In the 15th century, England was fighting a civil war known as the Wars of the Roses, where the Houses of York and Lancaster fought for the English throne.

In 1471, the Yorkists secured a big victory by defeating the Lancastrians at the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury, leading to the deaths of King Henry VI and his son, Edward of Westminster.

In 1471, the Yorkists secured a big victory by defeating the Lancastrians at the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury, leading to the deaths of King Henry VI and his son, Edward of Westminster.

This event left the House of Lancaster without direct heirs, and the Yorkist Edward IV became the undisputed ruler of England.

He declared Lancastrian supporters like Jasper Tudor and his nephew Henry Tudor as traitors and confiscating their lands. The Tudors fled to Brittany, where Duke Francis II provided them with protection.

He declared Lancastrian supporters like Jasper Tudor and his nephew Henry Tudor as traitors and confiscating their lands. The Tudors fled to Brittany, where Duke Francis II provided them with protection.

Henry aimed to unite the warring factions by pledging to marry Elizabeth of York, the daughter of Edward IV, merging the houses of York and Lancaster.

Richard III, recognizing the threat posed by Henry, attempted to have him extradited from Brittany, but Henry escaped to France.

In 1485, rumors spread that Richard intended to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York, which threatened to unravel Henry’s support. In response, Henry gathered forces in France and prepared to invade England, setting the stage for the final confrontation between the two factions.

Richard III, recognizing the threat posed by Henry, attempted to have him extradited from Brittany, but Henry escaped to France.

In 1485, rumors spread that Richard intended to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York, which threatened to unravel Henry’s support. In response, Henry gathered forces in France and prepared to invade England, setting the stage for the final confrontation between the two factions.

Richard’s most loyal supporter was John Howard, 1st Duke of Norfolk.

Howard had served Edward IV for many years and was a veteran of significant battles, including the Battle of Towton.

Although Howard had a grudge against Edward IV for depriving him of his share of the Mowbray estate, Richard rewarded Howard’s loyalty by granting him the dukedom of Norfolk and restoring his share of the estate. This made Howard a steadfast supporter of Richard III.

Howard had served Edward IV for many years and was a veteran of significant battles, including the Battle of Towton.

Although Howard had a grudge against Edward IV for depriving him of his share of the Mowbray estate, Richard rewarded Howard’s loyalty by granting him the dukedom of Norfolk and restoring his share of the estate. This made Howard a steadfast supporter of Richard III.

Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland, also supported Richard’s rise to the throne.

Although the Percys had been loyal Lancastrians, Northumberland eventually swore allegiance to Edward IV after being imprisoned by the Yorkists.

Northumberland served the Yorkist crown in the north of England and participated in Richard’s 1482 Scottish campaign.

His support for Richard’s claim to the throne likely stemmed from the prospect of dominating the north if Richard moved south to become king.

However, after Richard's coronation, Northumberland was passed over for a key position in favor of Richard's nephew, John de la Pole, 1st Earl of Lincoln.

Although the Percys had been loyal Lancastrians, Northumberland eventually swore allegiance to Edward IV after being imprisoned by the Yorkists.

Northumberland served the Yorkist crown in the north of England and participated in Richard’s 1482 Scottish campaign.

His support for Richard’s claim to the throne likely stemmed from the prospect of dominating the north if Richard moved south to become king.

However, after Richard's coronation, Northumberland was passed over for a key position in favor of Richard's nephew, John de la Pole, 1st Earl of Lincoln.

The Lancastrians:

Henry Tudor was relatively inexperienced in warfare and unfamiliar with the land he sought to conquer. He spent his early years in Wales and then lived in Brittany and France for fourteen years.

Though slender and strong, Henry was not inclined towards battle and was more interested in commerce and finance, as noted by chroniclers like Polydore Vergil and ambassadors such as Pedro de Ayala.

Henry Tudor was relatively inexperienced in warfare and unfamiliar with the land he sought to conquer. He spent his early years in Wales and then lived in Brittany and France for fourteen years.

Though slender and strong, Henry was not inclined towards battle and was more interested in commerce and finance, as noted by chroniclers like Polydore Vergil and ambassadors such as Pedro de Ayala.

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, served as Henry’s military commander. He was a skilled and experienced warrior and had previously commanded the Lancastrian right wing at the Battle of Barnet.

However, a miscommunication led to his forces being fired upon by their own side, causing them to retreat. Oxford continued his resistance against the Yorkists from abroad, capturing St Michael's Mount in 1473 before being forced to surrender.

After escaping prison in 1484, Oxford joined Henry in France, bringing with him Sir James Blount, his former jailer. Oxford’s presence significantly boosted morale among Henry’s supporters and posed a concern for Richard III.

However, a miscommunication led to his forces being fired upon by their own side, causing them to retreat. Oxford continued his resistance against the Yorkists from abroad, capturing St Michael's Mount in 1473 before being forced to surrender.

After escaping prison in 1484, Oxford joined Henry in France, bringing with him Sir James Blount, his former jailer. Oxford’s presence significantly boosted morale among Henry’s supporters and posed a concern for Richard III.

The Stanleys:

In the early stages of the Wars of the Roses, the Stanleys of Cheshire were primarily Lancastrian supporters.

However, Sir William Stanley was a committed Yorkist, fighting at the Battle of Blore Heath in 1459 and helping suppress uprisings against Edward IV in 1471.

Lord Stanley's relationship with Richard III was strained.

His marriage to Lady Margaret, Henry Tudor’s mother, in 1472 further complicated matters, as it did not endear him to Richard. Despite these tensions, Stanley did not join Buckingham’s revolt in 1483.

Although Richard III spared Lady Margaret from execution after the failed rebellion, he confiscated her titles and transferred her estates to Stanley, intending to keep him loyal to the Yorkist cause. However, Richard’s plans to reopen a land dispute that favored the Harrington family over Stanley added to their friction.

On the eve of the Battle of Bosworth, Richard, wary of Stanley’s potential defection, took Stanley’s son, Lord Strange, as a hostage to ensure his loyalty. This move highlighted the king’s mistrust of Stanley as the conflict reached its climax.

In the early stages of the Wars of the Roses, the Stanleys of Cheshire were primarily Lancastrian supporters.

However, Sir William Stanley was a committed Yorkist, fighting at the Battle of Blore Heath in 1459 and helping suppress uprisings against Edward IV in 1471.

Lord Stanley's relationship with Richard III was strained.

His marriage to Lady Margaret, Henry Tudor’s mother, in 1472 further complicated matters, as it did not endear him to Richard. Despite these tensions, Stanley did not join Buckingham’s revolt in 1483.

Although Richard III spared Lady Margaret from execution after the failed rebellion, he confiscated her titles and transferred her estates to Stanley, intending to keep him loyal to the Yorkist cause. However, Richard’s plans to reopen a land dispute that favored the Harrington family over Stanley added to their friction.

On the eve of the Battle of Bosworth, Richard, wary of Stanley’s potential defection, took Stanley’s son, Lord Strange, as a hostage to ensure his loyalty. This move highlighted the king’s mistrust of Stanley as the conflict reached its climax.

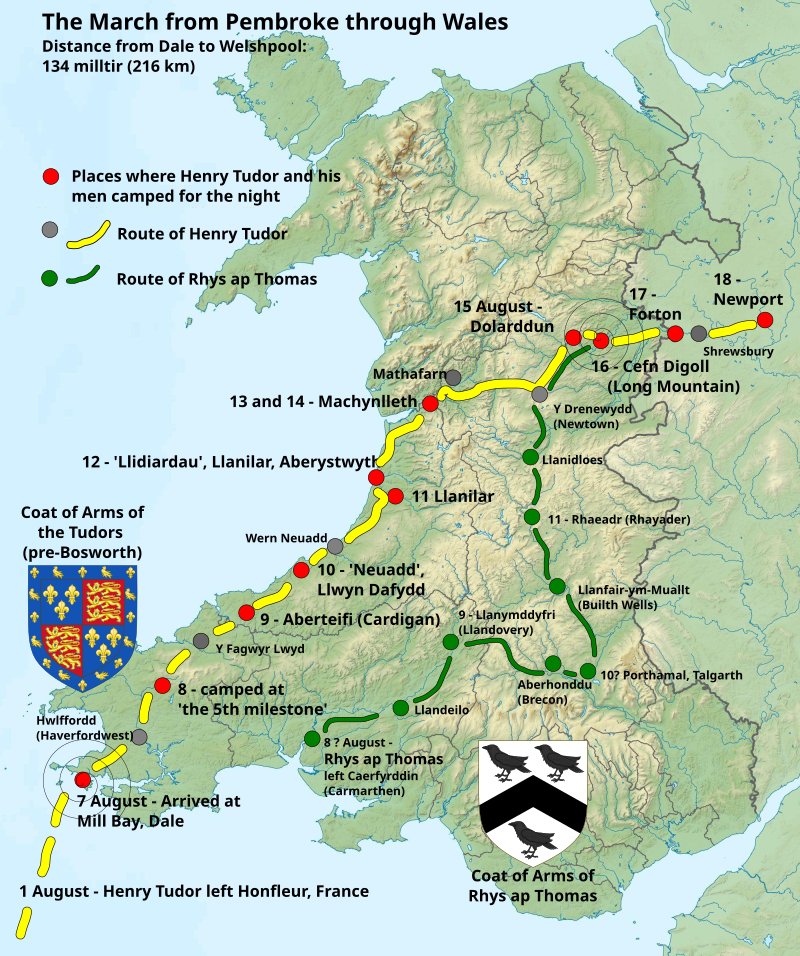

Henry Tudor's initial force consisted of English and Welsh exiles, along with mercenaries provided by Charles VIII of France.

They crossed the English Channel on 1 August 1485, landing in Wales at Mill Bay on 7 August. Despite a muted local response, Henry's forces gradually grew as they marched inland. Key defections, including Rhys ap Thomas, bolstered his army. By mid-August, after recruiting more Welshmen, Henry's forces crossed into England, aiming for Shrewsbury.

They crossed the English Channel on 1 August 1485, landing in Wales at Mill Bay on 7 August. Despite a muted local response, Henry's forces gradually grew as they marched inland. Key defections, including Rhys ap Thomas, bolstered his army. By mid-August, after recruiting more Welshmen, Henry's forces crossed into England, aiming for Shrewsbury.

The Long March:

On 22 June, Richard III became aware of Henry Tudor’s impending invasion and ordered his lords to maintain a state of high readiness.

When Henry landed in England on 11 August, it took three to four days for Richard’s messengers to alert his lords and mobilize the Yorkist army. By 16 August, Richard’s forces began to assemble, with Norfolk departing for the assembly point at Leicester that night.

The city of York, a stronghold of Richard’s family, sought instructions from the king and sent 80 men to join him after receiving a response three days later. Meanwhile, Northumberland, whose lands were furthest from the capital, gathered his forces and also headed to Leicester.

On 22 June, Richard III became aware of Henry Tudor’s impending invasion and ordered his lords to maintain a state of high readiness.

When Henry landed in England on 11 August, it took three to four days for Richard’s messengers to alert his lords and mobilize the Yorkist army. By 16 August, Richard’s forces began to assemble, with Norfolk departing for the assembly point at Leicester that night.

The city of York, a stronghold of Richard’s family, sought instructions from the king and sent 80 men to join him after receiving a response three days later. Meanwhile, Northumberland, whose lands were furthest from the capital, gathered his forces and also headed to Leicester.

London was Henry’s ultimate goal, he did not march directly towards the city however.

After resting in Shrewsbury, Henry’s forces moved eastwards, gathering English allies, including deserters from Richard’s army, along the way.

Despite these reinforcements, Henry’s army remained significantly smaller than Richard’s. Henry advanced slowly through Staffordshire, hoping to recruit more men before the inevitable confrontation with Richard.

Henry had been in communication with the Stanleys well before his landing in England, and the Stanleys mobilized their forces upon hearing of his arrival. They positioned themselves ahead of Henry’s march, meeting him in secret twice as he moved through Staffordshire.

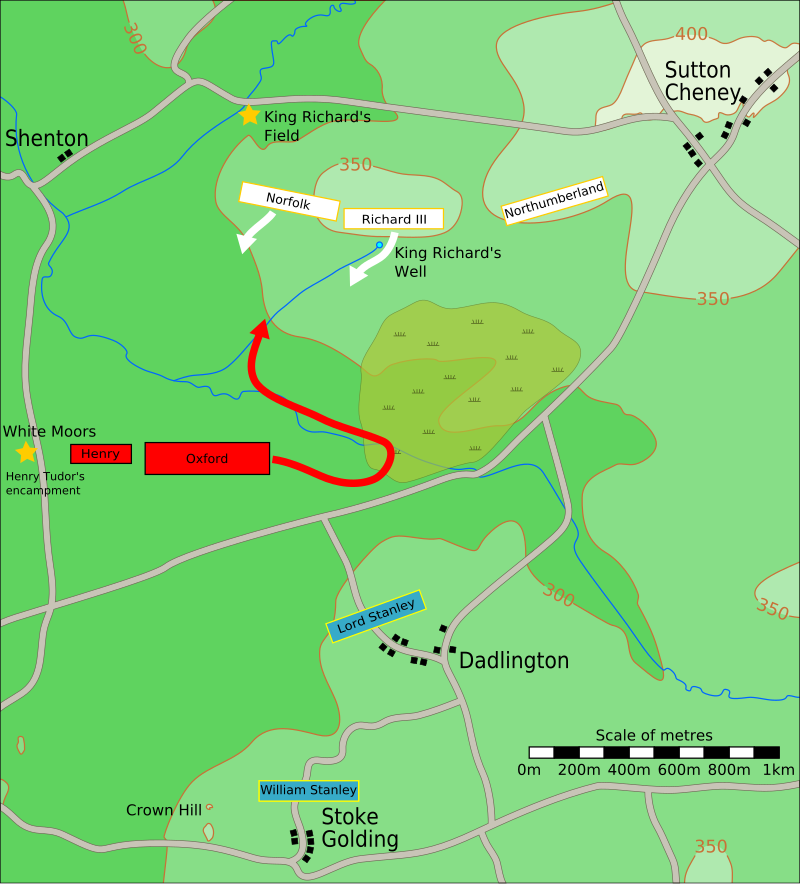

During their second meeting at Atherstone in Warwickshire, they discussed plans to confront Richard, who was reported to be nearby. On 21 August, the Stanleys set up camp on the slopes of a hill north of Dadlington, while Henry positioned his forces at White Moors, northwest of the Stanleys' camp.

After resting in Shrewsbury, Henry’s forces moved eastwards, gathering English allies, including deserters from Richard’s army, along the way.

Despite these reinforcements, Henry’s army remained significantly smaller than Richard’s. Henry advanced slowly through Staffordshire, hoping to recruit more men before the inevitable confrontation with Richard.

Henry had been in communication with the Stanleys well before his landing in England, and the Stanleys mobilized their forces upon hearing of his arrival. They positioned themselves ahead of Henry’s march, meeting him in secret twice as he moved through Staffordshire.

During their second meeting at Atherstone in Warwickshire, they discussed plans to confront Richard, who was reported to be nearby. On 21 August, the Stanleys set up camp on the slopes of a hill north of Dadlington, while Henry positioned his forces at White Moors, northwest of the Stanleys' camp.

The Battle:

The Yorkist army, led by Richard III, deployed on Ambion Hill, with forces ranging between 7,500 and 12,000 men.

Norfolk commanded the right flank, protecting artillery and archers, while Richard's infantry held the center, and Northumberland's men, many mounted, guarded the left. Richard had a clear view of the battlefield, where the Stanleys and their forces, and Henry Tudor's army, could be seen.

The Yorkist army, led by Richard III, deployed on Ambion Hill, with forces ranging between 7,500 and 12,000 men.

Norfolk commanded the right flank, protecting artillery and archers, while Richard's infantry held the center, and Northumberland's men, many mounted, guarded the left. Richard had a clear view of the battlefield, where the Stanleys and their forces, and Henry Tudor's army, could be seen.

Henry's forces, estimated at 5,000 to 8,000 men, were bolstered by recruits from Wales and English border counties, including deserters from Richard's army.

The core of Henry's force included 1,800 French mercenaries. As Henry's army advanced, they faced harassment from Richard's cannon. Henry, lacking military experience, entrusted command to Oxford, who kept the army in a tight formation to avoid being enveloped by Richard's larger forces.

The core of Henry's force included 1,800 French mercenaries. As Henry's army advanced, they faced harassment from Richard's cannon. Henry, lacking military experience, entrusted command to Oxford, who kept the army in a tight formation to avoid being enveloped by Richard's larger forces.

The battle began with Norfolk's forces advancing, but they were held off by Oxford's men, leading to several of Norfolk's troops fleeing.

Richard called for Northumberland's assistance, but his troops did not move, likely due to the difficulty of maneuvering on the narrow ridge of Ambion Hill.

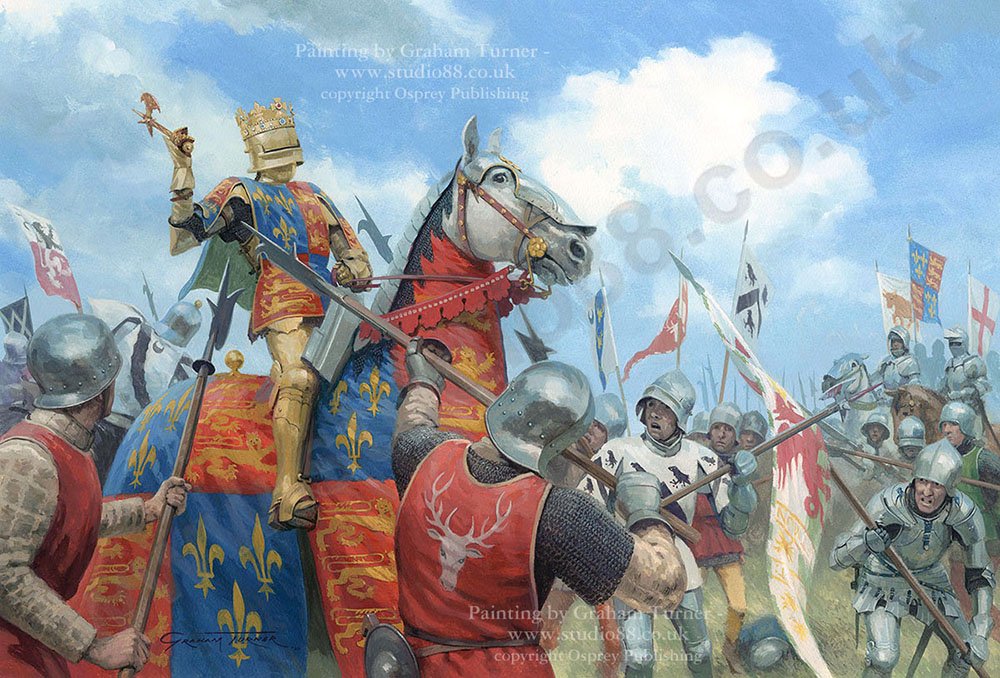

Richard then led a direct charge towards Henry, aiming to end the battle by killing him. Richard's attack was fierce, but Henry's forces, with the aid of Stanley's men, eventually surrounded and overwhelmed Richard.

Richard called for Northumberland's assistance, but his troops did not move, likely due to the difficulty of maneuvering on the narrow ridge of Ambion Hill.

Richard then led a direct charge towards Henry, aiming to end the battle by killing him. Richard's attack was fierce, but Henry's forces, with the aid of Stanley's men, eventually surrounded and overwhelmed Richard.

In the final moments, Richard, now unhorsed and separated from his main force, continued to fight bravely, refusing to retreat.

He was ultimately killed in the thick of battle, possibly by a Welshman wielding a halberd. His death led to the disintegration of the Yorkist forces, with Northumberland's men fleeing and Norfolk being killed in combat.

Richard's demise marked the end of the battle and the conclusion of his reign.

He was ultimately killed in the thick of battle, possibly by a Welshman wielding a halberd. His death led to the disintegration of the Yorkist forces, with Northumberland's men fleeing and Norfolk being killed in combat.

Richard's demise marked the end of the battle and the conclusion of his reign.

After the battle, Henry Tudor claimed the English crown by right of conquest, despite his distant Lancastrian lineage.

Richard III's crown was reportedly found and presented to Henry, who was proclaimed king near Stoke Golding.

Henry Tudor would become King Henry VII of England, ushering in the Tudor Dynasty, and a bloody end to the legendary Plantagenets.

Richard III's crown was reportedly found and presented to Henry, who was proclaimed king near Stoke Golding.

Henry Tudor would become King Henry VII of England, ushering in the Tudor Dynasty, and a bloody end to the legendary Plantagenets.

Loading suggestions...