Fleshing out my thoughts on the scariest macroeconomics paper of 2022: "Understanding U.S. Inflation During the COVID Era" by Larry Ball, Daniel Leigh, & Prachi Mishra. This 🧵 expands on the broader points I made in my @WSJopinion. wsj.com

I was a discussant for the paper at the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity earlier today. You can find the paper and my discussion slides here. Here is the outline of my comments.

dropbox.com brookings.edu

dropbox.com brookings.edu

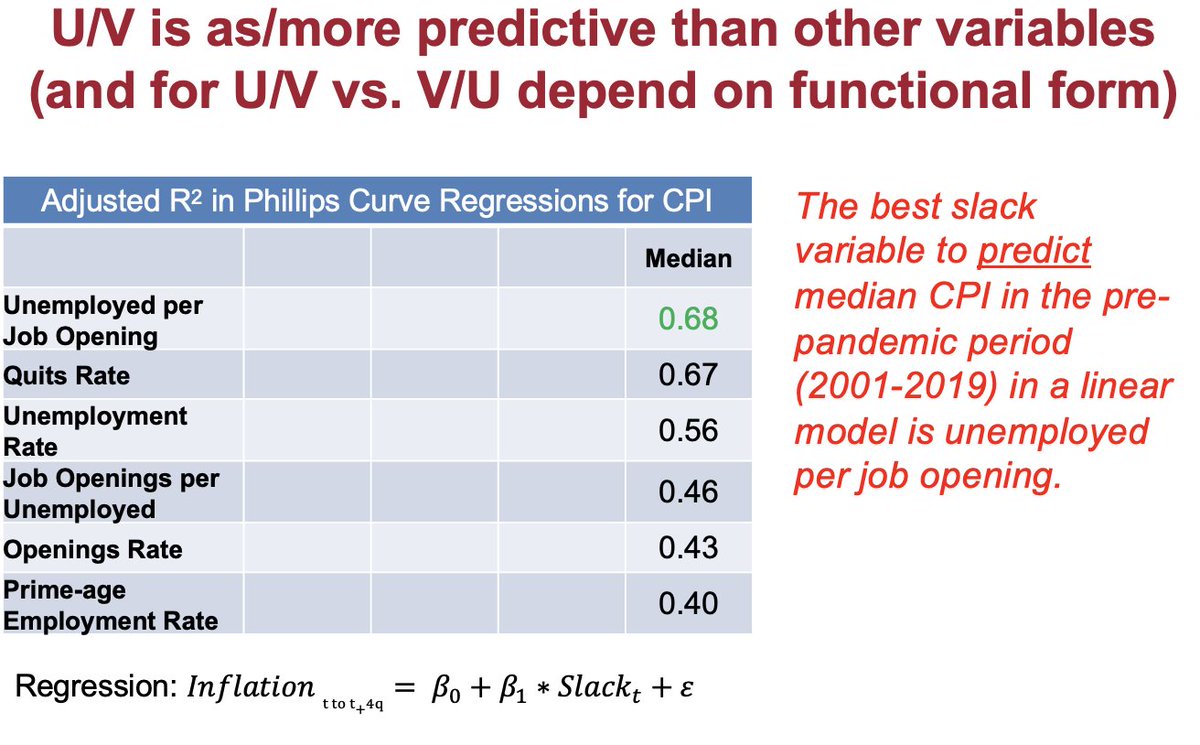

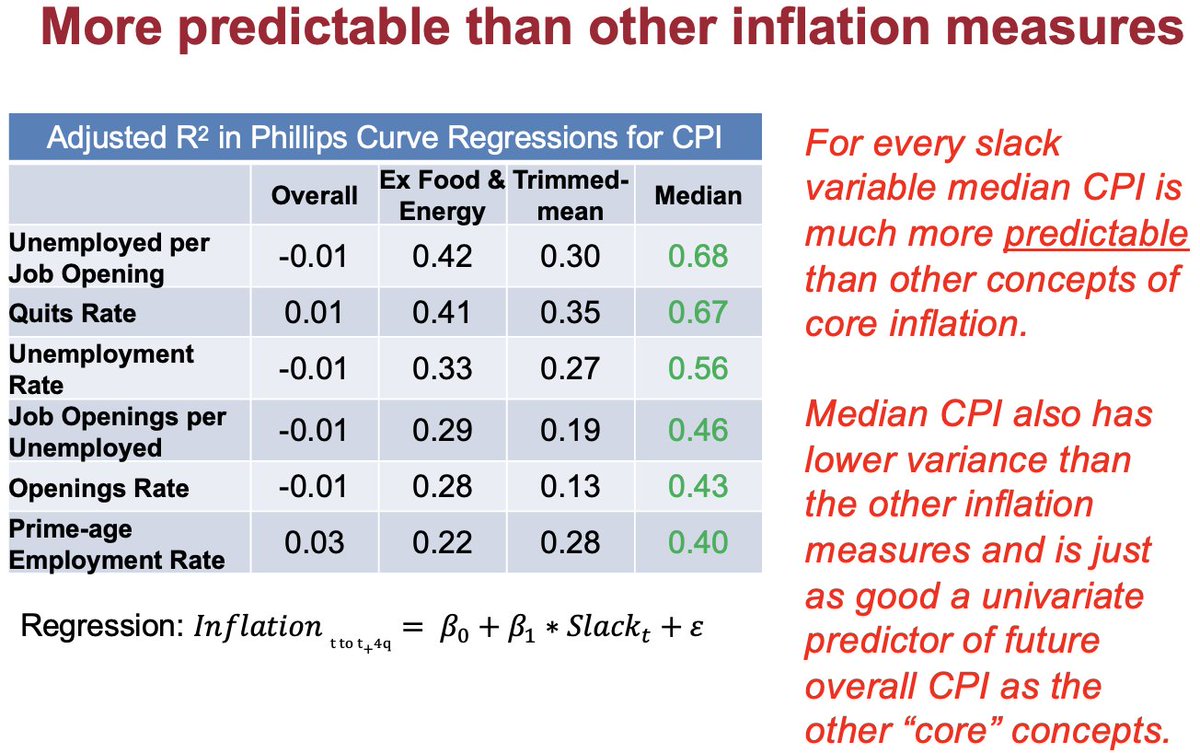

3. MEDIAN CPI IS THE RIGHT INFLATION MEASURE

The authors focus on median CPI (as opposed to the usual mean), which throws out all outliers. I had been semi-skeptical but their results, papers they sent me back to, and...

The authors focus on median CPI (as opposed to the usual mean), which throws out all outliers. I had been semi-skeptical but their results, papers they sent me back to, and...

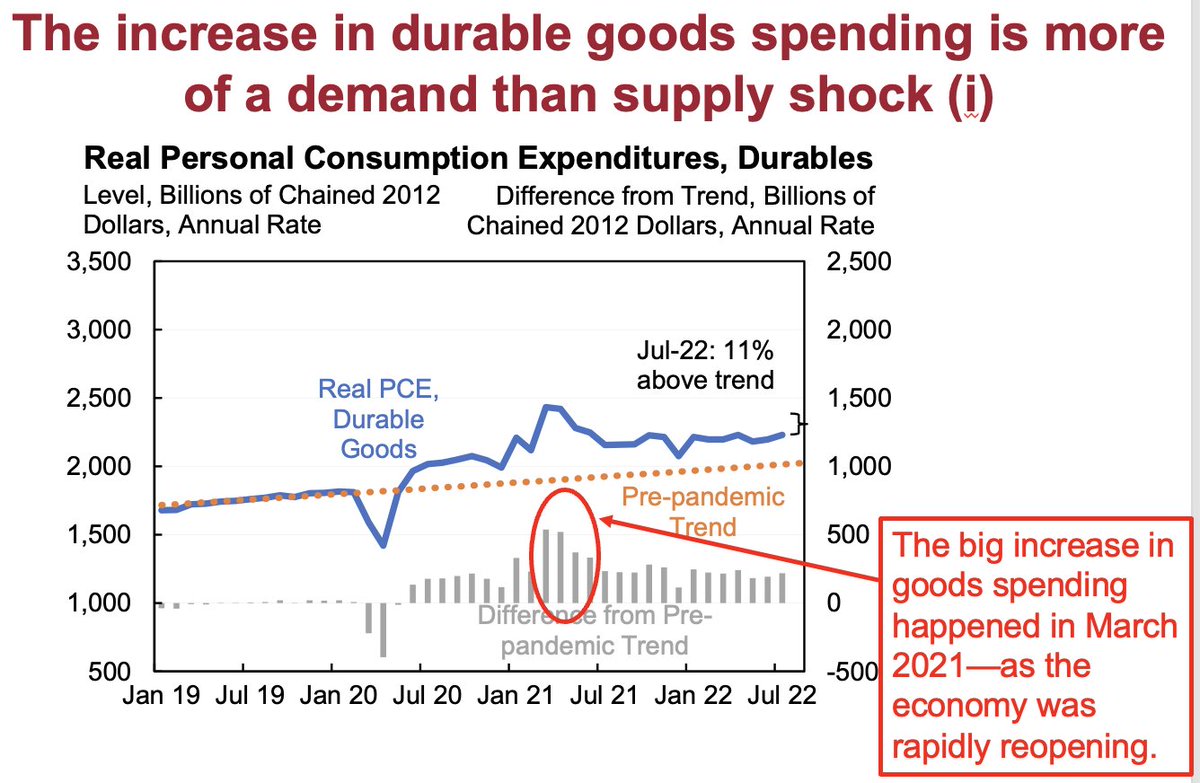

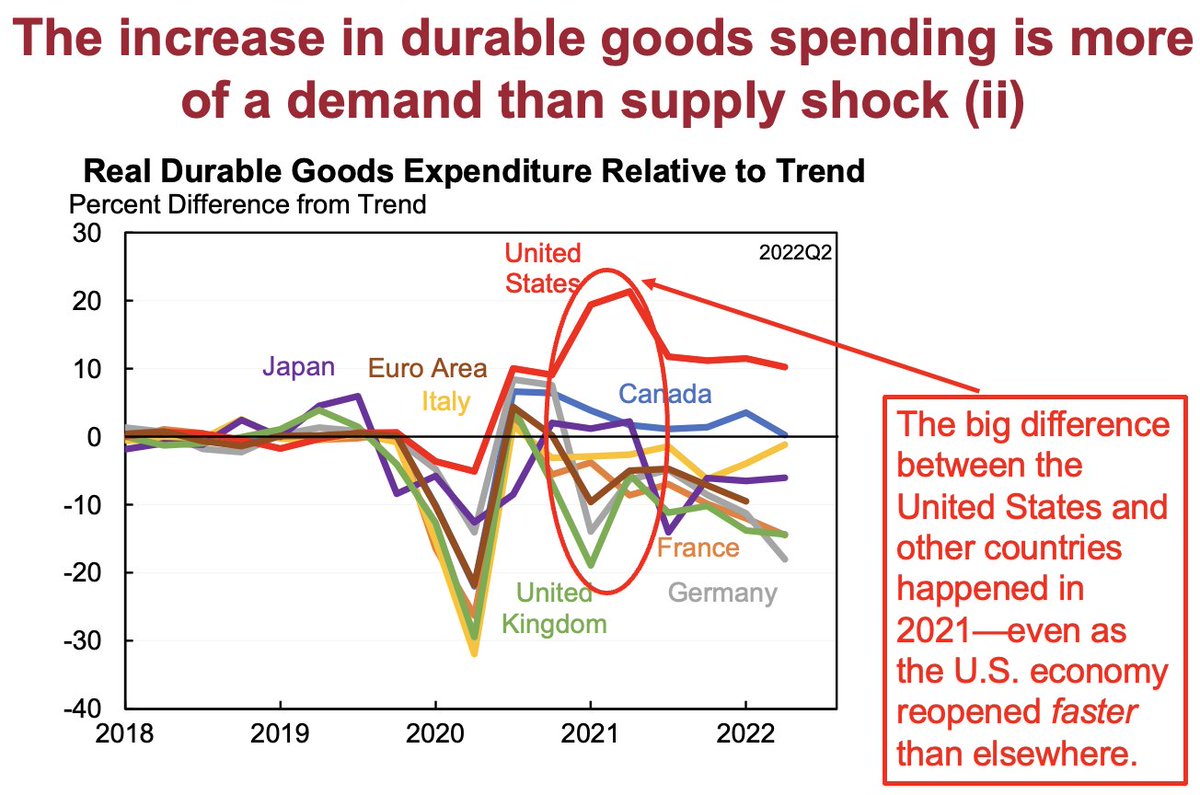

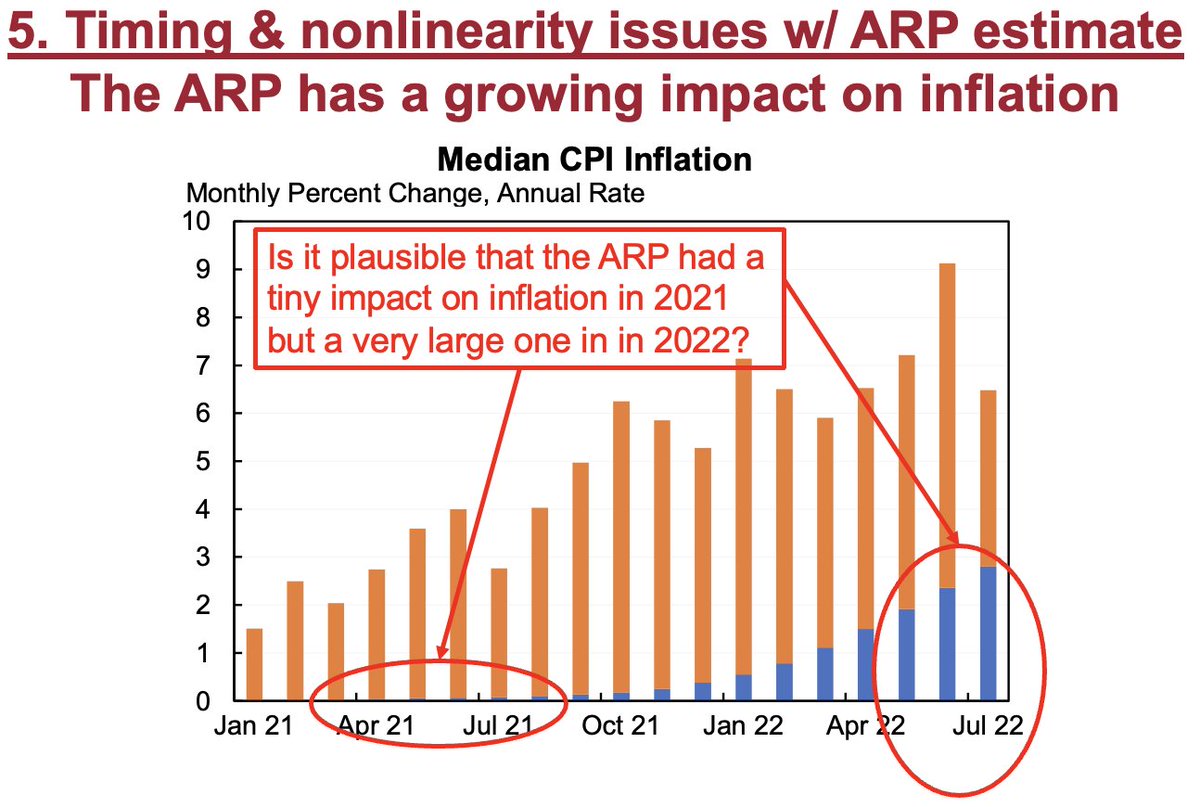

4. HEADLINE SHOCKS REFLECT SUPPLY AND DEMAND

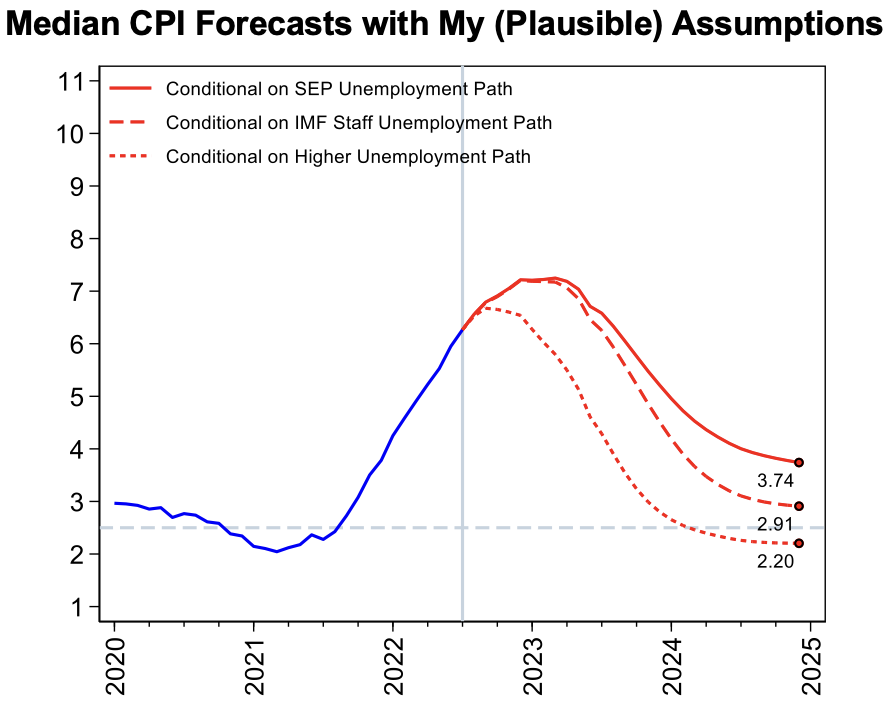

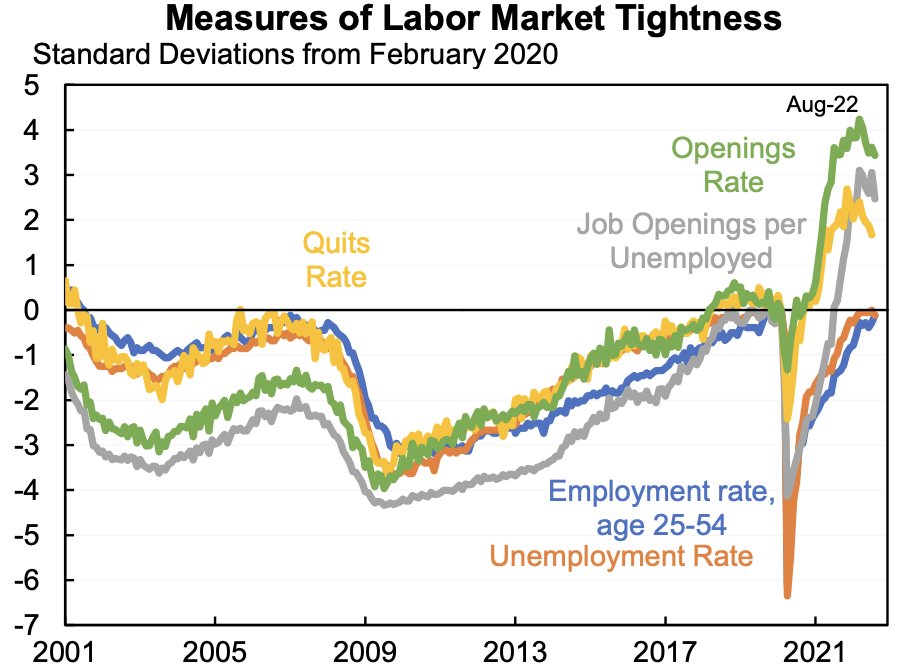

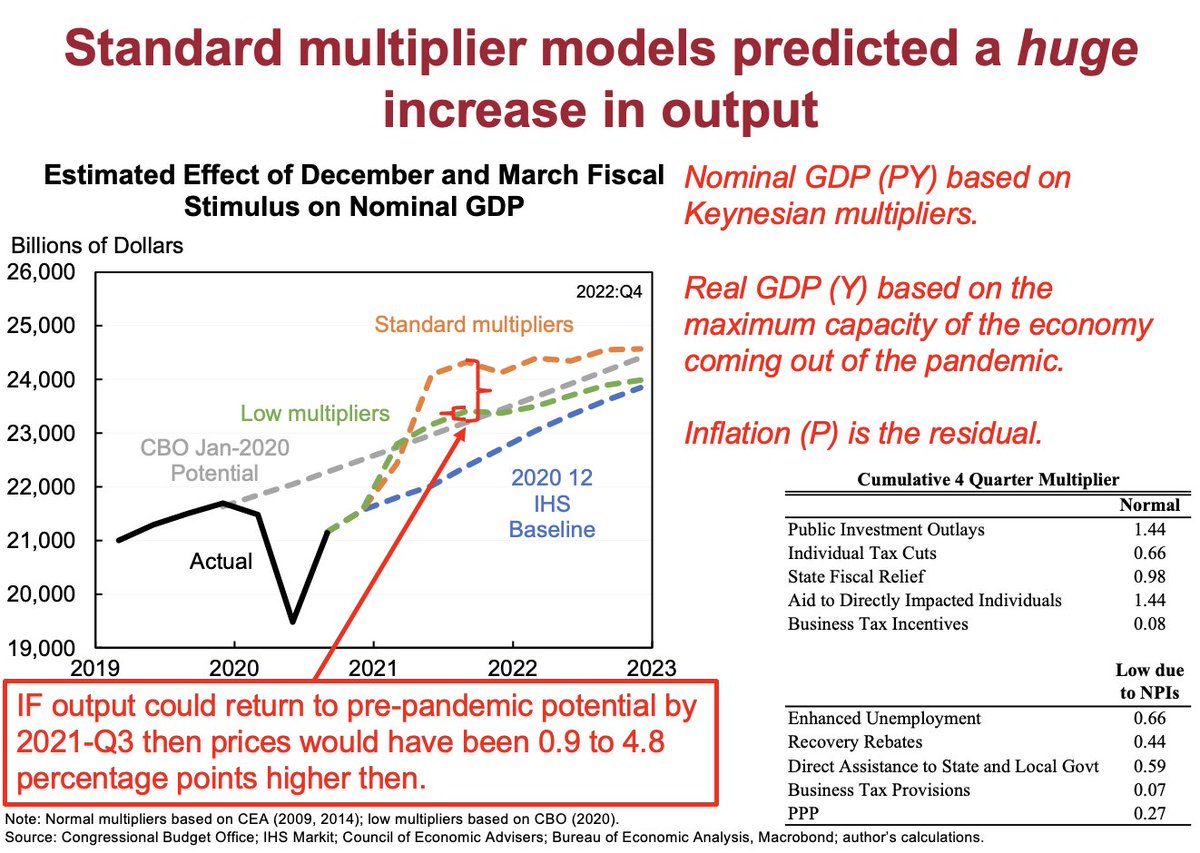

The authors rely a lot on a variable called "headline shocks" which is the difference between mean and median CPI. They find it matters a lot (by definition). Question is how to interpret it: I would argue a lot is demand.

The authors rely a lot on a variable called "headline shocks" which is the difference between mean and median CPI. They find it matters a lot (by definition). Question is how to interpret it: I would argue a lot is demand.

I've written about this a bunch before, see this thread for more. Short version: part of why there have been shortages, supply chain issues, backed up ports, etc., is that people were trying to buy a lot more than before.

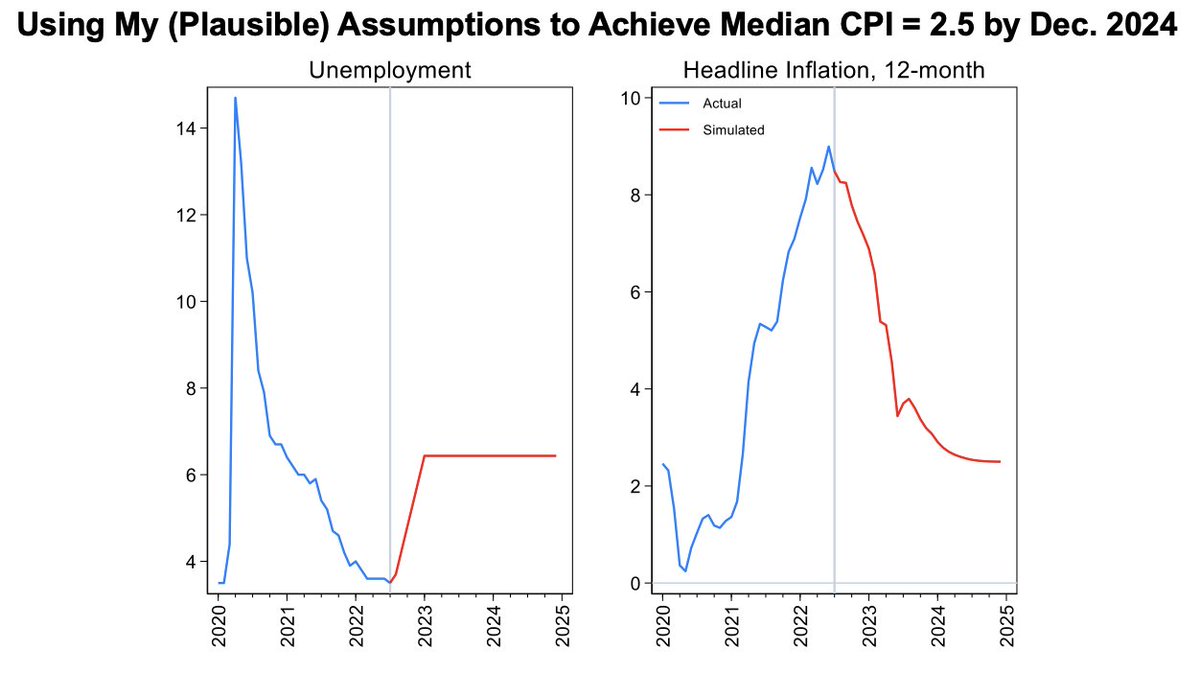

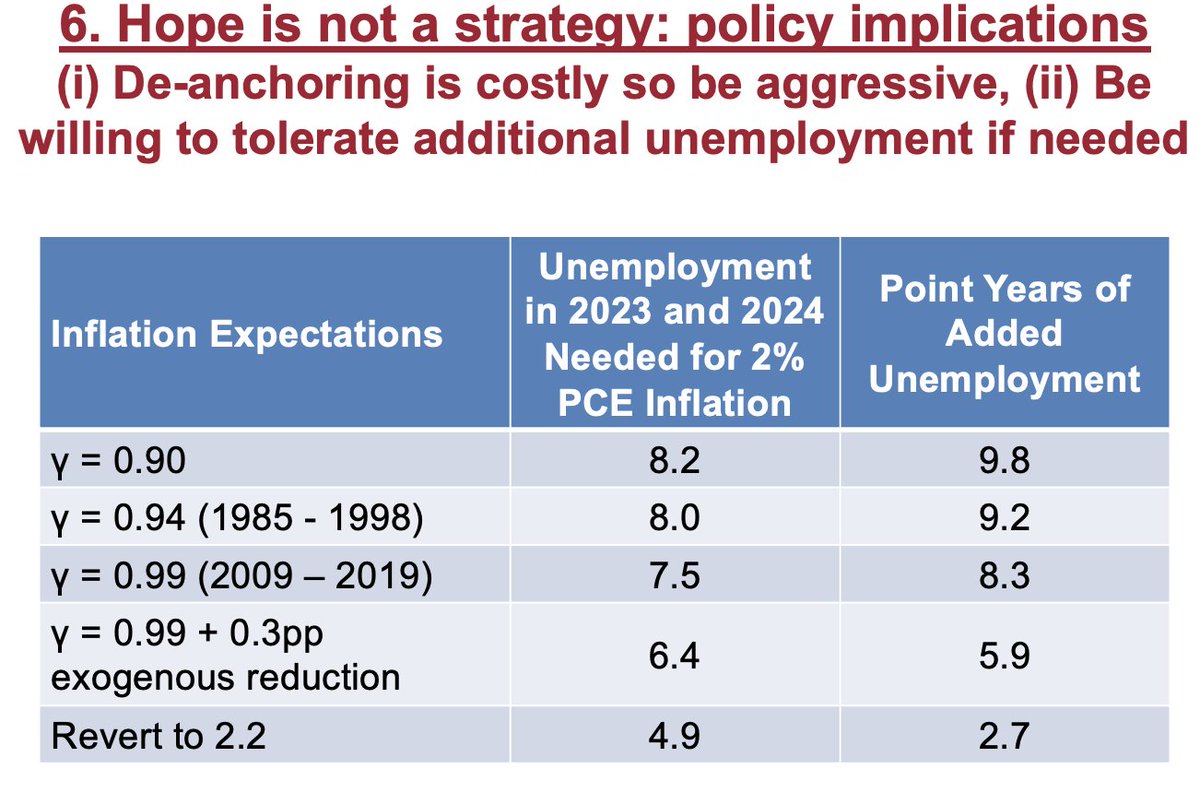

(ii) Be willing to tolerate unemployment. The Fed's goal should not be to raise the unemployment rate (or reduce vacancies), in fact the opposite is a goal. BUT, this suggests they may need to tolerate higher unemployment if they want to bring inflation down.

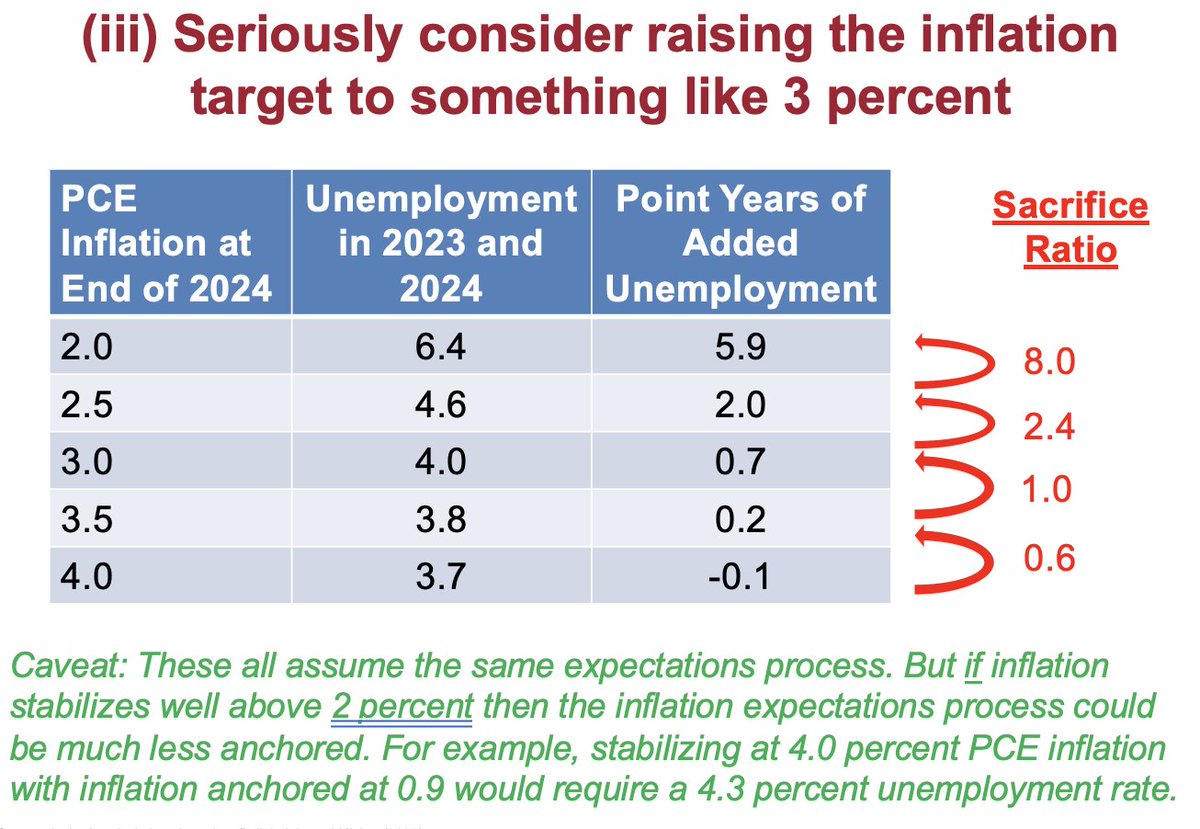

(iii) Seriously consider raising the inflation target to something like 3 percent

This one is tricky. On a blank slate a 3% target would be better than a 2% target. But shifting to that could deanchor expectations.

This one is tricky. On a blank slate a 3% target would be better than a 2% target. But shifting to that could deanchor expectations.

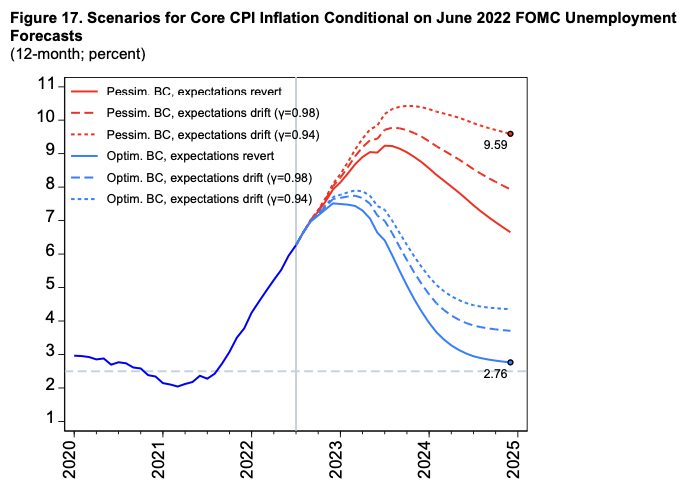

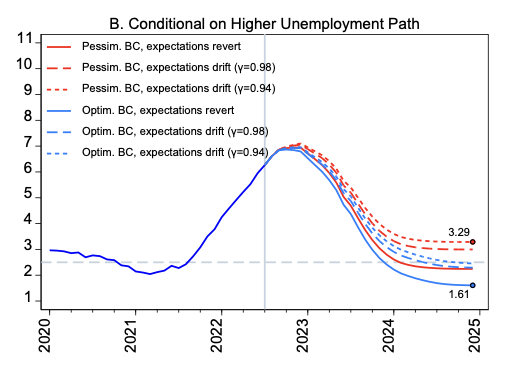

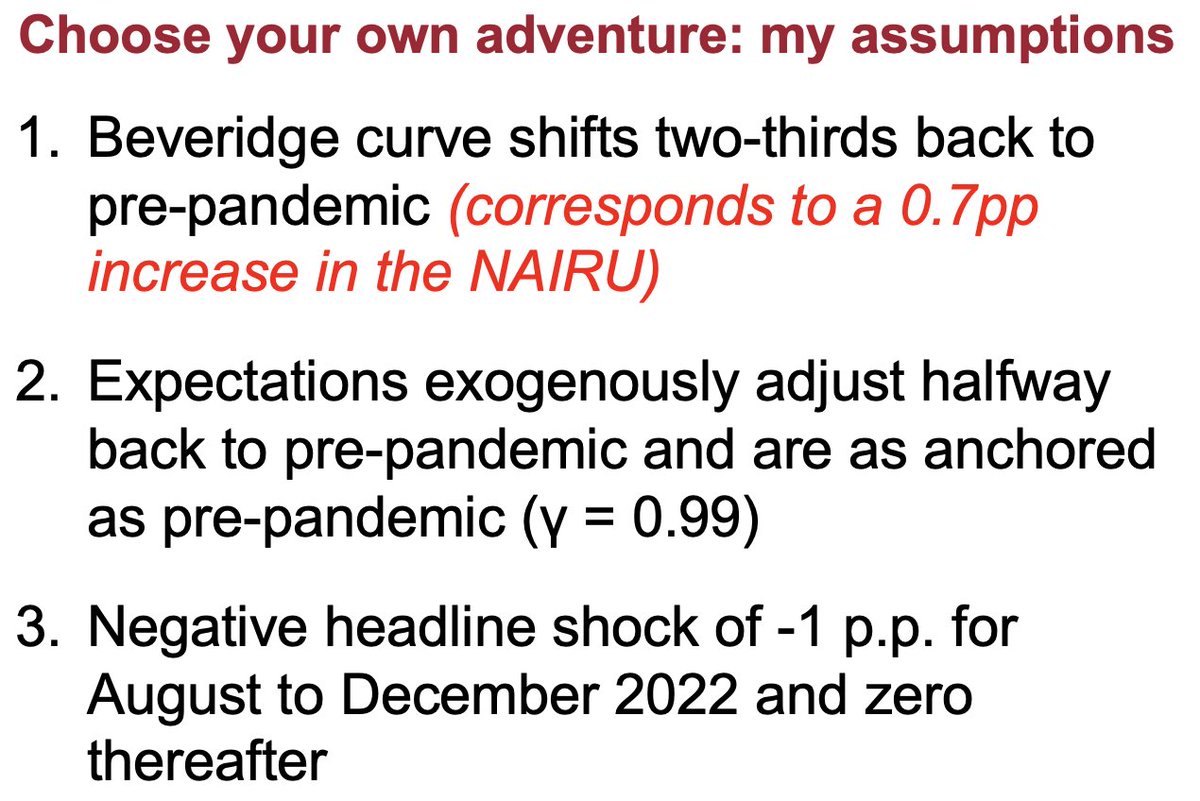

In sum, policy shouldn't be based on how we hope the economy functions but how it does function. There is a *huge* amount of uncertainty. Maybe it will work out. Maybe it will be much scarier than what I had above (as some BPEA participants argued).

Here are links again to my @WSJopinion (with my interpretation / running of their model), the Ball-Leigh-Mishra paper, and my full slides. wsj.com brookings.edu dropbox.com

Loading suggestions...