(2/17) Warning: there will be math, but (as long as you made it through high school algebra) you can handle it.

Actually... I wonder what percentage of my audience is still in high school...

See the disclaimer below.

Actually... I wonder what percentage of my audience is still in high school...

See the disclaimer below.

(3/17) Let's say you have a large amount of data that, for whatever reason, is private.

How can you provide a public audience assurance that you will not alter the data without allowing them to see it?

How can you provide a public audience assurance that you will not alter the data without allowing them to see it?

(4/17) The naïve option just doesn't work; we cannot just reveal all the data and allow people to publicly verify that no changes are happening.

We need to find a way to provide a unique fingerprint of that specific set of data to act as a signature.

We need to find a way to provide a unique fingerprint of that specific set of data to act as a signature.

(5/17) Hash functions are a great candidate for this kind of job: a hash function irreversibly transforms an arbitrary amount of data into a unique string of uniform length. Even a single-digit change will result in an entirely new hash.

So, maybe a hash-based solution?

So, maybe a hash-based solution?

(6/17) The problem with hash functions is that the process of creating a function's unique fingerprint necessarily destroys all other information.

Once generated, a hash acts as a unique identifier, a pseudo-random string of data, and not much more.

Once generated, a hash acts as a unique identifier, a pseudo-random string of data, and not much more.

(7/17) While hashes are useful, they destroy too much useful information for many applications. For example, you cannot verify if a particular piece of data was in the data set using a hash; it's all or nothing.

So, we must look for alternative schemes.

So, we must look for alternative schemes.

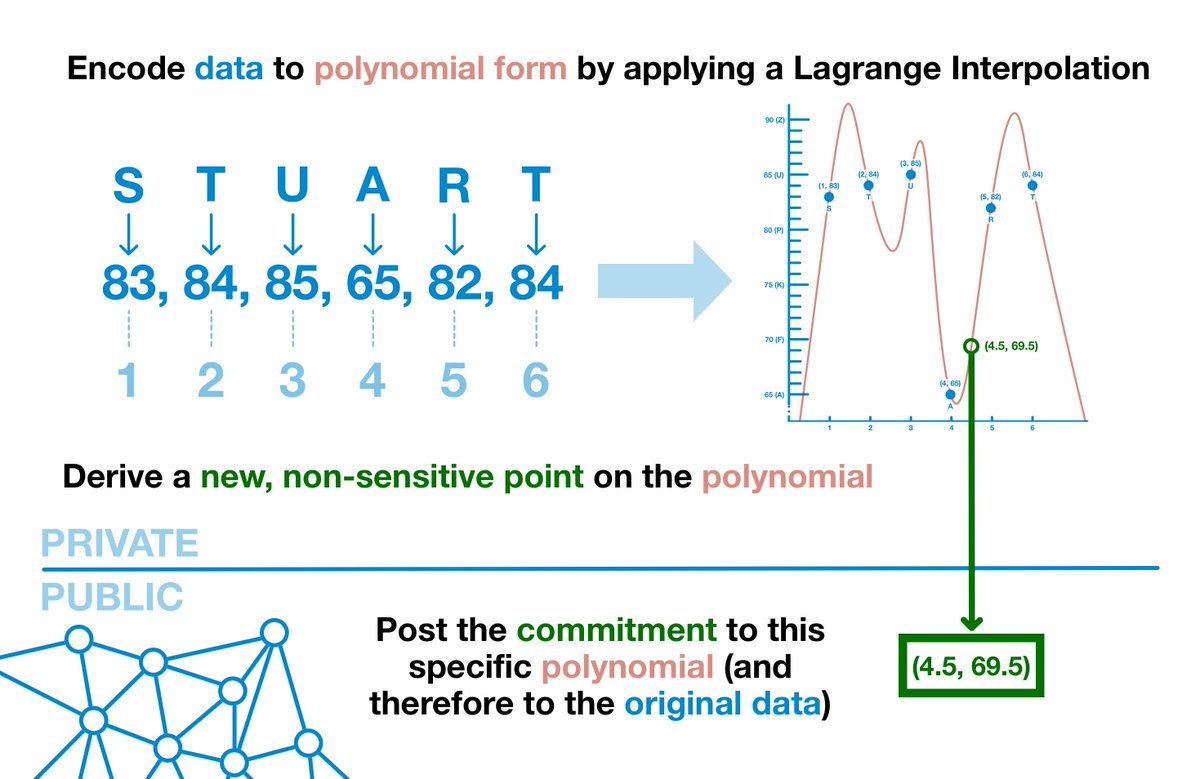

(8/17) Before we continue, we need to quickly review polynomial encoding.

Tl;dr you can represent any arbitrary data set as a polynomial using a special mathematical function called a Lagrange Interpolation.

Data → polynomial → data

Data = polynomial

Tl;dr you can represent any arbitrary data set as a polynomial using a special mathematical function called a Lagrange Interpolation.

Data → polynomial → data

Data = polynomial

(9/17) Let's transform our database into a polynomial, which we will refer to as f(x).

Now, we can't post f(x); that would be equivalent of posting the data.

But what if we posted a point of data on data on that polynomial; one that didn't provide a real value?

Now, we can't post f(x); that would be equivalent of posting the data.

But what if we posted a point of data on data on that polynomial; one that didn't provide a real value?

(11/17) So here's the idea: transform our data into a polynomial and provide the public with an evaluation value for a non-sensitive part of the curve.

Remember, the curve defined by the polynomial is infinite and your data is not; there are plenty of non-sensitive points.

Remember, the curve defined by the polynomial is infinite and your data is not; there are plenty of non-sensitive points.

(12/17) First and foremost, this point provides assurances that the data has not changed.

Just like a hash function, even a tiny change to the underlying data will have massive consequences for the resulting polynomial.

Just like a hash function, even a tiny change to the underlying data will have massive consequences for the resulting polynomial.

(13/17) New data = new polynomial = new line. If the data changes so will the line, and the non-sensitive point we provided will no longer be valid.

As long as the point we post remains on the polynomial line, the public can be confident that we are working with the same data.

As long as the point we post remains on the polynomial line, the public can be confident that we are working with the same data.

(15/17) "But Haym," you might be asking, "we had hashing this whole time. Why do we need this much more complicated fingerprint scheme?"

Well, dear reader, I have good news and I have bad news.

Well, dear reader, I have good news and I have bad news.

(16/17) The good news is that polynomial commitments are much more sophisticated than hashes, providing huge benefits and some near-magic capabilities.

Yes, the theory is hard to grasp and the computation of polynomial commitments is much more complicated than hashes...

Yes, the theory is hard to grasp and the computation of polynomial commitments is much more complicated than hashes...

(17/17) ...but, I promise you, it is well worth it. You are about to see magic.

Which brings me to the bad news: the magic will have to wait for next time!

Which brings me to the bad news: the magic will have to wait for next time!

Like what you read? Help me spread the word by retweeting the thread (linked below).

Follow me for more explainers and as much alpha as I can possibly serve.

Follow me for more explainers and as much alpha as I can possibly serve.

Loading suggestions...