Religion

Literature

Islamic Studies

Philosophy

religious studies

Literature analysis

Quranic interpretation

figurative speech

The ascription of irādah to the wall (literally “wanting to collapse”) is one of the most famous examples of figurative speech in the Qur’an, in which the wall is personified, and “wanting” means it is *about to* crumble to pieces.

Basically he says there’s no justification to posit majāz here (diverting from taking God’s statement as literally true), since there’s nothing impossible about a wall having irādah (volition) as long as we understand that He created that in it.

After all, says Shinqīṭī, all things glorify His praises (17:44) even though we don’t understand them, or perceive them as beings with the volition to do that! He also cites 2:74 and 33:72 to support his point.

However, he ends by noting that it’s common in Arabic poetry etc. to use “wanting” (irādah) for “about to” (muqārabah). This is what the majority call majāz! But Shinqīṭī begs to differ, especially when it comes to the Revelation.

We could ask him: what, then, is the point in the ayah mentioning the irādah of this wall? Should we understand that al-Khaḍir sensed that this wall had a hidden intention to fall?

No: the ayah tells us that al-Khaḍir set it upright, which means that it was already leaning over and on its last legs.* That’s what یُرِیدُ أَن یَنقَضَّ means.

*(Forgive me for mixing in another majāz 😇)

*(Forgive me for mixing in another majāz 😇)

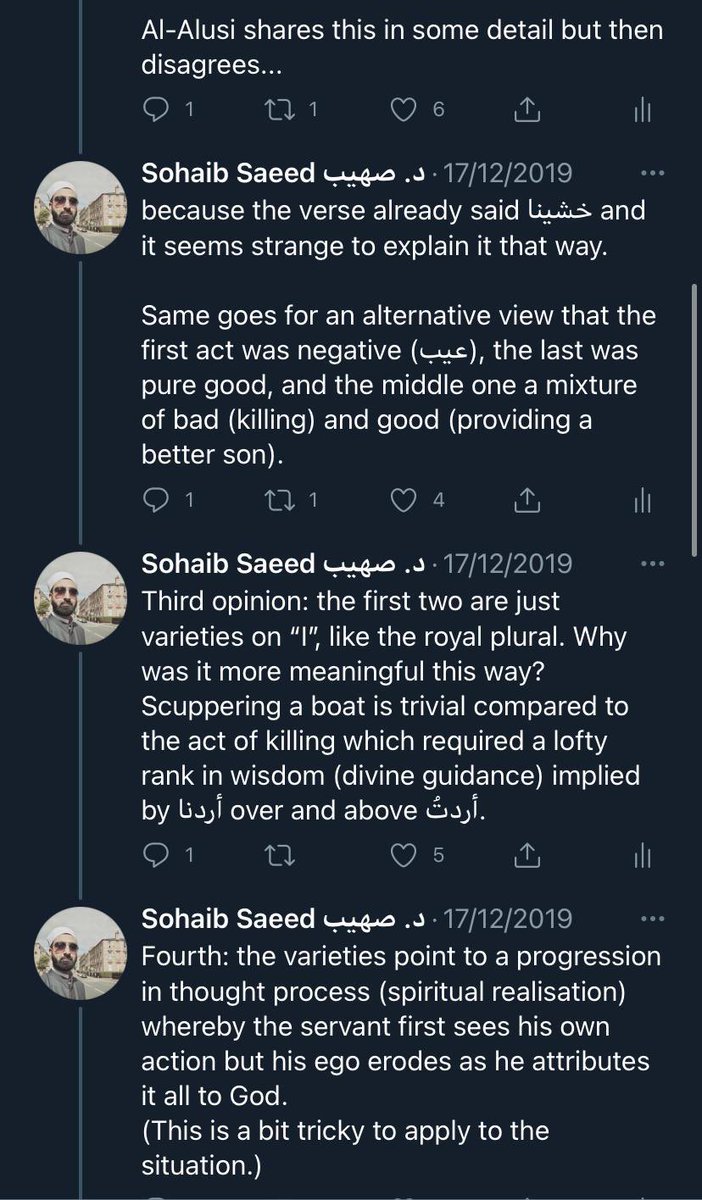

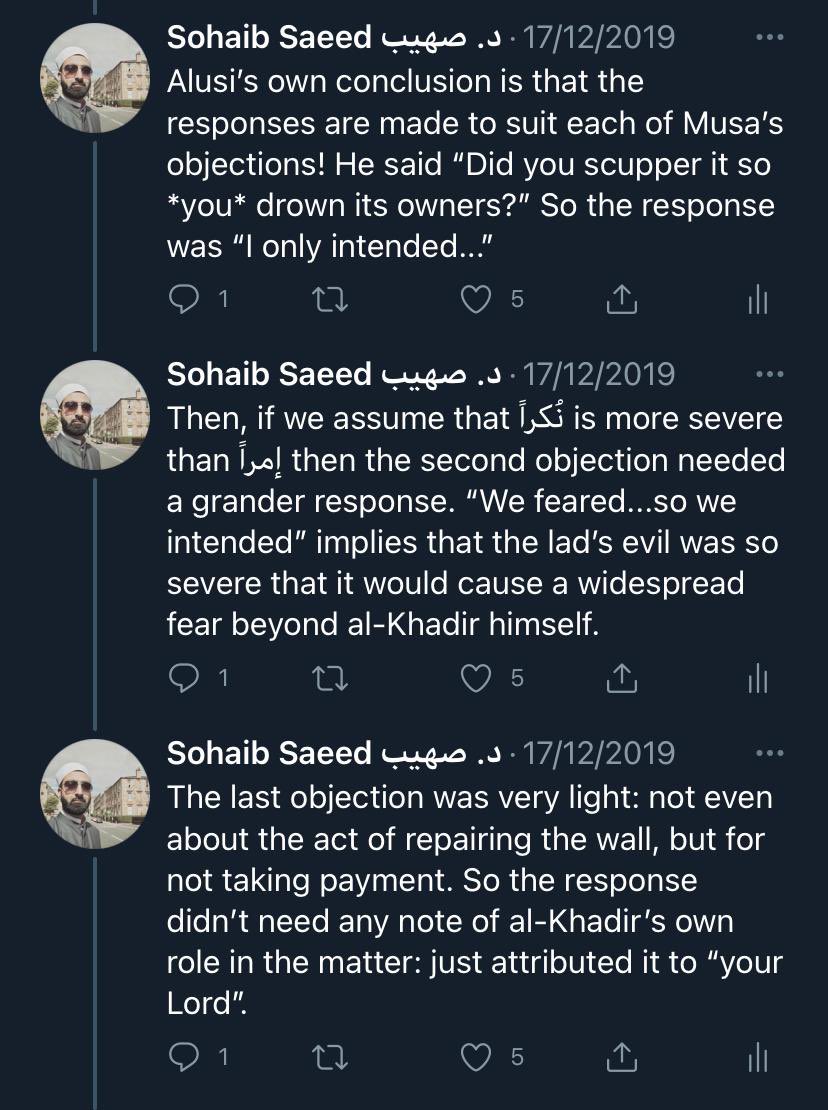

However, I must say that I’m unsatisfied with this explanation – and I didn’t find much better with my favourite mufassirs like al-Ālūsī and Ibn ʿĀshūr. Let me explain my dissatisfaction.

You see, proponents of majāz usually leave out the final logical step which I believe is necessary in tafsīr: namely, to explain why the *actual* expression is better than that provided by the mufassir by way of explanation.

So, here, the question is: why not just use a phrase that means, uncontroversially, that “it was about to fall”? What is gained by this imagery, or this roundabout phrasing which becomes a source of debate?

Here’s my take on it, building on what has already been said. The wall is being spoken of as though it were a frail old man, or just someone who has been standing for a very long time, and has now had enough…

In fact, it’s leaning over, and this leaning is causing it more pain and prolonging its suffering. It’s like someone is being tortured by being forced to stand, but after a while, they are barely standing at all…

but they’re not allowed to rest. The wall isn’t wishing for rest, so much as it’s wishing it could just be put out of its misery!

(Remember, *figuratively* – unless you’re a Shinqīṭī 😉)

(Remember, *figuratively* – unless you’re a Shinqīṭī 😉)

So, what we have here is a figure of speech that enhances our appreciation, indeed enjoyment, of the text and story. It’s more emphatic than just saying “it was about to collapse”.

So that’s where I’ll end, except that now you’re wondering about Qur’an translations. Well, apart from Palmer and Bakhtiar, it seems nobody wanted “a wall which wanted to fall to pieces” or “a wall that wants to tumble down”! 😅

islamawakened.com

islamawakened.com

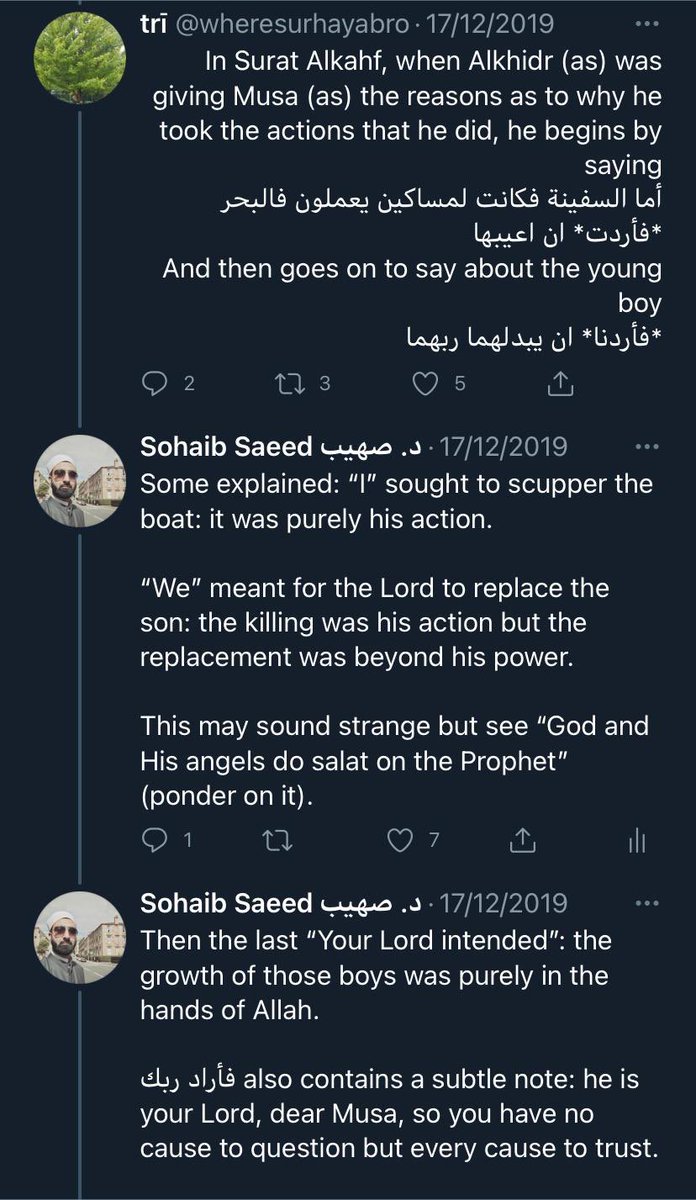

@Mustafa95653585 Beautiful observation, thanks for sharing that.

@Rejamals Tree trunk*

Yes, Sh. Shinqiti also gave examples like this. However, I disagree with the interpretation of this ayah to mean that the wall actually had consciousness and intention. Allah knows best.

Yes, Sh. Shinqiti also gave examples like this. However, I disagree with the interpretation of this ayah to mean that the wall actually had consciousness and intention. Allah knows best.

@TiredUmar @Mustafa95653585 It is certainly a thing in the Real Fuṣḥā :)

Follow-up on qira’at👇

Loading suggestions...