4/

Even centuries ago, "area" and "perimeter" were vital concepts.

For example, if you had a farm and wanted to estimate how much crop it would yield, you'd calculate the farm's *area*.

But if you wanted to build a fence around the farm, you'd calculate its *perimeter*.

Even centuries ago, "area" and "perimeter" were vital concepts.

For example, if you had a farm and wanted to estimate how much crop it would yield, you'd calculate the farm's *area*.

But if you wanted to build a fence around the farm, you'd calculate its *perimeter*.

6/

A circle, of course, is one of the most natural and symmetric curved shapes.

So, mathematicians tried for centuries to crack its area and perimeter.

Finally, ~2400 years ago, a Greek mathematician made some headway. His name was Eudoxus.

A circle, of course, is one of the most natural and symmetric curved shapes.

So, mathematicians tried for centuries to crack its area and perimeter.

Finally, ~2400 years ago, a Greek mathematician made some headway. His name was Eudoxus.

8/

In the illustration above, we initially cut up the circle into 12 slivers.

But Eudoxus realized he could go much further.

He could cut up the circle into 24, or 48, or 96, or 1 million slivers!

In the illustration above, we initially cut up the circle into 12 slivers.

But Eudoxus realized he could go much further.

He could cut up the circle into 24, or 48, or 96, or 1 million slivers!

9/

The more slivers Eudoxus used, the "closer" his final shape got to this "mythical" rectangle -- with width C/2 and height r.

But no matter how many slivers, the shape's area always equaled the circle's area A.

After all, the slivers came from cutting up the circle.

The more slivers Eudoxus used, the "closer" his final shape got to this "mythical" rectangle -- with width C/2 and height r.

But no matter how many slivers, the shape's area always equaled the circle's area A.

After all, the slivers came from cutting up the circle.

10/

Eudoxus realized there's only one way to reconcile this:

The circle's area has to be *exactly* (C/2) * r.

Thus, A = (C/2) * r.

This was a landmark moment for math. For the first time, an infinite "cutting up" process was used to reason about a finite thing like a circle.

Eudoxus realized there's only one way to reconcile this:

The circle's area has to be *exactly* (C/2) * r.

Thus, A = (C/2) * r.

This was a landmark moment for math. For the first time, an infinite "cutting up" process was used to reason about a finite thing like a circle.

11/

Notice we've said nothing about pi so far.

All we know so far is: A = (C/2) * r.

We don't yet know that A = pi * (r^2) or that C = 2 * pi * r.

It took another great Greek mathematician -- Euclid -- to piece that together.

Notice we've said nothing about pi so far.

All we know so far is: A = (C/2) * r.

We don't yet know that A = pi * (r^2) or that C = 2 * pi * r.

It took another great Greek mathematician -- Euclid -- to piece that together.

17/

So, we have our famous area and circumference (perimeter) formulas that use pi:

A = pi * (r ^ 2) and C = 2 * pi * r.

But so far, we've said nothing about how *big* pi is.

We don't know it's approximately 22/7.

Enter Archimedes -- our third great Greek mathematician.

So, we have our famous area and circumference (perimeter) formulas that use pi:

A = pi * (r ^ 2) and C = 2 * pi * r.

But so far, we've said nothing about how *big* pi is.

We don't know it's approximately 22/7.

Enter Archimedes -- our third great Greek mathematician.

19/

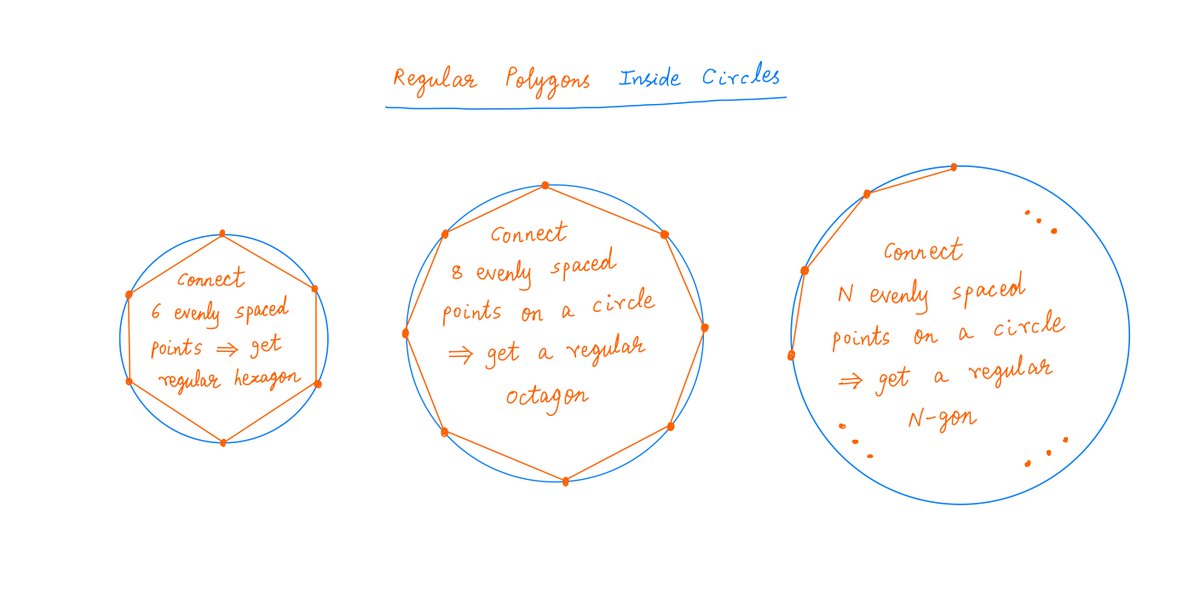

We can use this "Archimedes sandwich" to approximate pi as closely as we like.

It's how Archimedes got 22/7.

Again, the nub is in increasing our N.

As we take N higher, our outer and inner N-gons come closer -- *always* keeping the circle sandwiched between them.

We can use this "Archimedes sandwich" to approximate pi as closely as we like.

It's how Archimedes got 22/7.

Again, the nub is in increasing our N.

As we take N higher, our outer and inner N-gons come closer -- *always* keeping the circle sandwiched between them.

21/

The only part of this approximation scheme we haven't covered is how to calculate a_N and b_N -- the sides of our inner and outer N-gons.

Archimedes solved this brilliantly.

He developed what computer scientists today call an "iterative algorithm" to find a_N and b_N.

The only part of this approximation scheme we haven't covered is how to calculate a_N and b_N -- the sides of our inner and outer N-gons.

Archimedes solved this brilliantly.

He developed what computer scientists today call an "iterative algorithm" to find a_N and b_N.

26/

I'll leave you with a few resources to learn more.

Prof. Steven Strogatz's outstanding book, Infinite Powers, contains some pi history.

It's also a lovely introduction to calculus -- for non-mathematicians.

(h/t @stevenstrogatz)

amazon.com

I'll leave you with a few resources to learn more.

Prof. Steven Strogatz's outstanding book, Infinite Powers, contains some pi history.

It's also a lovely introduction to calculus -- for non-mathematicians.

(h/t @stevenstrogatz)

amazon.com

27/

This ~18 minute video by @veritasium beautifully describes how Isaac Newton discovered a completely new method to calculate pi -- one that's far more powerful than Archimedes's.

youtube.com

This ~18 minute video by @veritasium beautifully describes how Isaac Newton discovered a completely new method to calculate pi -- one that's far more powerful than Archimedes's.

youtube.com

28/

We often see headlines like:

"New research calculates pi to X trillion digits"

If you're curious about the methods these researchers use to find so many digits of pi, read this book: Pi Unleashed.

amazon.com

We often see headlines like:

"New research calculates pi to X trillion digits"

If you're curious about the methods these researchers use to find so many digits of pi, read this book: Pi Unleashed.

amazon.com

Loading suggestions...