Methanol Gyan from Chemicals weekly -

-The single largest organic chemical imported into India is methanol. Imports in June this year was close to 300-kt. About 90% of annual

demand is imported, and operating rates at the units here have been constrained due commercial reasons.

-The single largest organic chemical imported into India is methanol. Imports in June this year was close to 300-kt. About 90% of annual

demand is imported, and operating rates at the units here have been constrained due commercial reasons.

- In recent months, there has been

an uptick in production as high prices have made it worthwhile to restart mothballed facilities.

-Methanol is most efficiently produced from gas, and economics is determined by its price.

an uptick in production as high prices have made it worthwhile to restart mothballed facilities.

-Methanol is most efficiently produced from gas, and economics is determined by its price.

There is no way gas at $12 per mBtu can

afford competitive methanol, however large the plants are or how efficiently they are run.

Globally, production is located where the gas is

available aplenty and cheap – which means the Middle East, North America and

afford competitive methanol, however large the plants are or how efficiently they are run.

Globally, production is located where the gas is

available aplenty and cheap – which means the Middle East, North America and

some parts of Latin America and the Caribbean.

The only exception is China, where coal has been used as a feedstock in large, expensive plants located close to pithead. The methanol so produced

is used as feedstock for making olefins (in particular, propylene),

The only exception is China, where coal has been used as a feedstock in large, expensive plants located close to pithead. The methanol so produced

is used as feedstock for making olefins (in particular, propylene),

and for fuel blending.

If China can do methanol at world-scale, why can’t India? The answer lies as much in the risk appetite of investors here, as in the technical

challenges of the process.

If China can do methanol at world-scale, why can’t India? The answer lies as much in the risk appetite of investors here, as in the technical

challenges of the process.

Some efforts ongoing here to make a related product – ammonia (for urea) – from coal, but this is with generous subsidies.

Don’t expect support for coal-based methanol. Imports are here to stay!

Don’t expect support for coal-based methanol. Imports are here to stay!

Methanol ( extended Gyan) ( Copy Paste from chemicals weekly)

1-Competing routes

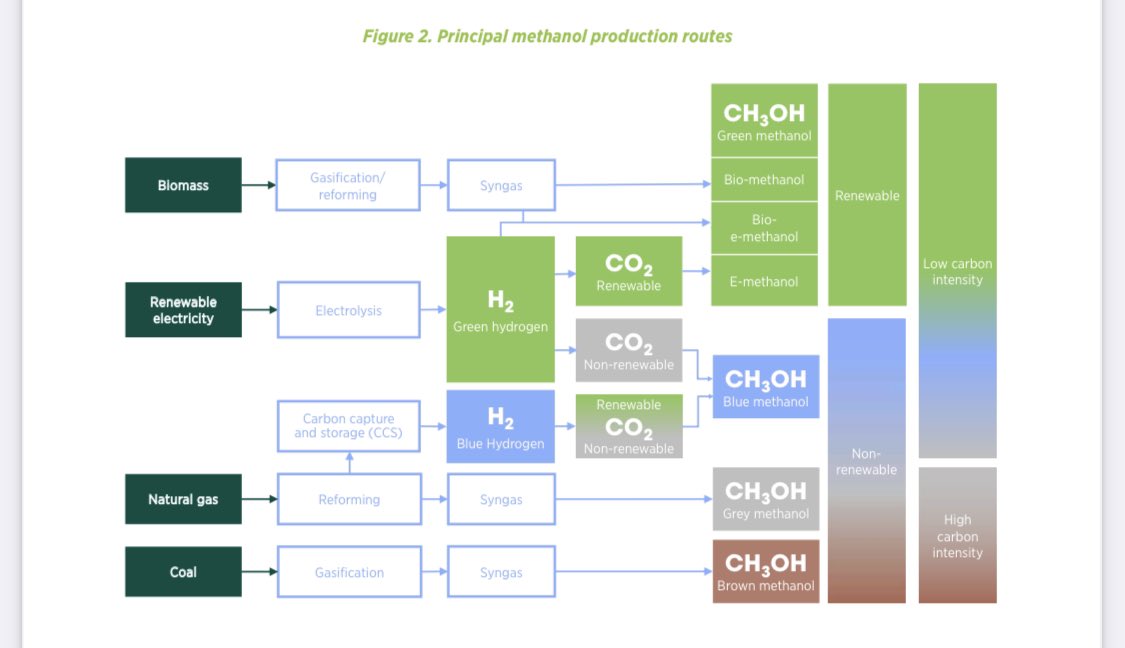

Globally, methanol is produced mostly from natural gas or coal, in a two-step process. In the first, the fuel is gasified to produce synthesis gas – a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen –

1-Competing routes

Globally, methanol is produced mostly from natural gas or coal, in a two-step process. In the first, the fuel is gasified to produce synthesis gas – a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen –

and in the second this syn gas is transformed to methanol by well established technologies.

Keeping in mind the lack of cheap gas and abundant availability of affordable coal, a significant portion of China’s methanol capacity built in the last decade has been on coal

Keeping in mind the lack of cheap gas and abundant availability of affordable coal, a significant portion of China’s methanol capacity built in the last decade has been on coal

a situation that exists nowhere else.

Likewise, much of the new gas-based capacity has

been in North America and the Middle East.

Likewise, much of the new gas-based capacity has

been in North America and the Middle East.

2-Economics of manufacture

The economics of methanol is determined by the capital cost to build a plant and the cost of operating it. The latter is all about the price of the feedstock – be it coal or gas. Gas-based plants are cheaper to build than ones on coal,

The economics of methanol is determined by the capital cost to build a plant and the cost of operating it. The latter is all about the price of the feedstock – be it coal or gas. Gas-based plants are cheaper to build than ones on coal,

but have higher operating costs.

Their relative competitiveness depends on how the fixed and operating costs add up, but over the last several years coal-based plants

have held their own, and their share of methanol production has doubled from 27% in 2010 to 54% in 2018.

Their relative competitiveness depends on how the fixed and operating costs add up, but over the last several years coal-based plants

have held their own, and their share of methanol production has doubled from 27% in 2010 to 54% in 2018.

But the coal-based plants come with a significant carbon (and water) footprint that may matter more in the future than they now, and it remains to be seen what their fate will be as China’s planners reorient industrial growth to meet carbon mitigation goals.

But for now, these plants are making all the difference to methanol availability in its largest market

3-Changed demand dynamics

The demand side for methanol has also radically changed.

3-Changed demand dynamics

The demand side for methanol has also radically changed.

Historically, the major end-uses were chemical derivatives such as acetic acid, vinyl acetate monomer, formaldehyde, dimethyl terephthalate, methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) etc.

But over the last 15 years, new

applications have set the tone, with China again being the driver.

But over the last 15 years, new

applications have set the tone, with China again being the driver.

The first dynamic has been the development and deployment in China of indigenous technology to produce olefins (ethylene and propylene) from methanol. Given that nearly three tonnes of methanol are required to produce one tonne of olefins, the impact on methanol markets has been

substantial. Methanol-to-olefin (MTO) plants are either integrated with coal-based methanol production at inland locations (near coal pitheads) or built along China’s coastline (and near markets) based on imported (gas-based) methanol.

The economics of the fully integrated coal-to-olefin (via methanol) (CTO) plants were particularly attractive in the era of high oil prices and were at the low end of the ethylene cost curve (only bettered by gas crackers in North America and the Middle East). T

This workaround has enabled China build a far greater self-reliance in polyolefins than otherwise possible.

The second dynamic that gave a spurt to global methanol demand was its use as a fuel – directly and indirectly.

The second dynamic that gave a spurt to global methanol demand was its use as a fuel – directly and indirectly.

China is one of few countries that allows methanol to be directly blended into gasoline, besides the more widespread use of MTBE as an oxygenate. There

has also been a push to use dimethyl ether (DME) as a substitute for LPG and for blending into diesel.

has also been a push to use dimethyl ether (DME) as a substitute for LPG and for blending into diesel.

4-Strong demand and prices

Thanks to these diverse drivers, methanol demand in the last decade has been growing at a CAGR of about 8% – very significant

for a chemical consumed annually at a scale of 100-mt.

Thanks to these diverse drivers, methanol demand in the last decade has been growing at a CAGR of about 8% – very significant

for a chemical consumed annually at a scale of 100-mt.

However, in 2020 demand grew just 4.3%, to about 110.9-mt – representing a relative weak year of growth, following two years of double-digit demand growth. Capacity growth has also been strong, rising by an average of 8% a year since 2010,

with the most dramatic rise seen in China and the US. Alongside mega-scale methanol plants (5,000-tpd) plants, process licensors today are offering small-scale (1,000-tpd) or giga-scale (10,000-tpd) methanol plants.

Methanol prices react to market signals and have fluctuated wildly. Average import prices into India (not inclusive of the Basic

Customs Duty of 5%), which were in the $375 per tonne range, on average in FY19, plunged to $260 in FY20 and stayed around this level

in FY21.

Customs Duty of 5%), which were in the $375 per tonne range, on average in FY19, plunged to $260 in FY20 and stayed around this level

in FY21.

In the Q1 FY22, prices recovered to the record high levels three years ago, and there is expectation that this will be sustained at least for the short-term.

This favourable price situation has permitted some of the high cost methanol plants to come back into operation,

This favourable price situation has permitted some of the high cost methanol plants to come back into operation,

and GSFC’s is one such.

India’s production of methanol represents just 7% of demand for the chemical, and the bulk of the market is served by imports.

In FY21, methanol imports were around 2.2-mt, against domestic production of under 200-kt.

India’s production of methanol represents just 7% of demand for the chemical, and the bulk of the market is served by imports.

In FY21, methanol imports were around 2.2-mt, against domestic production of under 200-kt.

The vast majority of imports came from

Saudi Arabia (835-kt), Qatar (560-kt), Oman (290-kt) and Iran (175-kt) – all regions with access to gas at prices of about $1-2 per mBtu,compared to $10-12 here.

Saudi Arabia (835-kt), Qatar (560-kt), Oman (290-kt) and Iran (175-kt) – all regions with access to gas at prices of about $1-2 per mBtu,compared to $10-12 here.

For producers in those countries, methanol serves as a way of monetizing a not-so-easily transported hydrocarbon resource into a globally traded, and easily transportable one.

India’s producers, in sharp contrast, seem to have no option but to operate in a high gas cost environment or close down. And several have chosen the latter. The plants here are also much, much smaller and these two factors combine to make for poor manufacturing

economics,

economics,

except for brief periods in the upcycle (as now). So, while the restart of the GSFC plant is welcome, its impact on the Indian methanol market will be marginal and, most likely, fleeting.

5-Building a coal-based methanol industry in India

India’s planners have been talking of building a methanol economy, in which methanol and DME play an enhanced role in serving

energy markets.

India’s planners have been talking of building a methanol economy, in which methanol and DME play an enhanced role in serving

energy markets.

Rightly, the focus has shifted to leveraging coal – a resource in seeming abundance.

But there are several challenges that need to be overcome if China’s success is to be replicated here.

But there are several challenges that need to be overcome if China’s success is to be replicated here.

These come from the nature of Indian coal, especially its high ash content, which creates all kinds of problems in the gasification section. This is the step BHEL has tackled.

But their effort, though creditable, is one baby step in a long journey to a commercial process. By its own admittance, it has taken four years for BHEL to have gotten as far as developing a prototype that can produce 0.25-tpd methanol from high ash Indian coal

using a 1.2-tpd

using a 1.2-tpd

fluidised bed gasifier. Taking it from here to a pilot or a demonstration unit that will give the validation data for building a commercial scale plant – even a small-sized one (with a capacity of 1,000-tpd) – is a giant leap of faith that few will make.

One way to mitigate the risks – as in China – is through partnerships between industry and the publicly-funded research laboratories, with government support. Keep in mind that imported technologies are expensive and projects based on them will need generous fiscal

support

support

6-Methanol economy

Methanol has transitioned from a chemical intermediate for a handful of chemicals to a fuel carrier and as an intermediate for the

two largest olefins, ethylene and propylene. This will drive markets at a pace not normally seen for a mature chemical.

Methanol has transitioned from a chemical intermediate for a handful of chemicals to a fuel carrier and as an intermediate for the

two largest olefins, ethylene and propylene. This will drive markets at a pace not normally seen for a mature chemical.

For any chemical to be an energy alternative or a blend to gasoline or diesel it must satisfy a few conditions. For one, its resource

base has to be large enough to meet requirements that could run into millions of tonnes. For another, it must fit into the infrastructure

base has to be large enough to meet requirements that could run into millions of tonnes. For another, it must fit into the infrastructure

available and find acceptance by consumers. In today’s world the environmental footprint of any alternative must also not be extensive

and certainly not worse than what it seeks to replace. Above all, it must have economic rationale under prevailing circumstances or

and certainly not worse than what it seeks to replace. Above all, it must have economic rationale under prevailing circumstances or

anticipated ones.

On several of these counts methanol does make sense, but on some it does not. While it can be produced from many raw materials –

natural gas, petroleum fractions, coal, organic biomass and even carbon dioxide,

On several of these counts methanol does make sense, but on some it does not. While it can be produced from many raw materials –

natural gas, petroleum fractions, coal, organic biomass and even carbon dioxide,

only the technologies to make it from the first three

are well-established and practiced on a large scale (though not in India).

A concerted technology development effort focused on utilisation of indigenous coal or biomass for making syngas must precede any dreams of building a

are well-established and practiced on a large scale (though not in India).

A concerted technology development effort focused on utilisation of indigenous coal or biomass for making syngas must precede any dreams of building a

methanol economy here. Some steps have been taken in this direction, but there is a long way to go!

Methanol economy in India

Loading suggestions...