Recorded on the walls of the temple of Denderah as an eighteen-day festival, it took place during the second half of the month of Khoiak, that is, during the period of the waning moon, culminating in the death of the old moon and rebirth of the new moon.

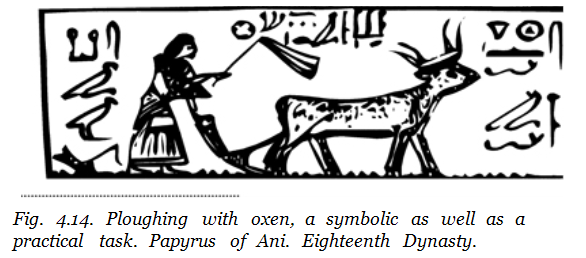

This was the equivalent of a north European spring festival, for it was at this time of the year that wheat and barley were sown, as well as many other crops requiring the milder weather of the Proyet months (the season of Coming Forth or Emergence).

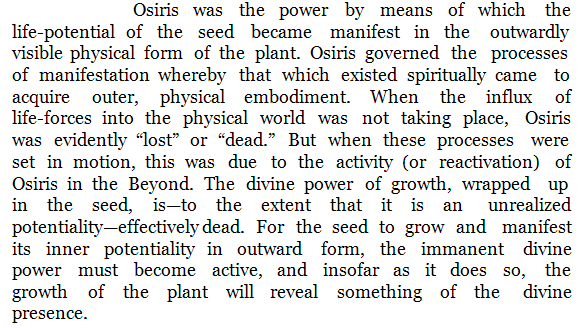

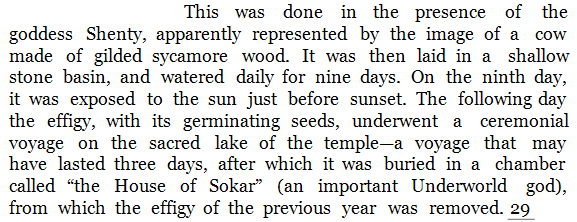

The festival of Khoiak seems to have been overwhelmingly Osirian in tone. For the common people, Osiris was apprehended in the grain, as its power of growth. It was he who “made corn from the liquid that is in him to nourish the nobles and the common folk.”

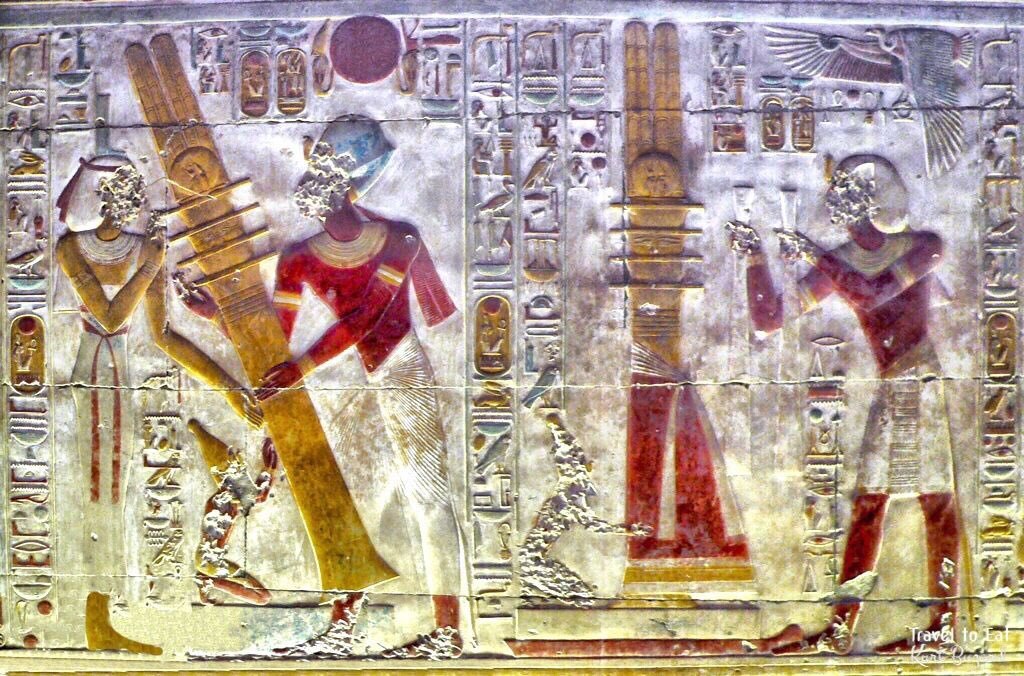

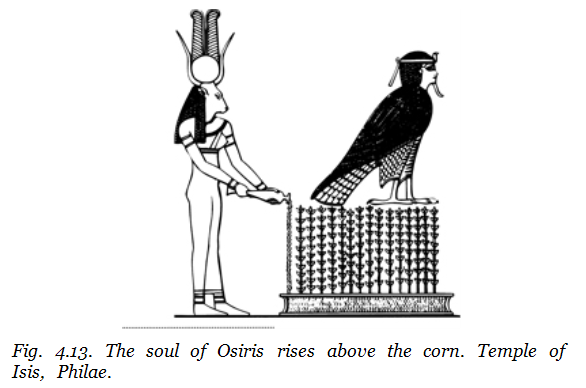

The relief illustrates the belief that as a result of the floodwaters having poured over the earth, not only do the seeds then grow, but the sprouting of the vegetation is also the “rising up” of Osiris.

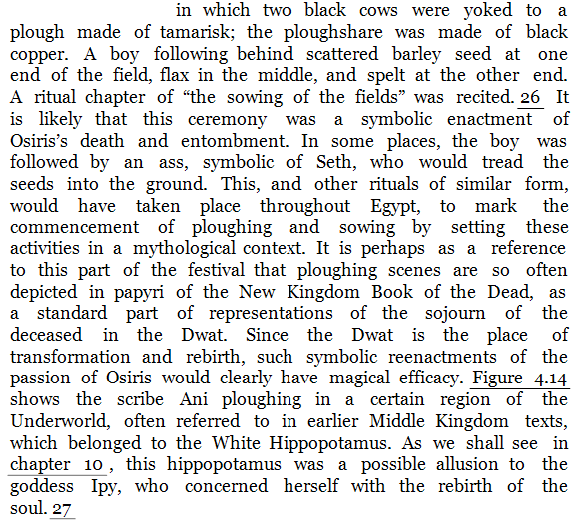

The implication is that the sowing of the seed was regarded as a burial or entombment of Osiris, prior to his “resurrection “ in the living plants. Plutarch’s report of the Egyptian peasant’s attitude to seed sowing supports this view:

“When they hack up the earth with their hands and cover it up again after having scattered the seeds, wondering whether these will grow and ripen, then they behave like those who bury and mourn.”

For the ancient Egyptians, there was an intimate relationship between the mythical and the natural worlds. In the mythical world was apprehended the true reality, within which the natural world participates.

The Osirian myth expresses in images the dovetailing of the two worlds, and through these images the relationship of the spiritual to the phenomenal levels of being can be experienced.

Osiris’s awakening involves the activation of the universal sexual energy from which all life arises. This sexual energy is mediated by Osiris in the Dwat, from whence it is channelled by him into the world.

The burial of the effigy occurred on the day of “the interment of Osiris,” the last day of the season of Inundation. This meant that the sprouting of the seed from the body of Osiris would have occurred in the burial chamber.

In the lunar calendar, the burial or interment corresponded to the last day of the waning moon. It is likely that since the first day of the month was the day during which the moon could not be seen, Osiris would on this day have been regarded as “lost.”

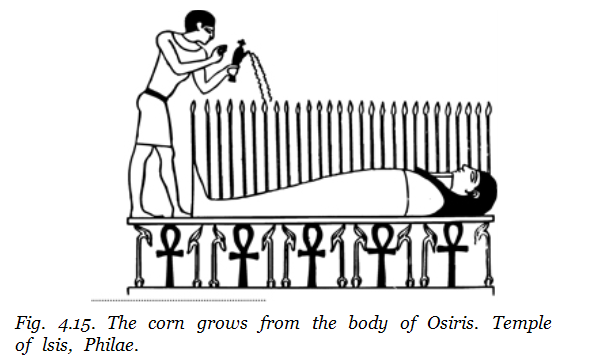

The next event in this sequence of rituals would then have occurred on the following day, the day of the new moon. This event was the raising of the djed column, symbolic of Osiris’s resurrection, and the renewal of the powers of life.

The raising of the djed brought in the new season of Proyet, and “opened” the year. Hence, despite its occurring in the fifth month, it was regarded as another New Year’s Day.

For the Egyptians, the flow of life-giving forces into the world of nature was dependent on the resurrection of Osiris “on the other side” in the spiritual realm of the Dwat.

It is for this reason that the festival of Khoiak was considered the most propitious time for the coronation of the king, the accession of Horus being profoundly related to the “resurrection” of Osiris.

The temple rituals ended with the first day of the season of Proyet. On this day there was a general celebration of festivities throughout Egypt. These would have been comparable to the north European May Day festivities.

To what extent the temple rites were generally reflected in the celebrations of the populace is hard to ascertain. All festivities would have been celebrated with different degrees of spiritual involvement.

While at the popular level the festival was Osirian, yet the understanding of the deeper mysteries concerning the presence of Osiris in the natural and spiritual worlds, and his relationship to the human soul, would have varied greatly.

To judge from Plutarch, however, we may suppose that the mass of the people would have lived in the radically different moods of mourning followed by rejoicing, which accompanied the passion and resurrection of the god.

Loading suggestions...