(2/22) We're in the home stretch! This is the last piece we need to understand KZG commitments.

I am assuming that you've read the threads before this one. If you missed them, no worries I've linked them below.

I am assuming that you've read the threads before this one. If you missed them, no worries I've linked them below.

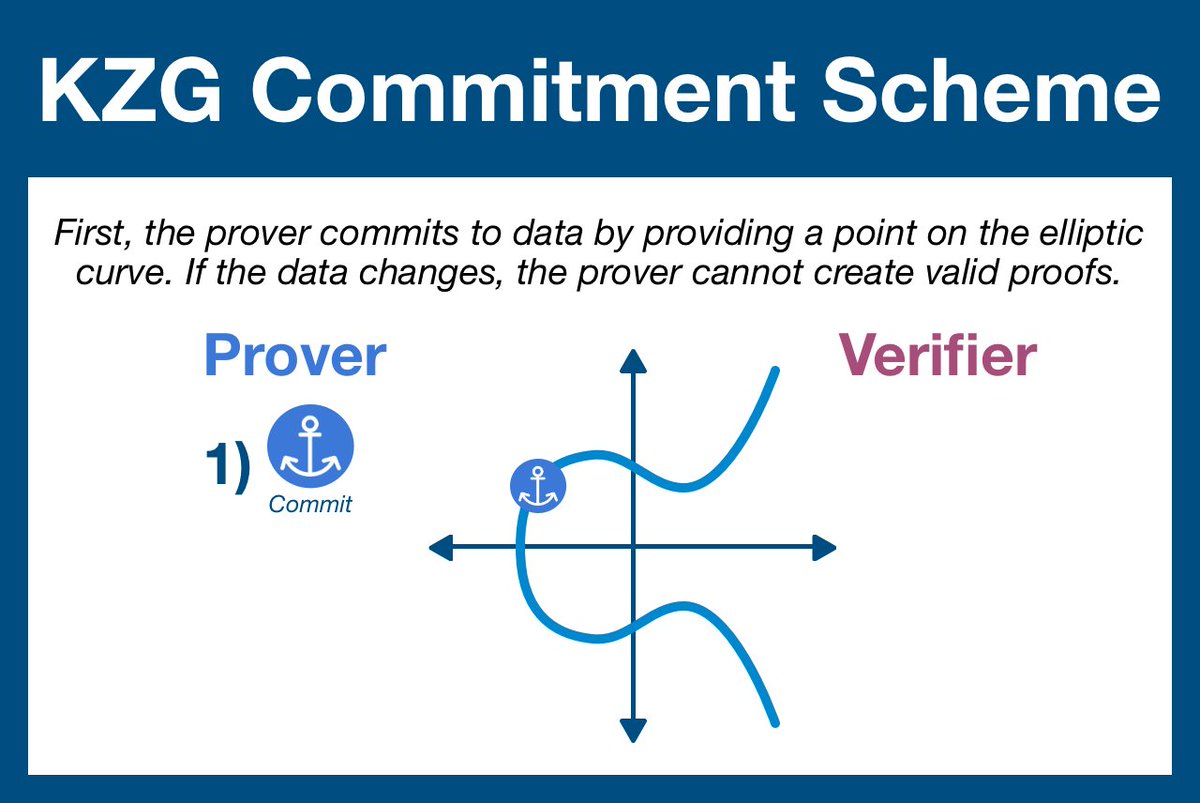

(3/22) A polynomial commitment scheme allows one party to publicly commit to a specific dataset without giving away any info about the underlying data.

Once a commitment has been calculated, the data is locked in; any changes to the data will result in invalid proof generation.

Once a commitment has been calculated, the data is locked in; any changes to the data will result in invalid proof generation.

(4/22) KZG commitments use the magic of elliptical curve cryptography to create something special: a commitment that can be checked at ANY position without revealing any other information.

The prover commits, then the verifier can request a proof around any data point.

The prover commits, then the verifier can request a proof around any data point.

(5/22) The scheme has two types of preparation: hiding a secret number S in an elliptic curve (creating a SRS) and building a Lagrange polynomial from the data.

Using these two pieces, the prover generates a commitment.

Using these two pieces, the prover generates a commitment.

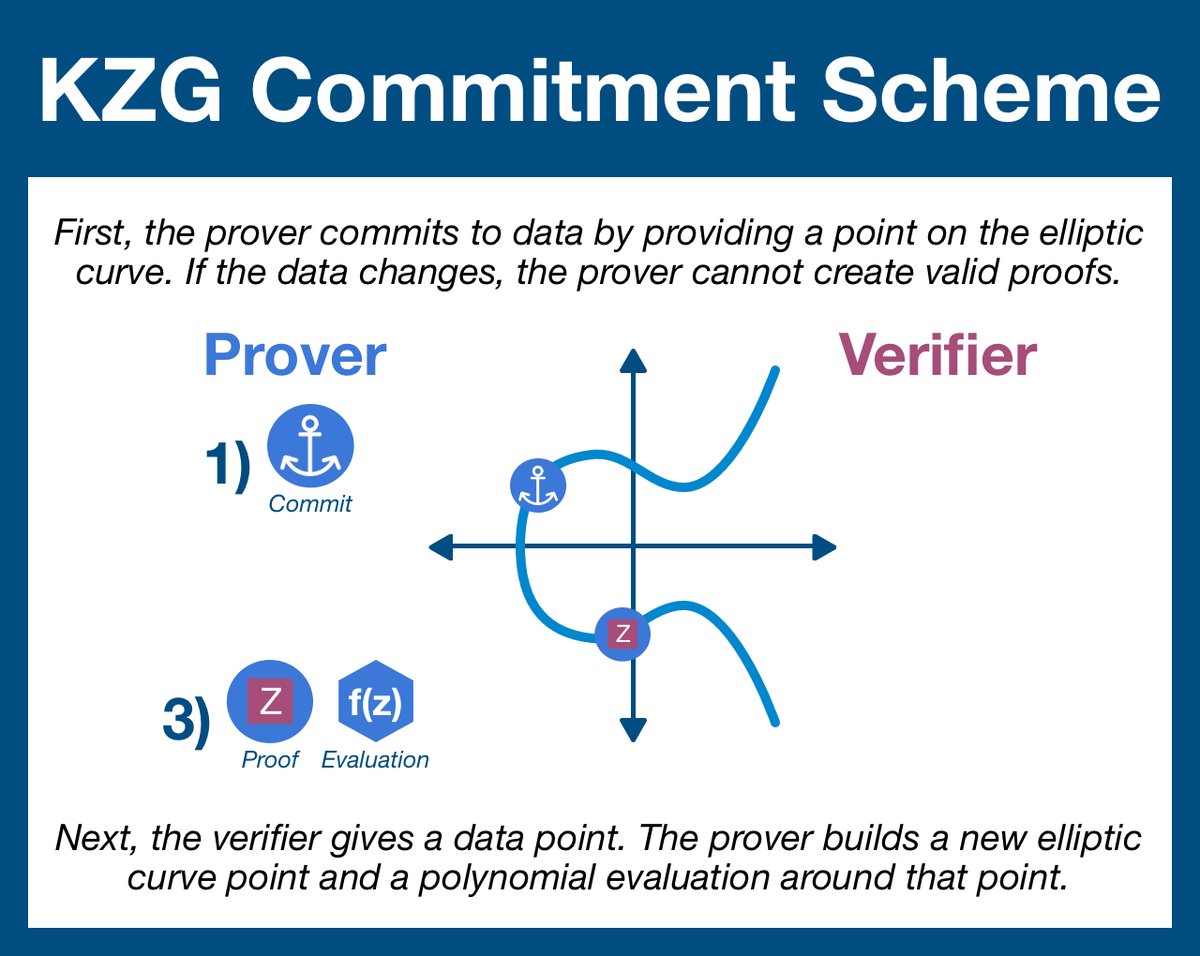

(7/22) The verifier (the party challenging the prover) knows at least one piece of data in the committed data set, and so requests a proof around data point z.

The prover calculates [h(S)] and f(z), returning the values to the verifier.

The prover calculates [h(S)] and f(z), returning the values to the verifier.

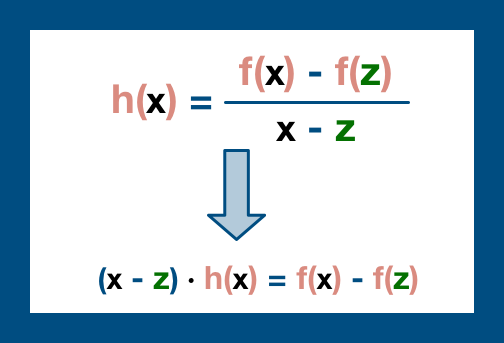

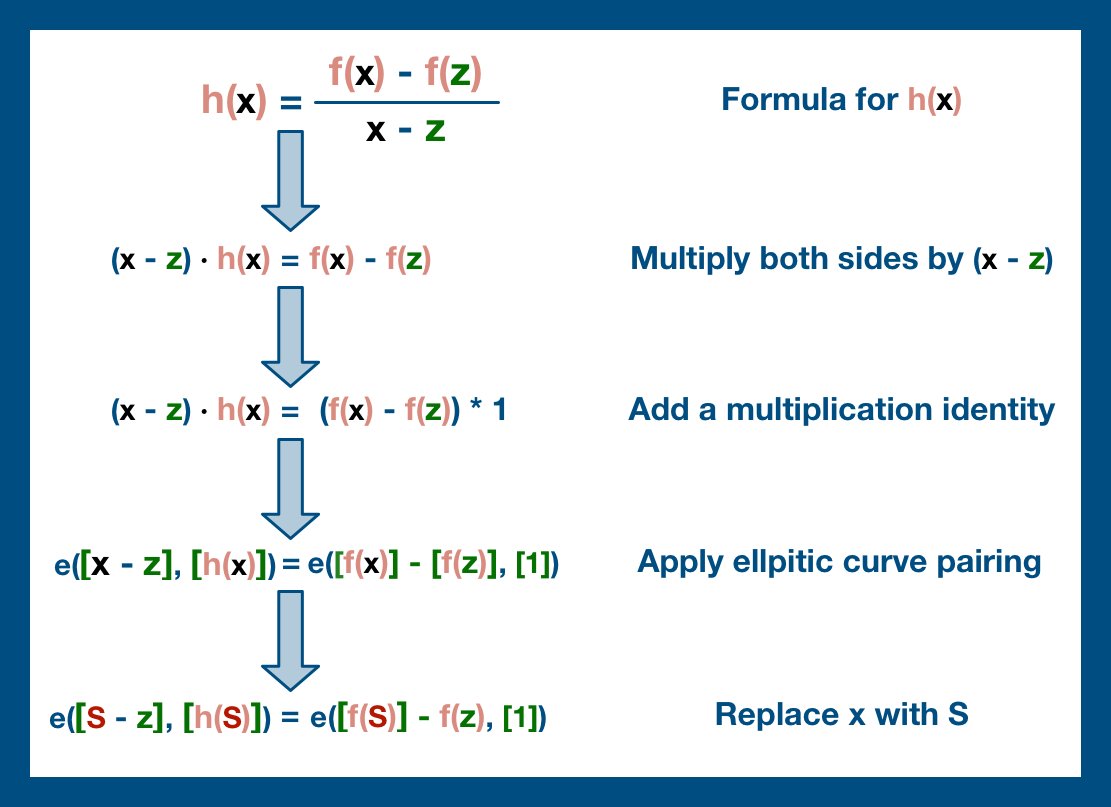

(9/22) The core of KZG commitment is this "h(x)" polynomial. If the prover is honest and is still committed to the original data, this is a simple polynomial to derive and to evaluate.

And so, we are simply going to test this polynomial by having the prover evaluate it at S.

And so, we are simply going to test this polynomial by having the prover evaluate it at S.

(11/22) But remember, we aren't working with standard functions; we are working with elliptic curves. And so, we have a problem.

We have seen that we can easily add and subtract two points on an elliptic curve, but we haven't seen multiplication.

We have seen that we can easily add and subtract two points on an elliptic curve, but we haven't seen multiplication.

(12/22) In fact, you CAN'T multiply two elliptic curve points, at least in any coherent way... not in any way that will non-destructively obscure data in the way we need.

Fortunately, we have a solution: elliptic curve pairings.

Fortunately, we have a solution: elliptic curve pairings.

(13/22) Pairings are perhaps the most advanced math you'll ever come across. Super exciting, cutting edge research-type stuff.

For our purposes, they are actually pretty easy: imagine pairings as the single use, irreversible version of elliptic curve point multiplication.

For our purposes, they are actually pretty easy: imagine pairings as the single use, irreversible version of elliptic curve point multiplication.

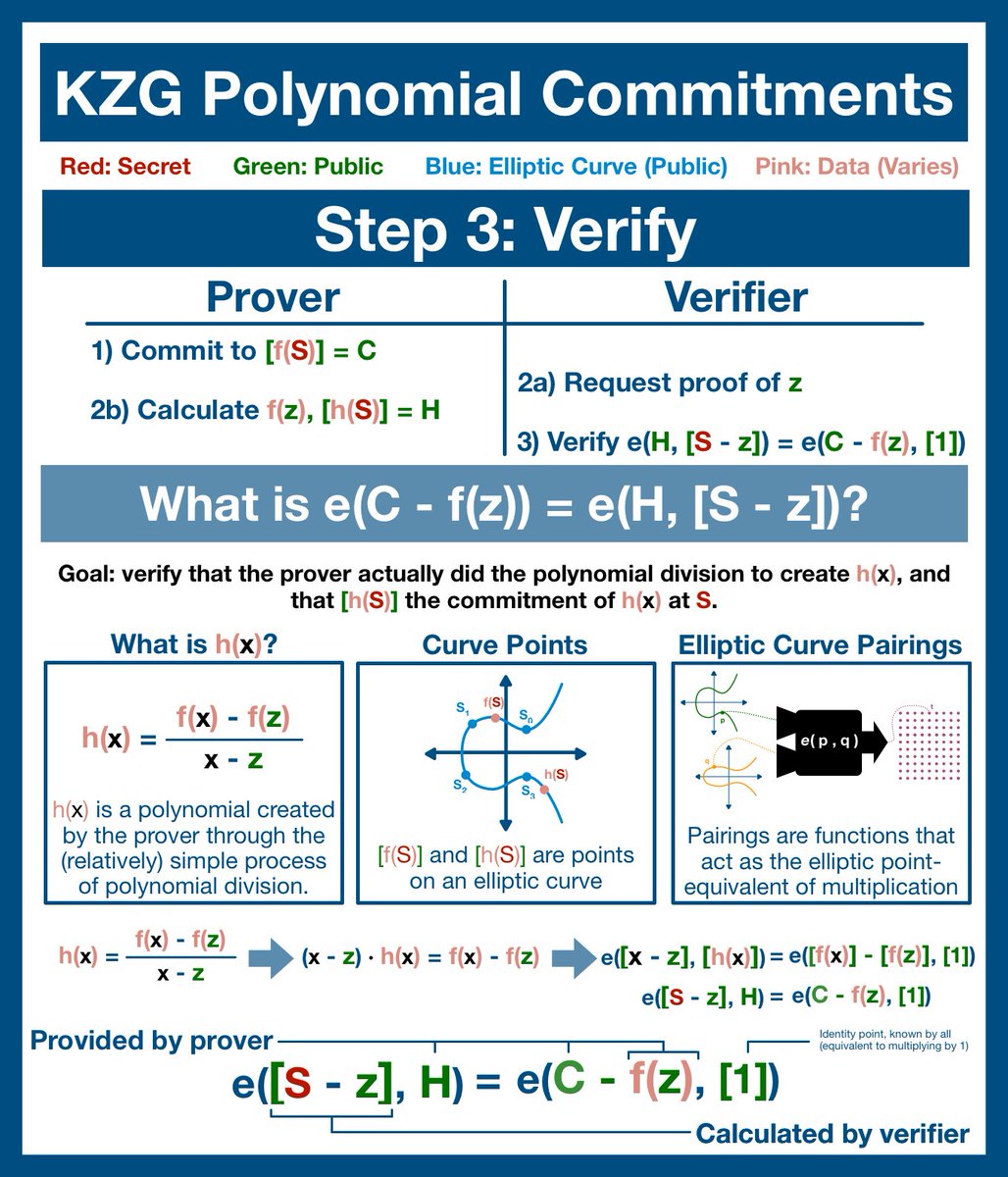

(16/22) And so, the verifier computes both sides of the equation and compares the results. If the results match, then we can be mathematically certain the prover was honest!

Need to unpack that one more time?

Need to unpack that one more time?

(17/22) The purpose of the verification is to work out whether the prover successfully divided the polynomial f(x) by (x-z). If any of the data was altered, the prover wont have access to f(x). He'll be able to generate a polynomial based off the new data, but it won't verify.

(18/22) Think like this:

Step 1: the prover committed to a dataset by creating a polynomial and evaluating it using the SRS

Step 2: the verifier challenges the prover by giving a data point within the original data set

(continued)

Step 1: the prover committed to a dataset by creating a polynomial and evaluating it using the SRS

Step 2: the verifier challenges the prover by giving a data point within the original data set

(continued)

(19/22)

Step 3: the prover comes back with two items, a curve point chosen using the prover's requested data point and an evaluation

Step 4: the prover uses a pairing to double check that these two items were correctly calculated, using the commitment as a reference.

Step 3: the prover comes back with two items, a curve point chosen using the prover's requested data point and an evaluation

Step 4: the prover uses a pairing to double check that these two items were correctly calculated, using the commitment as a reference.

(20/22) That's it, the entire KZG commitment scheme! Once the verifier has run both sides of the equation and checked for equality, the process is complete.

We've successfully verified both the original commitment and the specific data point within the committed dataset.

We've successfully verified both the original commitment and the specific data point within the committed dataset.

(21/22) In fact, KZG commitments are so powerful that we can actually verify more than one point at a time.

A KZG multiproof can prove huge amounts of data points (million+) just by providing a single group element.

But that's a topic for some other theadoor.

A KZG multiproof can prove huge amounts of data points (million+) just by providing a single group element.

But that's a topic for some other theadoor.

(22/22) And so, there you have it: The KZG Polynomial Commitment Scheme!

Now, let's go find somewhere to put them to use...

Now, let's go find somewhere to put them to use...

Like what you read? Help me spread the word by retweeting the thread (linked below).

Follow me for more explainers and as much alpha as I can possibly serve.

Follow me for more explainers and as much alpha as I can possibly serve.

Loading suggestions...

![(15/22) The prover supplies 3 of 4 terms needed in the verification expression:

- [f(S)], the commi...](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ffnf4U5VsAAOaC2.jpg)