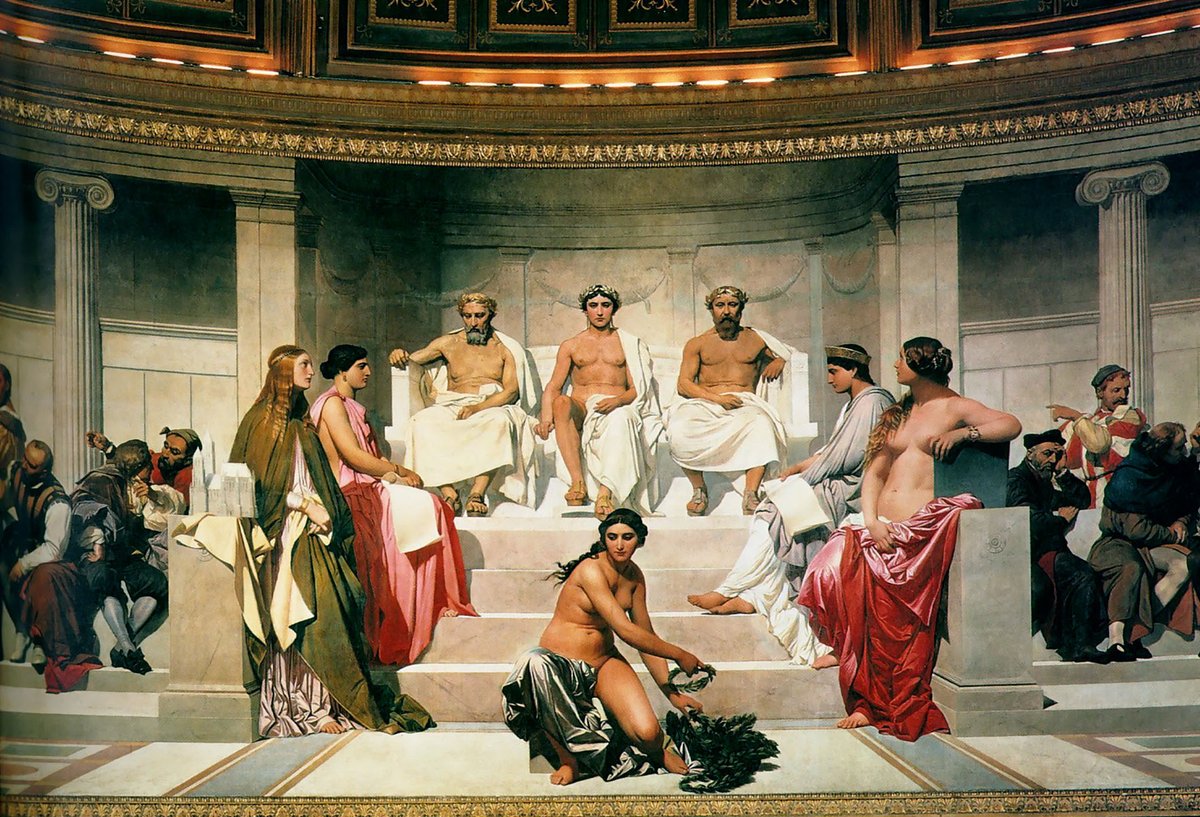

The Académie des Beaux-Arts was a French fine arts school which not only taught young artists but also set the aesthetic standards and methods of the age.

And they prioritised a very particular type of painting based on the ideas of the Renaissance...

And they prioritised a very particular type of painting based on the ideas of the Renaissance...

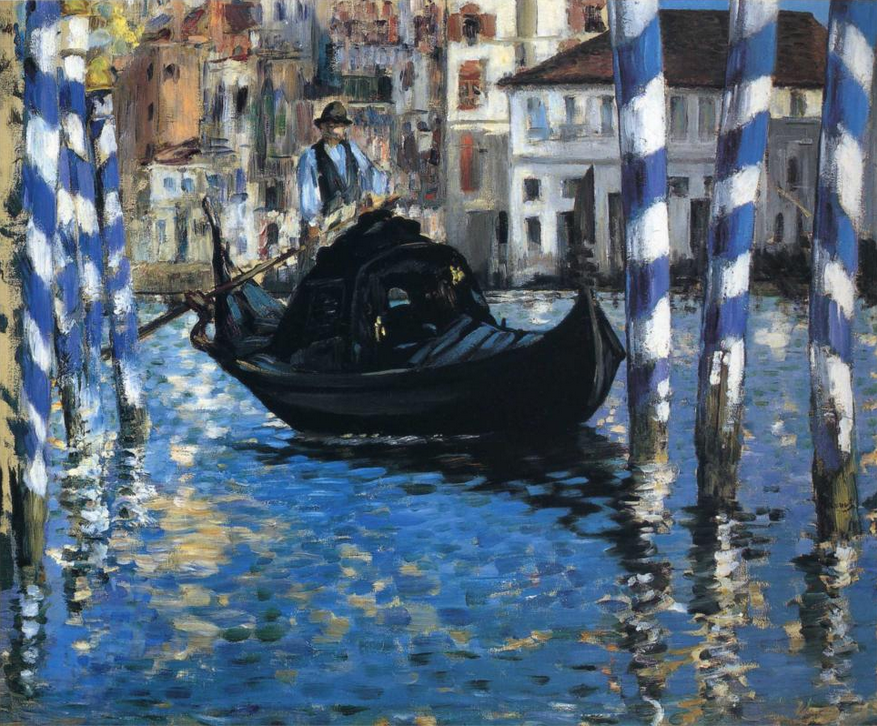

This reaction against Academicism was taken up by a group of young artists in the 1860s, who all met while learning the Academic style.

They were Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frederic Bazille; and their leader was the slightly older Edouard Manet...

They were Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frederic Bazille; and their leader was the slightly older Edouard Manet...

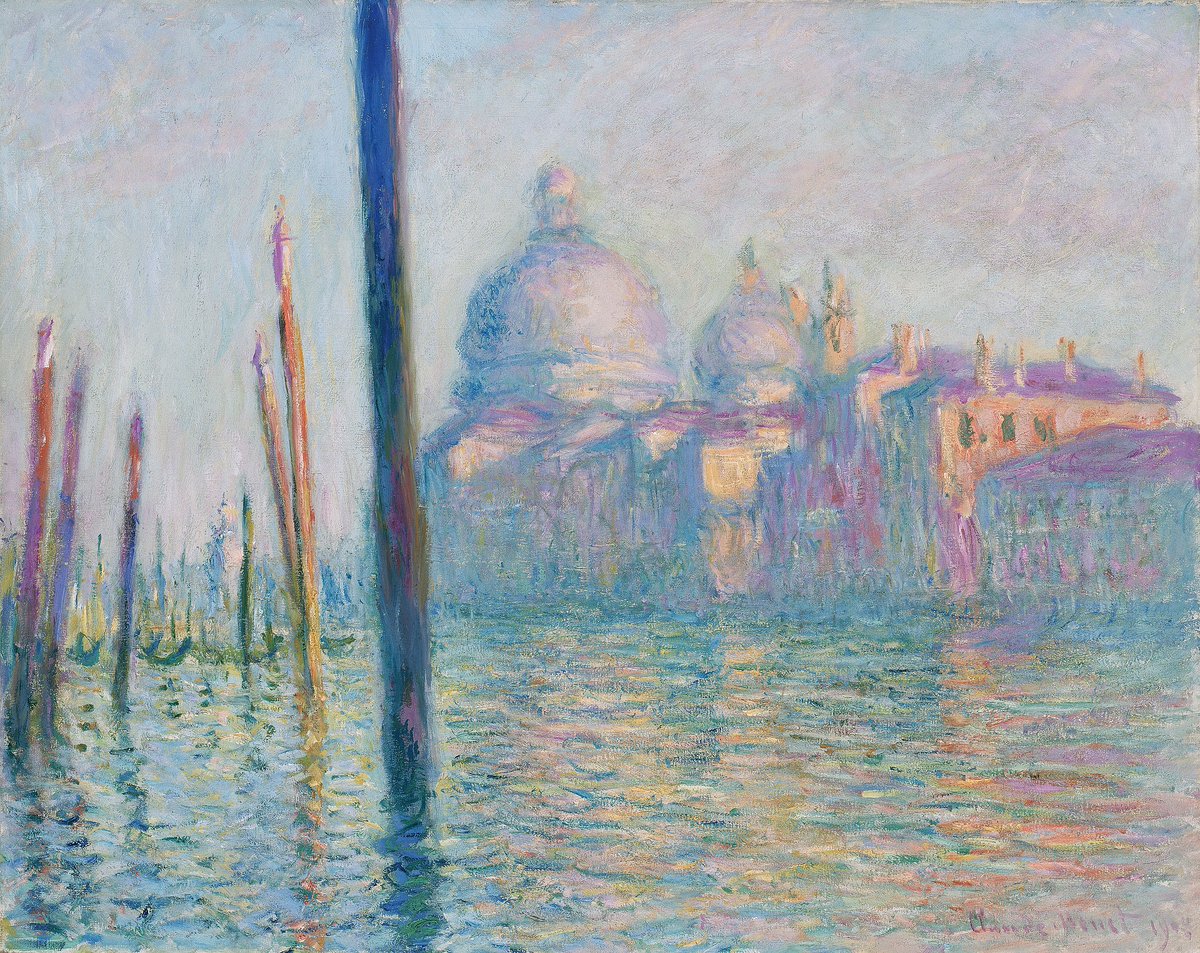

In this way, Monet and his contemporaries weren't quite revolutionaries.

Rather, their preference for colour over drawing was directly inspired by a similar divergence in 16th century Italy, during the Renaissance.

Rather, their preference for colour over drawing was directly inspired by a similar divergence in 16th century Italy, during the Renaissance.

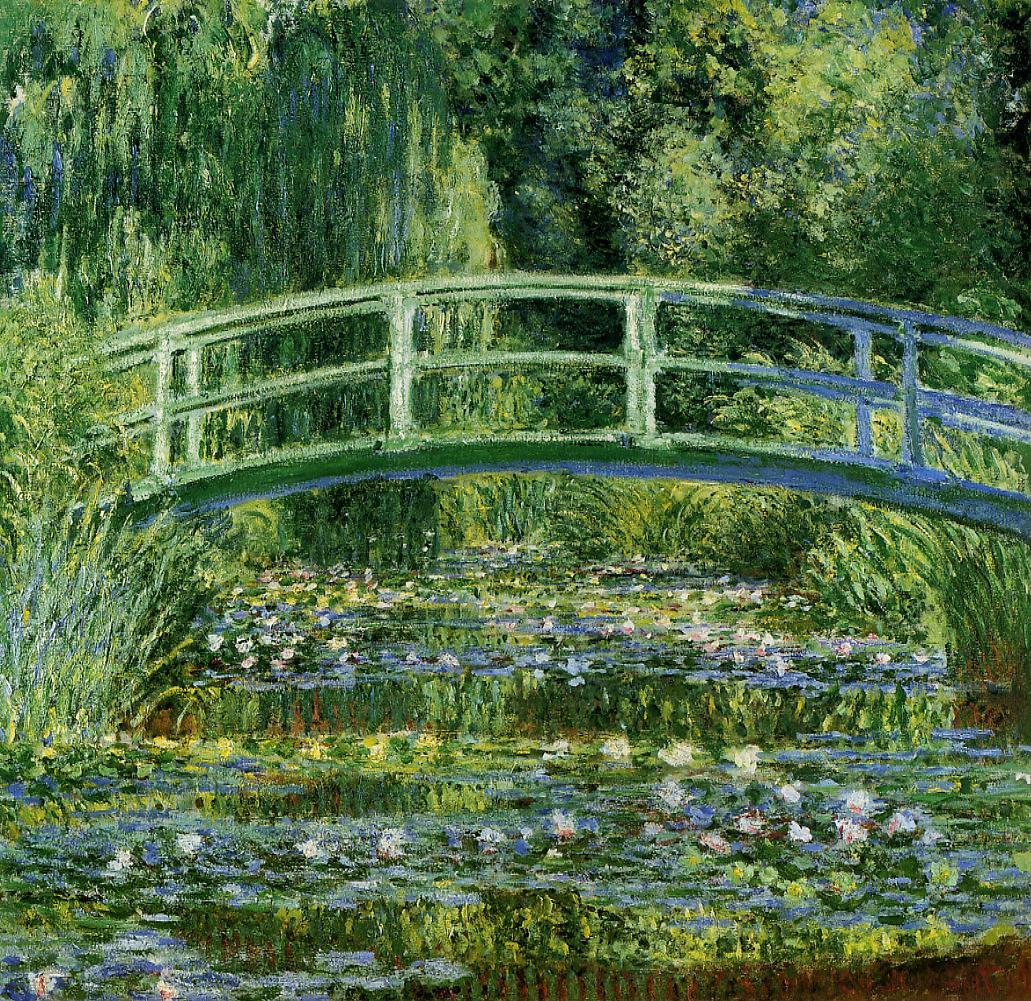

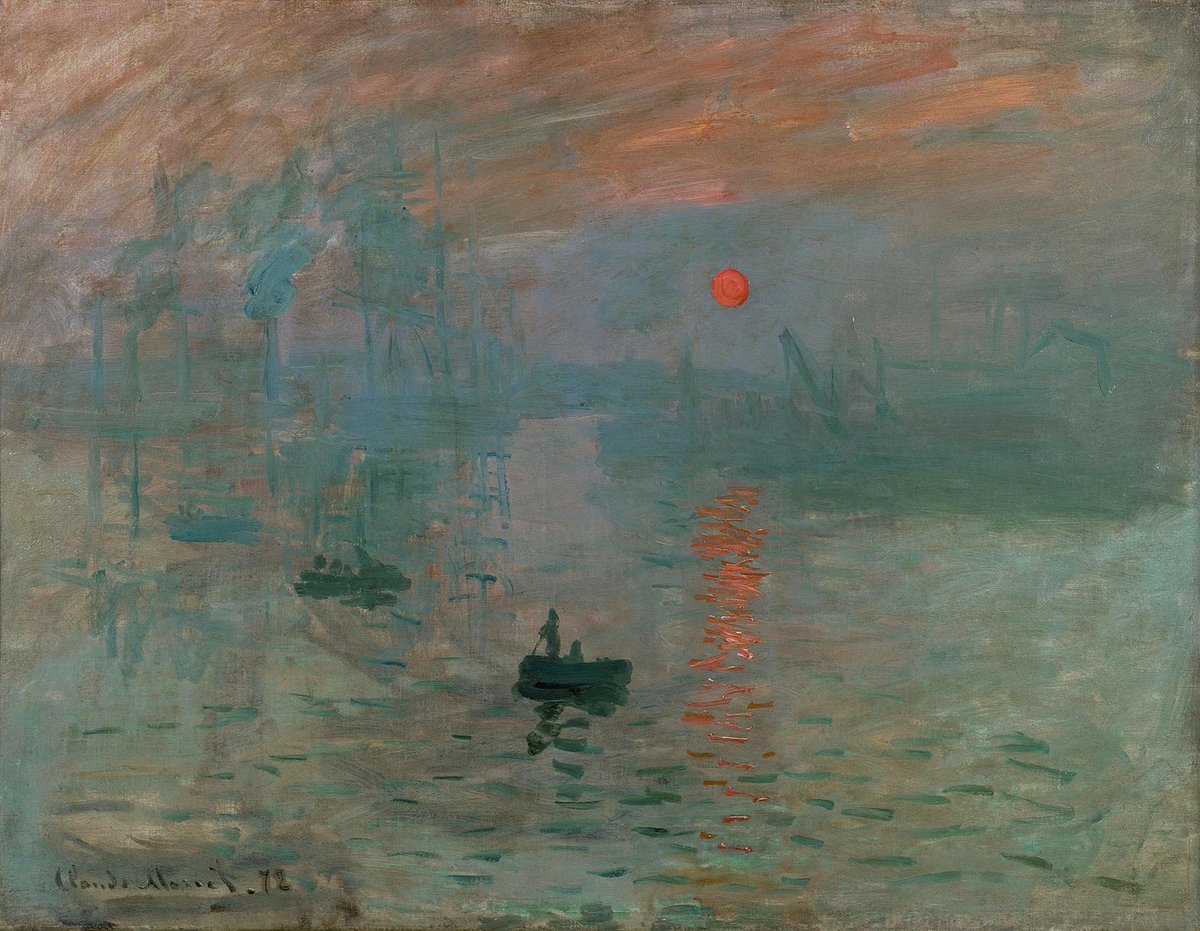

Monet and his gang took on this term as a badge of honour, despite the mockery and criticism of the artistic establishment.

Little could Leroy have known that, within a few decades, these silly Impressionists would have far eclipsed the Academy in popularity and influence...

Little could Leroy have known that, within a few decades, these silly Impressionists would have far eclipsed the Academy in popularity and influence...

Impressionism in the strictest sense soon evolved and splintered into several different artistic movements.

It had broken the monopoly of the Academy and thrown open the doors of possibility. Art was no longer shackled... it could be anything.

It had broken the monopoly of the Academy and thrown open the doors of possibility. Art was no longer shackled... it could be anything.

And that, with many details elided, is a brief introduction to Impressionism.

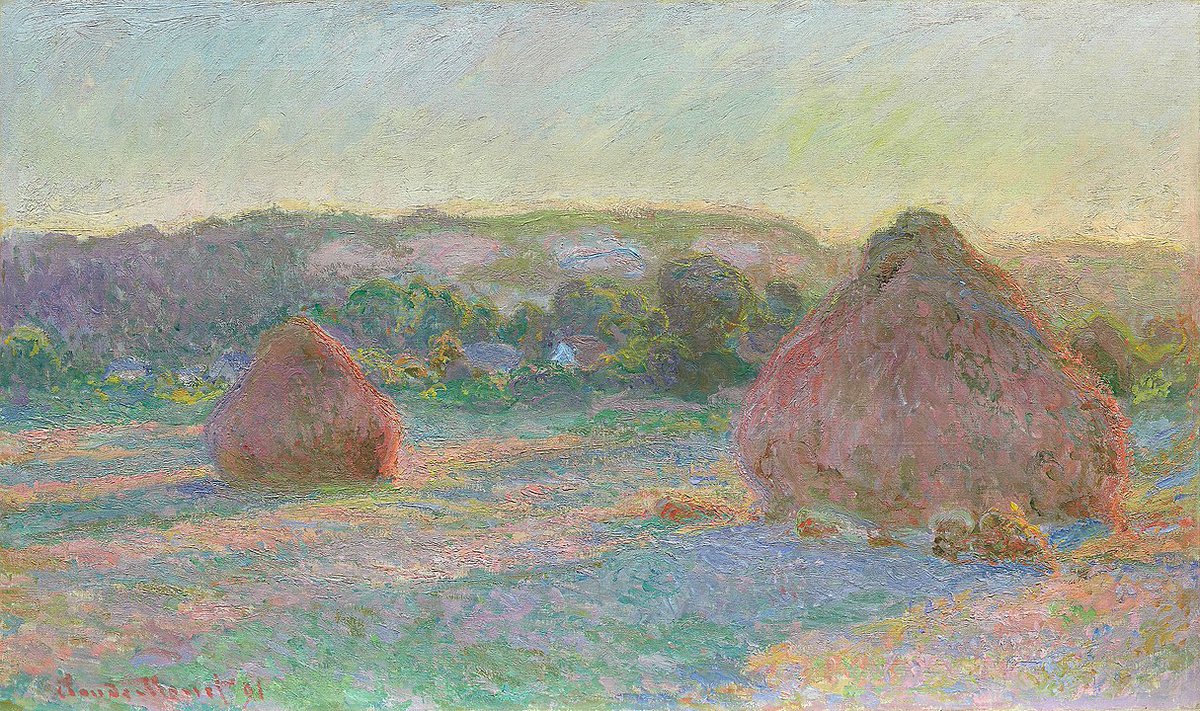

Many of the most enduringly popular painters are from this relatively short artistic era, and their initial rejection by the establishment has set the standard for artistic rebellion ever since.

Many of the most enduringly popular painters are from this relatively short artistic era, and their initial rejection by the establishment has set the standard for artistic rebellion ever since.

Loading suggestions...