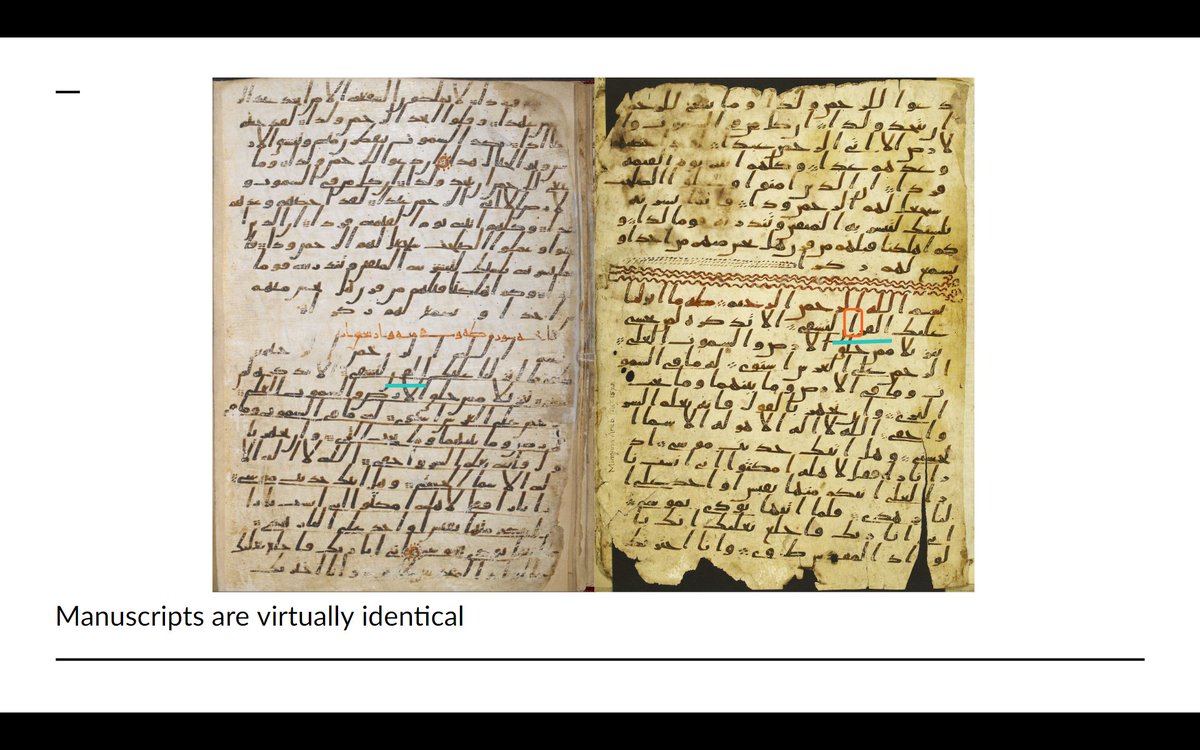

This is true not just for this page and just these two manuscripts. This is standard for any page of any 7th century manuscript: the deviations are extremely minimal.

To "intuit" this, you do need to look at a lot of manuscripts, in 2019 I tried to formalize this intuition.

To "intuit" this, you do need to look at a lot of manuscripts, in 2019 I tried to formalize this intuition.

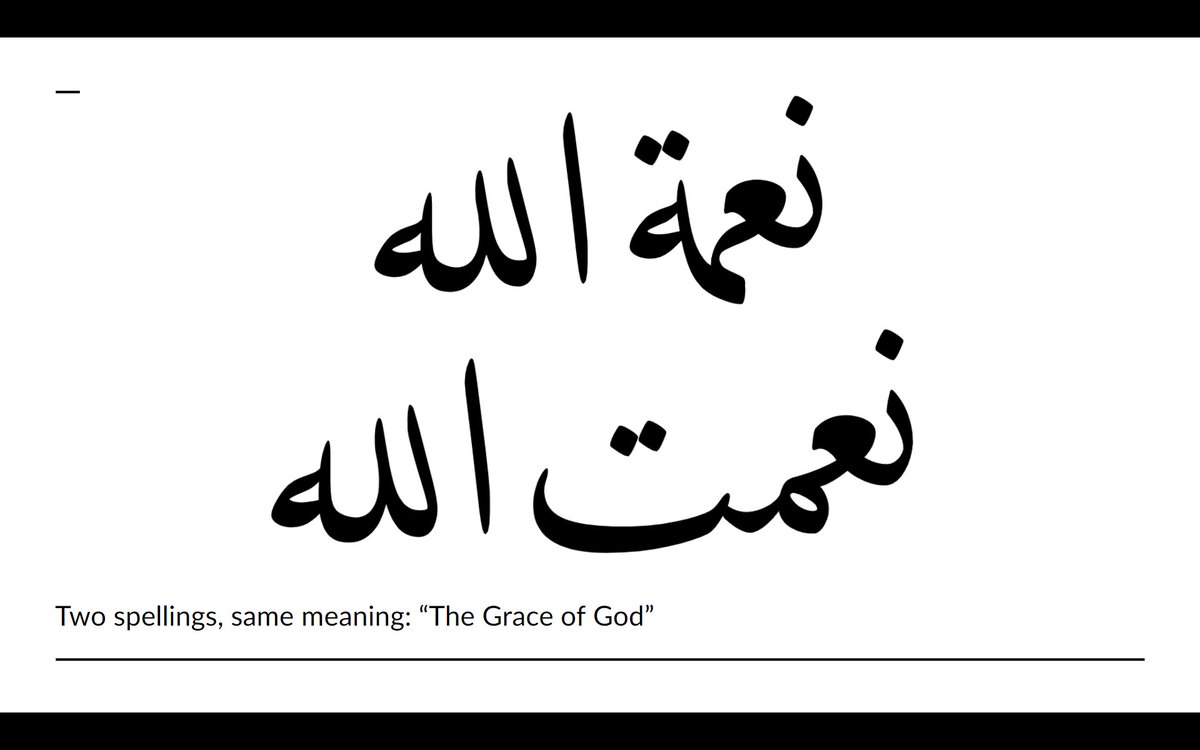

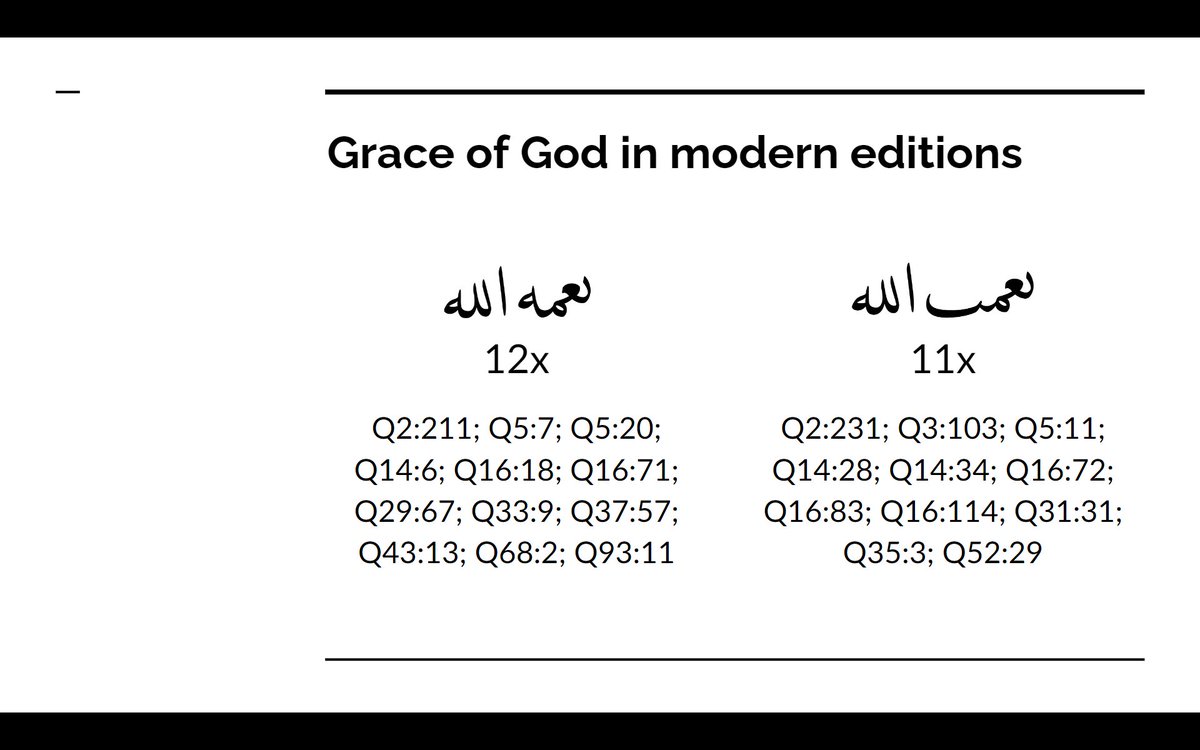

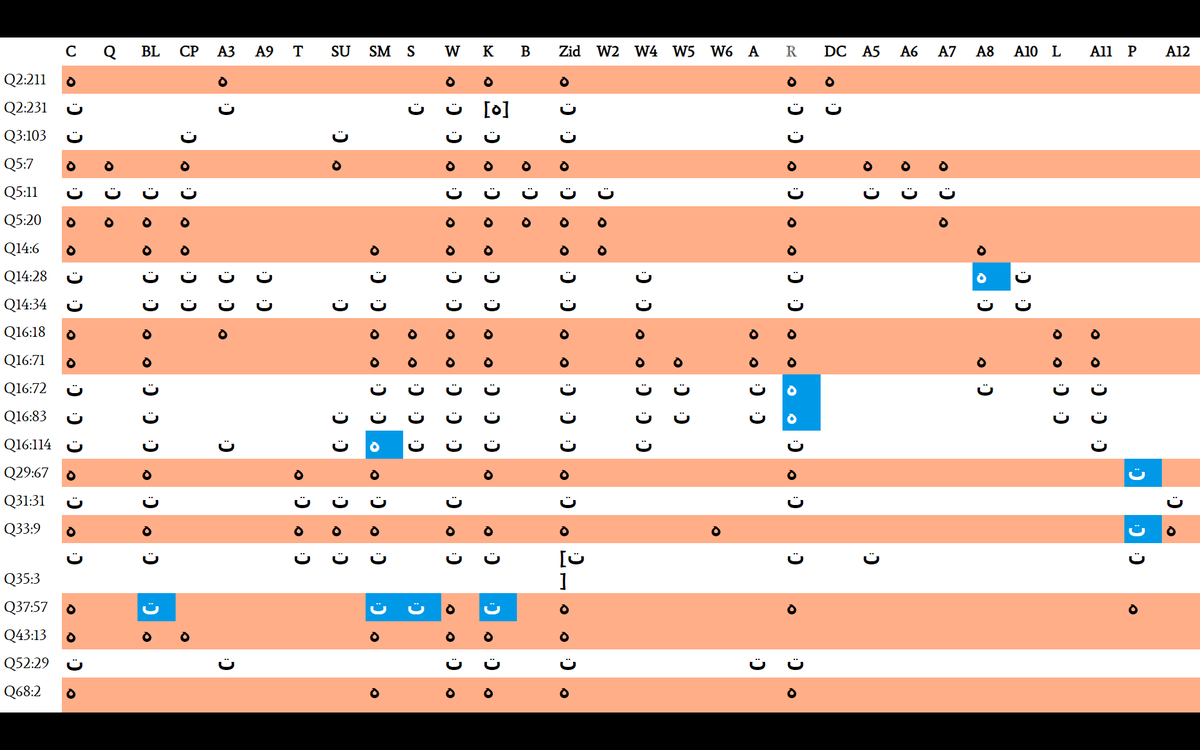

That is when I wrote my "Grace of God" article, where I show that the idiosyncratic spelling of the phrase niʿmat aḷḷāh is almost perfectly reproduced in all early manuscripts.

doi.org

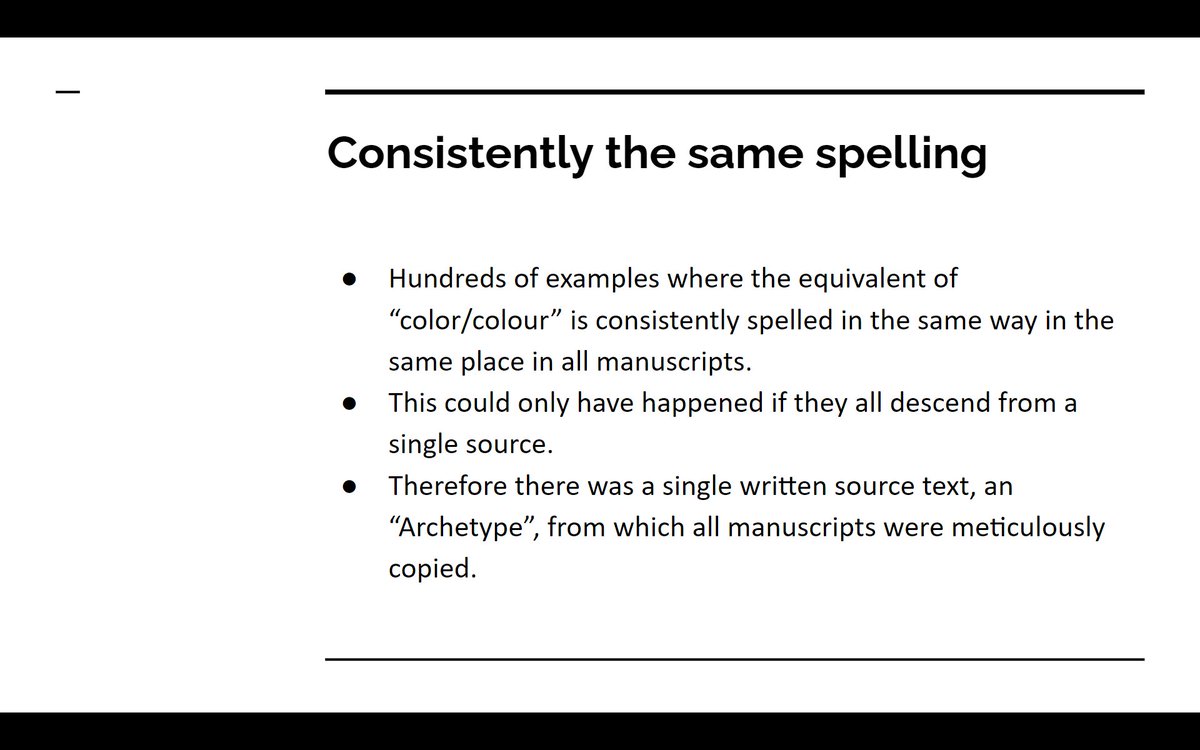

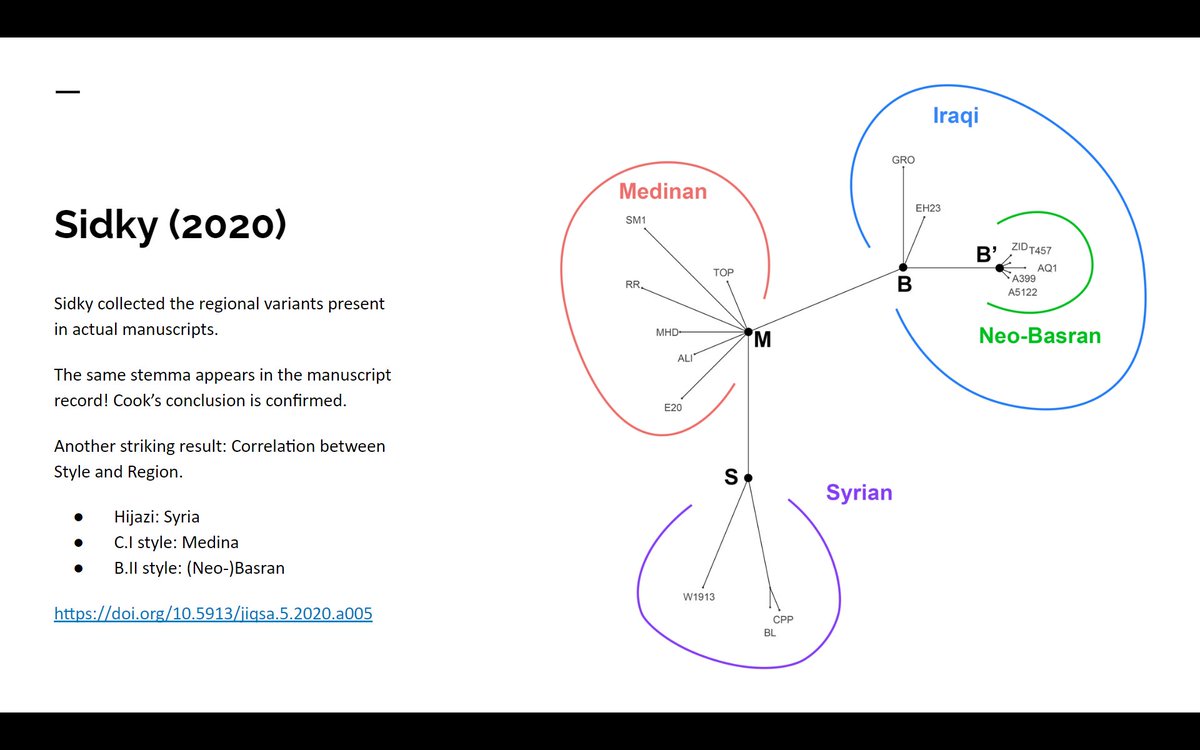

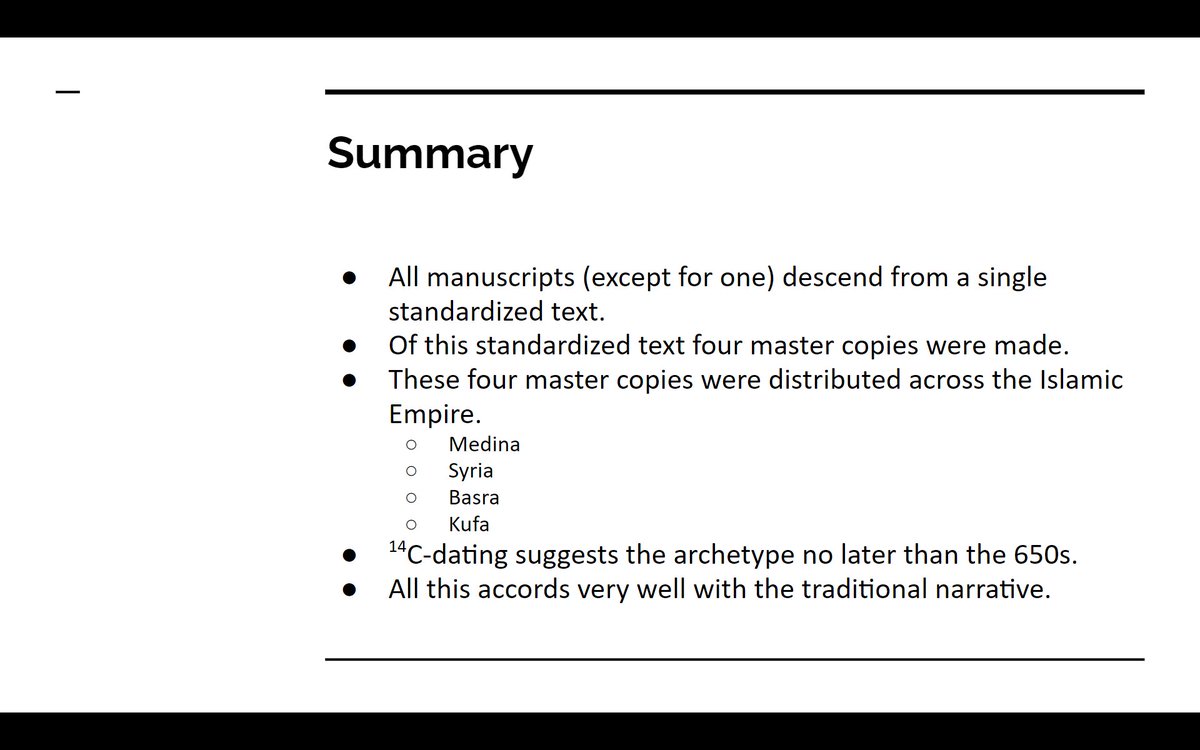

All manuscripts descend from a single written archetype.

doi.org

All manuscripts descend from a single written archetype.

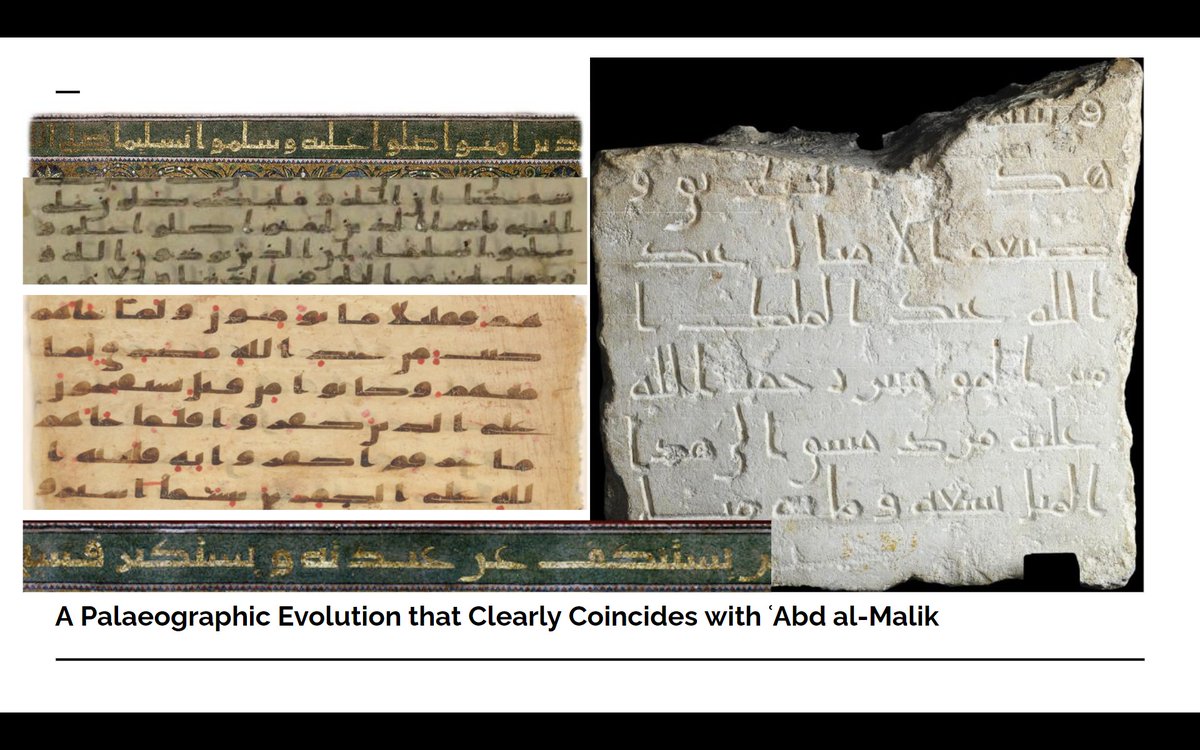

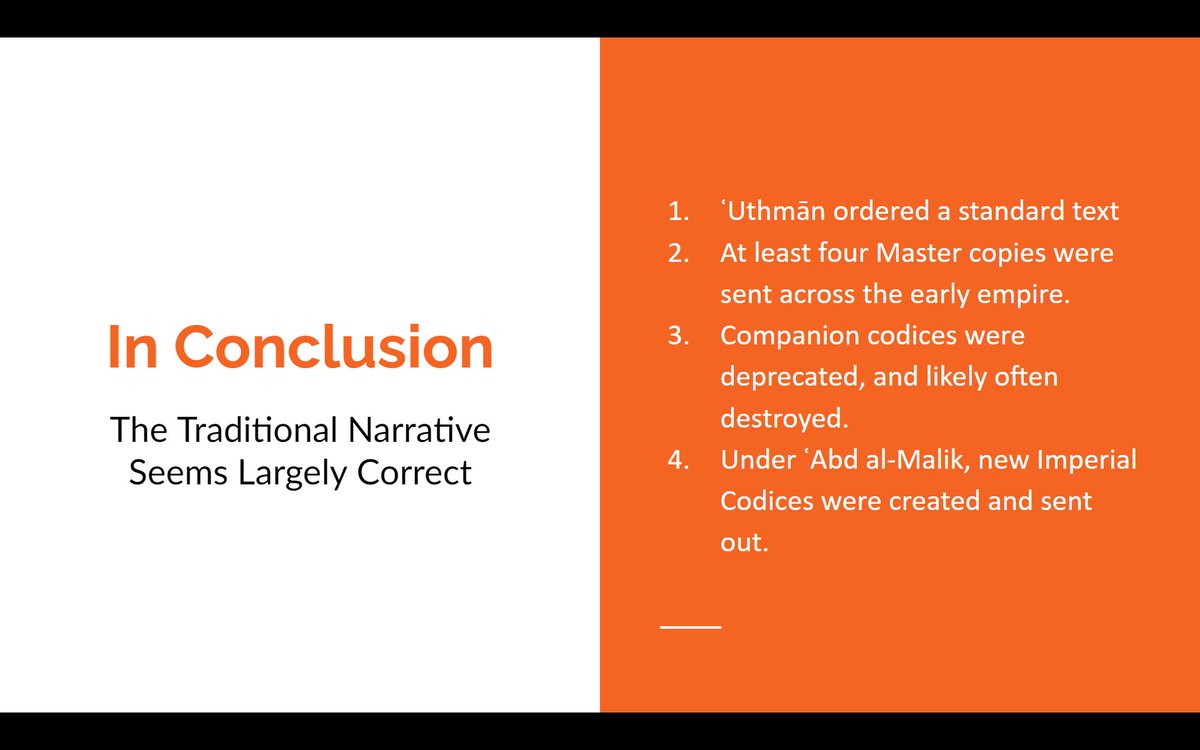

I personally do not think these two argument actually get you to ʿAbd al-Malik. At best they get you to a place where one decides the evidence is equivocal.

I don't believe the data to be equivocal though.

I don't believe the data to be equivocal though.

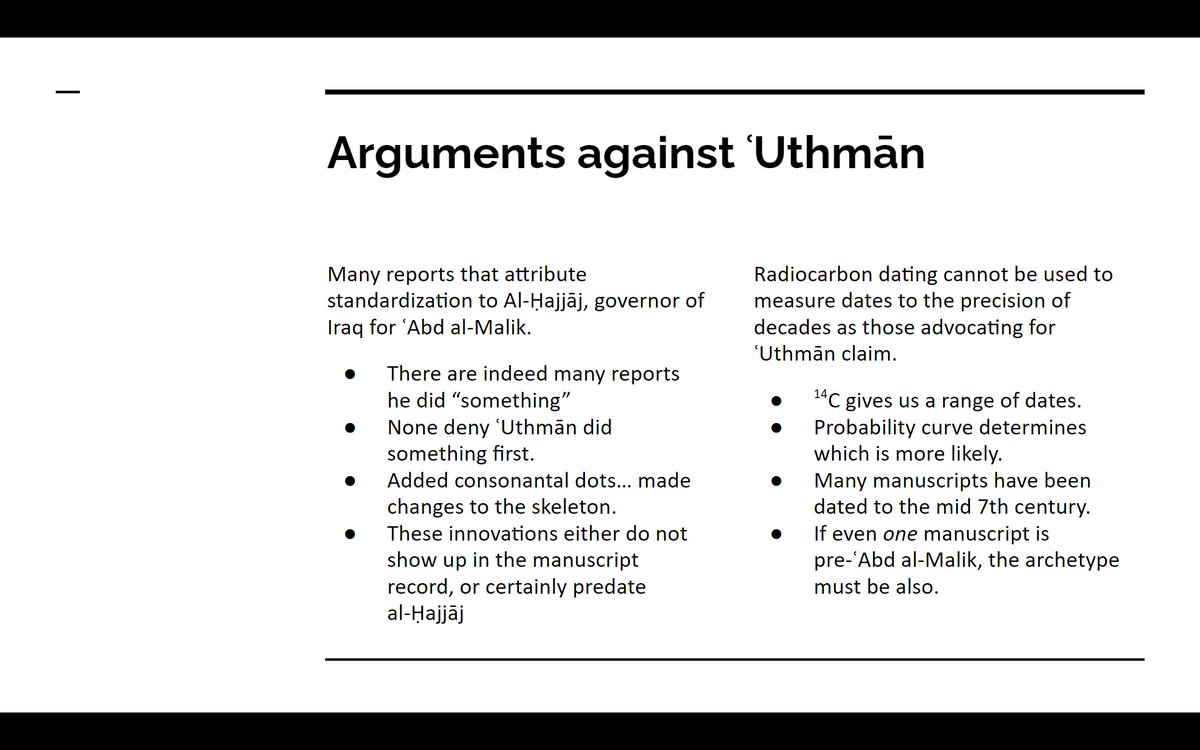

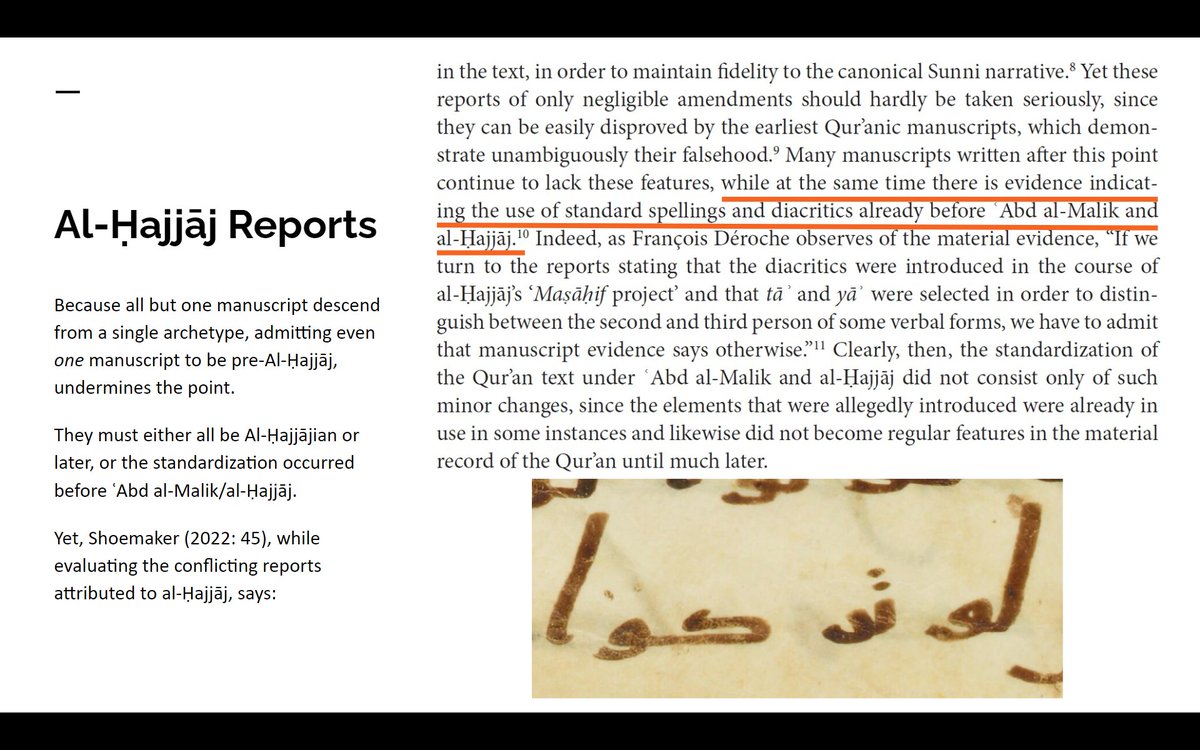

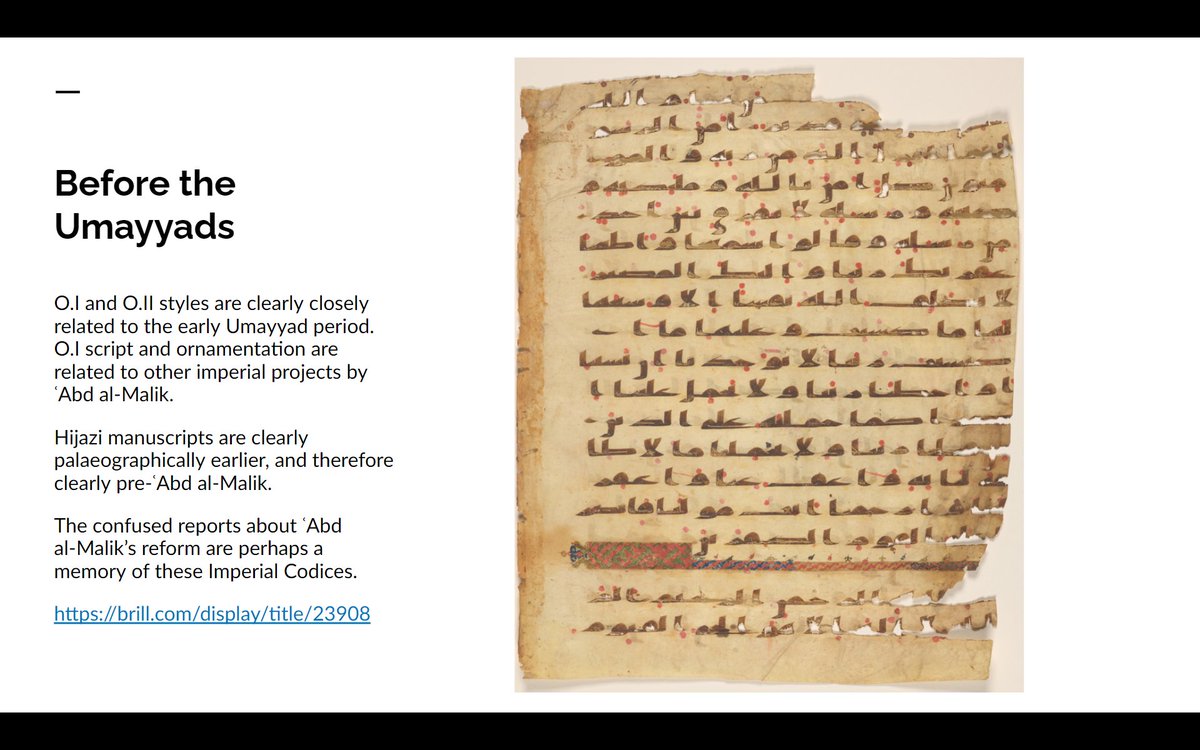

Shoemaker seems to be confused about this. He cites positively Déroche who dismissed the accuracy of the reports of what ʿAbd al-Malik did (Shoemaker imagines ʿAbd al-Malik did much more). But Déroche's argument ONLY works with the existence of pre-ʿAbd al-Malik manuscripts.

Déroche's argument:

1. ʿAbd al-Malik introduced consonantal dots.

2. We have pre-ʿAbd al-Malik manuscripts with consonantal dots.

3. Therefore ʿAbd al-Malik can't have introduced these.

Obviously you can't use that to dismiss the historicity of reports if you reject step 2.

1. ʿAbd al-Malik introduced consonantal dots.

2. We have pre-ʿAbd al-Malik manuscripts with consonantal dots.

3. Therefore ʿAbd al-Malik can't have introduced these.

Obviously you can't use that to dismiss the historicity of reports if you reject step 2.

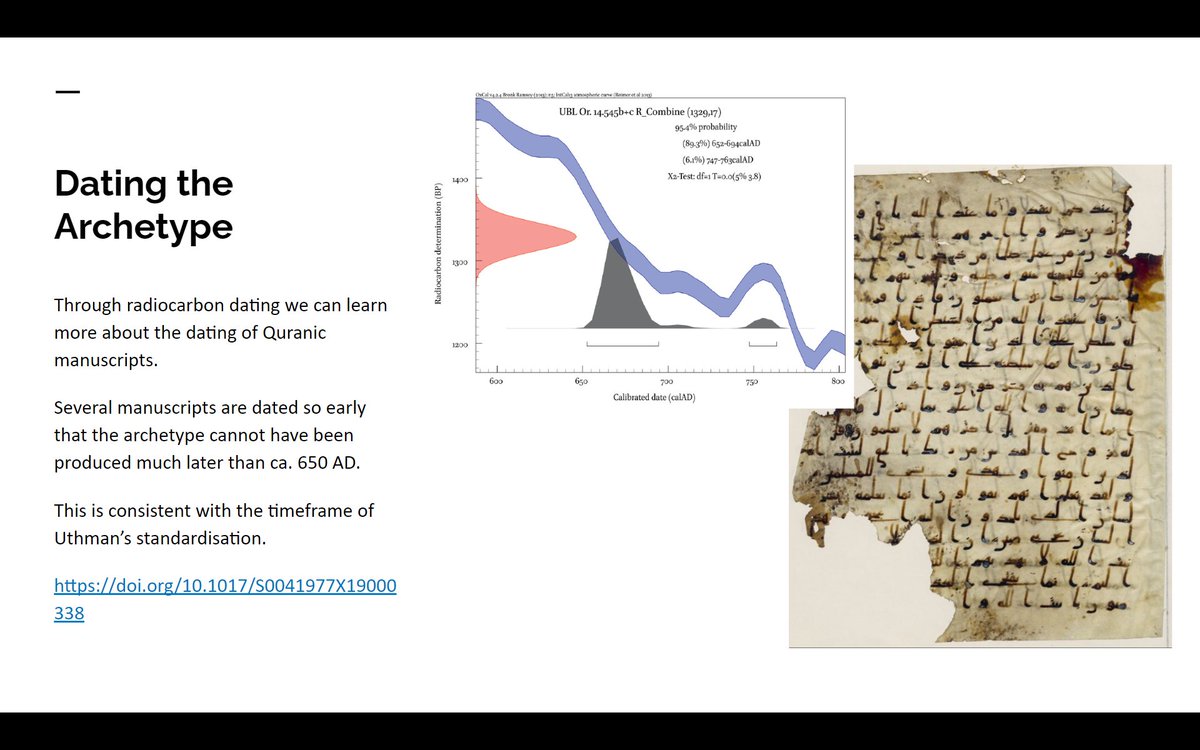

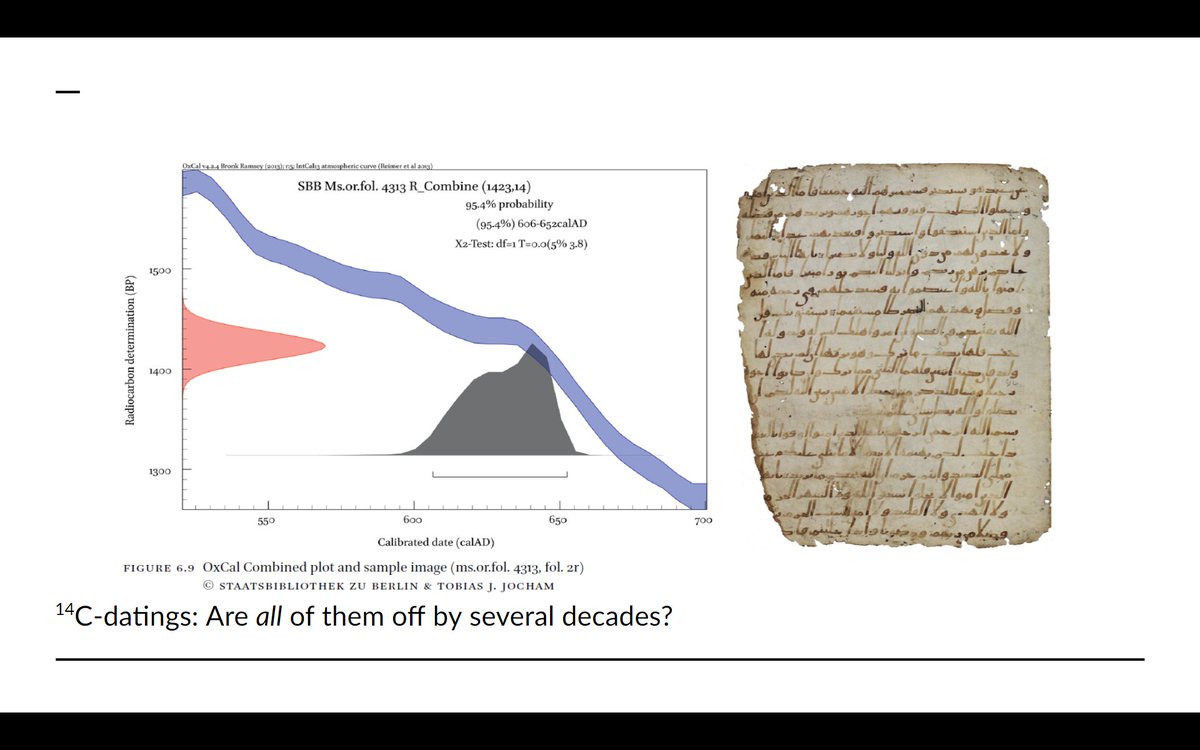

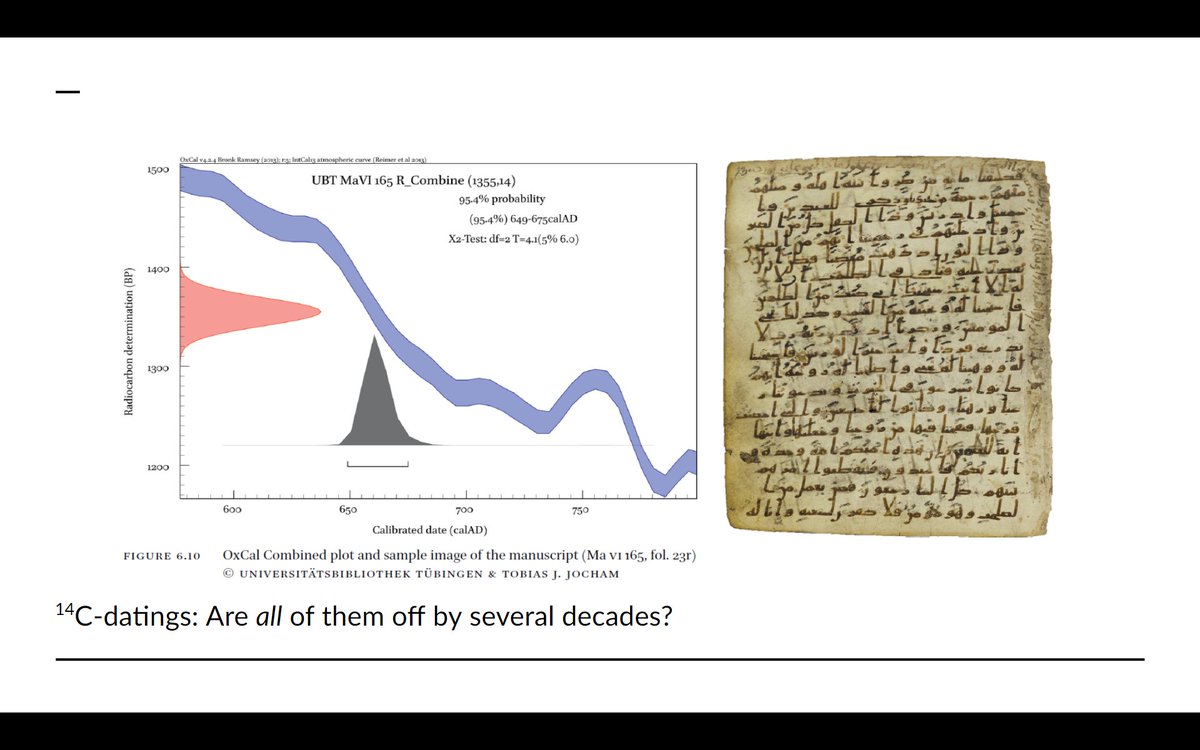

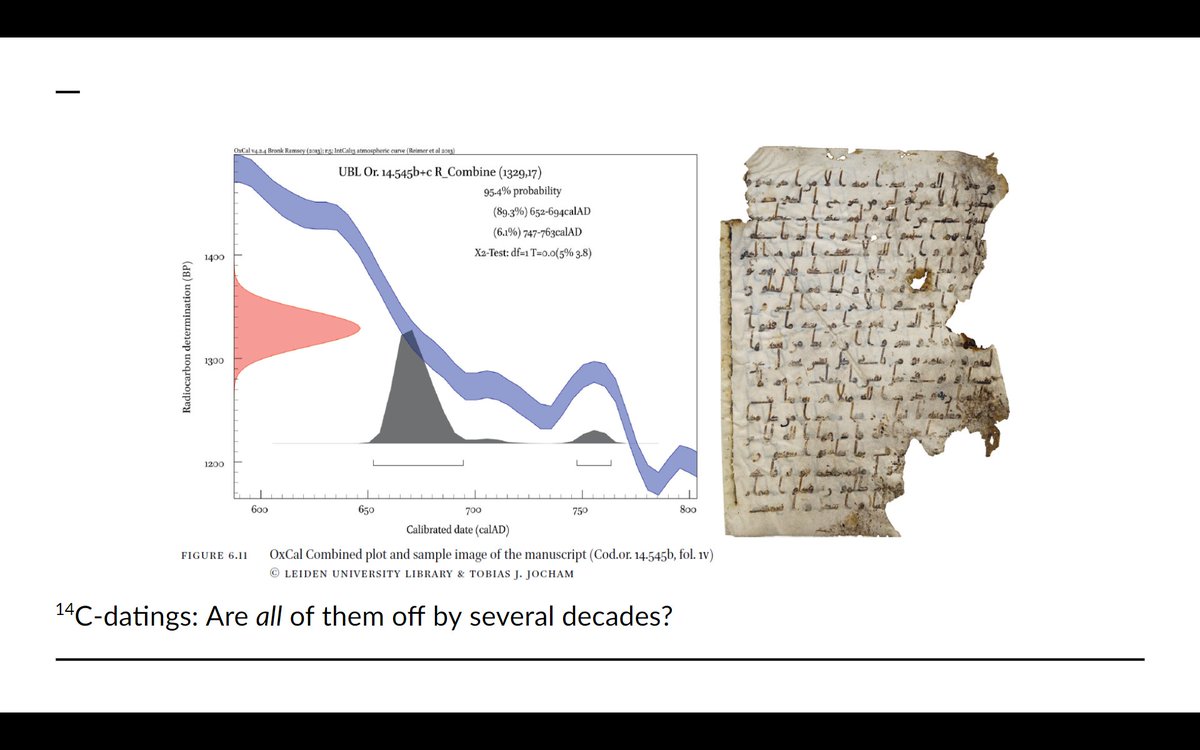

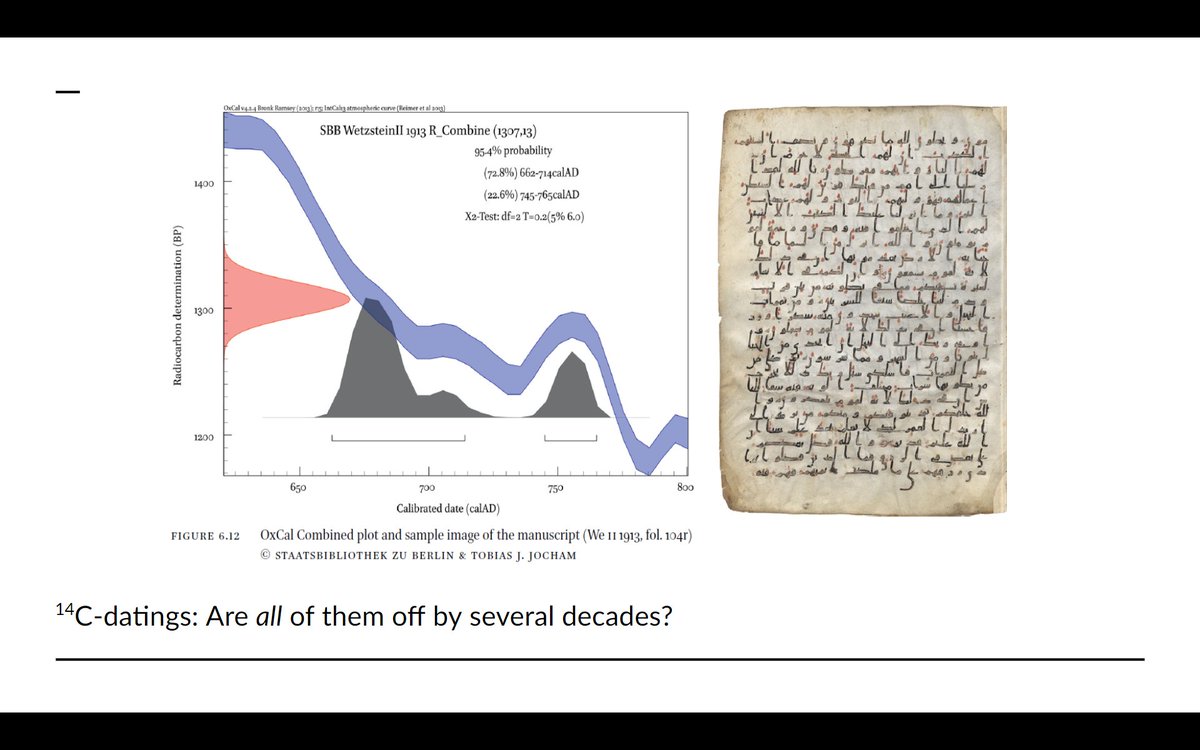

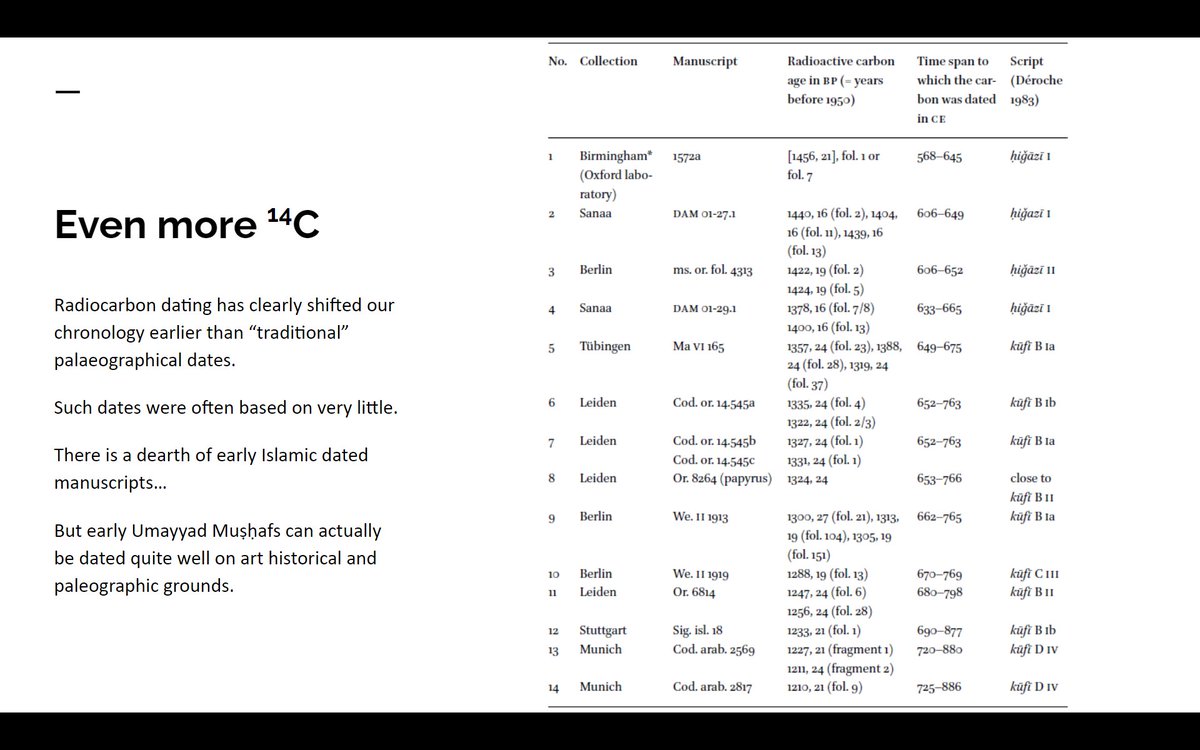

But hey, physics was broken irreparably because "Three body problem"-style aliens interfered, and we really can't trust the radiocarbon dating. Does the argument depend on that? Not at all! Déroche himself is quite skeptical of carbondating and still argues for ʿUṯmān.

If you think these kinds topics are cool, and the critical investigation into the history of the Quran and the Bible in a comparative way is worthwhile make sure to check out my friend @DrJavadTHashmi's course together with @BartEhrman.

ehrman.thrivecart.com

ehrman.thrivecart.com

Loading suggestions...