Since its emergence in late 2019, #SARSCoV2 has diversified into multiple distinct variants.

In a new preprint, I quantify evolution within these variants and compare it to the process that gave rise to these variants.

biorxiv.org

1/N

In a new preprint, I quantify evolution within these variants and compare it to the process that gave rise to these variants.

biorxiv.org

1/N

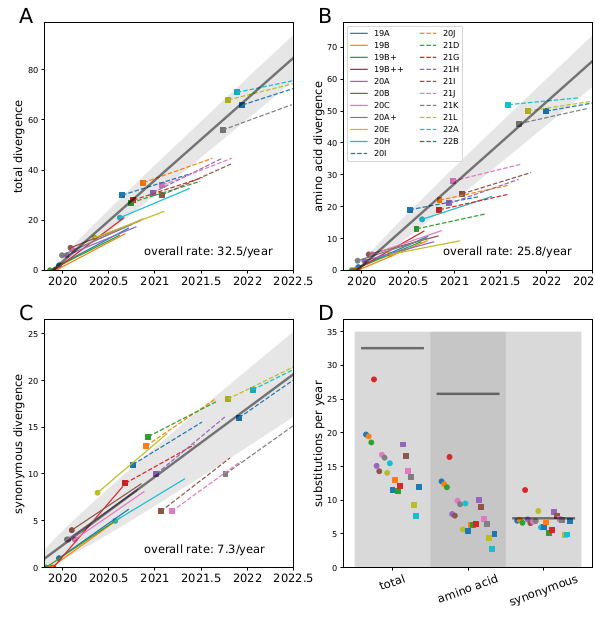

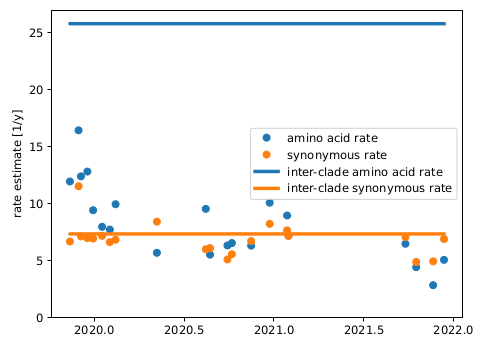

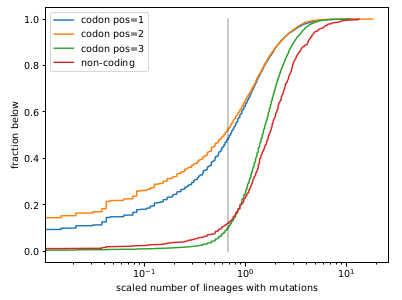

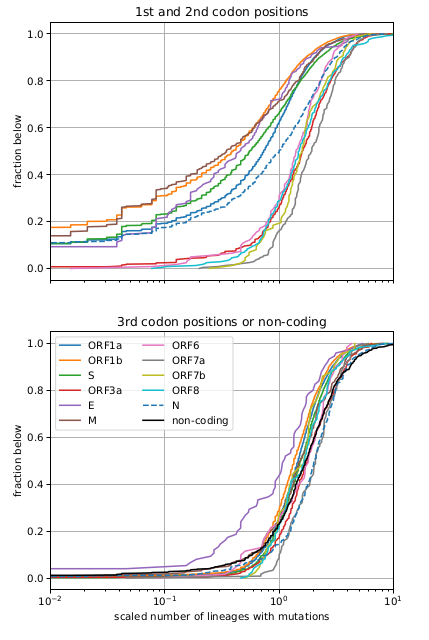

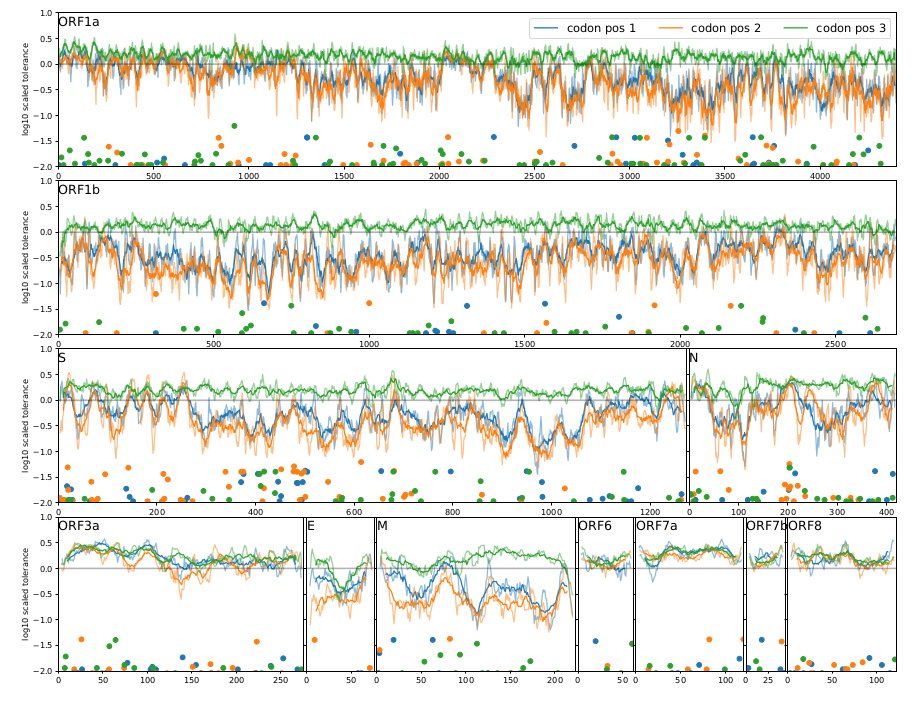

Remarkably, all variants we observed to date are compatible with a back-bone evolutionary rate of about 30 changes per year (0.001/site/year), while the within-variant rate is around 12/year (0.004/site/year).

4/N

4/N

Since the synonymous rate doesn't change, this has likely more to do with selection than intrinsic mutation rate.

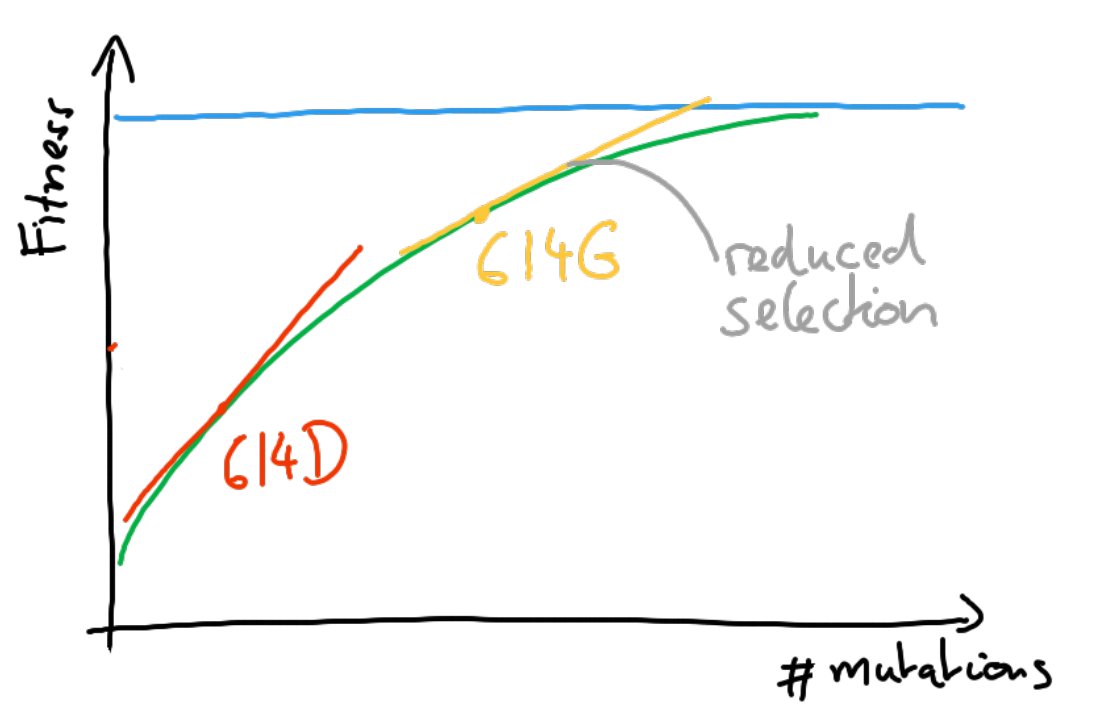

But surely these few early mutations didn't exhaust the supply of beneficial mutations -- we know the virus kept adapting. So why do we see this drop?

6/N

But surely these few early mutations didn't exhaust the supply of beneficial mutations -- we know the virus kept adapting. So why do we see this drop?

6/N

The analyses underlying the results and graphs above are simple descriptive statistics that revealed some clear patterns. But this simplicity hopefully makes interpretation easier.

We will see whether similar patterns hold in the future!

11/N

We will see whether similar patterns hold in the future!

11/N

This work builds on the work of 1000s of scientists that generate SARS-CoV-2 sequence data from millions of patients around the world! Thank you very much!

12/N

12/N

Loading suggestions...