That’s how Denton Cooley would respond to the quivering pleas of someone with an aneurysm of the thoracic aorta.

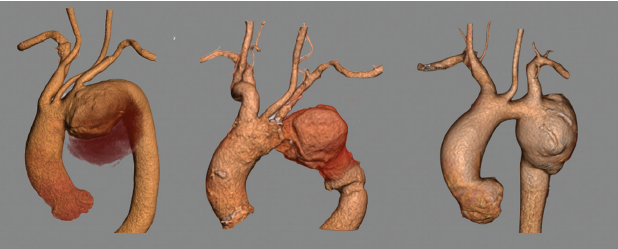

Cooley and his former boss Michael DeBakey, together, had perhaps the most extensive and unsurpassably varied experience in the matter of aneurysms.

It was Cooley who had gotten DeBakey started on the aorta.

It was Cooley who had gotten DeBakey started on the aorta.

Cooley joined the faculty of Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas) under DeBakey in 1951. On his first day, as he was tailing DeBakey and his underlings on the morning rounds, they stopped outside the door of a room.

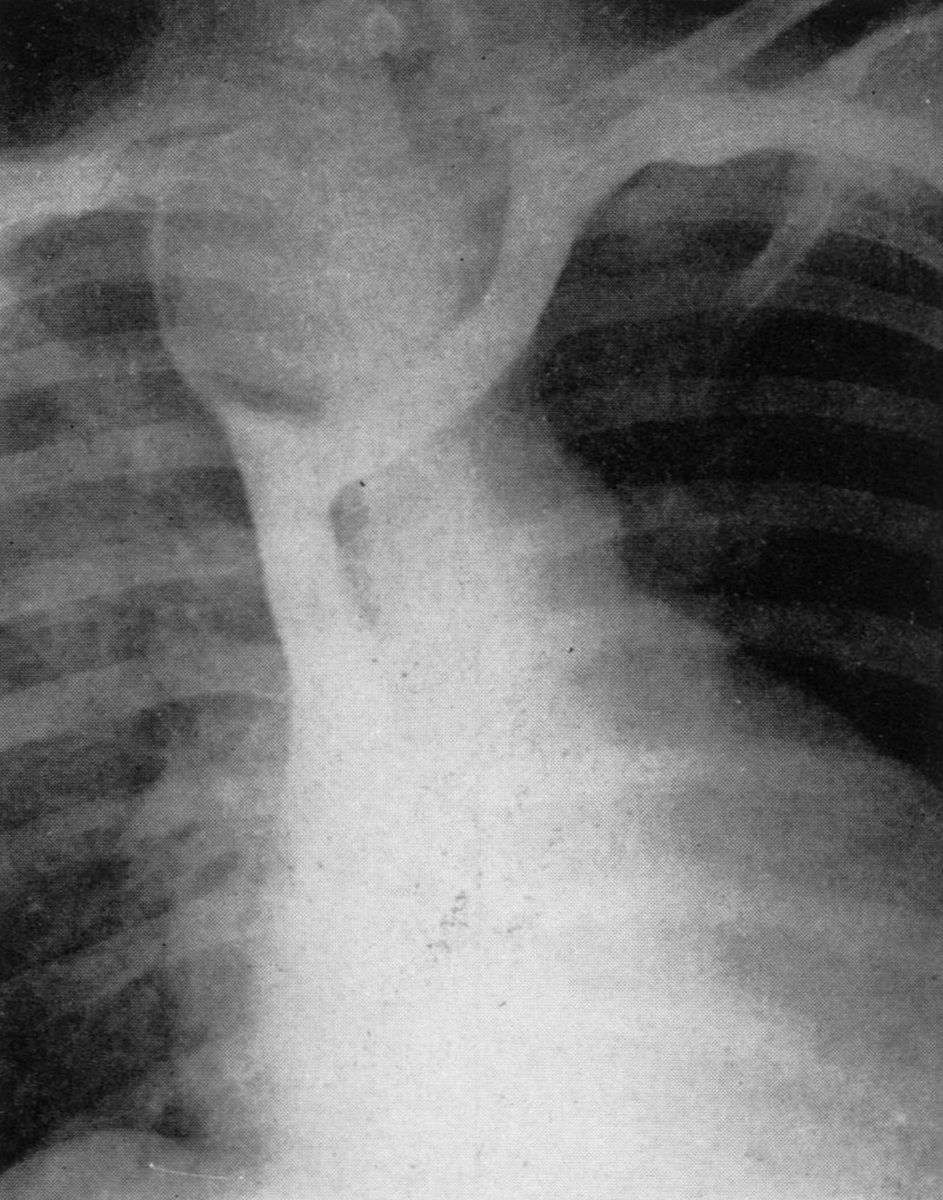

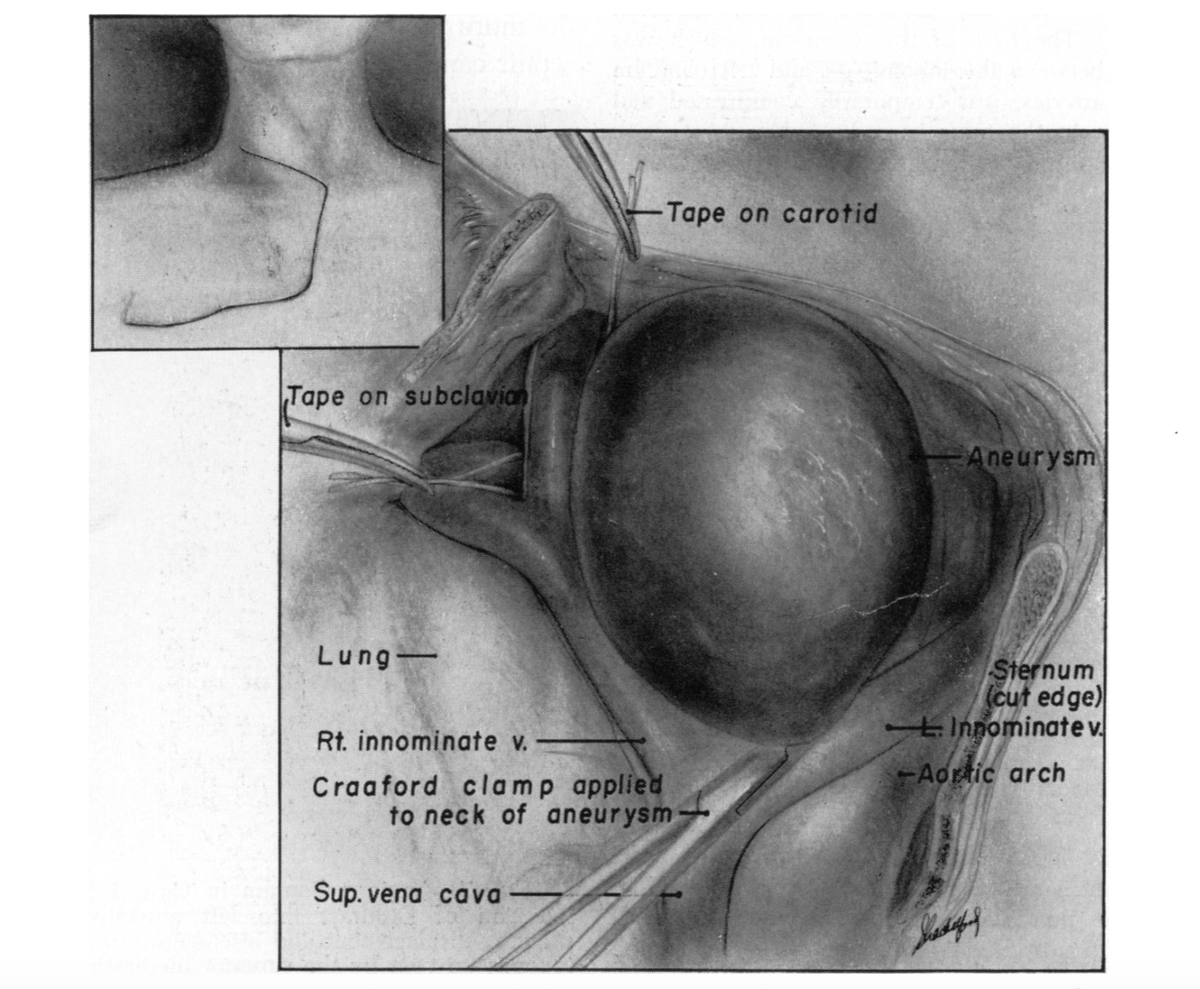

Inside lay forty-eight-year-old Joe Mitchell with a syphilitic aneurysm of the aortic arch. It had grown to become a pulsating mass above the right collarbone.

As they gathered around the patient’s bed, Debakey turned around and announced: We have a new man with us today.

Dr. Cooley, what would you do with Mr. Joe Mitchell?

“I’ll take the aneurysm out,” said Cooley. The underlings tittered.

“What exactly do you mean?” DeBakey asked

Dr. Cooley, what would you do with Mr. Joe Mitchell?

“I’ll take the aneurysm out,” said Cooley. The underlings tittered.

“What exactly do you mean?” DeBakey asked

“Well, I would put a clamp across the neck of the aneurysm, remove it, and sew the aorta back together.”

“You would remove it. And you’ve done this before?”

“You would remove it. And you’ve done this before?”

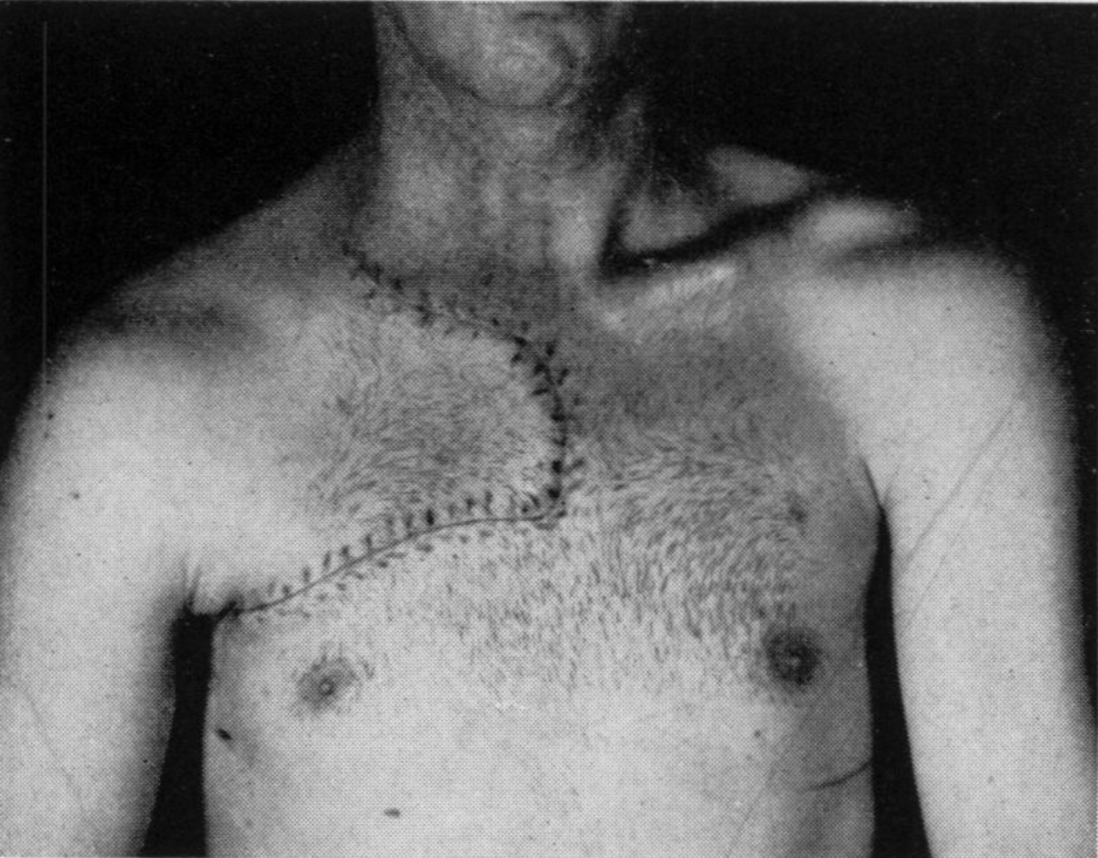

“As a matter of fact, twice.” Cooley recounted the occasions (at Johns Hopkins) when he had done something similar. As a venturesome surgical resident. Once with a colleague who held his finger in a ruptured aneurysm as he, Cooley, repaired it.

It had never been done on the aortic arch. “I think he’ll recover,” said Cooley. “He sure doesn’t have a chance lying there in bed.”

Back then, this wasn’t a standard approach, so he had to borrow a special orthopedic mallet and chisel to raise his flap.

It was possibly the first aneurysm repair of its kind to be performed anywhere in the world. DeBakey was utterly galvanized by the outcome and swayed by Cooley’s stock of skills in handling the aorta.

He was convinced that they could take on and treat other aneurysms similarly and aggressively. In the next three weeks, with DeBakey scrubbing in to watch, Cooley did three more of those aneurysms.

Later that year, DeBakey almost gloatingly presented those four cases and Cooley’s first two (Hopkins cases) at a meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Cooley, who wasn’t yet a member of the association, sat through the whole session in the audience as DeBakey blustered on animatedly about the work that he, Cooley, had done. Without even the slightest flickering mention of Cooley’s contribution.

The paper was received with great enthusiasm. DeBakey was hailed, almost instantly, as the pre-eminent aneurysm surgeon. Cooley found himself reflexively wondering if this was bad form. A rivalrous feud had begun.

For a while, as they were part of the same department, Cooley had to be, grudgingly, Marlowe to DeBakey’s Shakespeare - the vital force cum ghostwriter for all his aortic productions.

DeBakey, as chairman of the department, was the better-known surgeon. Referrals began pouring in from all over the country. Messrs DeBakey and Cooley started working side by side as full partners in consultation practice.

By 1955, between them, they had performed 245 aneurysm repairs, far surpassing any other series in volume and success. Many of them were pioneering surgical procedures of staggering complexity.

The rift between them, in the meanwhile, had grown into a yawning chasm. Though they communicated politely and avoided any direct confrontation, everyone in the surgical fraternity knew that there were no affinities between them.

Both wished Nemesis to blight the other. The awkwardness of their partnership and shared surgical practice came to an end in 1962. Cooley left DeBakey’s department and set up the Texas Heart Institute.

Years later, when Cooley stole the march on him and implanted the first totally artificial heart on a dying man, DeBakey did his best to actually call upon Nemesis.

Cooley was once asked if he felt he was a better surgeon than DeBakey. “I’ll say this, a successful cardiovascular surgeon should be someone who, when asked to name the three best surgeons in the world, would have difficulty deciding on the other two.”

“I’ve seen Dr. DeBakey operate and I consider him very able, but his personality is such that he occasionally gets rattled and loses his composure. I have a greater capacity for pressure.”

Once, during an aneurysm repair, a seventy year old man’s aorta ruptured. It was the sort of calamity his residents eagerly wished for. What would Cooley do? How would he manage this?

Wrist-deep in blood and lead only by touch, Cooley unflappably sutured the rent in the aorta. He didn’t let the man bleed to death. He was like a duck in dire straits: unruffled on the surface, paddling like the devil underneath.

“That ought to get you a chapter in the new Bible,” the first assistant remarked. “If it does,” said Cooley, “see that I’m next to Ruth in Gomorrah.”

I’ll end with a story that’s been passed from person to person as Cooley lore. While he was on his rounds, one of DeBakey’s cardiologists asked him if he could spare a moment and take a look at an x-ray. There was a suspicious shadow in the chest along the aorta.

He asked Cooley if he had seen an aneurysm in this particular area before.

“No,” said Cooley, “and neither has anyone else because that’s not an aneurysm.”

“No,” said Cooley, “and neither has anyone else because that’s not an aneurysm.”

The cardiologist hemmed and hawed and begged his pardon and added that DeBakey thought otherwise. “You can beg anything you want,” said Cooley dismissively, “but it won’t make that an aneurysm.”

“Dr. Cooley, I think you’re mistaken this time,” the cardiologist insisted. Cooley offered to bet him a hundred dollars. He declined and said that he wasn’t a betting man. “Well,” announced Cooley with an air of finality, “If that thing’s an aneurysm, I’ll eat it!”

The next morning Cooley received a phone call from the cardiologist’s secretary. “The doctor asked me to tell you to get your knife and fork ready. Do you remember the x-ray from yesterday? Dr. DeBakey just operated on him and took out an aneurysm.”

“Do me a favour,” Cooley told the secretary, “tell them to put it in alcohol, not formalin.”

“What?”

“The aneurysm.”

“What?”

“The aneurysm.”

Cooley sent one of his boys to the Chinese restaurant in the neighbourhood to fetch a tablecloth. He then phoned the in-house photography department and asked them to send their best man with a movie camera and some film lights.

A table with a red checkered tablecloth was set up in the central hall of the surgical suite.

The tableware included a glass beaker (for wine), a Bard-Parker scalpel and vascular (DeBakey) forceps.

The tableware included a glass beaker (for wine), a Bard-Parker scalpel and vascular (DeBakey) forceps.

He sat at the table, his surgical mask dangling from his neck like a bib, and asked the camera to start rolling.

The incandescent Mary Lou Budd, his favourite scrub nurse walked into the frame and placed a plate covered with an inverted steel basin in front of him. It was the kind of receptacle used to convey harvested donor hearts between ORs for transplantation.

With a flourish, she lifted the basin to reveal on the elegant silver plate “the bloody pulp of the questioned aneurysm.” She asked him to wait and then produced salt and pepper.

Cooley seasoned the aneurysm and then, quite affectedly, held the fleshy mass with DeBakey forceps, dissected off a proper chunk and ate it.

“Did you get that?” Cooley asked the man filming.

“In sixteen-millimeter colour.” said the cameraman.

“Okay. Develop it and deliver it to my cardiologist friend over at Methodist. Tell him Denton Cooley is a man of his word.”

“In sixteen-millimeter colour.” said the cameraman.

“Okay. Develop it and deliver it to my cardiologist friend over at Methodist. Tell him Denton Cooley is a man of his word.”

Loading suggestions...