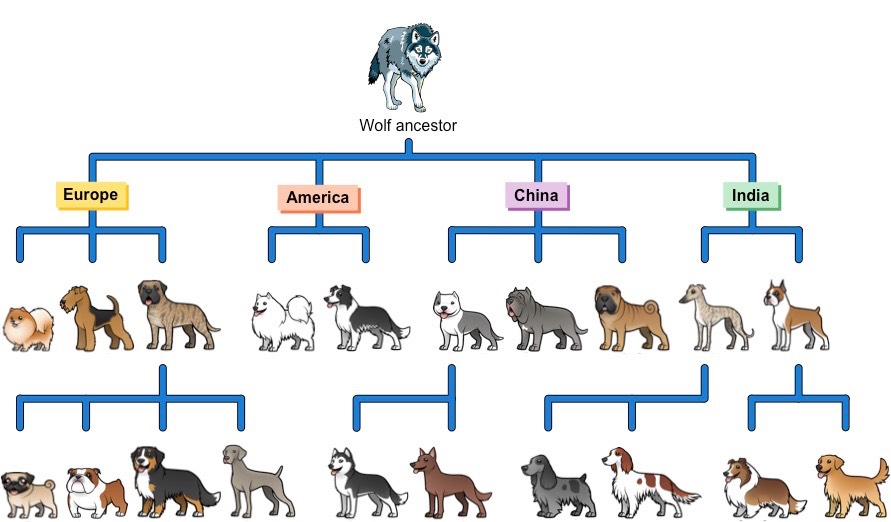

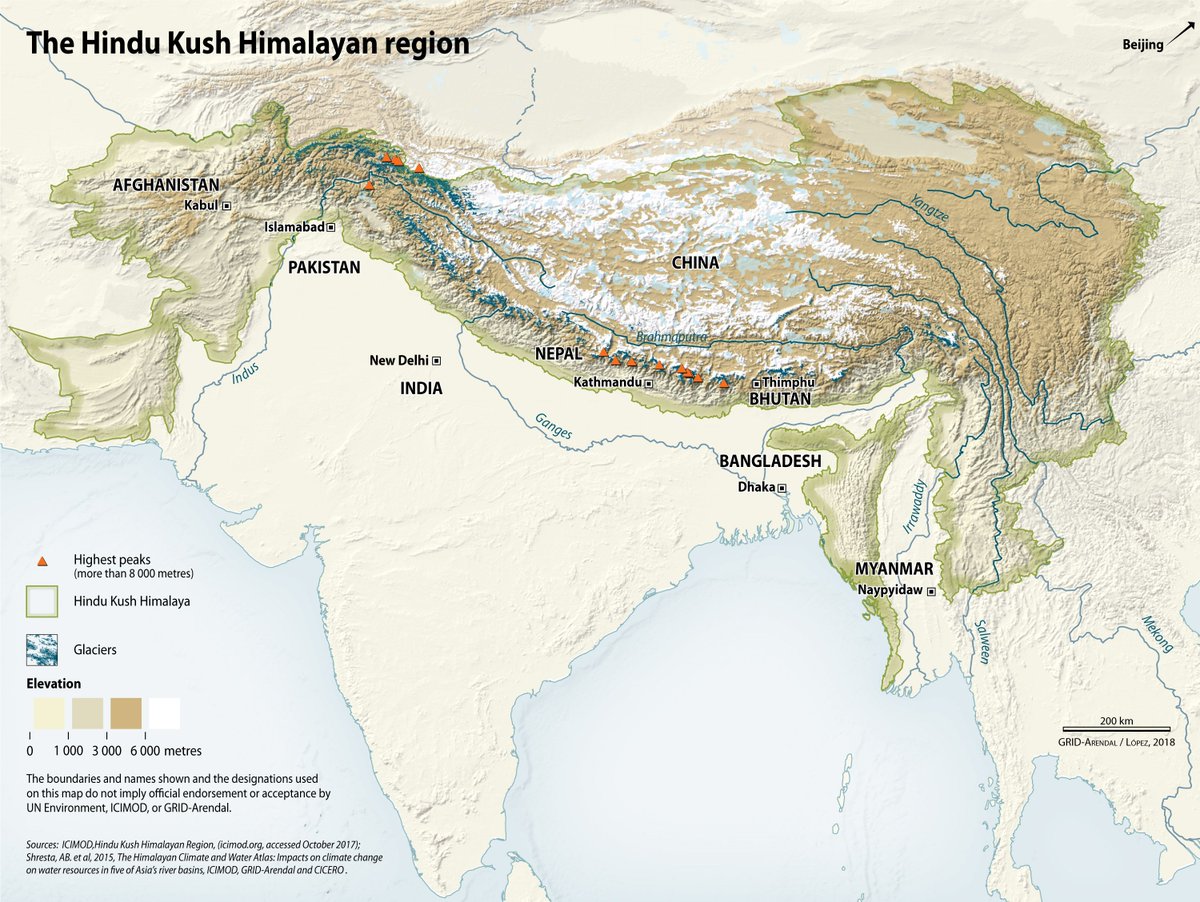

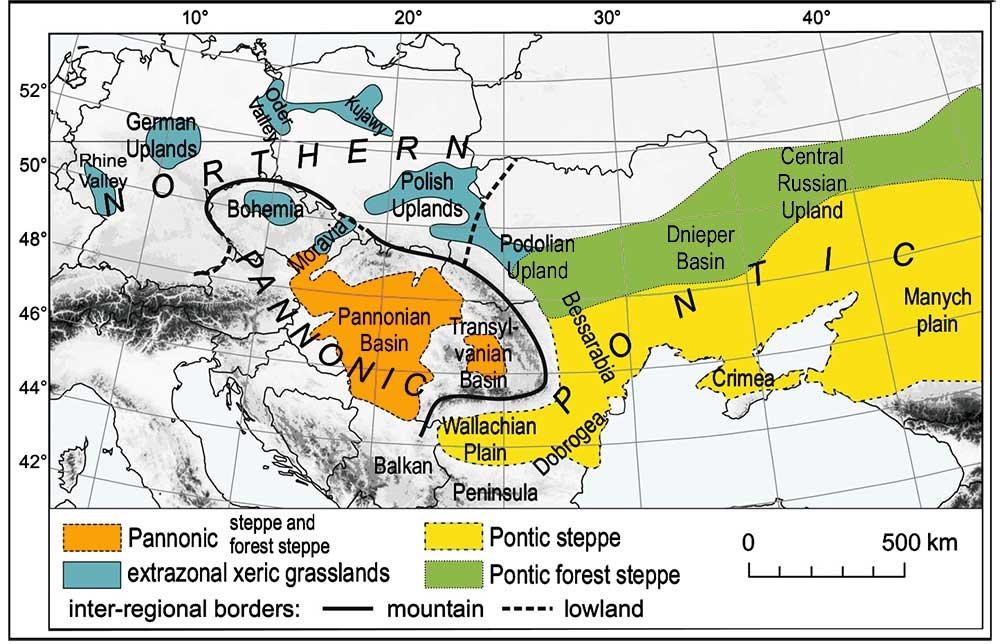

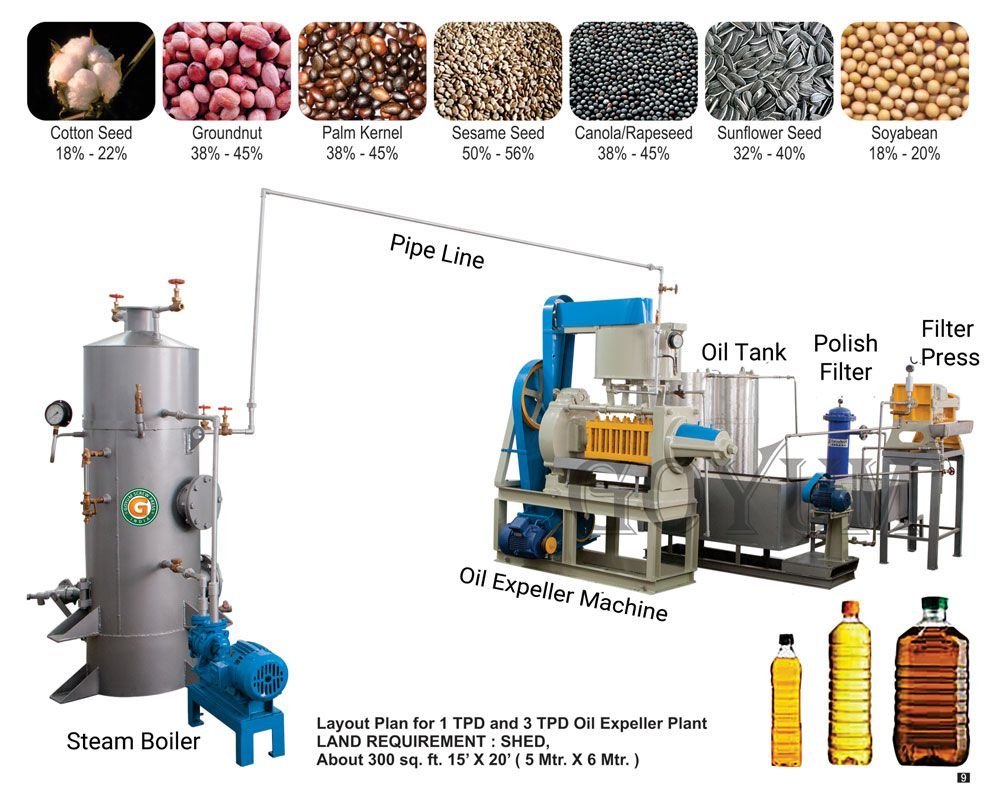

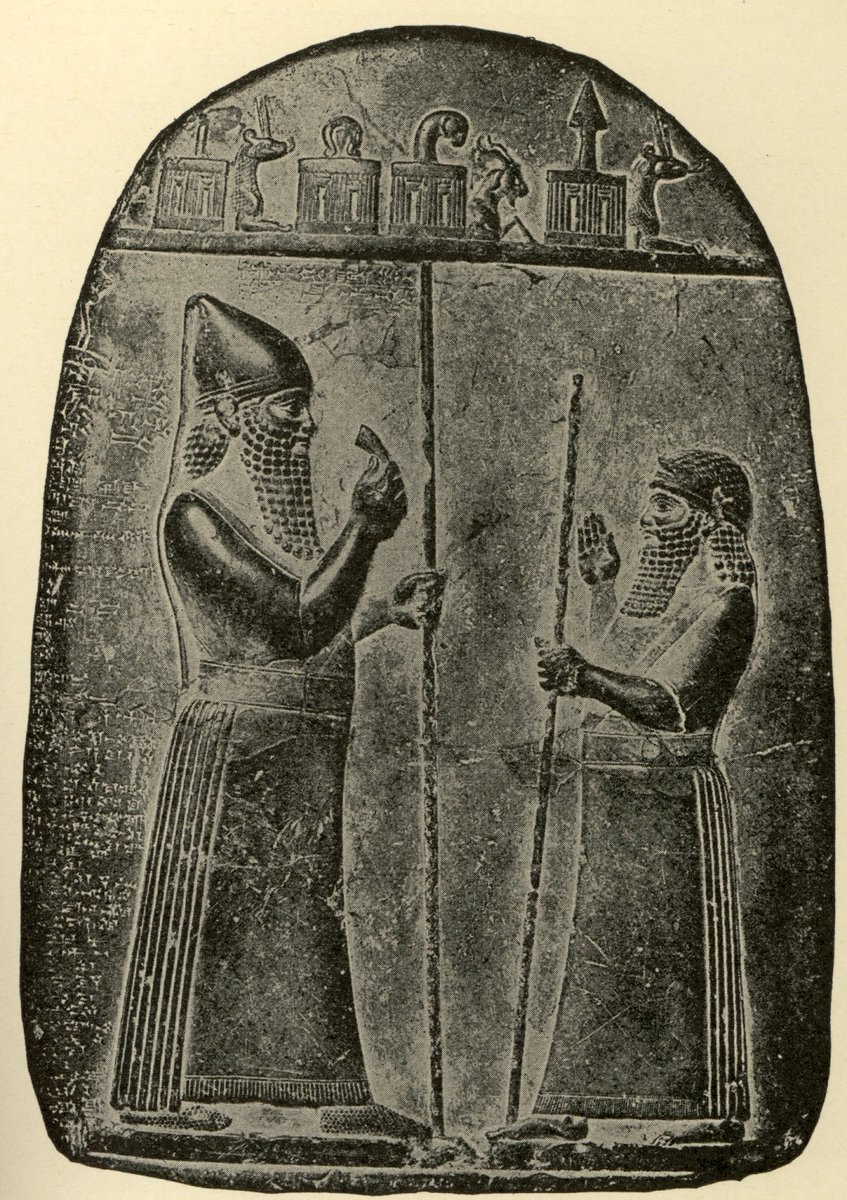

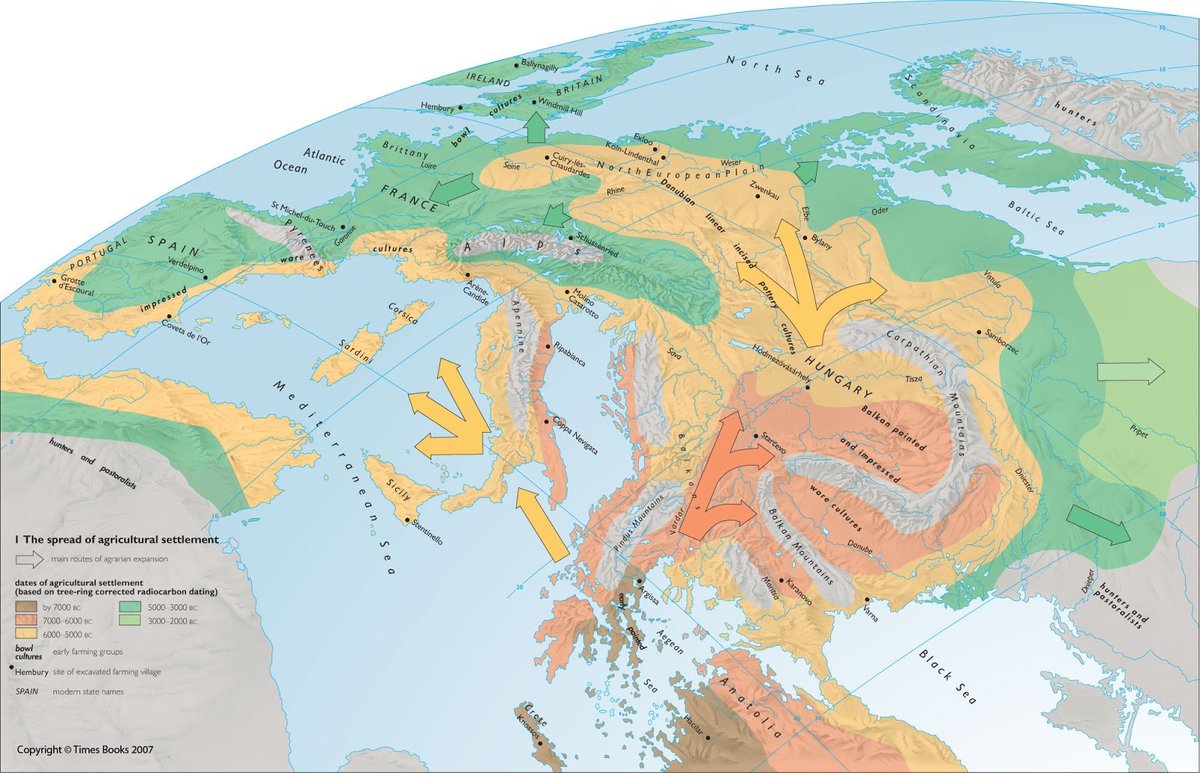

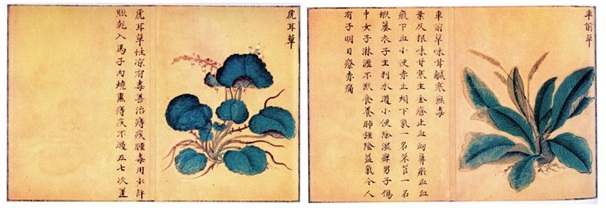

The theory is that they spread along commercial land routes that existed even then between India & China and Europe, with central Asia as the crossroads. Even as far back as the Indus valley civilization, such trade took place with Mesopotamia

*Exportation to Korea not China, oops

Loading suggestions...