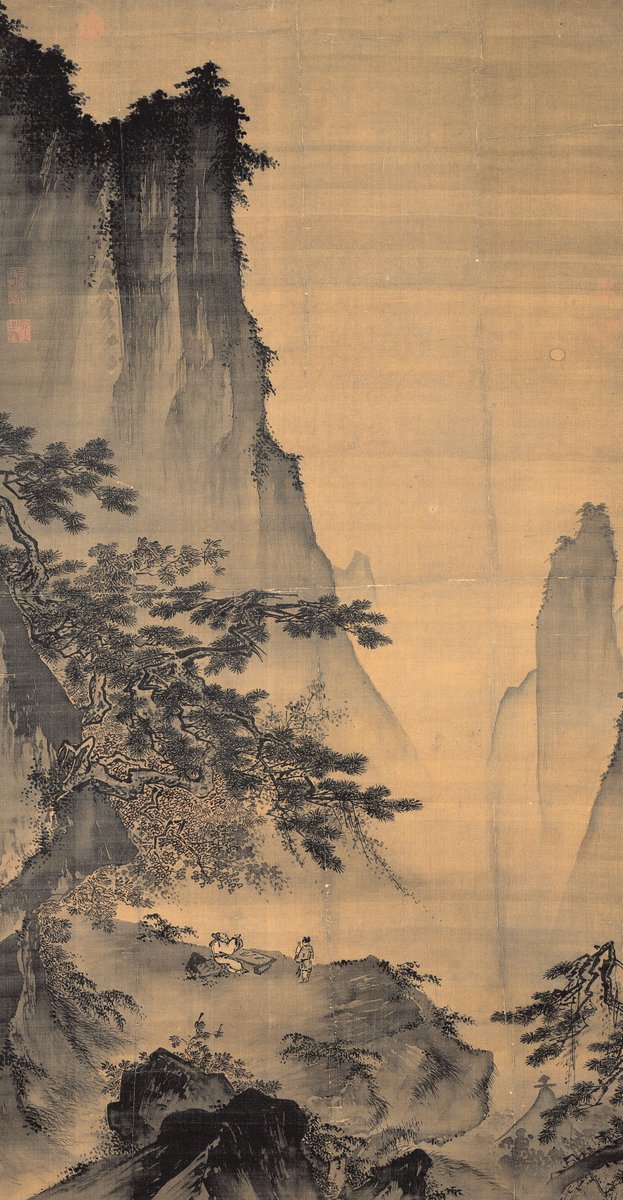

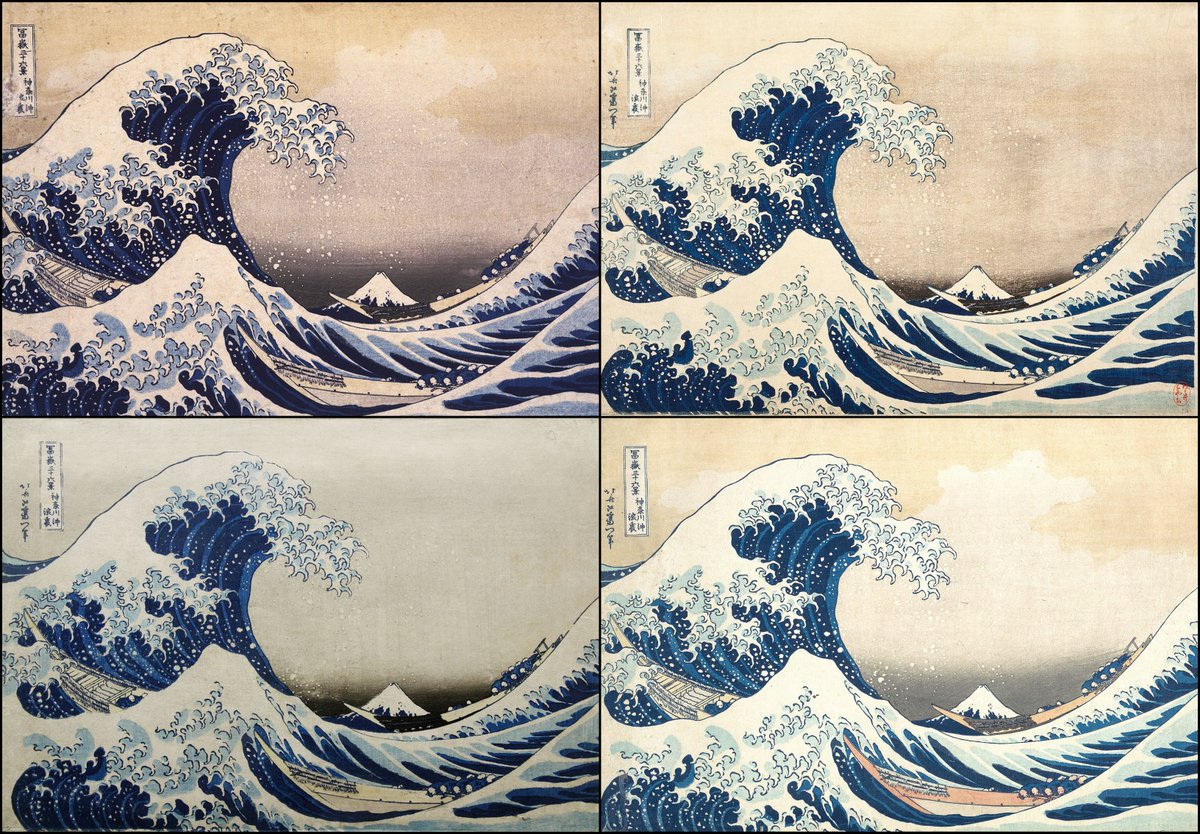

The best art is so good *because* it exceeds any specific context and becomes universal.

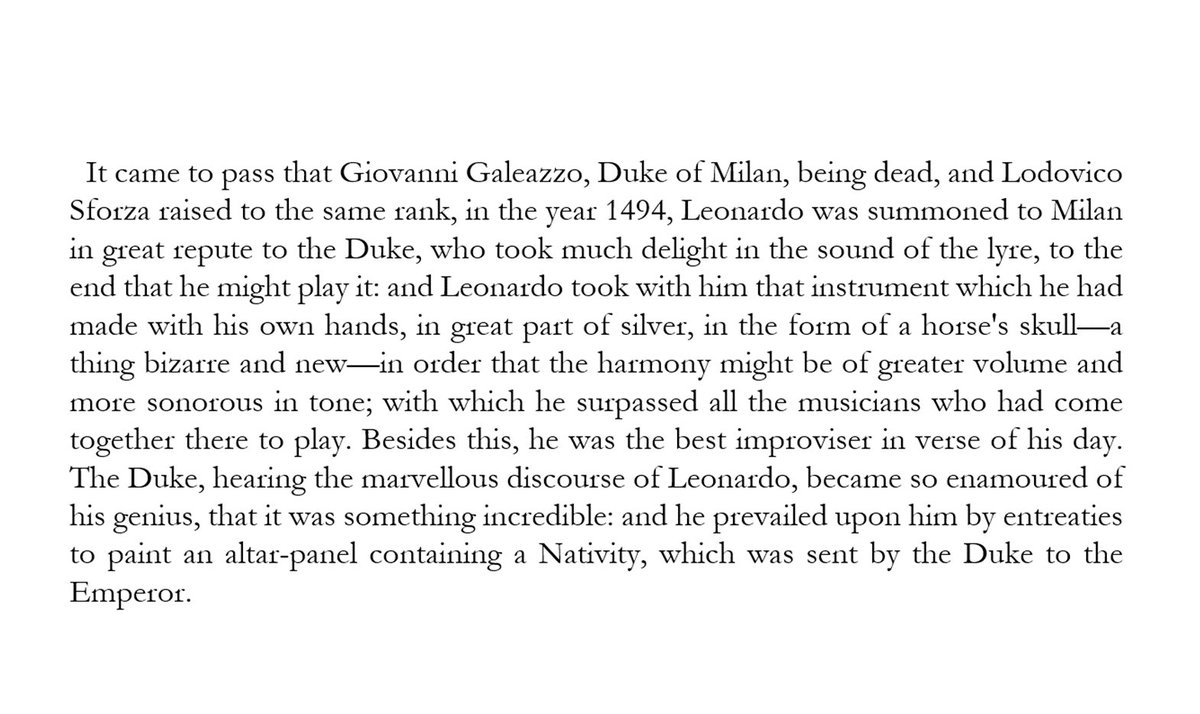

But we can't forget that, for most of history, all over the world, great art didn't just appear.

Artists needed patrons and without them much of what we now call great art wouldn't exist.

But we can't forget that, for most of history, all over the world, great art didn't just appear.

Artists needed patrons and without them much of what we now call great art wouldn't exist.

Loading suggestions...