1) I'm not sure how to make people remember or care that 15 years ago the United States invaded Iraq, setting off a war that continues to this day, with several hundred thousand Iraqis dead, millions turned into refugees. I covered the invasion for the New York Times Magazine.

4) Laurent was already a legend among photojournalists, and since the Iraq invasion he's continued to do amazing work in Syria (among other warzones). But that's another story for another day.

8) From Safwan, it was about 45 kilometers to Basra. Soldiers told us (a group of about a dozen unembedded journalists who had managed to drive into Iraq) that the road was clear to Basra. So we headed down the road and nearly got killed.

9) We started driving to Basra, thinking U.S. forces were ahead or anti-Saddam forces had taken control (like in 1990-91). No. Laurent was the lead vehicle and he was the first to notice the Iraqi soldiers at the side of the road trying to surrender to us. That wasn't good.

10) We were heading into territory still held by Saddam's forces (some trying to surrender, but others not). We all did quick U-turns and sped back to Safwan. Thankfully we didn't get shot by jumpy U.S. troops as we returned (that happened to other journalists a day or so later).

14) The night of March 20, we slept in our cars along the road, not far from the prisoners. For the next three weeks, until reaching Baghdad, that's where I slept, in my car. I heard, overhead, the whine of drones. There was the sound of machine gun fire, but not too close.

15) Because we were just a few miles from Kuwait, my Kuwaiti cell phone still worked. I got a call in the evening. It was Hertz in Kuwait City, wanting to know when I would return my SUV. I told them it would be a while. They reminded me that I wasn't allowed to take it to Iraq.

16) March 21, 2003, 15 years ago today, was odd. We (the unembedded journalists, about six or seven vehicles of us, now banded together) realized we wouldn't be getting to Basra soon -- it was still held by Saddam's forces. Wait it out, or head north to Baghdad?

17) We had learned, from the previous day's mistake of driving on our own toward Iraqi frontlines outside Basra, that we had to travel with U.S. military, otherwise we might get captured or shot by Iraqis, or shot by Americans, thinking we were Iraqis.

18) I forget the details, but we inched around toward Zubayr, a Basra suburb, behind U.S. forces. At one point, we came across a unit where photographer Kuni Takahashi (aka @kuniphoto) was unhappily embedded with a unit whose commander wouldn't let him send out his photos.

21) By the end of the day we realized Basra wasn't going to fall quickly. We could wait it out or head north to Baghdad. I had not thought of going to Baghdad -- my assignment was to cover what I and my editors thought would be the quick & happy liberation of Basra. Ha, I know.

23) One thing I don't like in American war reporting -- it is too often about us (our soldiers, our reporters). It will be hard to escape that vise in this thread; my contact w/Iraqis was limited. The grim truth is that a lot of Iraqis I saw were corpses. But they have stories.

26) This day 15 years ago, I drove on highway 1 toward Nasiriya, skipping from one military convoy to another, whichever moved quickest. This was risky; convoys that didn't recognize us would aim their weapons as we neared. We sometimes stopped, got out to show we weren't Iraqis.

27) At dusk, we stopped to spend the night with a Marine unit on the roadside. Apache & Blackhawk helicopters flew overhead. Marines were shocked I was in a warzone without a gun. "You're not carrying any frigging weapons?" one of them asked. "Not even a nine-millimeter?"

30) War is a set of collisions. People you've never met or imagined are suddenly at the center of your life. They save you, they try to kill you, they do or say something you can't forget -- and then they're gone (or maybe not). Lt. Tim McLaughlin was one of these people.

31) McLaughlin was a tank commander in the Third Battalion, Fourth Marine Regiment (aka 3/4), and exactly 15 years ago to this day, 3/4 was a few dozen miles from me, capturing the Basra airport. His battalion was a battering ram of the invasion. Our paths would soon cross.

34) As I fell asleep along Highway 1 in my car that night, shivering in my sleeping bag (it was still cold), McLaughlin was mopping up at the Basra airport. In a few days, I would unexpectedly join his battalion's violent march to Baghdad, a collision that changed everyone.

37) Here's some of what he wrote: "It was like climbing a chimney with smoke filling in from top to bottom. I stopped, finally realizing that I was completely alone in the largest office building in the world. I could barely see my hand in front of me."

38) The only illumination inside was from blinking emergency lights. The only thing he heard was a recording that said, "There has been an emergency. Please exit the building immediately." When he got back outside, a corporal asked him, "What do we do now, sir?"

39) McLaughlin knew what to do. He transferred to a combat unit in Twentynine Palms, California. When it deployed to Kuwait in 2003, he made sure to bring a copy of the constitution that was in his Pentagon office on 9/11, and an American flag a friend gave him after the attack.

43) We made our way to the western outskirts of Nasiriya, to a temporary bridge the Marines built over the Euphrates. The main road through Nasiriya was blocked due to fighting (the next day, Private Jessica Lynch, in a convoy that took a wrong turn, was captured there).

44) There was a traffic jam at the bridge -- just one narrow lane, if memory serves, behind which an invading army waited to cross. Our mini-convoy of six or seven SUVs of journalists was told to wait. We had the lowest priority to cross. It could be hours, it could be days.

45) In warzones, journalists depend on each other to stay safe. We travel together for safety, we exchange information with each other to stay safe, we share our food and water and risk our lives for each other. Sounds cliched, yes, but it's true. However...

46) ...rival journalists can be unkind with each other, too. During the Bosnia war, which I covered for the Washington Post, I nearly got in a fight with a New York Times reporter -- over who would sleep on the bed and who would sleep on the floor of a room we shared in Pale.

47) Covering a war involves all kinds of headaches, some inane. At the Nasiriya bridge, a TV journalist embedded with a passing unit told an officer, "These guys are not embedded. They're not supposed to be here." He was trying to get us kicked out of Iraq. We were competition.

48) Our status was indeed uncertain. We were not supposed to be in Iraq -- we had snuck in, after all. There was a hotel filled with journalists in Kuwait City whom the U.S. military wouldn't let into Iraq. At any moment, any officer could give an order and we'd be done.

49) But war is chaos and the military is not a monolith. On the ground, what Donald Rumsfeld had decreed was less important for us than what the control officer at the bridge outside Nasiriya was feeling. And he didn't mind us being in Iraq. Our jealous colleague was ignored.

50) Night fell. The only light came from tracer bullets and flares the U.S. dropped over Nasiriya. My eyes burned from diesel exhaust and dust. I fell asleep in my car. Hours later, in the middle of the night, we got the order -- wake up, it's your turn, drive over the bridge.

53) I took these pictures 15 years ago today. What has happened to these young men who are no longer so young? I know what's happened to me -- I am doing fine, I am the fortunate American. But these men whose lives collided with mine for a moment 15 years ago, are they alive?

54) It's a measure of the chaos inflicted on Iraq that the possibilities are mostly terrible. Were they arrested? Joined the insurgency? Get injured/tortured/killed? Their mothers, fathers, children, sisters -- were they harmed? Did they flee the country? Are they alive?

56) The convoy stopped for a bit, and suddenly Marines rushed out of their Humvees and APCs and hit the ground, spread-eagled; their weapons were pointing toward us. An ambush was about to happen, or so they thought. We rushed to get out of their line of fire.

57) After almost getting captured/killed outside Basra, we realized this was unlike any war we had covered. There were no frontlines behind which we were safe. U.S. troops were rushing to Baghdad in unconnected convoys, not bothering to secure their flanks or even the rear.

58) At this point, occupying Iraq was not the objective (though that would come soon enough). Getting to Baghdad & cutting off the head of the regime was the goal right now. Until we got to Baghdad, if we got to Baghdad, there would be no security or rest. Everything was hostile.

61) I was uneasy. The journalists I was traveling with were mostly photographers -- war photographers. I had covered wars but as a writer I could hang back a bit, and was glad for that. Photographers had to be where the bullets were flying. Now, where they went, I was going.

64) We drove into a minor sandstorm (more on sandstorms later). Near dusk, with impaired visibility, we literally bumped into 3/4. We needed to stop for the night, but also needed to attach ourselves to one battalion and stay with it, rather than skipping from one to the other.

65) Several journalists were embedded with 3/4 and unlike the TV guy at the bridge who tried to get us kicked out of Iraq, these were great & generous colleagues -- Simon Robinson, Robert Nickelsberg, John Koopman. They said 3/4 was going to Baghdad and we should try to follow.

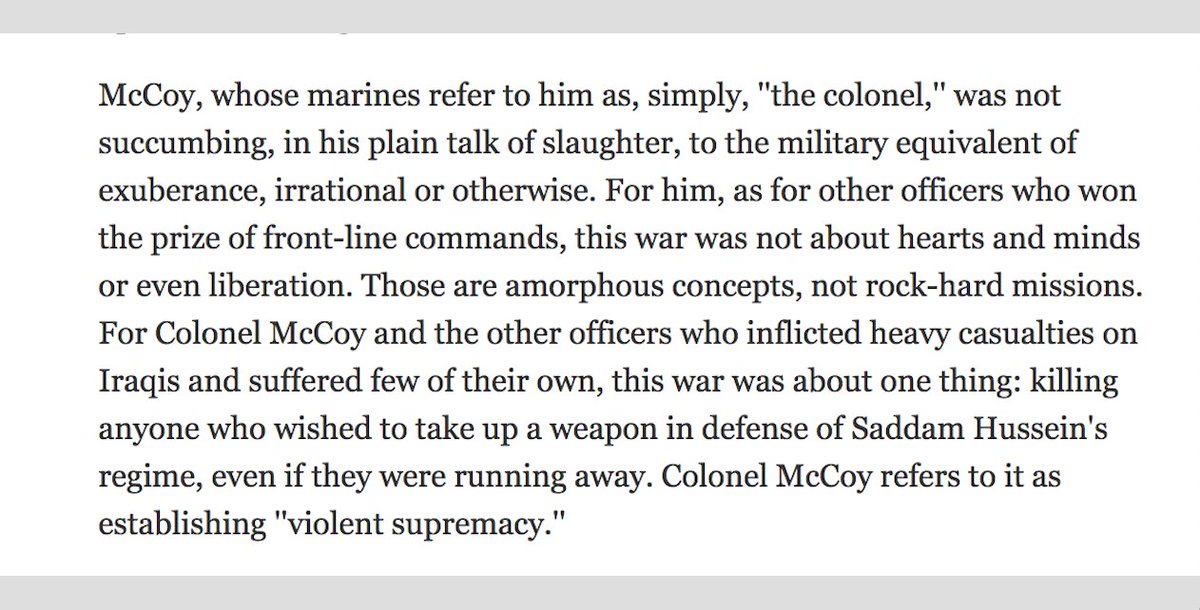

66) We had to talk w/ the battalion commander, get his permission. It was far-fetched. Why would he allow a dozen journalists to come along, ones who drove their own vehicles, which could be a security nightmare for his unit? He was Lt. Col. Bryan McCoy (photo in previous tweet).

66) He also spent a few minutes on one of our satphone-connected laptops to read the latest news about Pvt. Jessica Lynch getting captured in nearby Nasiriya. He finished, and I asked how he would prevent that from happening to the Marines in his unit.

67) "There are two kinds of people on this battlefield," he said. "Predators & prey. Don't be prey. Don't be an easy target. We'll do the ambushing. We'll do the killing. The best medicine is aggression & violent supremacy. After contact they will fear us more than they hate us."

70) McCoy added, "Make peace with your maker, and ask forgiveness for what you are about to do to the Iraqi army."

72) War can kill you, horrify you, scare you in infinite ways. Bullets, bombs, disease, torture, landmines, thirst, knives, hunger (a partial list). Events that are unremarkable in peacetime turn frightening, like the onset of night, darkness. Even the weather becomes terrifying.

78) After midnight, the storm blew itself out and the convoy started up again, in darkness, no lights.

79) War is more than bang-bang combat. It is refugees, corpses, abandoned houses, collapsed bridges, cratered roads, lost dogs, raw sewage, a stillness that is not natural. 3/4 was a frontline battalion, so we began seeing and smelling these things.

82) In the photo above, notice the woman on the right. In her right hand, there's a white fabric. She was waving it as they walked, and other women and children did the same, waving anything that was white, so they wouldn't get shot. It didn't always make a difference.

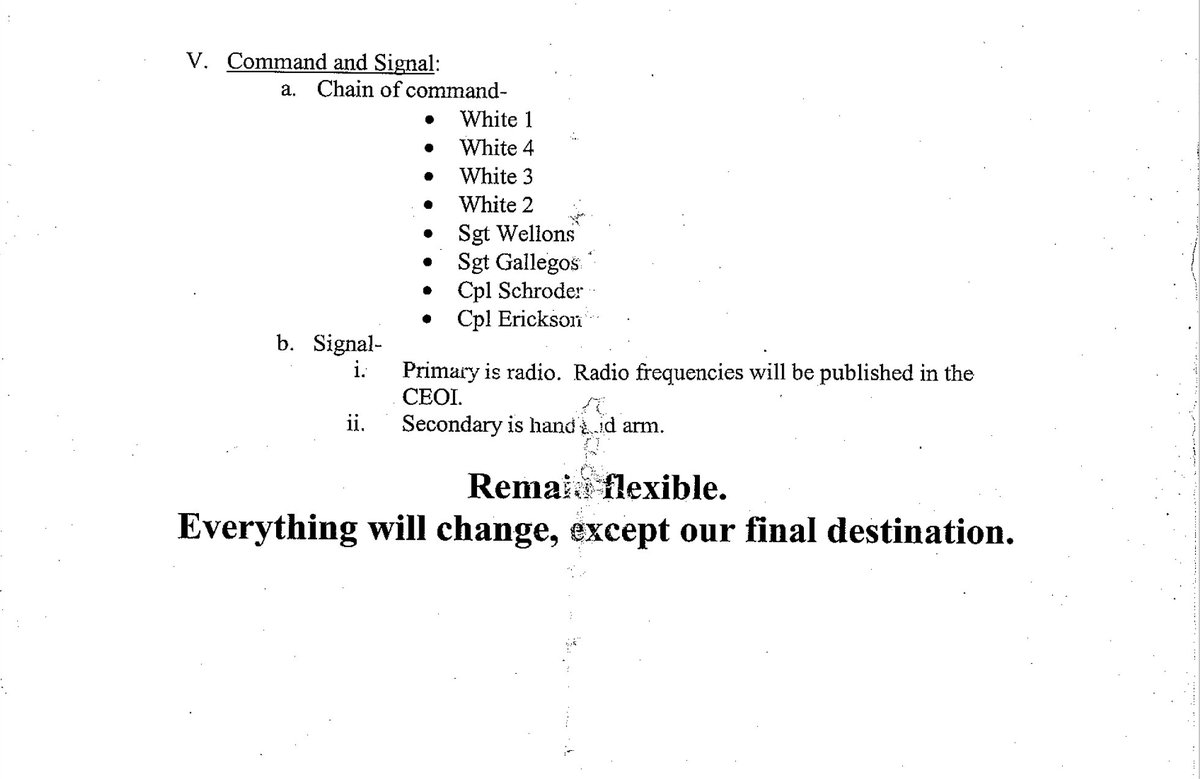

88) The cliche is true, that no battle plan survives 1st contact with the enemy. War demands improvisation; you can't control the chaos. The battles 3/4 would fight, the resistance it would meet, how it would react -- these things were largely figured out on the fly.

89) This revealed itself in ways that included the absurd. One day, I drove with the battalion's intel officer, Capt. Bryan Mangan, to the regimental HQ, five miles from 3/4's camp. Mangan brought me into an intel briefing but a higher officer quickly threw me out.

90) Afterwards, Mangan was supposed to lead a regimental psy-ops team back to 3/4's camp. As we got ready to leave the regimental HQ, Mangan saw the psy-ops Humvees drive out ahead of his Humvee.

91)

"Where are those idiots going?" Mangan asked his driver.

"They're following you," the driver said.

"But I'm here," Mangan noted.

"They think they're following you," the driver said.

"Why?"

"Because you're in a Humvee," the driver said, "and that's a Humvee they're following."

"Where are those idiots going?" Mangan asked his driver.

"They're following you," the driver said.

"But I'm here," Mangan noted.

"They think they're following you," the driver said.

"Why?"

"Because you're in a Humvee," the driver said, "and that's a Humvee they're following."

92)

Mangan was furious.

"Do they have a radio?" he asked.

"Yes," his driver replied.

"Can we call them on it and tell them to get their asses back here?"

"Let me check," his driver replied.

The driver ran to the communications tent. He returned in a minute.

"No, sir," he said.

Mangan was furious.

"Do they have a radio?" he asked.

"Yes," his driver replied.

"Can we call them on it and tell them to get their asses back here?"

"Let me check," his driver replied.

The driver ran to the communications tent. He returned in a minute.

"No, sir," he said.

93)

As Mangan tried to figure out what to do, I chatted with his driver.

"Why do you think you're here?" I asked.

"We're here to liberate these fucking eye-rackis," he replied.

As Mangan tried to figure out what to do, I chatted with his driver.

"Why do you think you're here?" I asked.

"We're here to liberate these fucking eye-rackis," he replied.

94) This episode, a bit amusing, hints at a serious truth -- the deadly chaos of an army at war. If two Humvees couldn't proceed in an orderly fashion behind the frontline, imagine what happens in the explosive mix of adrenaline and fear and exhaustion of battle. That's coming.

97) 3/4 was an attack machine. I want to take a moment to explain its firepower, because you can't understand the killing it was capable of inflicting in the coming days without knowing the weaponry it possessed. It would be hard to imagine a ground unit with more muscle.

99) The core is three infantry companies and a weapons company, most of them in armored personnel carriers, also in Humvees and trucks, equipped with assault rifles, grenade launchers, mortars, etc. Also a sniper team. Led by a commander, McCoy, whose call sign is Dark Side Six.

101) 3/4 was going into battle the next day, and Col. McCoy would not be shy about using force. He would establish, as he put it, "violent dominance." He told me and a few other journalists the following as the fighting got heavier, moving from the desert to towns and cities:

102) "If they're dug into a building, then I drop the building on them. My idea of a fair fight is clubbing baby harp seals. We're not in an open desert anymore. We're dealing with civilians and irregulars. It's blue collar warfare."

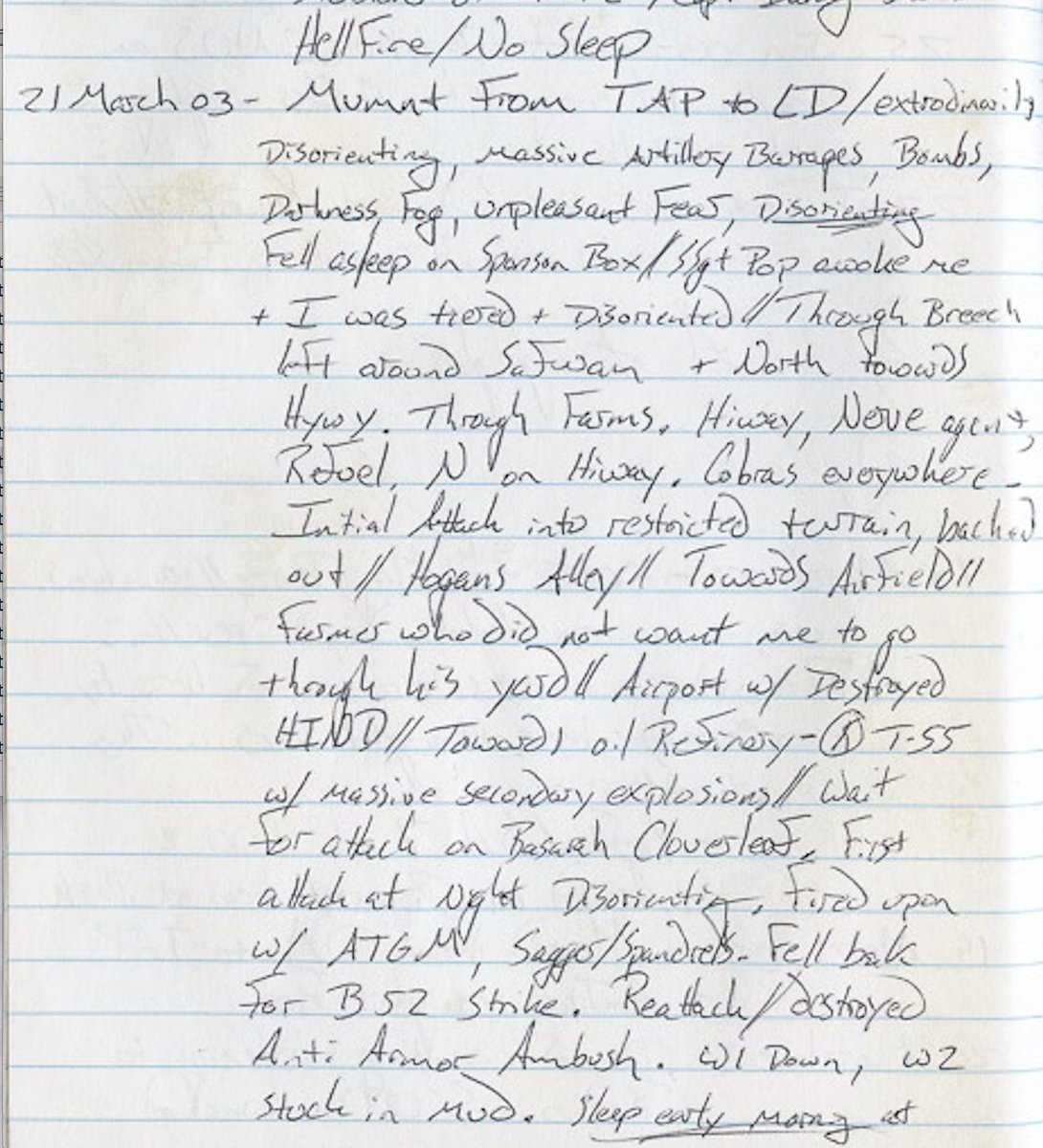

105) The battalion's tanks, including McLaughlin's, went first; almost always they led 3/4's attacks and movements. In his diary, McLaughlin recorded the series of rapid firefights his Abrams had that day.

106) "Fire w/Coax at oncoming traffic to keep rt clear ... Car pops out on me, 200 meters. Sgt. Wellons coaxed it, vehicle slowed down, swerved left off road + hit tree. Civilian shot 5 times in back and legs. Continued progress to Afak."

107) "Pushed mostly through town until bridge at canal. Grove left front ... B6 opens fire on child in grove. We look + spot one man w/ red/white checkered headdress on w/RPG. Open up w .50 cal + 240. Massive fire into grove. People everywhere watching."

112) In war, whether you're a civilian or combatant, there's an infinite number of ways to die, an infinite number of possible tragedies. On March 29, 2003, one of the 3/4 Marines lost his life after his Humvee slipped into a canal and flipped over, trapping him.

113) He was Lance Corporal William White, 24, from Brooklyn, NY. It happened at night, when nobody could see what had happened. The other Marine in the Humvee, Lance Corporal Derrick Jensen, got out and tried to save his comrade. I talked to Jensen about it afterwards.

114) "We were underwater," Jensen told me. "You've got to stop and think, but you don't really have time to stop and think. You've got to be quick about it and decide, What do I need to do here, where do I need to go?"

115) "All at once, I was talking to God at the same time and screaming for White when he was still underwater. I was praying out loud, just hoping to God that I could get out of there. I was screaming his name, 'White, oh White, please no.'"

116) Jensen got White out but he wasn't breathing. After mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, White breathed again. It was night, darkness all around, no Marines to be seen. White was barely conscious, freezing from the cold water and night air. Their radio was in the submerged Humvee.

117) Jensen had to leave White to find help but he was disoriented, in enemy territory. "I had no idea where I was going," Jensen recalled. "I ran over a couple of hills and had some dogs chasing after me. I was just shouting 'Help, somebody help me.'"

118) He finally came upon other Marines, and they headed back to get White. But where was White? Somewhere along the canal, but it was night, so Jensen didn't know the exact location. They had to listen for White's labored breathing.

119) "The whole time when I was swimming with him, he would make a wheezing noise," Jensen said. "It was just a God-awful noise, wheezing just as loud as he could do it. I would stop the Marines every now and then and say 'Shhh, listen.' I could hear the noise as we got closer."

122) Col. McCoy, the battalion commander, often talked with us about his tactics. He would come to our vehicles, and if we were making coffee, he'd have a cup and chat. On March 30, 2003, camped outside Diwaniya, McCoy talked to us about the "Afak drill," as he called it.

123) "What we try to do is go in there and dominate the place by showing violent dominance and letting them know that we can do whatever it takes, escalate to any level," McCoy said. This wasn't an unusual remark. On another day, here's what he said about the invasion overall.

124) "We're here until Saddam and his henchmen are dead. It's over for us when the last guy who wants to fight for Saddam has flies crawling across his eyeballs...Sherman said that war is cruelty. There's no sense in trying to refine it. The crueler it is, the sooner it's over.''

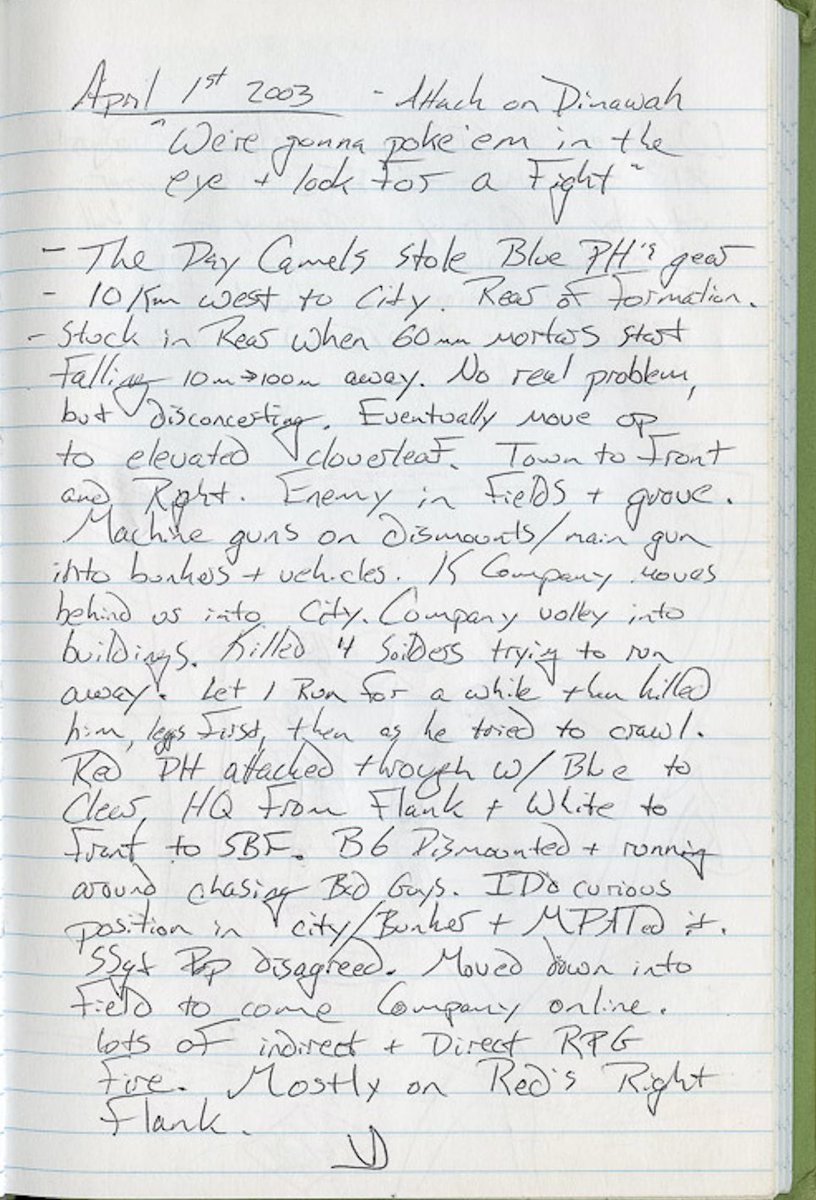

127) Sorry, the attack I mentioned in prior tweet was on April 1 not March 31. On this day 15 years ago, 3/4 took a break outside Diwaniya. I don't want to get ahead of things but events flew by from April 1, and at the end of it all, McLaughlin wrote a "Kills" list in his diary.

130) I read that now and his reference to "our final destination" gives me chills.

132) Fifteen years ago today, the attack on Diwaniya. McCoy had no intention to occupy the town – his destination was Baghdad. He just wanted to punch the Iraqi military forces there, so they’d stay put and not ambush the invading U.S. forces driving by on the nearby highway.

133) The unilateral journalists had to stay back; only the embedded journalists were allowed to join this attack. Simon Robinson of Time was with McCoy. “We’re going to throw some bait into the water and see if the sharks come out,” McCoy told him.

134) When 3/4's tanks and APCs moved into Diwaniya, Iraqis fired back with mortars, RPGs and small weapons. Robinson listened to the radio chatter. “Yeah baby,” one Marine said. Another boasted, apparently after machine-gunning an Iraqi, “He just ate coax for breakfast.”

139) A civilian or a soldier dies in a war. Who gets to tell the story -- who has the right to tell it? I've spent much of my life telling stories of death. The ones from Iraq were among the most complicated. I don't mean the dodging-bullets part of it.

140) Imagine that your son or daughter or husband or wife is killed in a war. Someone tells you and the pain is instant. It hits you with the first words or maybe before that, when you see the expression of the person who has come to tell you and you realize what has happened.

141) The first news is usually minimal. How, why, where -- details tend to emerge slowly and chaotically from warzones. Some family members want to know everything, others don't, it's too painful. Do they want the public to know the details? Some do, some don't.

142) Journalists in warzones see people die, hear their final words, know how they died, whether they suffered. We know more than a grieving family might know, more than the grieving family might want to know -- more than it might want the world to know.

143) When my story was published about Lance Corp. William White dying after his Humvee slipped into a canal, his family was shocked. They contacted my editors to say they hadn't known the details we published -- the military had told them little. We should have notified them.

144) What if a family doesn't want some details published, because they are too graphic, too painful? The death of a loved one at war -- how much of the story belongs to the family, how much should a writer hold back in deference to their wishes?

145) As a writer of war stories, I want people to listen and learn from what I've seen and experienced. I want to write stories that are as powerful as they can be. But this can conflict with what a grieving family might wish to be written.

147) There would be strong and reasonable objections to what I would write about his last moments. That's tomorrow.

150) We got into our vehicles and drove toward the city. On the road, a woman surrounded by her family waved a white flag (burlap bag, actually). Marines hovered over prisoners they'd taken. Iraqi military vehicles that had just been hit were smoldering.

154) There were prisoners. One, lying on the ground, pleaded for his life with Simon Robinson, a Time reporter. "Don't kill me," the Iraqi asked in English. "Please, I can't fight. My arm, don't twist it left or right. It's broken."

155) Imagine you're a civilian trapped in a battle like this. Troops are shooting all around you, artillery shells are exploding. Stay or run? I've been in these situations -- you never know what to do. Fleeing is not just an impulse, it could save your life (or take it).

156) U.S. troops assumed that cars & trucks in battle zones were hostile. As combat wound down in al Kut, a dump truck drove toward McLaughlin's tank. He fired his rifle, another tank fired its .50 cal. The bullet-riddled truck stopped. 20 women, kids and men got out, screaming.

158) A Marine was killed at al Kut. His name was Mark Evnin, a corporal from Vermont. He was firing a grenade launcher at Iraqi fighters when he was struck by two bullets. Evnin was put into a Humvee and rushed to the first-aid station where I was standing.

159) A doctor and medics, M-16s slung over their backs, worked on him. "Left lower abdomen...He's in urgent surgical...Wriggle your toes...Iodine...He needs medevac now...Keep talking to us." Evnin was stretchered to the medevac helicopter as soon as it landed. He died aboard it.

160) Hours later, as night fell in Burlington, the military notified Evnin's mother, Mindy. John Koopman, who was embedded with 3/4 and knew Mark, visited Mindy in Vermont after the invasion and wrote about the moment of notification.

161) Mindy Evnin was getting ready for bed when she heard the knock. She feared what it might be. She opened her front door, saw three men in military uniforms and said to them, "Just tell me if he's been wounded, dead or missing."

163) War is chaos & war reporting is chaos. Not just the task of observing wild events, but how people recall them (you see just a sliver yourself). For some people, time slows down in a crisis, for others it speeds up. Little is synchronized -- time, perception, memories.

164) Part of the chaos of war reporting is the sensitivity of what you're investigating. You ask people what happened -- the killing they committed or witnessed, the torture they endured, the rape they survived. How do you ask these questions?

165) I was lucky in the invasion because more than a dozen journalists followed 3/4 (an anomaly -- I don't think any other battalion had as many). We shared what we knew. I still don't understand everything but part of what I understand is because of them, what they saw & heard.

166) The final bit of chaos is how much of what you know do you publish? You have seen and heard a lot -- words, corpses, grief, fear. Your choices are made in sub-optimal conditions; my workplace was my SUV, my physical state was near exhaustion.

167) When Mark Evnin died, I chose to use words, including some of his, that I thought would convey, most powerfully, what happens in war. After my story came out, his mother contacted my editors to object & wrote a letter published by the magazine. Here's some of what she wrote:

169) I can't disagree with her. I might have been wrong to write as much as I did. I don't know. I wanted to fully describe the excruciating scene I had witnessed. Reporting on the chaos of war, sometimes you get it right, sometimes you don't, and sometimes you don't know.

174) The toppling in Firdos Square -- a seemingly triumphant yet deceptive moment -- was caused and shaped by the media in crucial ways, sometimes intentionally, sometimes not. The process was started, unintentionally, many days before the statue came down.

175) The journalists with McCoy's battalion had satellite phones, mostly Thurayas. We used them to file our stories and photos, and talk to our editors, family and colleagues elsewhere in Iraq (to learn what was happening in the rest of the country).

177) Journalists at the Palestine faced a lot of pressure. They were under the constant threat of U.S. bombing as well as arrest or worse at the hands of the Mukhabarat. They weren't supposed to have satphones -- Remy hid his behind a ceiling panel & spoke to Laurent in whispers.

178) Laurent had a box of Cuban cigars and lit up from time to time with Col. McCoy, occasionally mentioning what he was hearing from Remy at the Palestine. Gary Knight, another photographer in our group, also mentioned to McCoy that journalists at the Palestine were in jeopardy.

179) In the desert, McCoy had a million other things to think about. But later on, as his battalion entered Baghdad, he received orders to secure the Palestine, which he eagerly did. The statue of Saddam Hussein that his battalion toppled -- it was outside the Palestine.

183) The final four days of the invasion were monumental, politically and personally. Because of that, and because this thread is nearing Twitter's limit of 200 tweets, I'm continuing my narrative on a new thread. Just click the tweet below to keep going.

Loading suggestions...