Viewing "war" as the central problem of international relations was well said by Robert Keohane in a review chapter from 2013: "The study of world politics starts with the study of war."

academic.oup.com

academic.oup.com

This is unsurprising, given how the modern discipline of international relations was impacted by World War I: a surge of funding and establishment of institutions after the war focused on understanding its causes and prevention.

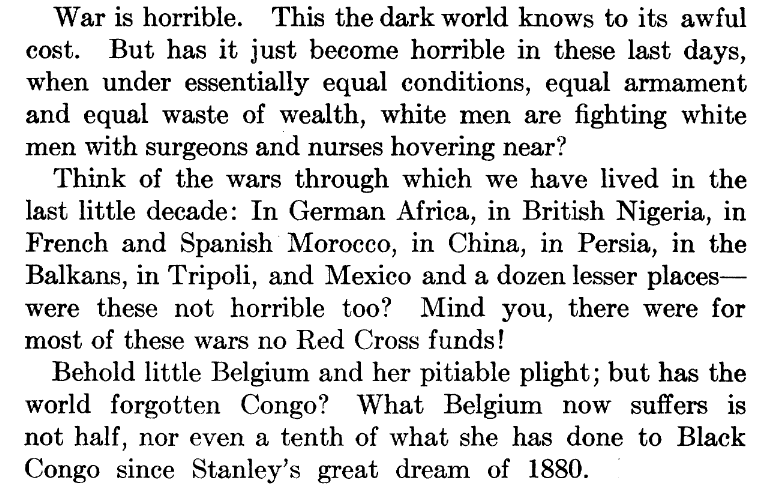

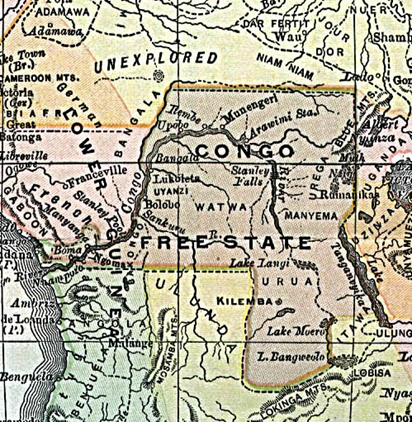

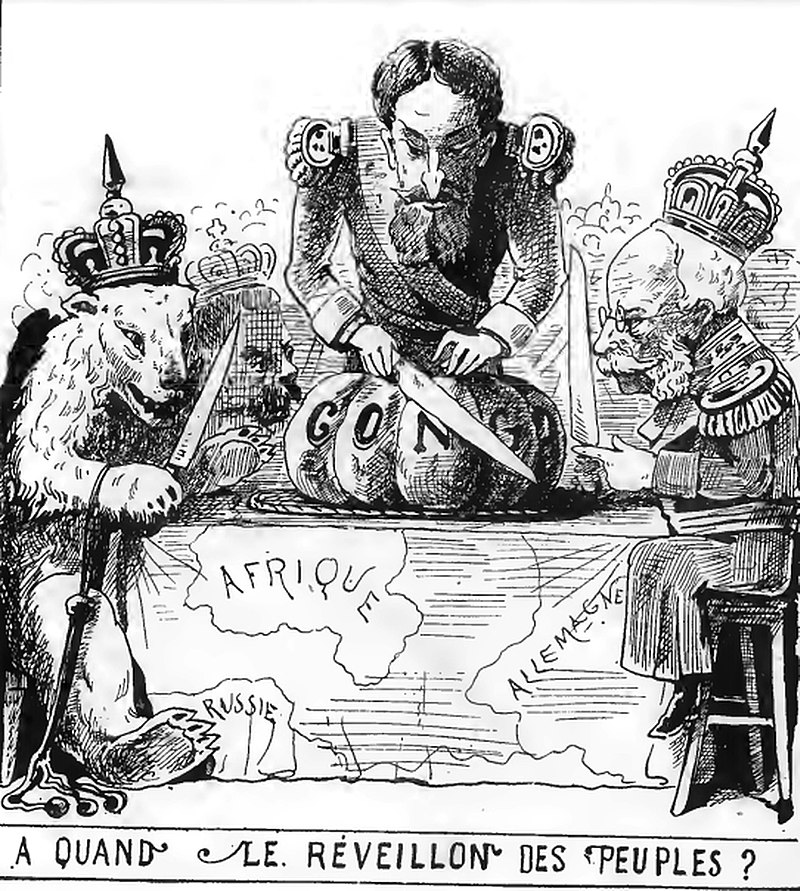

But I have my students consider an observation made by W.E.B. Du Bois in this 1917 piece.

Link: #metadata_info_tab_contents" target="_blank" rel="noopener" onclick="event.stopPropagation()">jstor.org

Link: #metadata_info_tab_contents" target="_blank" rel="noopener" onclick="event.stopPropagation()">jstor.org

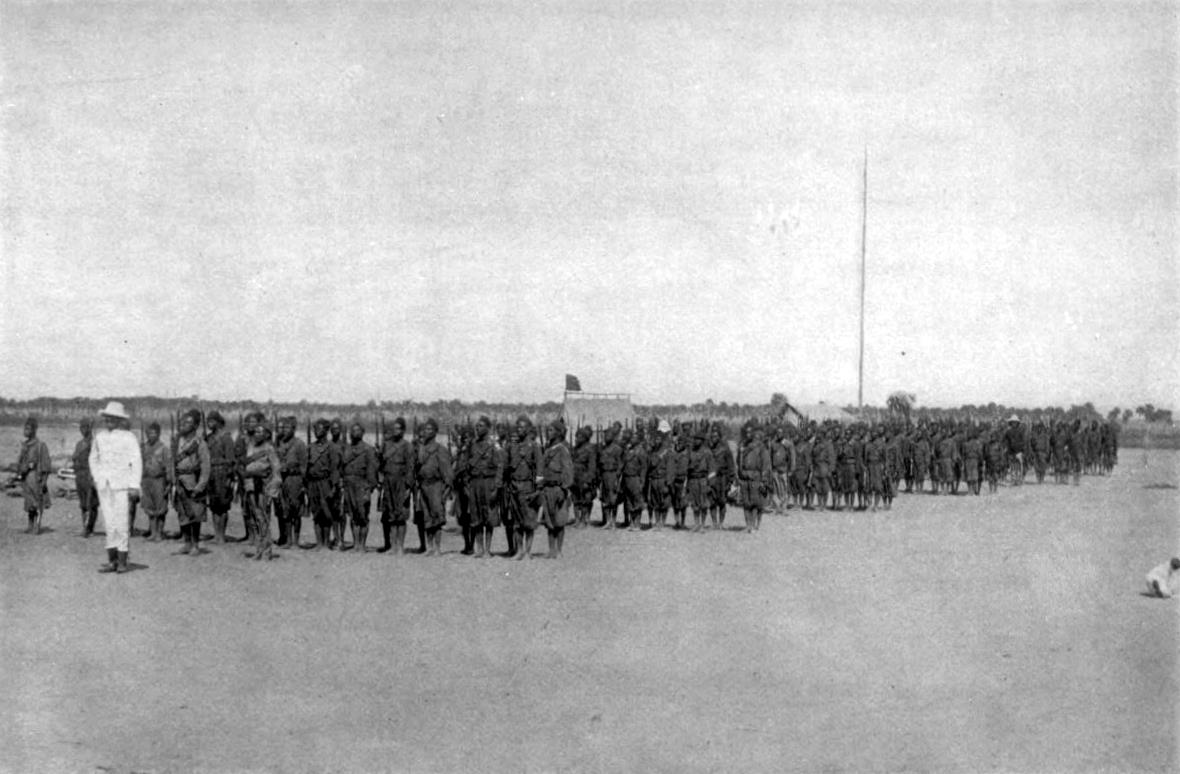

This contributed to misrule and neglect. In particular, the government allowed pandemics to rage in the region.

tandfonline.com

tandfonline.com

The combination of violence and disease meant that somewhere between 5 million and 12 million people died between 1885-1908 as a consequence of Belgian rule (most common estimate is 10 million).

amazon.com

amazon.com

Having given context to Du Bois' observation, I then pose the question: what if the tragedy in Congo, not World War I, was the event to garner widespread academic attention to the study of international politics?

To be clear, pre-World War I international relations scholarship WAS largely focused on colonial affairs, such as the need in the UK to adapt after the Boar War 👇.

But IR had not gained the attention (or resources) that it would garner following the war

amazon.com

But IR had not gained the attention (or resources) that it would garner following the war

amazon.com

How would IR be different if genocide (Congo) not war (Belgium) was its focus?

In class, we focused on two possible differences:

- No "Long Peace" or "Cold War" rhetoric

- No "Democratic Peace" prominence.

Let's unpack each.

In class, we focused on two possible differences:

- No "Long Peace" or "Cold War" rhetoric

- No "Democratic Peace" prominence.

Let's unpack each.

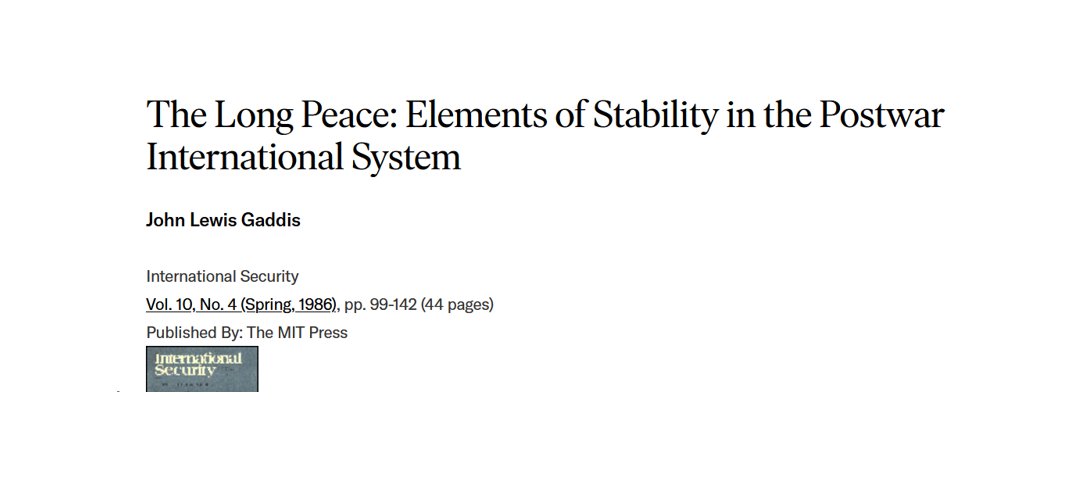

First, we wouldn't talk of a "Long Peace" following World War II.

This phrase was made popular by historian John Lewis Gaddis, first in a 1986 @Journal_IS article...

Link: jstor.org

Link: jstor.org

...and then in a 1989 book.

amazon.com

amazon.com

As he wrote in the article, "Given all the conceivable reasons for having had a major war in the past four decades – it seems worth of comment that there has not in fact been one….[We should try] comprehend how this great power peace has managed to survive for so long"

Such an idea feeds into the broader "decline of war" or "decline of violence" thesis.

amazon.com

amazon.com

The Cold War was, in truth, quite hot. True, we didn't have another war like World War II. But that doesn't mean the world witnessed a "Long Peace".

thenation.com

thenation.com

As Paul Thomas Chamberlin writes in his own history of the time period, "What would a broad history of the Cold War age look like, I wondered, if told from the perspective of the period’s most violent spaces?"

amazon.com

amazon.com

This says nothing about the wars that happened, AFTER the Cold War, such as in, again, Congo.

amazon.com

amazon.com

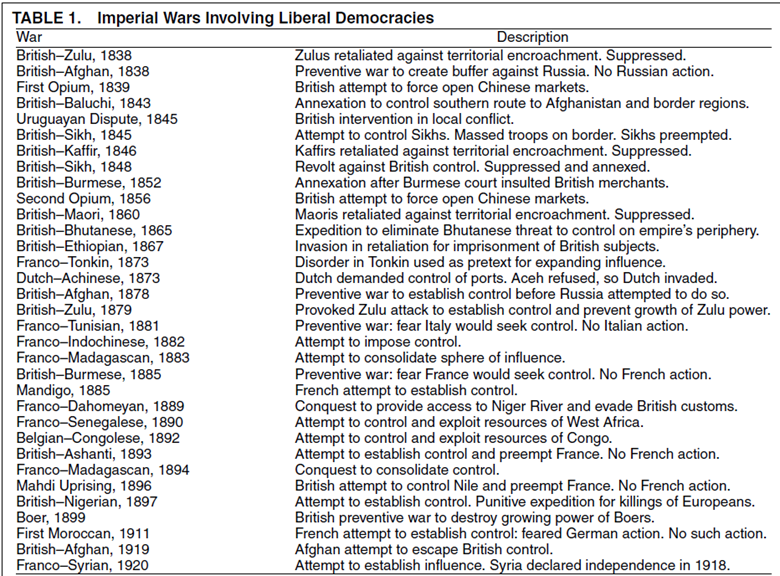

Second, we likely wouldn't talk (as much) about a "Democratic Peace".

That list comes from Sebastian Rosato's 2003 @apsrjournal paper critiquing the "Democratic Peace."

cambridge.org

cambridge.org

So while IR might still discuss how there is less conflict between democratic states (a finding that itself is worth unpacking), it likely be more of an interesting observation, rather than a core "empirical law" of the discipline.

Link: jstor.org

Link: jstor.org

While there other ways the discipline of IR would have changed (and likely also many ways in which it would be the same), the above gave my students a sense for how our ideas about international politics would be different if we had taken Du Bois' challenge seriously.

[END]

[END]

Loading suggestions...