[QQT: COOPTING PATEL]

1/33

I don’t know first-hand what the RRR gentleman really said about Patel and Nehru, but Twitter’s given a fairly decent paraphrasing thereof.

So, in a few quick tweets here, I intend to explore Patel and his relationship with both Hindutva and Nehru.

1/33

I don’t know first-hand what the RRR gentleman really said about Patel and Nehru, but Twitter’s given a fairly decent paraphrasing thereof.

So, in a few quick tweets here, I intend to explore Patel and his relationship with both Hindutva and Nehru.

2/33

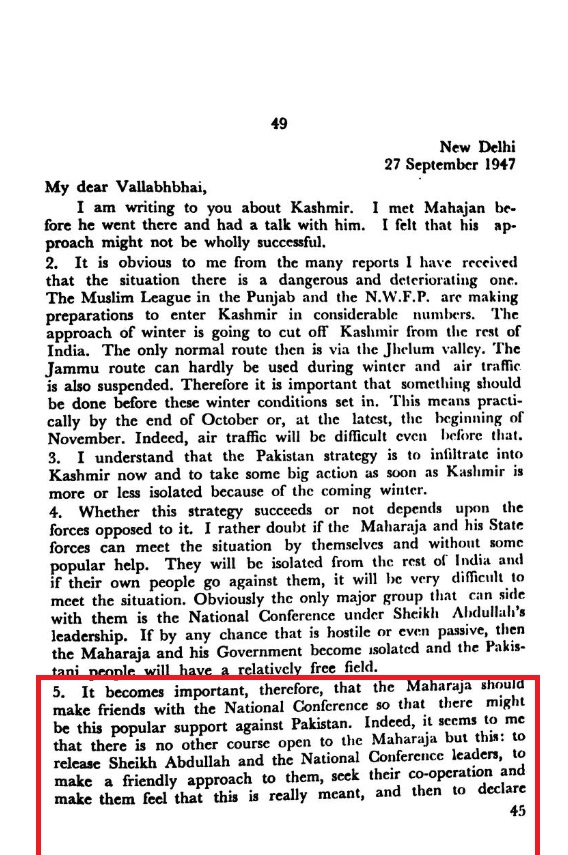

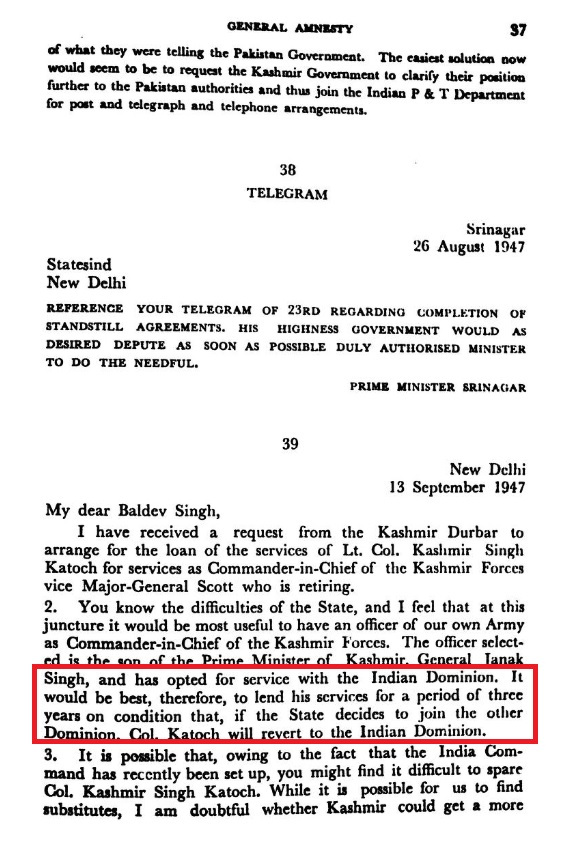

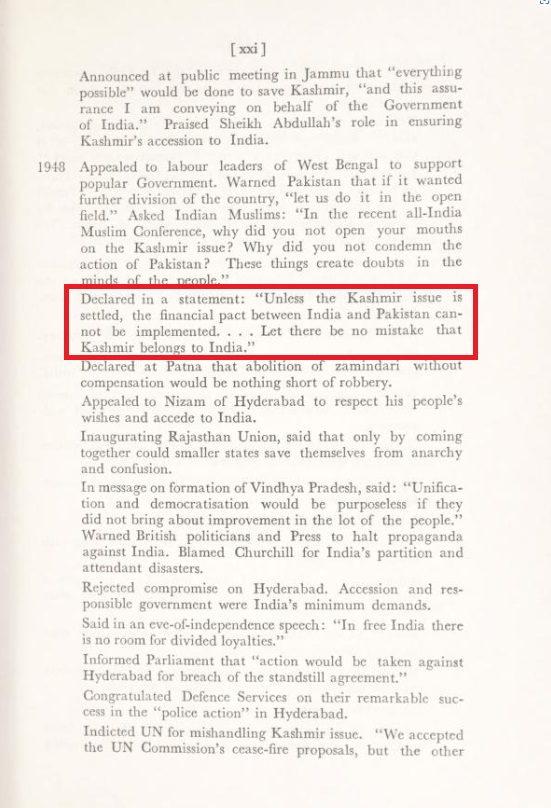

KASHMIR

Am starting with Kashmir for obvious reasons. The narrative being sold of late is that Nehru had given up Kashmir and the territory would have gone to Pakistan had Patel not intervened.

Unfortunately, history disagrees.

No, nothing wrong with Patel.

KASHMIR

Am starting with Kashmir for obvious reasons. The narrative being sold of late is that Nehru had given up Kashmir and the territory would have gone to Pakistan had Patel not intervened.

Unfortunately, history disagrees.

No, nothing wrong with Patel.

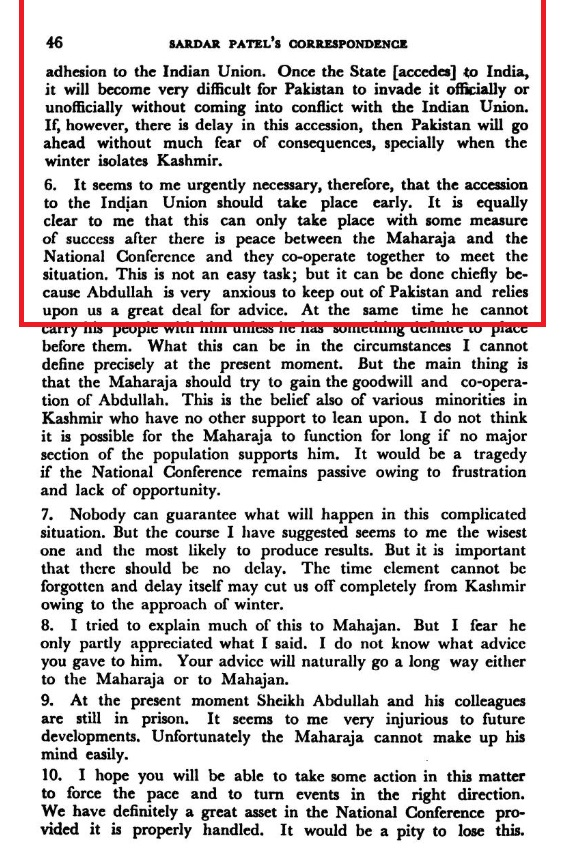

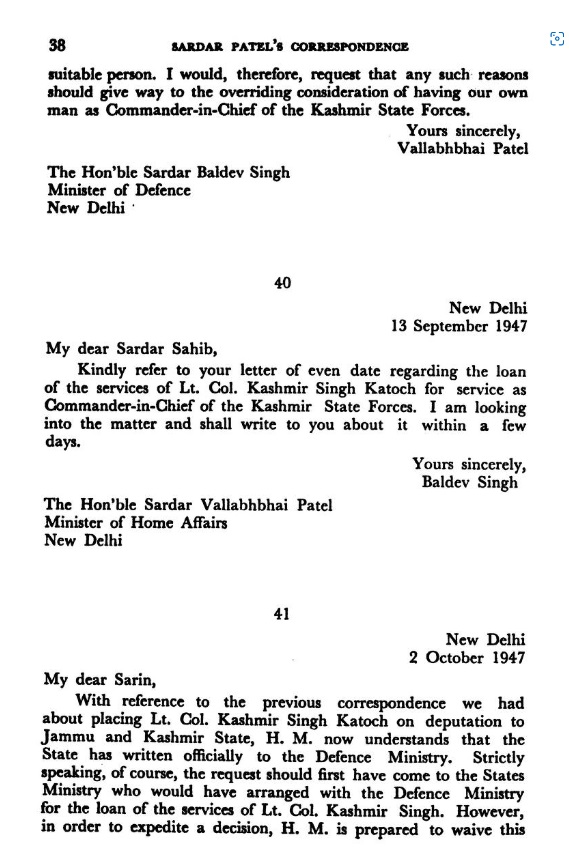

5/33

But let’s not be so sure yet. It’s just one letter. Here’s another contemporary attestation—V P Menon, who at the time as Secretary to the Government of India reported directly to Patel.

As Patel’s man, Menon was instrumental in Kashmir’s eventual ascension to India.

But let’s not be so sure yet. It’s just one letter. Here’s another contemporary attestation—V P Menon, who at the time as Secretary to the Government of India reported directly to Patel.

As Patel’s man, Menon was instrumental in Kashmir’s eventual ascension to India.

6/33

Menon had worked very closely with not only Patel, but also Nehru and Mountbatten. This makes him a crucial link between the minds of these three pivotal characters of post-Independence India. His account of Kashmir’s integration appears in his 1956 work on the subject.

Menon had worked very closely with not only Patel, but also Nehru and Mountbatten. This makes him a crucial link between the minds of these three pivotal characters of post-Independence India. His account of Kashmir’s integration appears in his 1956 work on the subject.

7/33

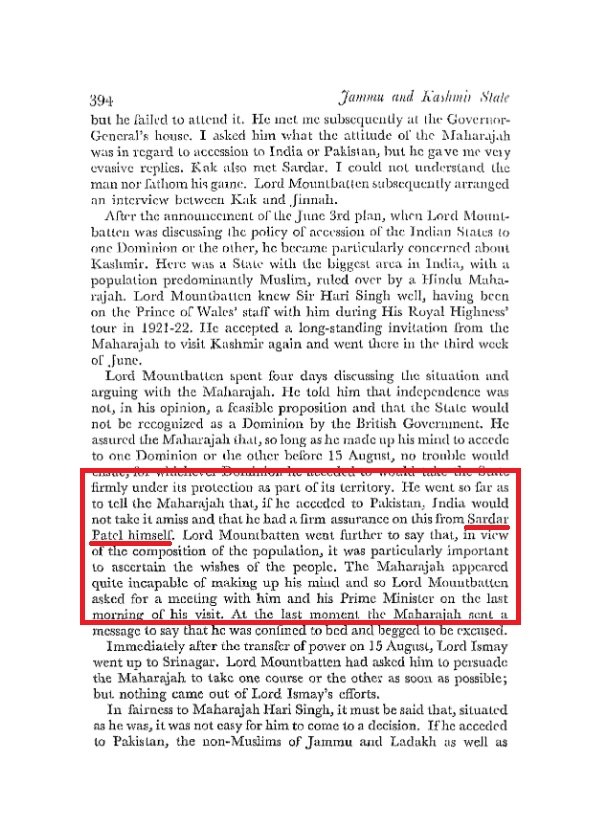

In the work (The Story of the Integration of the Indian States), Menon recounts Mountbatten’s discussions with Maharaja Hari Singh over Kashmir’s fate two months before Partition.

This was part of Mountbatten’s campaign to herd the 500-odd princely states into ascension.

In the work (The Story of the Integration of the Indian States), Menon recounts Mountbatten’s discussions with Maharaja Hari Singh over Kashmir’s fate two months before Partition.

This was part of Mountbatten’s campaign to herd the 500-odd princely states into ascension.

9/33

Do note that it’d be unfair to accuse Patel of concessions at this point as he had his reasons (read, Hyderabad). If a Muslim-majority Kashmir could go to Pakistan despite its Hindu ruler, it’d set a very useful precedent for a Hindu-majority Hyderabad with a Muslim Nizam.

Do note that it’d be unfair to accuse Patel of concessions at this point as he had his reasons (read, Hyderabad). If a Muslim-majority Kashmir could go to Pakistan despite its Hindu ruler, it’d set a very useful precedent for a Hindu-majority Hyderabad with a Muslim Nizam.

11/33

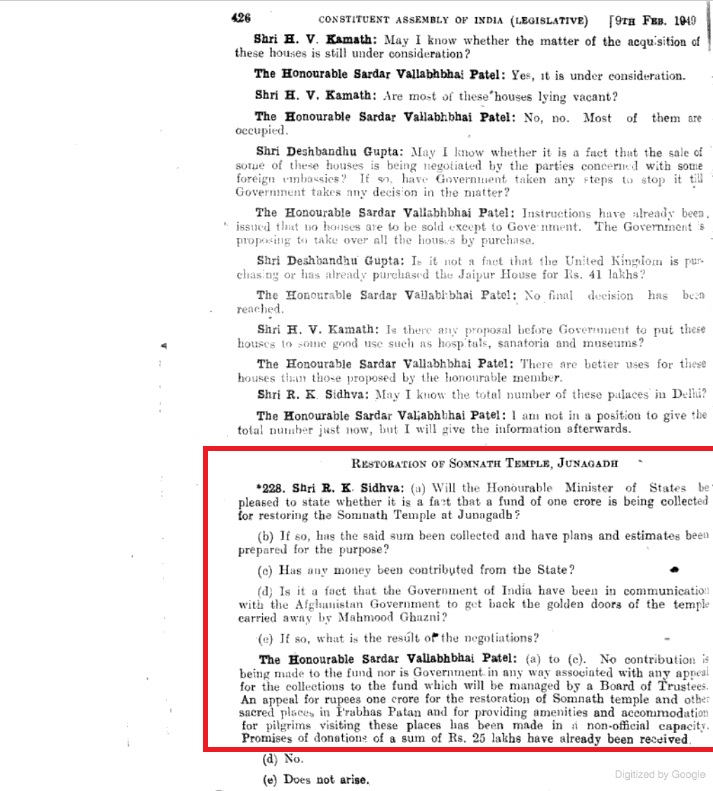

SOMNATH

Another mega-myth around Patel is his alleged Hindutva affinities. And the biggest prop for this narrative comes from none other than the temple at Somnath.

Masterstroke, indeed.

I mean what better tool than Somnath when saffronizing a Gujarati stalwart?

SOMNATH

Another mega-myth around Patel is his alleged Hindutva affinities. And the biggest prop for this narrative comes from none other than the temple at Somnath.

Masterstroke, indeed.

I mean what better tool than Somnath when saffronizing a Gujarati stalwart?

12/33

After independence, almost all princely states had chosen sides and acceded to either Pakistan or India (the only exceptions being Kashmir and Hyderabad). Among them was Junagadh.

It went to Pakistan.

Much to Patel’s discomfort.

After independence, almost all princely states had chosen sides and acceded to either Pakistan or India (the only exceptions being Kashmir and Hyderabad). Among them was Junagadh.

It went to Pakistan.

Much to Patel’s discomfort.

13/33

His reason for Junagadh was the same as his reason for Hyderabad. Just like Hyderabad, Junagadh did not share borders with Pakistan. Thus, its ascension to Pakistan would mean part of Indian territory becoming enclaved between two Pakistani territories.

His reason for Junagadh was the same as his reason for Hyderabad. Just like Hyderabad, Junagadh did not share borders with Pakistan. Thus, its ascension to Pakistan would mean part of Indian territory becoming enclaved between two Pakistani territories.

14/33

But Patel wasn’t alone. two of Junagadh’s Hindu vassals also found the idea unpalatable and rebelled. Much intrigue followed and a military action and a referendum later, Junagadh reverted to India in the spring of 1948.

With Junagadh came Somnath.

But Patel wasn’t alone. two of Junagadh’s Hindu vassals also found the idea unpalatable and rebelled. Much intrigue followed and a military action and a referendum later, Junagadh reverted to India in the spring of 1948.

With Junagadh came Somnath.

15/33

Given the communal afterglow of the Partition, the famous temple of Somnath immediately became a subject of import. Not just for its religious significance but also for its chequered history.

The Ghazni sacrilege had to be undone.

It was a question of Hindu pride.

Given the communal afterglow of the Partition, the famous temple of Somnath immediately became a subject of import. Not just for its religious significance but also for its chequered history.

The Ghazni sacrilege had to be undone.

It was a question of Hindu pride.

16/33

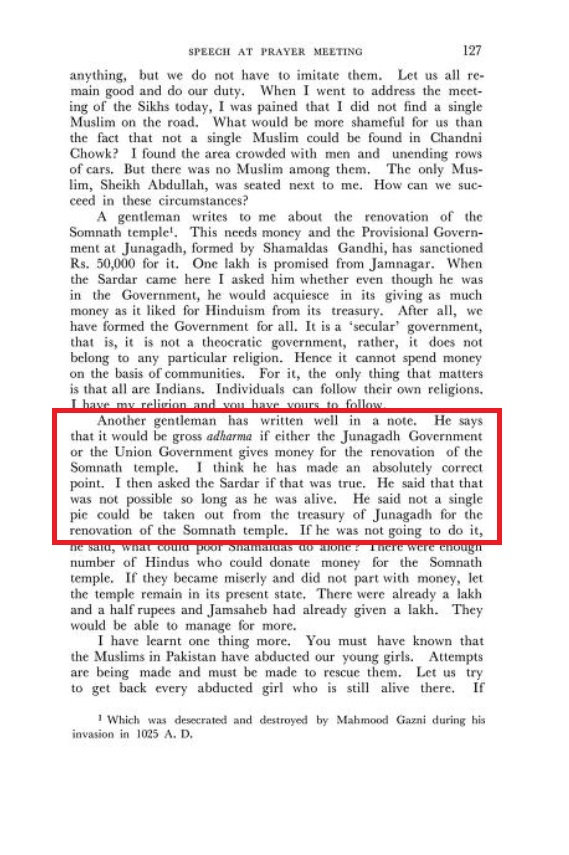

So the narrative in circulation is that Patel was keen on renovating the temple but Nehru objected.

But once again, history disagrees.

Not with Patel’s role, but with Nehru’s. It’s true that Patel wanted to restore the temple to its ancient glory. But…

So the narrative in circulation is that Patel was keen on renovating the temple but Nehru objected.

But once again, history disagrees.

Not with Patel’s role, but with Nehru’s. It’s true that Patel wanted to restore the temple to its ancient glory. But…

17/33

Patel’s secularism was absolute. We know this because he is the one who refused to sanction government funds for the restoration.

India being secular, he reasoned, it’d be wrong for the government to spend money on religious structures of one community.

Patel’s secularism was absolute. We know this because he is the one who refused to sanction government funds for the restoration.

India being secular, he reasoned, it’d be wrong for the government to spend money on religious structures of one community.

20/33

PRESIDENCY

The third area of contention that exists between the Indian Left and Indian Right is with regards to Gandhi’s biases toward Nehru, especially in the context of Congress’ presidency.

This is particularly with reference to the Lahore session of 1929.

PRESIDENCY

The third area of contention that exists between the Indian Left and Indian Right is with regards to Gandhi’s biases toward Nehru, especially in the context of Congress’ presidency.

This is particularly with reference to the Lahore session of 1929.

21/33

This session was a landmark in the story of India in more ways than one. For starters, this is the session where, on New Year’s Eve, the Indian Tricolor was raised for the first time ever.

The hoisting was done by the Congress president of the time, Nehru.

This session was a landmark in the story of India in more ways than one. For starters, this is the session where, on New Year’s Eve, the Indian Tricolor was raised for the first time ever.

The hoisting was done by the Congress president of the time, Nehru.

22/33

And that brings us to the third point making this event a historical landmark—Nehru’s promotion to the party’s presidency.

By the way, this is also the session where India’s independence was formally declared. The date chosen was Jan 26, 1930. But I digress.

And that brings us to the third point making this event a historical landmark—Nehru’s promotion to the party’s presidency.

By the way, this is also the session where India’s independence was formally declared. The date chosen was Jan 26, 1930. But I digress.

23/33

So Nehru’s promotion. This is the bone of contention. And the fount of bitter narratives.

Gandhi had a choice between Patel and Nehru and it’s said he picked the latter. Many read this as an inherent bias for obvious reasons. But is that true?

Let’s ask Gandhi himself!

So Nehru’s promotion. This is the bone of contention. And the fount of bitter narratives.

Gandhi had a choice between Patel and Nehru and it’s said he picked the latter. Many read this as an inherent bias for obvious reasons. But is that true?

Let’s ask Gandhi himself!

24/33

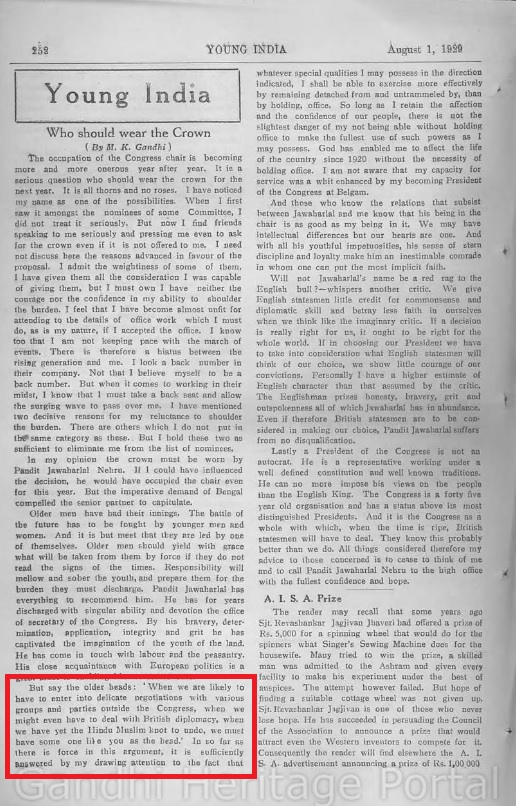

Those days, Gandhi published a weekly mouthpiece to air his thoughts and general Congress news to the public at large—Young India.

This is the magazine where our answer lies; in the August 1, 1929 issue. Here, Gandhi has done a whole article explaining his choice.

Those days, Gandhi published a weekly mouthpiece to air his thoughts and general Congress news to the public at large—Young India.

This is the magazine where our answer lies; in the August 1, 1929 issue. Here, Gandhi has done a whole article explaining his choice.

25/33

Note that this article came out nearly five months before the Lahore session, so the choice had been deliberated upon that far in advance.

Here, Gandhi says he needed someone young and dynamic to rally the Muslim masses around a common cause with the Hindus.

Note that this article came out nearly five months before the Lahore session, so the choice had been deliberated upon that far in advance.

Here, Gandhi says he needed someone young and dynamic to rally the Muslim masses around a common cause with the Hindus.

26/33

Don’t forget that this was a difficult time for India’s unity. Only the previous year at the Calcutta session (1928), Jinnah had expressed his “parting of ways” with the Congress over Muslim representation in the envisioned Indian Dominion.

Don’t forget that this was a difficult time for India’s unity. Only the previous year at the Calcutta session (1928), Jinnah had expressed his “parting of ways” with the Congress over Muslim representation in the envisioned Indian Dominion.

27/33

And Jinnah was a charismatic leader. Suddenly large numbers of Muslims were leaving Congress for Jinnah’s more radical politics. This was not good for India. There were no talks of partition at the time, but a divided India was still a threat to the freedom movement.

And Jinnah was a charismatic leader. Suddenly large numbers of Muslims were leaving Congress for Jinnah’s more radical politics. This was not good for India. There were no talks of partition at the time, but a divided India was still a threat to the freedom movement.

29/33

The Calcutta session didn’t witness just the friction between Jinnah and Congress, but also one between Congress and Nehru himself.

Gandhi and other seniors were willing to contend with India being a dominion under British rule.

Nehru rejected this.

Vehemently.

The Calcutta session didn’t witness just the friction between Jinnah and Congress, but also one between Congress and Nehru himself.

Gandhi and other seniors were willing to contend with India being a dominion under British rule.

Nehru rejected this.

Vehemently.

30/33

On Nehru’s side was none other than Bose. This was another reason Gandhi wanted Nehru in a position of responsibility. The party was staring at two splits which would be disastrous for self-rule.

So, Nehru’s elevation was to counter Jinnah as much as to counter himself.

On Nehru’s side was none other than Bose. This was another reason Gandhi wanted Nehru in a position of responsibility. The party was staring at two splits which would be disastrous for self-rule.

So, Nehru’s elevation was to counter Jinnah as much as to counter himself.

33/33

All this is not to say that Nehru and Patel never had disagreements; the two were 14 years apart, for heaven’s sake!

But to extrapolate such contentions, natural to two highly opinionated men in politics, into something sinister and conspiratorial?

That’s mischievous.

All this is not to say that Nehru and Patel never had disagreements; the two were 14 years apart, for heaven’s sake!

But to extrapolate such contentions, natural to two highly opinionated men in politics, into something sinister and conspiratorial?

That’s mischievous.

Further on the question of Congress’ “nepotism” in 1929…

Loading suggestions...