[QQT: TWO LETTERS THAT MADE AN EMPIRE]

1/53

Sometime in the spring of 1583, an Englishman named John Newbery arrived in India with a letter from Elizabeth I to an Indian ruler. What happened of him after, is a tad fuzzy but it’s assumed he was robbed and killed on his way back.

1/53

Sometime in the spring of 1583, an Englishman named John Newbery arrived in India with a letter from Elizabeth I to an Indian ruler. What happened of him after, is a tad fuzzy but it’s assumed he was robbed and killed on his way back.

2/53

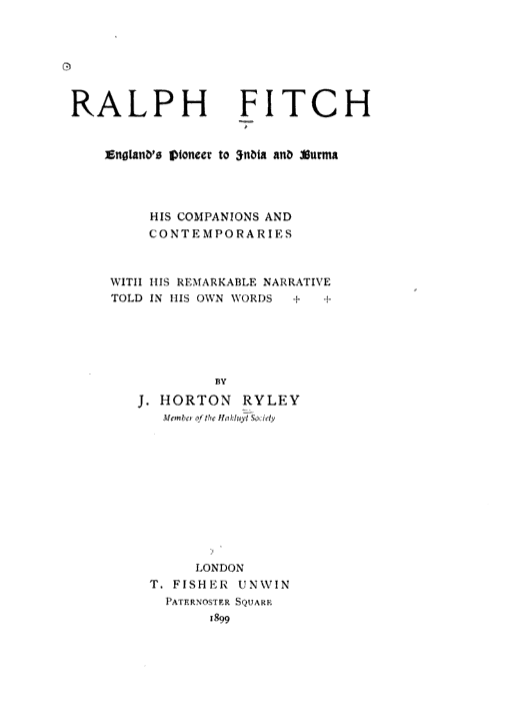

Newbery wasn’t alone. His expedition carried two merchants named Ralph Fitch and John Eldred, a jeweler named William Leeds, and a painter named James Story.

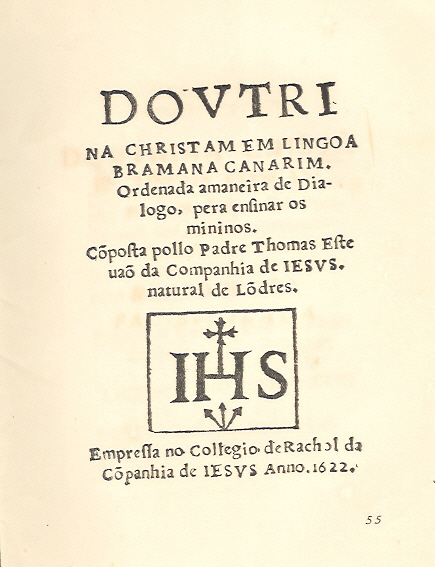

Nor was he the first Englishman in India. That credit goes to one Father Thomas Stevens of Wiltshire.

Newbery wasn’t alone. His expedition carried two merchants named Ralph Fitch and John Eldred, a jeweler named William Leeds, and a painter named James Story.

Nor was he the first Englishman in India. That credit goes to one Father Thomas Stevens of Wiltshire.

7/53

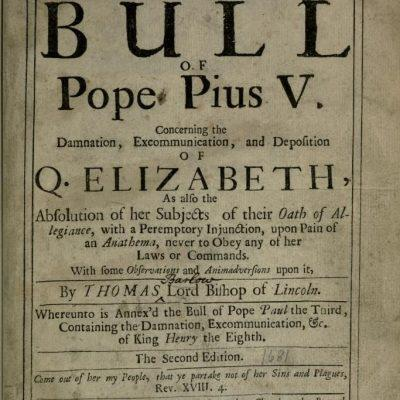

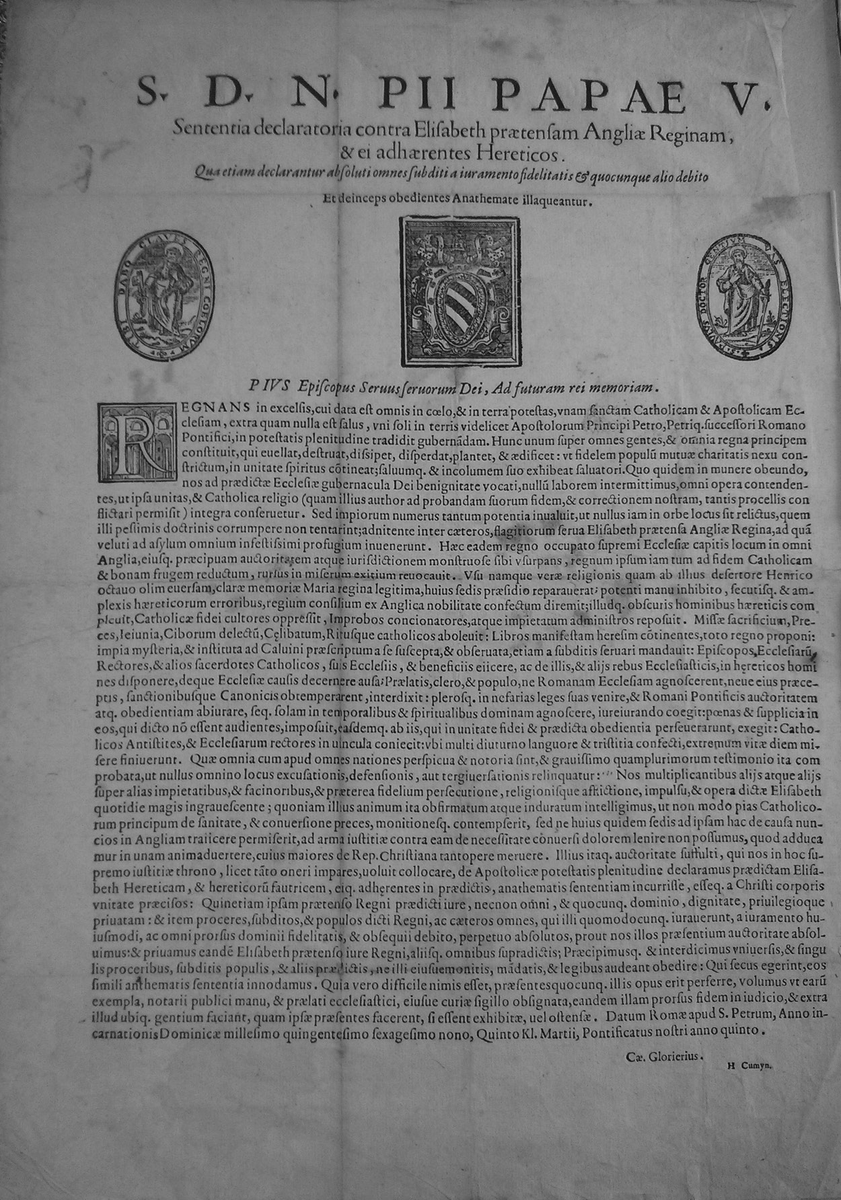

In 1534, while still a devout Catholic, Henry VIII entitled himself the “Protector and Supreme Head of the English Church and Clergy.” England was still Catholic, but no longer subservient to Rome.

And with the subsequent annulment, the first Brexit “completed.”

In 1534, while still a devout Catholic, Henry VIII entitled himself the “Protector and Supreme Head of the English Church and Clergy.” England was still Catholic, but no longer subservient to Rome.

And with the subsequent annulment, the first Brexit “completed.”

12/53

Elizabeth because Mary had died childless. The two sisters never liked each other. Elizabeth had rooted for her father, Mary for her mother. So it only follows that the new queen would endeavor to bring back the Reformation.

That’s exactly what she did.

Elizabeth because Mary had died childless. The two sisters never liked each other. Elizabeth had rooted for her father, Mary for her mother. So it only follows that the new queen would endeavor to bring back the Reformation.

That’s exactly what she did.

14/53

This time, “Brexit” came at a cost. Britain got completely isolated from Catholic Europe and the latter boycotted all business dealings with it.

In other words, Europe placed “sanctions” on Britain. The economy began to suffer. This was Rome’s clout.

This time, “Brexit” came at a cost. Britain got completely isolated from Catholic Europe and the latter boycotted all business dealings with it.

In other words, Europe placed “sanctions” on Britain. The economy began to suffer. This was Rome’s clout.

15/53

And it was tough as Elizabeth I had inherited a financially ruined kingdom. Henry VIII had left England under nearly half a million pounds of debt.

The queen had to quickly scout for new mercantile opportunities to keep her country from sinking.

And it was tough as Elizabeth I had inherited a financially ruined kingdom. Henry VIII had left England under nearly half a million pounds of debt.

The queen had to quickly scout for new mercantile opportunities to keep her country from sinking.

18/53

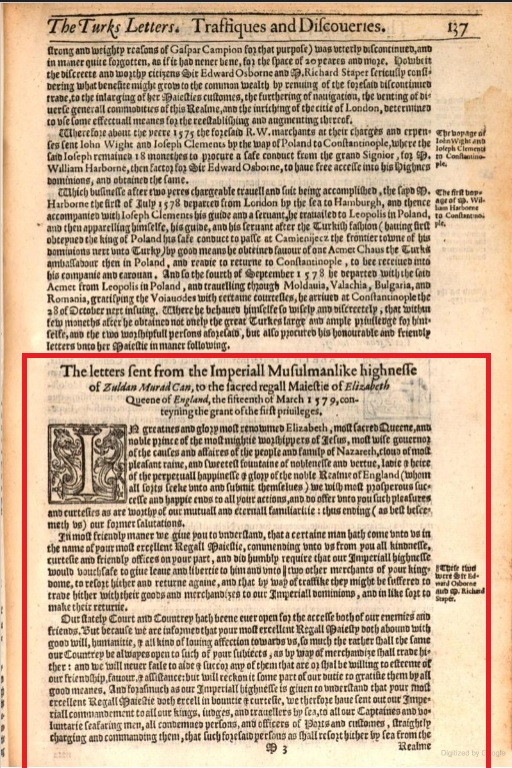

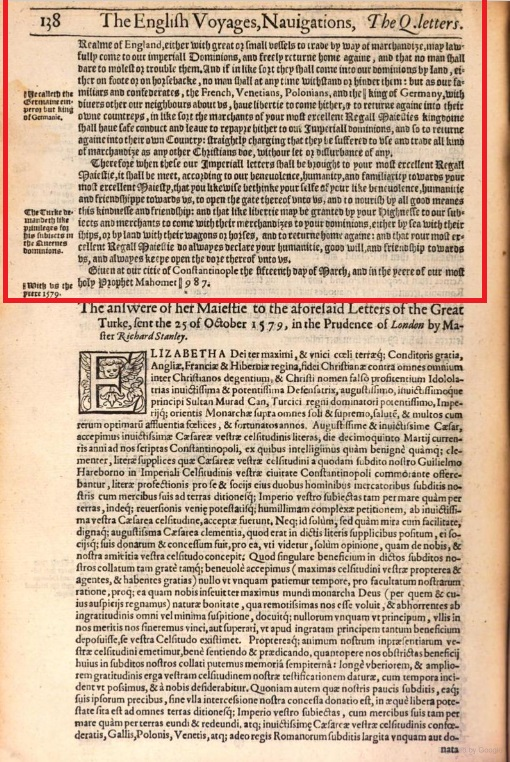

Having arrived at such a crucial juncture, the letter was more than a windfall to the struggling monarch. The queen responded promptly and kickstarted a correspondence that would last no fewer than seventeen years and help Britain avoid insolvency.

Having arrived at such a crucial juncture, the letter was more than a windfall to the struggling monarch. The queen responded promptly and kickstarted a correspondence that would last no fewer than seventeen years and help Britain avoid insolvency.

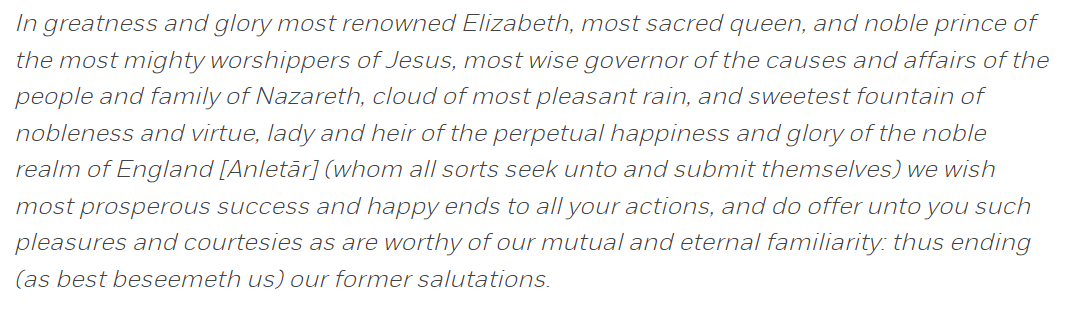

19/53

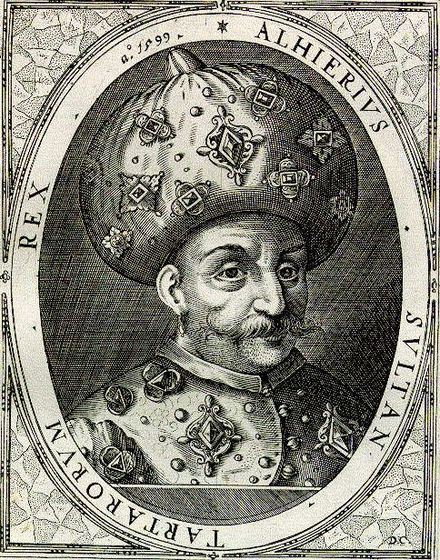

Many letters were exchanged between the two monarchs. Elizabeth wrote to him about how she and Murad both had a common adversary in Catholicism. She reminded him of the Crusades and even drew his attention to the myriad parallels between Protestantism and Islam.

Many letters were exchanged between the two monarchs. Elizabeth wrote to him about how she and Murad both had a common adversary in Catholicism. She reminded him of the Crusades and even drew his attention to the myriad parallels between Protestantism and Islam.

20/53

The two struck quite the chord. Exotic gifts were soon being exchanged and the Sultan’s wife almost became a sister to Elizabeth. The two even exchanged embassies and many Englishmen wound up in Kostantiniyye, the Ottoman capital.

The two struck quite the chord. Exotic gifts were soon being exchanged and the Sultan’s wife almost became a sister to Elizabeth. The two even exchanged embassies and many Englishmen wound up in Kostantiniyye, the Ottoman capital.

21/53

While all was going well, this relationship complicated another.

Russia.

Russia and England had been trying to work out a deal for decades now. Problem is, Turkey and Russia didn’t like each other much. This animosity went back centuries and would endure.

While all was going well, this relationship complicated another.

Russia.

Russia and England had been trying to work out a deal for decades now. Problem is, Turkey and Russia didn’t like each other much. This animosity went back centuries and would endure.

24/53

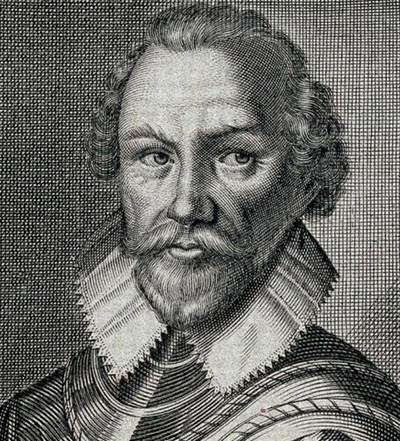

It’s under these circumstances that Anthony Jenkins, Elizabeth’s emissary in Moscow returned to England for some time.

Jenkins returned with not only a renewed trade deal but also accounts of Tatar atrocities upon the Russian people.

And a slave.

It’s under these circumstances that Anthony Jenkins, Elizabeth’s emissary in Moscow returned to England for some time.

Jenkins returned with not only a renewed trade deal but also accounts of Tatar atrocities upon the Russian people.

And a slave.

26/53

Jenkins had bought her from the Russians for, in his words, “a loaf of bread worth sixpence in England.” Brought a Muslim, Aura was quickly ordered baptized by the queen and taken in as a member of her court.

The girl would never return home.

Jenkins had bought her from the Russians for, in his words, “a loaf of bread worth sixpence in England.” Brought a Muslim, Aura was quickly ordered baptized by the queen and taken in as a member of her court.

The girl would never return home.

27/53

Over time, the Tartarian received countless gifts from the queen, each more precious than the last. There were shoes, silk gowns, damask cloaks, fur coats, gold dolls, jewelry, and lots more. Although captured as a slave in Russia, she was living it up in England.

Over time, the Tartarian received countless gifts from the queen, each more precious than the last. There were shoes, silk gowns, damask cloaks, fur coats, gold dolls, jewelry, and lots more. Although captured as a slave in Russia, she was living it up in England.

28/53

While life was now set for Aura, it was only getting complicated for her queen. Elizabeth’s mercantile dependence on an embattled Ivan was problematic. Freshly excommunicated, she needed a quick bailout.

And then came 1579.

And Murad’s letter.

While life was now set for Aura, it was only getting complicated for her queen. Elizabeth’s mercantile dependence on an embattled Ivan was problematic. Freshly excommunicated, she needed a quick bailout.

And then came 1579.

And Murad’s letter.

29/53

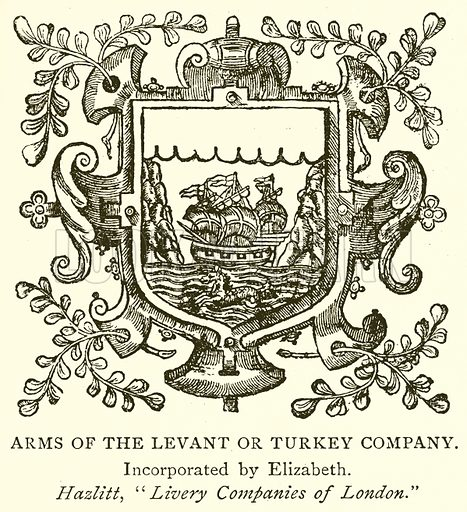

Three years after the first letter, the queen granted charter to a new company.

Trade with Turkey seemed promising, but even here she had a complication—Turkey’s relationship with Russia but we’ll come to that after a quick sidenote.

Three years after the first letter, the queen granted charter to a new company.

Trade with Turkey seemed promising, but even here she had a complication—Turkey’s relationship with Russia but we’ll come to that after a quick sidenote.

30/53

Traditionally, the Venetians had dominated all trades with Turkey. They held a virtual monopoly over all trades with the Muslim World. But both Venice and Turkey were highly territorial entities. The two had even gone to war on several occasions.

Traditionally, the Venetians had dominated all trades with Turkey. They held a virtual monopoly over all trades with the Muslim World. But both Venice and Turkey were highly territorial entities. The two had even gone to war on several occasions.

31/53

But these wars failed to affect business.

Then Venice started deteriorating. First came tariff raises and then came the infighting. Long story short, England saw an opportunity in what was increasingly beginning to look like a vacuum.

So a group of merchants moved in.

But these wars failed to affect business.

Then Venice started deteriorating. First came tariff raises and then came the infighting. Long story short, England saw an opportunity in what was increasingly beginning to look like a vacuum.

So a group of merchants moved in.

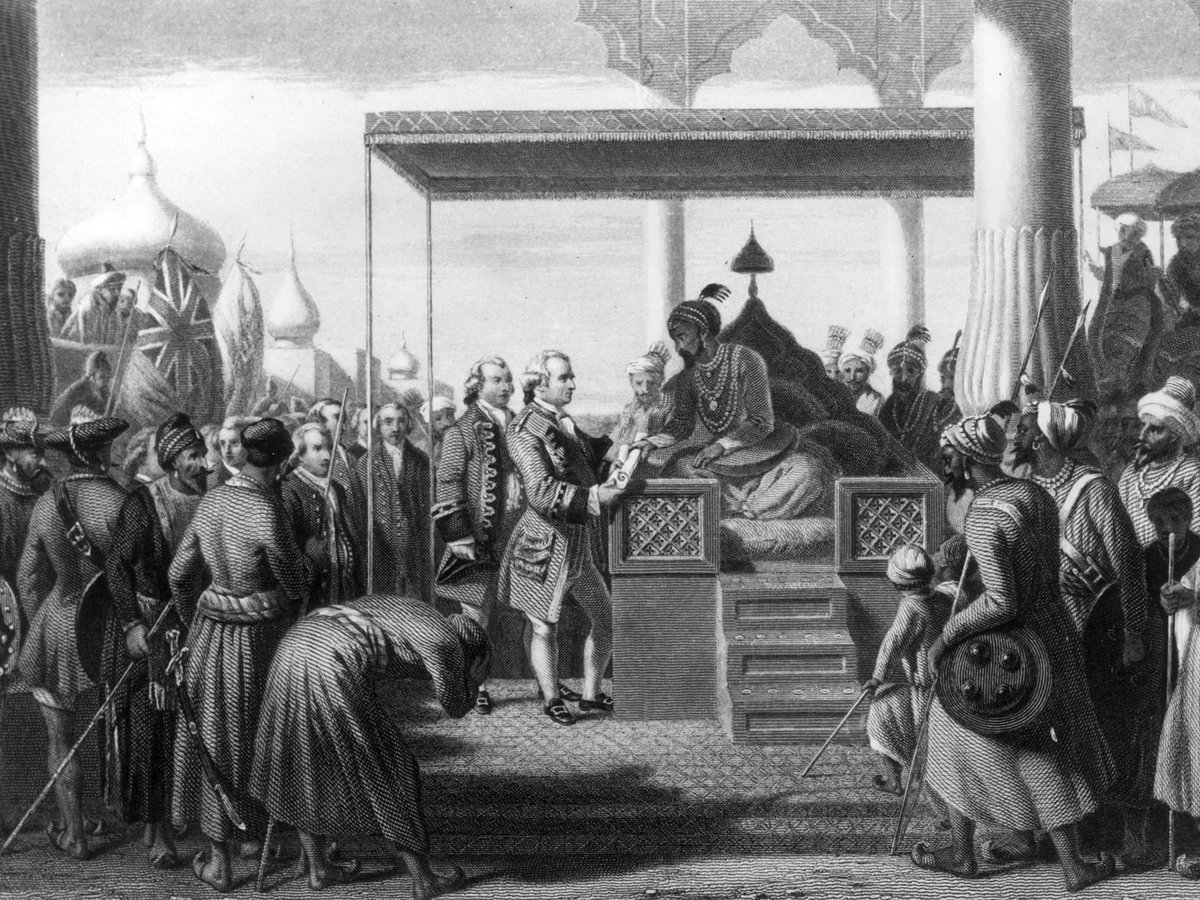

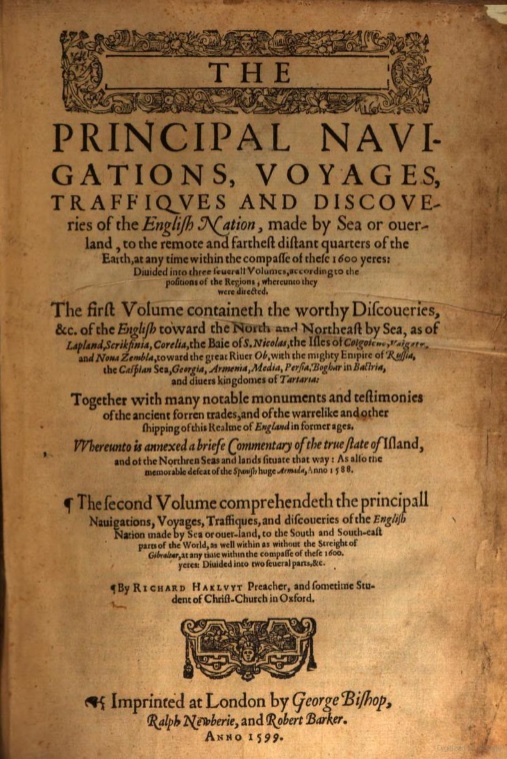

36/53

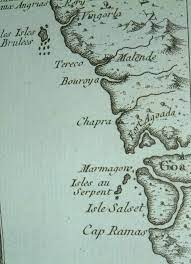

Of course, she’d also heard of Goa but it was a Portuguese bastion and being Catholic, off-limits to her men.

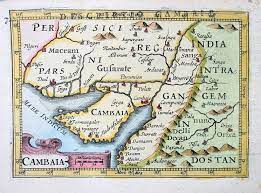

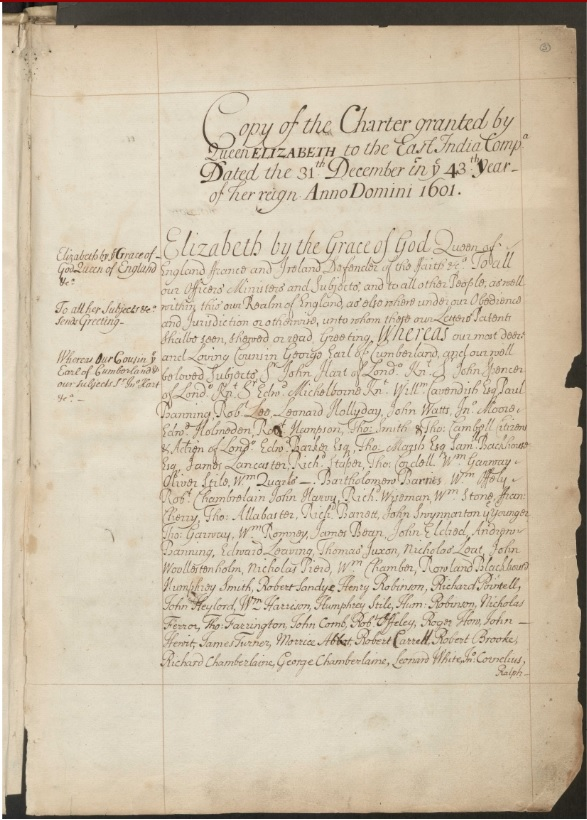

So she decided to use the voyage to scout new opportunities in this land of abundance. She wrote a letter to the king of Cambay introducing herself.

Of course, she’d also heard of Goa but it was a Portuguese bastion and being Catholic, off-limits to her men.

So she decided to use the voyage to scout new opportunities in this land of abundance. She wrote a letter to the king of Cambay introducing herself.

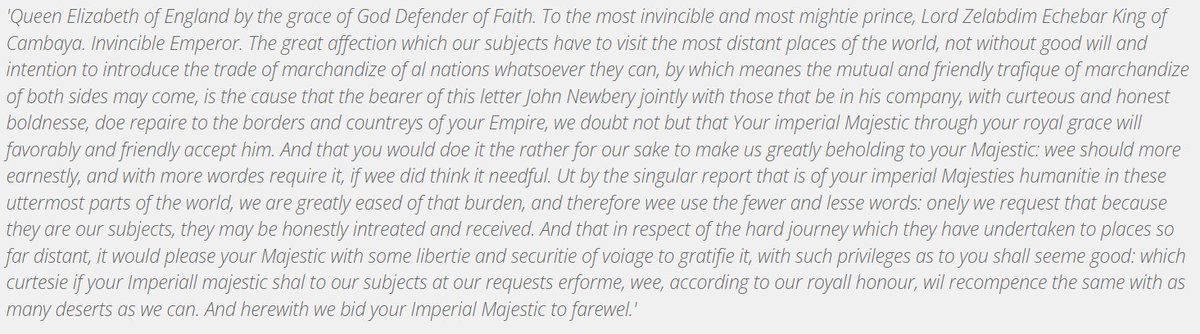

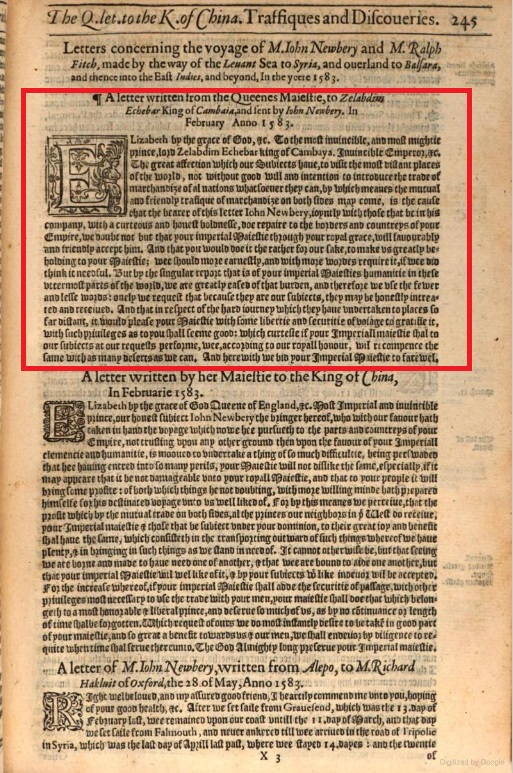

37/53

And also seeking mercantile opportunities.

This is the letter Newbery carried.

If this contact proved successful, England would become unstoppable. Elizabeth wanted to do everything in her capacity to ensure that.

The letter was as polite as it gets.

And also seeking mercantile opportunities.

This is the letter Newbery carried.

If this contact proved successful, England would become unstoppable. Elizabeth wanted to do everything in her capacity to ensure that.

The letter was as polite as it gets.

40/53

Finally they were in India!

But under extremely unfortunate circumstances. You do not want to be a Protestant prisoner in a Catholic land in the Middle Ages. Especially when your queen has just been excommunicated by the Pope himself.

This was a very dangerous position.

Finally they were in India!

But under extremely unfortunate circumstances. You do not want to be a Protestant prisoner in a Catholic land in the Middle Ages. Especially when your queen has just been excommunicated by the Pope himself.

This was a very dangerous position.

41/53

And this is where a fellow Englishman comes in. Remember Rev. Stevens, the priest from Wiltshire? He stepped in for their rescue and hired James Story the painter to paint the churches in Goa.

Story took a native wife, opened a store, and never returned home.

And this is where a fellow Englishman comes in. Remember Rev. Stevens, the priest from Wiltshire? He stepped in for their rescue and hired James Story the painter to paint the churches in Goa.

Story took a native wife, opened a store, and never returned home.

42/53

The remaining three sneaked out of Goa while on bail and traveled all over the Deccan in pursuit of trading opportunities.

I say three and not four because John Eldred had already quit the expedition while in Syria. So it was now just Newbery, Fitch, and Leeds.

The remaining three sneaked out of Goa while on bail and traveled all over the Deccan in pursuit of trading opportunities.

I say three and not four because John Eldred had already quit the expedition while in Syria. So it was now just Newbery, Fitch, and Leeds.

44/53

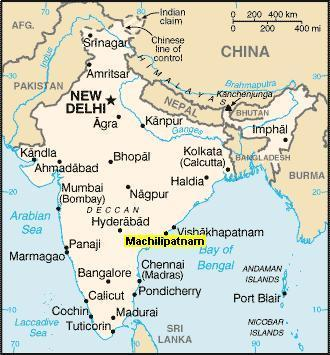

Their accounts of Masulipatnam were the reason later English merchants would pick it for their first trading outposts.

Their second discovery was that there was no king of “Cambay”!

Cambay (today, Khambat) was just part of a much larger entity, larger than even Britain!

Their accounts of Masulipatnam were the reason later English merchants would pick it for their first trading outposts.

Their second discovery was that there was no king of “Cambay”!

Cambay (today, Khambat) was just part of a much larger entity, larger than even Britain!

45/53

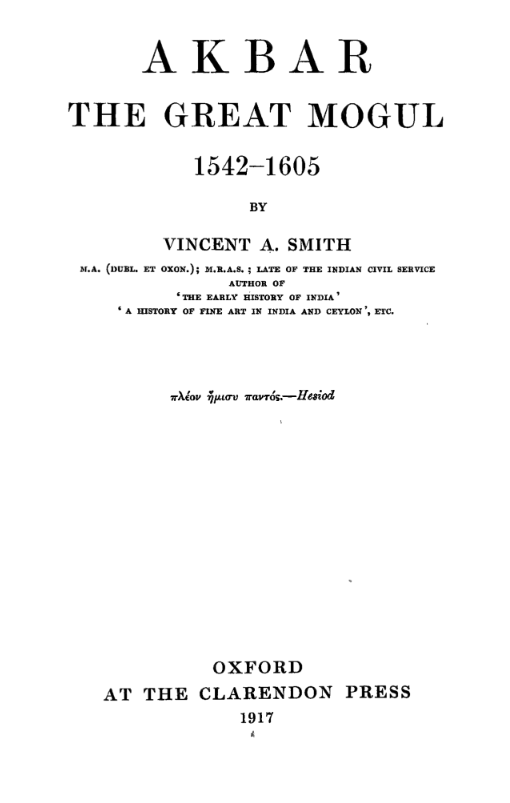

That entity was the Mughal Empire.

Interestingly, the letter was addressed to the right recipient, just with the wrong designation. What Elizabeth had thought to be the king of Cambay was actually the Emperor of India.

Once aware of their errors, the team left for Agra.

That entity was the Mughal Empire.

Interestingly, the letter was addressed to the right recipient, just with the wrong designation. What Elizabeth had thought to be the king of Cambay was actually the Emperor of India.

Once aware of their errors, the team left for Agra.

47/53

Unfortunately, only Fitch made it back as Newbery lost his way and got robbed and killed by the bandits in Sindh.

So, was the letter worth the unfortunate adventure? Did it secure Elizabeth the hedge she so desperately needed?

Unfortunately, only Fitch made it back as Newbery lost his way and got robbed and killed by the bandits in Sindh.

So, was the letter worth the unfortunate adventure? Did it secure Elizabeth the hedge she so desperately needed?

49/53

While the queen herself died before the Company set up its first Indian factory in Machilipatnam, she did manage to turn around her country’s fortunes. What she inherited as a 300,000-pound debt, was now well on its way to becoming humanity’s biggest empire ever.

While the queen herself died before the Company set up its first Indian factory in Machilipatnam, she did manage to turn around her country’s fortunes. What she inherited as a 300,000-pound debt, was now well on its way to becoming humanity’s biggest empire ever.

52/53

So this is the story of how one letter from Turkey saved Britain from bankruptcy and another to India catapulted Britain into empirehood. And all this because a king wanted to get rid of his wife. Practically, the most expensive annulment in the history of annulments.

So this is the story of how one letter from Turkey saved Britain from bankruptcy and another to India catapulted Britain into empirehood. And all this because a king wanted to get rid of his wife. Practically, the most expensive annulment in the history of annulments.

Loading suggestions...