Let’s look at another famous ‘mystery animal’ image. This time the 'de Loys ape' photo of 1920(ish), taken in the Catatumbo River basin of #Venezuela. You surely know the photo already. But do you know its complicated backstory? Join me as we explore it in this loooong thread…

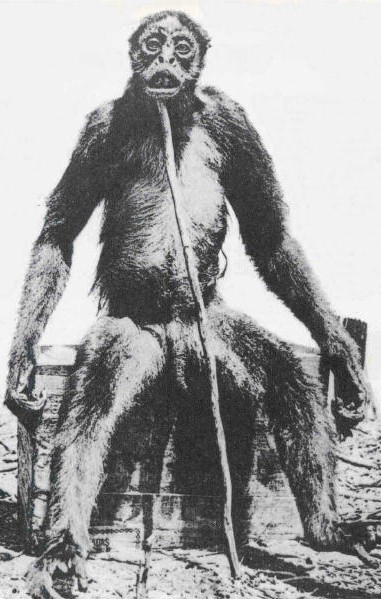

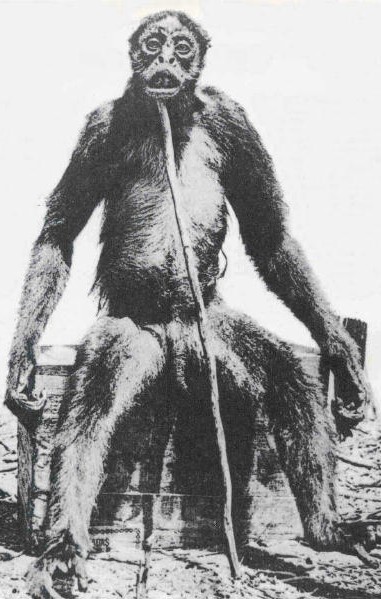

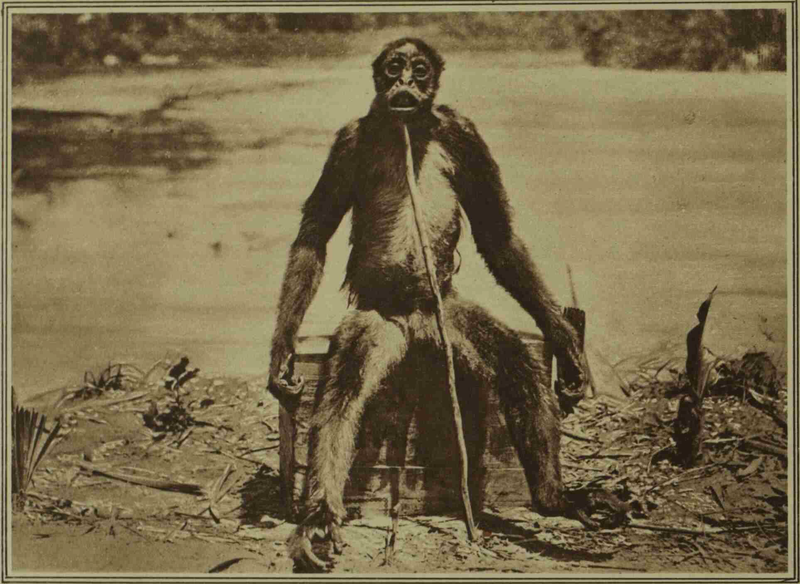

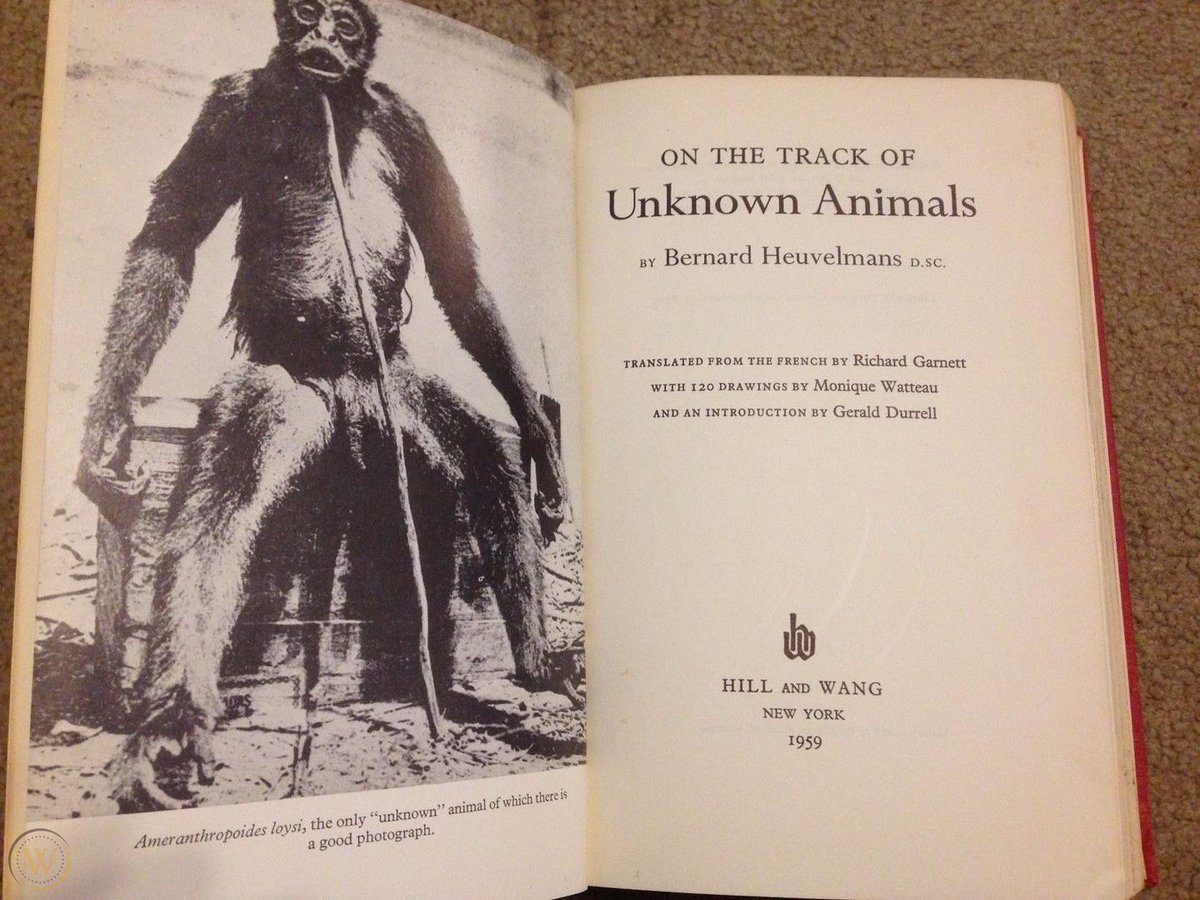

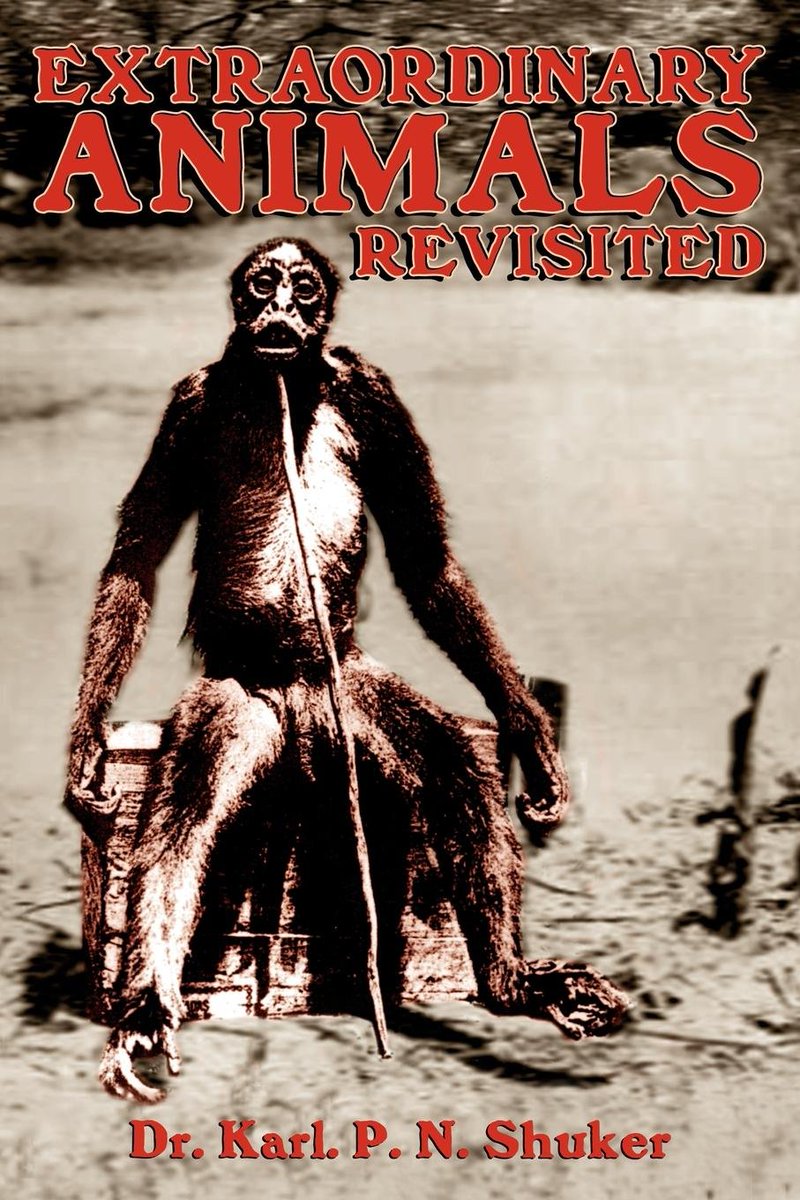

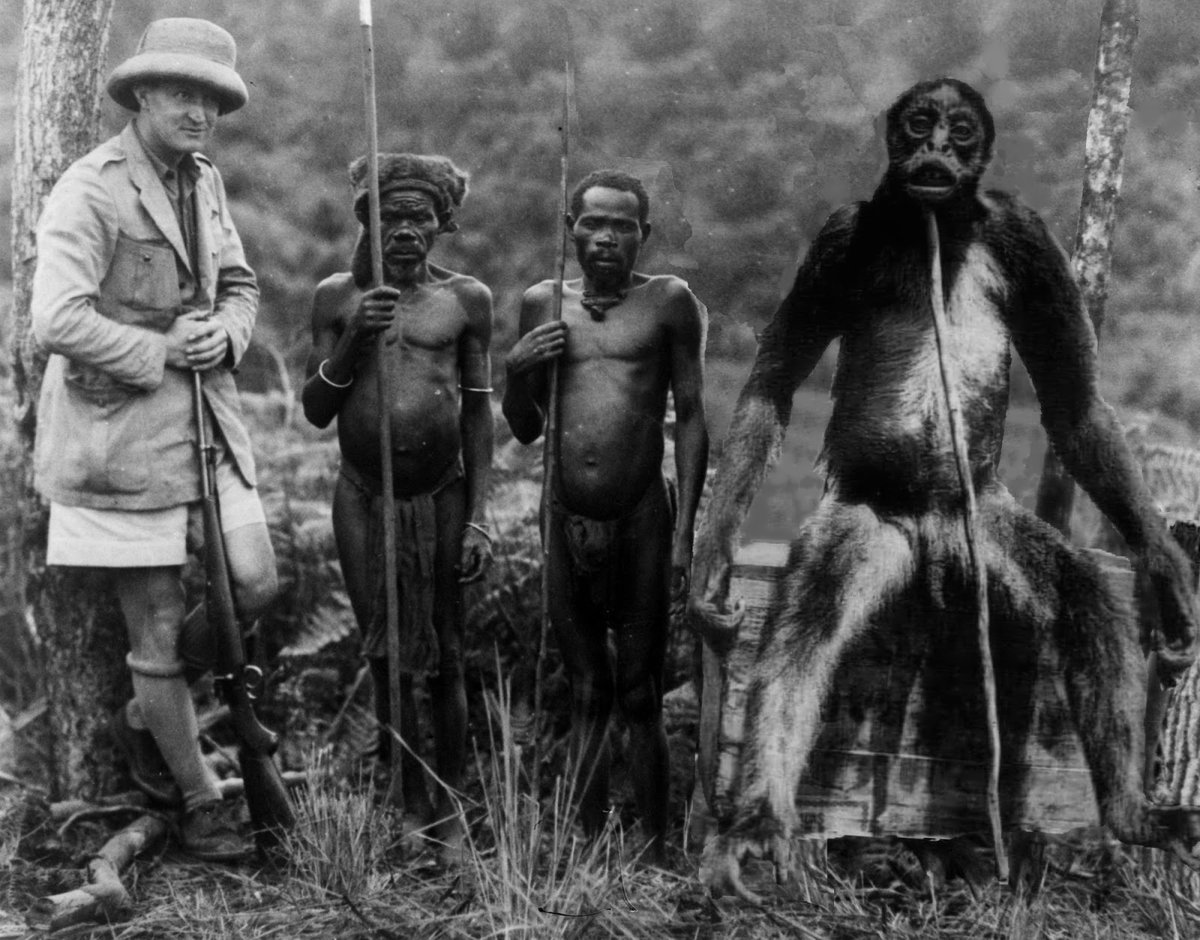

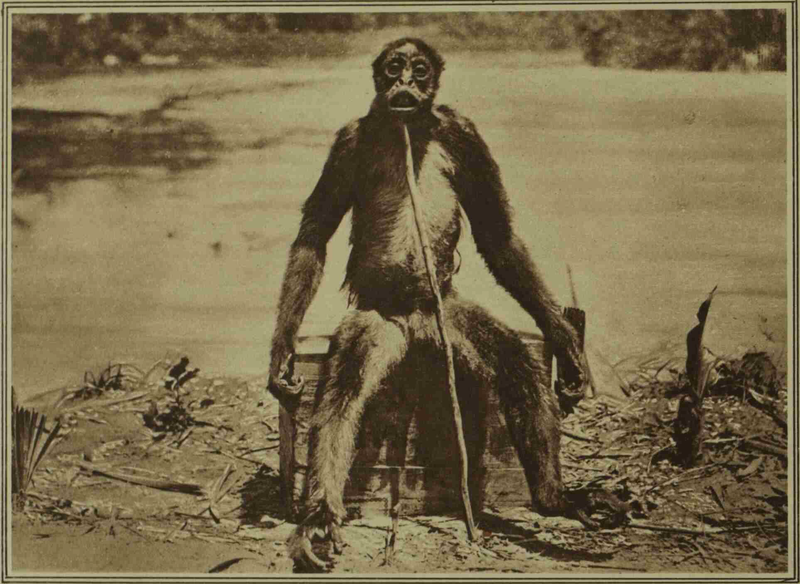

The photo shows a large, hairy primate, sat on a wooden box, a stick propping it up beneath the chin. The version shared most often is cropped, so you only see what looks like bare ground or the river behind the animal. #cryptozoology

The uncropped version shows the opposite river bank and some hacked-down plants surrounding the animal.... #primates #monkeys #mysteries

This photo always scared the hell out of me as a kid, so much so that I’d avoid looking at it in certain books. I know I’m not alone here: it seems to be widely regarded as quite scary...

The story is that de Loys and his party encountered a mated pair of these animals (initially mistaken for bears) which behaved aggressively, breaking branches and flinging faeces. The team went to shoot the male but he dodged and they killed his mate. The male ran away.

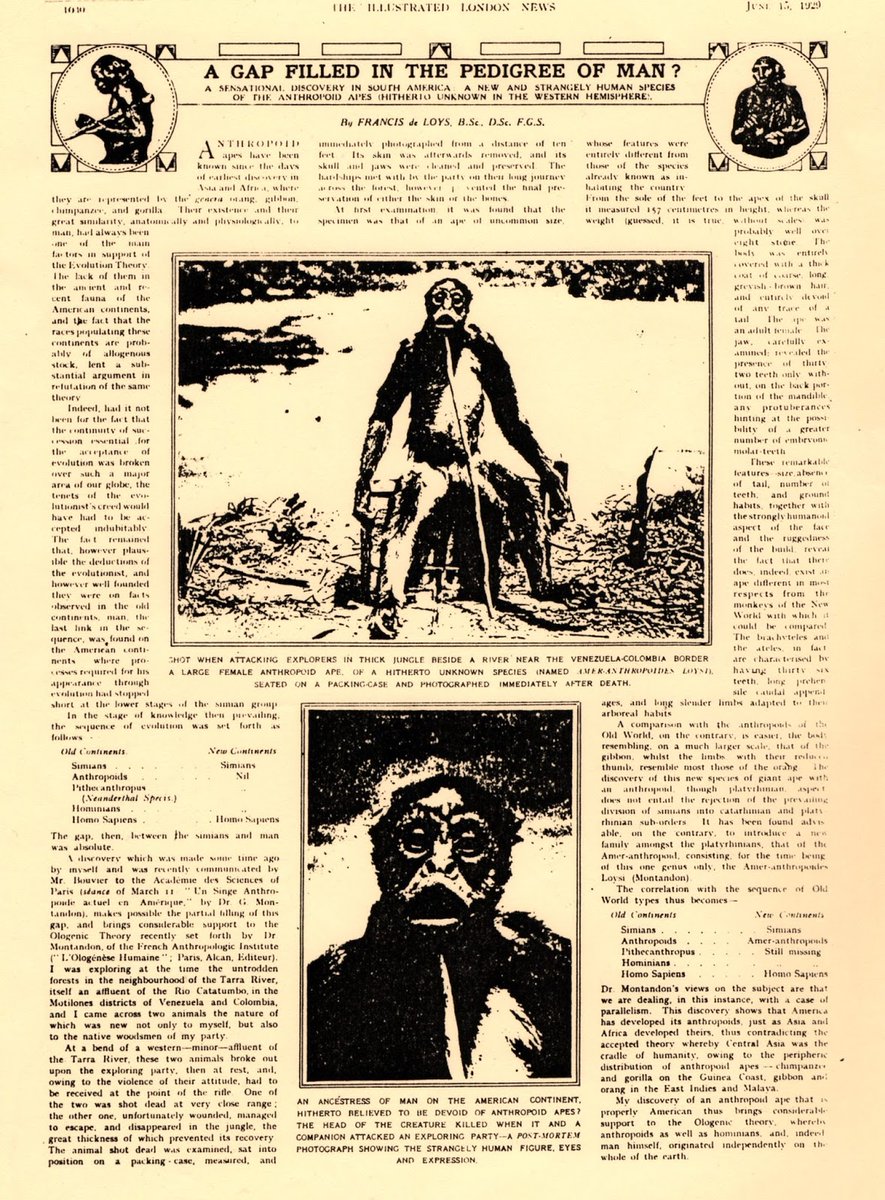

The ‘ape’ was large (1.5 m tall – or was she? Hold that thought – and over 50kg), had no tail, and had a human-like tooth count of 32 (rather than the 36 typical of American monkeys)...

.... de Loys and his colleagues supposedly recognised this animal as something new, sat it up on a wooden crate (used for transporting petrol) and took a photo. They seemingly never thought to take one with a person for scale (though read on).

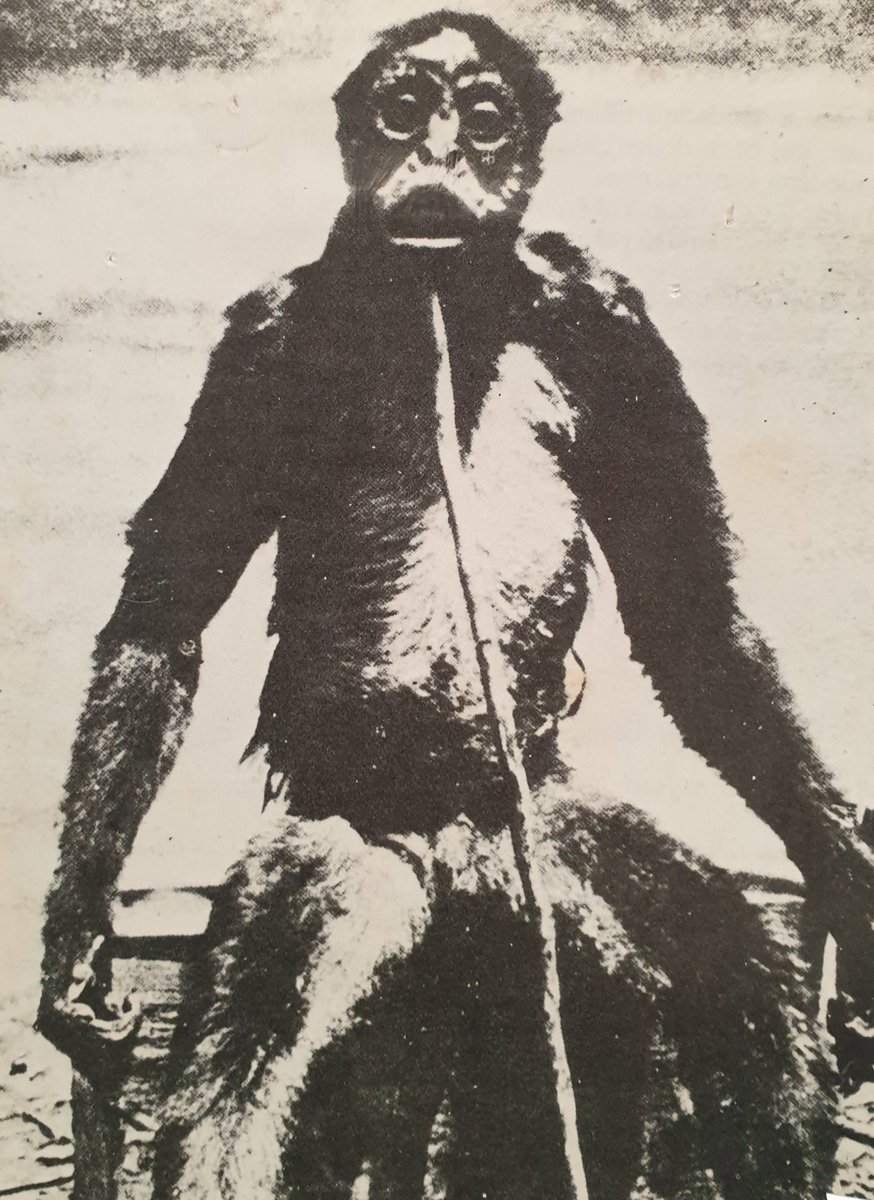

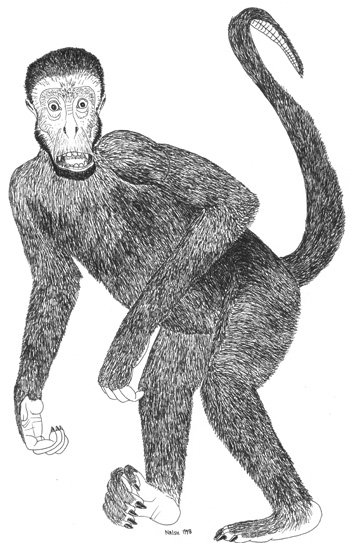

A few anatomical features are worth mentioning. Pale circles ring the eyes, the forehead is pale, and the nostrils are directed sideways and forwards as per the ‘platyrrhine’ condition of American monkeys.

We see that the ‘ape’ has long, hook-shaped hands lacking a large or obvious thumb. The feet are also hook-shaped and with a long distance between the hallux and the other toes.

On returning home, de Loys published a brief article in 1921, but not until March 1929 did it receive longer attention…

... They were ill-fated, were in aggressive conflict with local Indians, and only four of the original 20 expedition members survived.

They lost various of their belongings (perhaps including additional photos of the creature) and weren’t able to retain the animal’s carcass. They did try to keep its skin and skull. Buuut…

The skin was apparently lost in a boating accident. Supposedly, the skull was retained and then used as a salt container… which caused it to deteriorate and eventually fall to pieces. By the time they arrived back home, they had no physical remains of the animal.

A point on nomenclature: the name for the animal should be written ‘de Loys’ ape’ or ‘de Loys’s ape’ (as in, the ape belonging to de Loys). But most authors have NOT followed that convention, instead writing ‘de Loys ape’. I’m going to follow the last of those options. Ok…

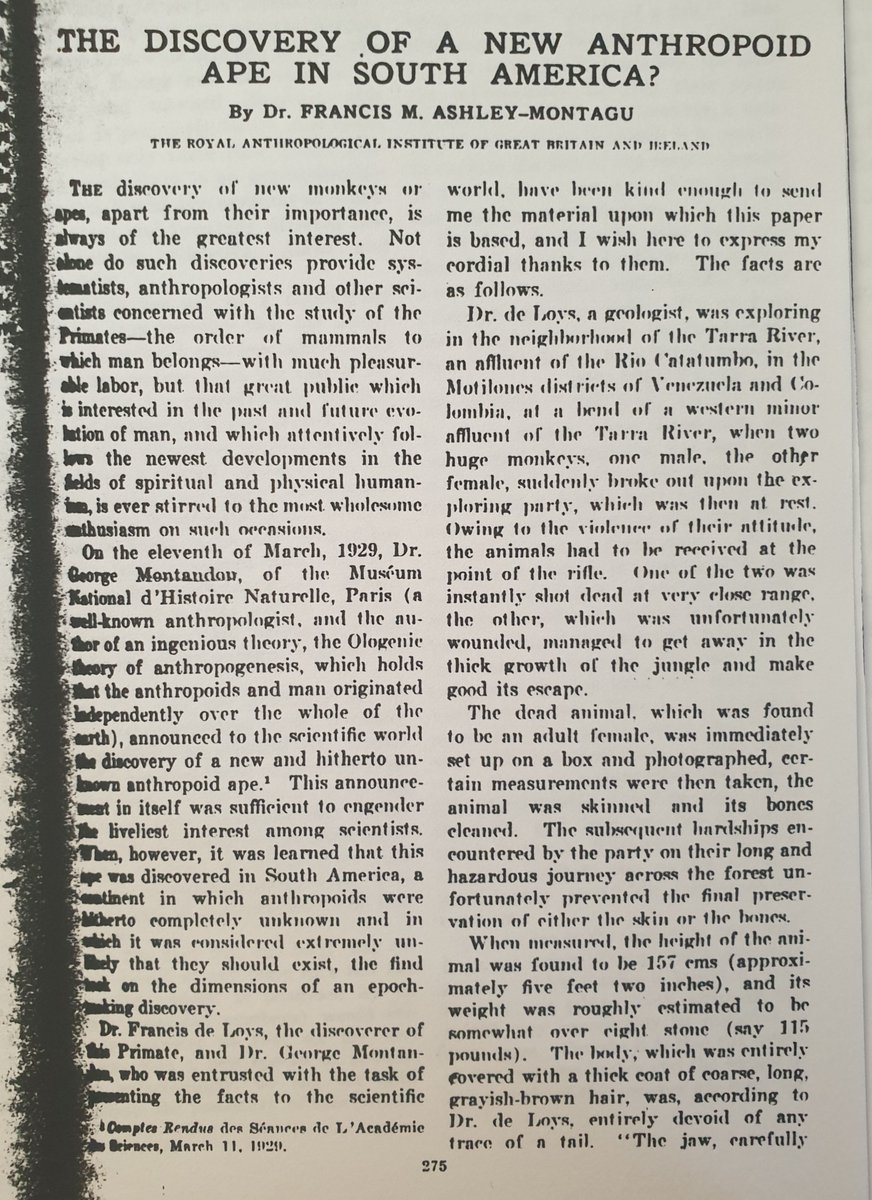

In March 1929, Montandon published a paper on de Loys ape in the respected journal Comptes Rendu, wherein he described it as a new species. Montandon said that the giant clitoris _could_ mean that it was a new species of spider monkey (Ateles), but...

Actually, Montandon named it ‘Amer-anthropoides’ but hyphens are today disallowed from generic names, so we now ignore the way he wrote it. It was deemed distinct enough for a new family too, the Ameranthropoidae (technically, it was probably supposed to be Ameranthropoididae)...

Montandon immediately deemed it relevant to the evolutionary model he favoured for humanity, termed hologenesis. We’ll come back to this.

Montandon did a LOT of popularisation of his proposal, in fact publishing SIX articles on de Loys ape in 1929 alone, ranging from technical papers to popular magazine pieces.

This was a phenomenal claim, and it got a lot of attention. The story was initially circulated in France and had a mostly positive reception there, in part because Édouard Bourdelle, chair of zoology at the national museum, published a positive take on the creature…

Bourdelle likened the creature to another one, said to have been captured in the Belgian Congo and taken to the USA, said to be 1.5 m tall and 54 kg. These figures are about exactly the same as those later given for de Loys ape by Montandon...

.... and it’s likely that this is where Montandon got them from. Indeed, Montandon commented on this Congolese case in one of his 1929 articles, saying that this African animal was likely a hybrid between a monkey (a guenon) and a human, and...

... he also – on this occasion – endorsed this view for de Loys ape too, saying that it could be a hybrid between an indigenous woman and a spider monkey. His views on the creature were clearly vague and prone to change, and also shot through with racism.

Keith further noted inconsistency about the animal’s size. Both de Loys and Montandon had initially said that it was 4ft 5in (134.6cm), but later changed this to 157cm, a notable discrepancy. And in a 1930 article, Montandon gave the height as 123cm.

A curious aside on the case comes from Hans Weinert’s argument of 1930 that de Loys ape should not have been named Ameranthropoides (since this name – especially when written ‘Amer-anthropoides’ – supposedly evoked comparison with Anthropoides, a genus of crane), but...

... Megalateles instead. This new name basically means ‘giant spider monkey’.

Montandon was aware of this and agreed with it, and in 1943 argued that Megalateles should formally replace Ameranthropoides to avoid misinterpretation.

The fact that Montandon was happy to accept and promote this attempt at re-naming might show that he wasn’t all that committed to the idea of de Loys ape being anything other than a spider monkey when challenged.

Surely, if you were convinced that you had something new (a South American hominid or pre-hominid), you’d stick to your guns, right?

Remember the box the ‘ape’ is sat on? Montandon argued that the box was 18in tall and published photos of spider monkeys and a man sat on the same sort of box in order to verify the creature’s height...

Montandon, of course, continued to support the distinct status of Ameranthropoides in 1930.

The result of these pronouncements is that the 1930s and 40s saw the case as one that could only be resolved via the discovery of another specimen. As documented by Bernardo Urbani and Ángel Viloria in their 2008 book (more on this later)...

.... some authors who explored the region said that de Loys ape could only be a spider monkey.

Rather than disappearing from the literature or being forgotten, it’s impressive how often de Loys ape was mentioned post-1929, including by a great many zoologists known for other things.

Some – like Mikhail Nestourkh in the Soviet Union – declared it a hoax and decried Montandon’s hologenesis as inadmissible. Others (like French explorer Roger de Courteville) thought it might indeed prove relevant to human ancestry, or that it could be a new monkey species...

Courteville regarded this as a sort of ‘missing link’, a living form of Pithecanthropus.

In his lengthy 1962 review of the world’s primates, Osman Hill reviewed the de Loys ape case and thought it most likely that the animal was a Brown spider monkey.

What’s notable is that primatologists had essentially given up on the hope of de Loys ape being real and a new species prior to the 1960s, and most discussions of it from the 1950s onwards frame it within the context of it being an ‘unsolved mystery’ or cryptid...

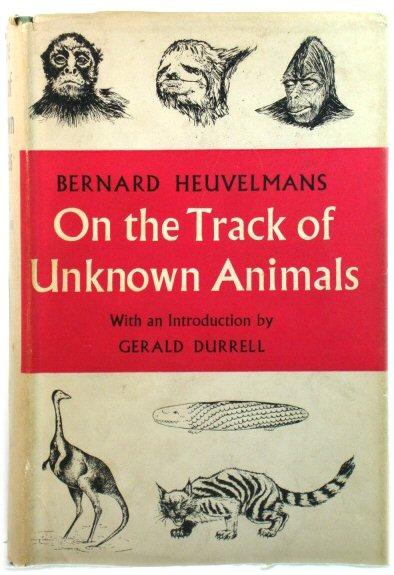

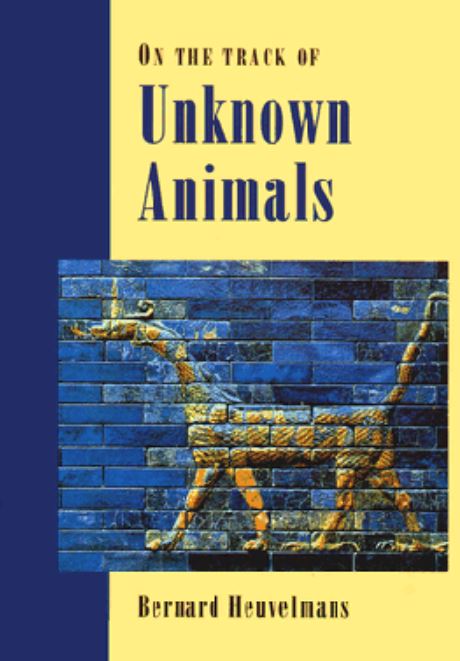

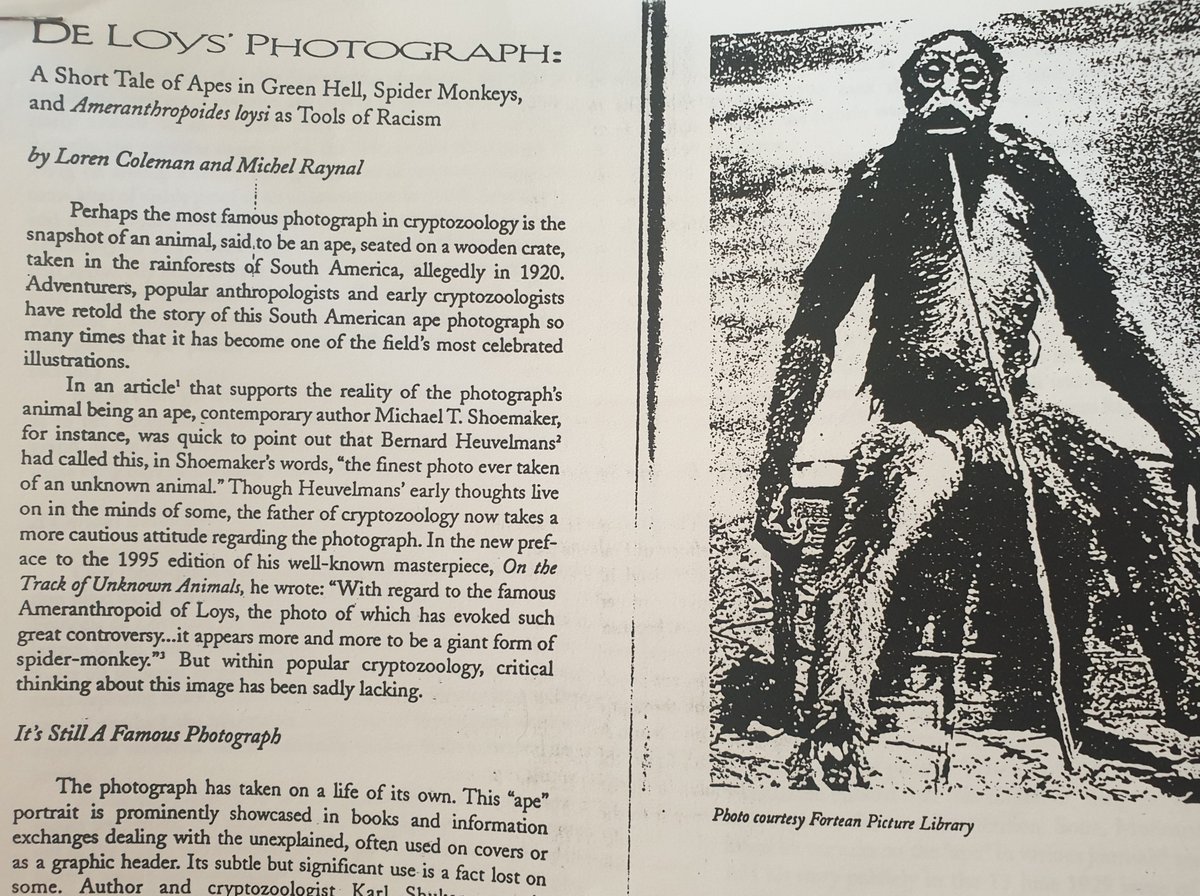

The most influential of these writings were those of so-called Father of #Cryptozoology Bernard Heuvelmans, who covered the case in his 1958 book On the Track of Unknown Animals and even featured the ameranthropoid as the frontispiece in the first edition.

Heuvelmans combined the de Loys account with stories and sightings of bipedal-walking South American ‘apes’ to seemingly endorse the reality of the creature (though it’s hard to really know what he thought, since his writing is very baroque and he rarely made clear conclusions).

He seemingly became less happy about the case over time, since it doesn’t feature in his 1986 list of mystery animals worldwide nor appear as frontispiece in the 1995 edition of On the Track. #cryptozoology

Sanderson argued that the unusual look of the animal in the photo could be due to bloating during decomposition, and also that the wooden box wasn’t 18 in high but 15.5 in, in which case the ameranthropoid was within the height of the larger spider monkey species.

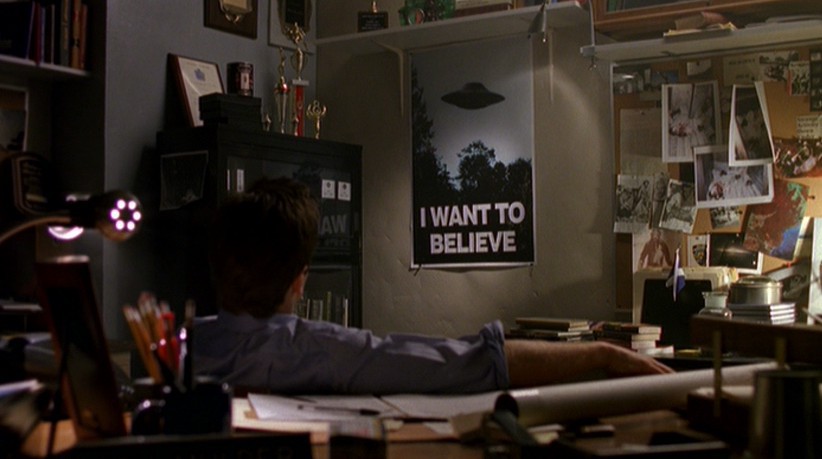

And this, in turn, probably helped establish it as a pop culture icon: a photo of de Loys ape is clearly visible on Fox Mulder’s noticeboard in The X Files… #XFiles

Like Heuvelmans, Shuker pointed to the fact that tropical South America is home to a list of ape-like creature accounts and pieces of art, some described as Bigfoot-like or Wildman-like, which (he said) “lends support to de Loys’s account”.

They don’t do any such thing though: ‘wildman’-type creatures are known from every place on the planet and are part of the mythology of every ethnic group, so the fact that they’re present in the Amazonian region, and depicted in art and sculpture, doesn’t mean anything special.

Furthermore, ‘wildman’ stories and sightings from the Amazon don’t clearly describe a platyrrhine with any anatomical similarity to de Loys ape, so, again, I don’t think they’re anything especially relevant.

Shuker is also one of several cryptozoologists who’ve pointed to the former existence of some especially big platyrrhines in the Pleistocene of Brazil (namely Protopithecus and Caipora) as being potentially relevant to the case of De Loys’ ape...

In a 2002 article, cryptozoologists D G Smith and Gary Mangiacopra also accepted the reality of de Loys ape and said that it deserved its own primate family: they appeared unaware of Montandon’s creation of Ameranthropoidae and proposed the new Mangiacopridae!

This doesn’t make any sense, since a family name should be based on the type genus for the family...

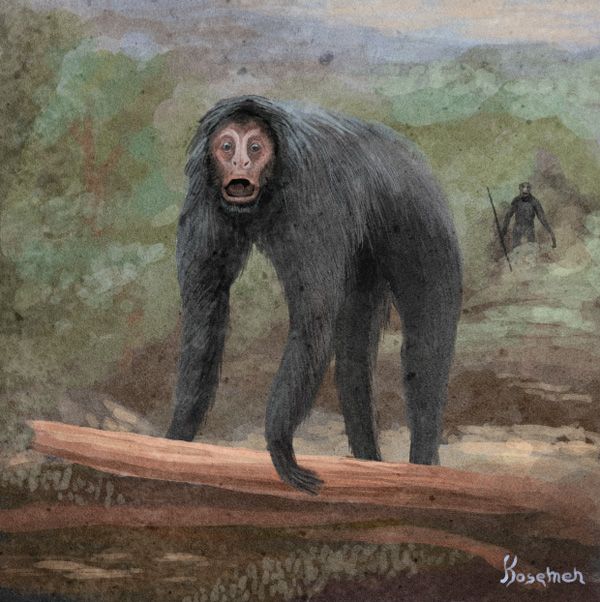

In our 2013 book The Cryptozoologicon, myself, @thejohnconway and @cmkosemen had fun with the idea of the ameranthropoid as a real primate. Namely, a terrestrialised, tailless descendant of Protopithecus, able to use tools. This was just an exercise in speculation though.

It is perhaps not widely recognised how big spider monkeys are, big specimens standing 152cm (that’s 5ft). They’re also very capable bipeds, regularly walk bipedally when on the ground, and are good at throwing objects (like branches) for several distances...

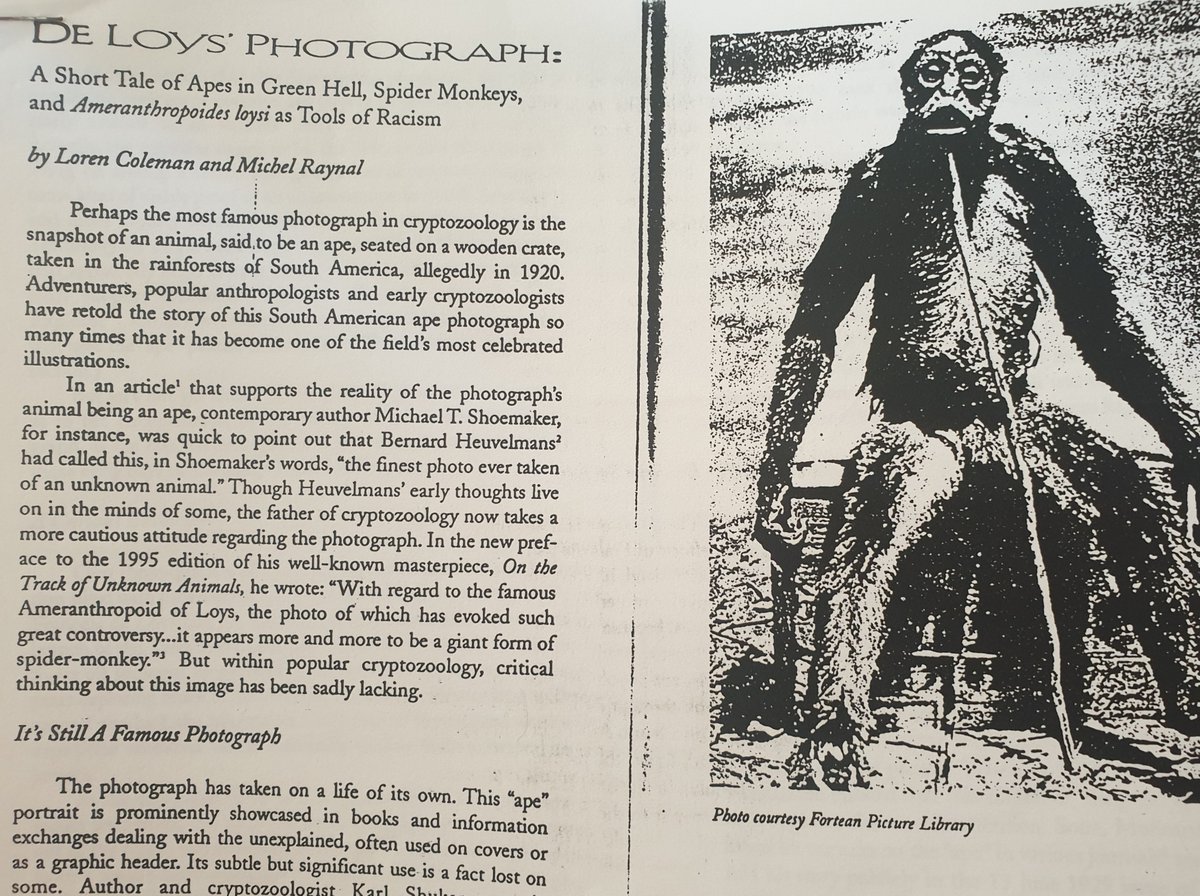

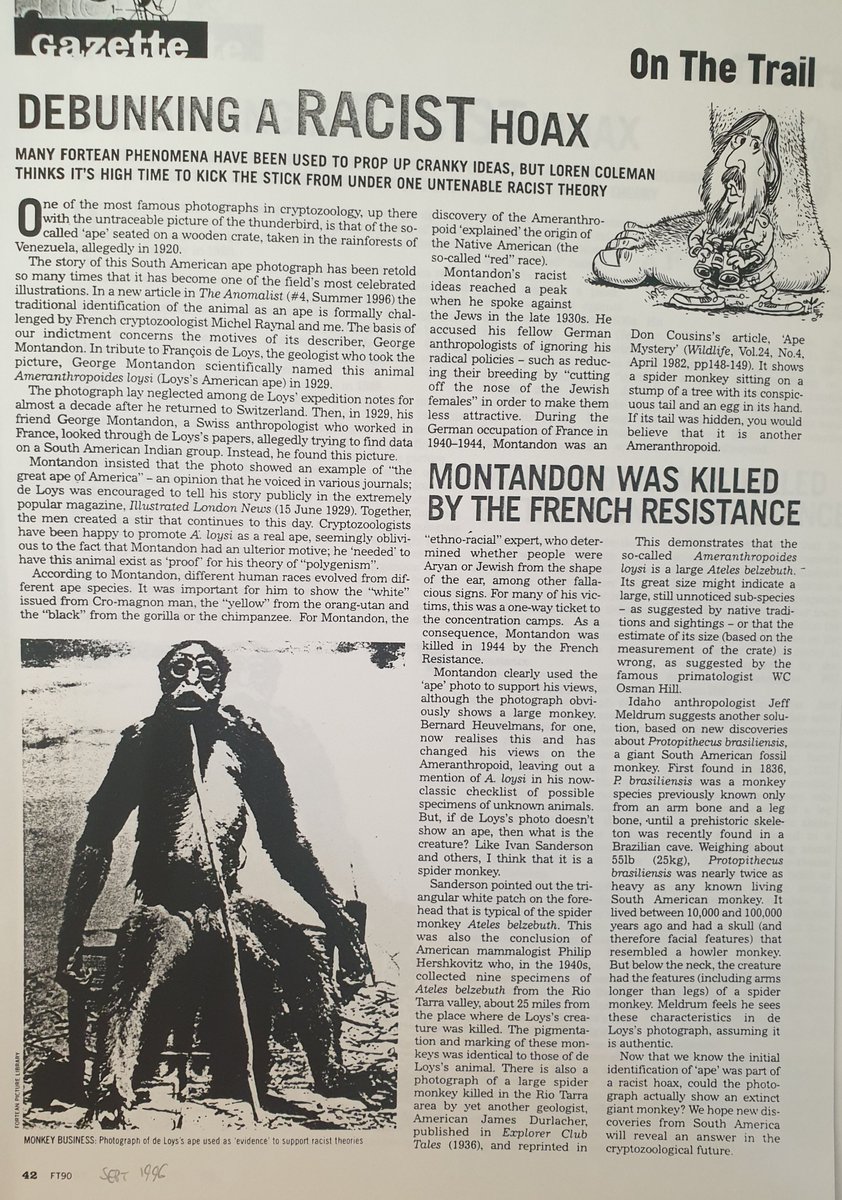

In 1996, @CryptoLoren also published an abbreviated version of the case in Fortean Times...

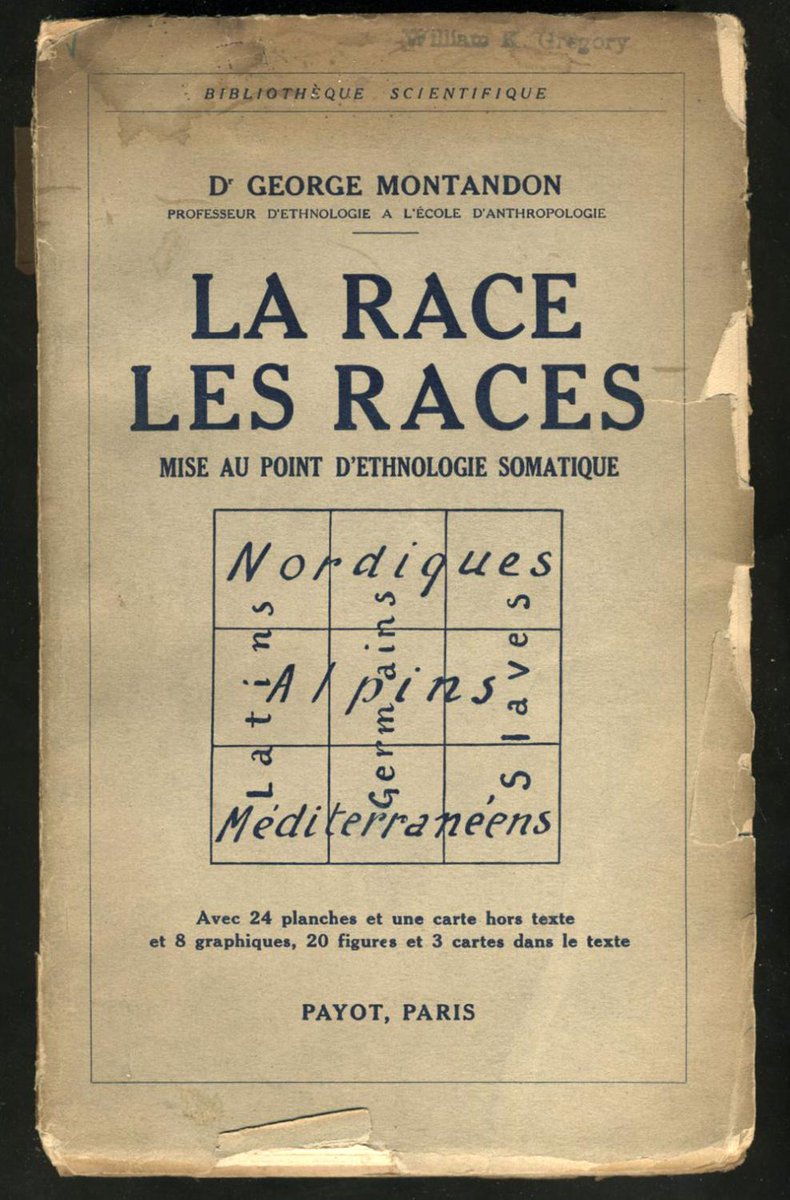

Montandon (the ameranthropoid’s namer, you’ll recall) was anti-Jewish and (prior to the discovery of de Loys ape) had already promoted a polyphyletic view of our species. This basically claimed that different peoples evolved, independently, from different non-human primates.

The one thing missing was a supposed ancestor for Amerindians, an ‘American human distribution gap’. De Loys ape – the ‘ameranthropoid’ – supposedly filled this gap and was thus used in a racist model.

Montandon was of course known for these strong racist views, and on August 3rd 1944 his house was attacked by the French Resistance. His wife was killed, and some sources say that he was too. However...

.... French author Louis-Ferdinand Celine stated that Montandon was only injured, transferred to Lariboisière Hospital, then to Karl-Weinrich-Kranhenhaus Hospital in Fulda, Germany, where he died on August 30th.

Was de Loys directly involved in Montandon’s racist, pseudoscientific use of the Venezuelan ‘ape’? Ultimately, we don’t know. In an article of November 1929, de Loys did refer to the racist idea that different groups of people had likenesses to different ape species...

.... and thus that humans were likely polyphyletic. But…

Urbani and Viloria also reveal that Venezuelan physician, academic and politician Enrique Tejera – a friend of de Loys – wrote a letter in 1962 in which he stated that the ‘ape’ was actually a pet spider monkey which de Loys had adopted and kept as a companion.

What appears to have happened is that things got out of hand once the discovery was embroiled within academic argument, and that de Loys – who became a respected petroleum geologist – was, by then, unable to back down and explain how it all started.

In the end, the view promoted by the people with the most substantial amount of experience with South American primates – that the ‘ape’ was no such thing but a known species of spider monkey...

This thread is the culmination of the checking of numerous sources, including articles by @CryptoLoren & Raynal, the books of Heuvelmans, Shuker, and Urbani & Viloria. Buy their books for fuller discussion and more detail! And thanks for reading. #cryptozoology #primates #mammals

Typo early on in thread: "In reality: no such renaming is allowed under the official naming names for animals..." should say "official code for naming animals"!

Loading suggestions...