Among Cleisthenes' reforms was the introduction of a process called ostracism.

Once a year the citizens were given the opportunity to exile a fellow citizen for ten years.

It was intended to prevent any one individual from becoming too powerful and threatening the democracy.

Once a year the citizens were given the opportunity to exile a fellow citizen for ten years.

It was intended to prevent any one individual from becoming too powerful and threatening the democracy.

Or, in the words of the historian Plutarch:

"Ostracism was not a penalty, but a way of pacifying and alleviating that jealousy which delights to humble the eminent, breathing out its malice into this disfranchisement."

Cleisthenes' idea showed some real foresight.

"Ostracism was not a penalty, but a way of pacifying and alleviating that jealousy which delights to humble the eminent, breathing out its malice into this disfranchisement."

Cleisthenes' idea showed some real foresight.

In this way it was really a stabilising process. For exile was better than death, and any ostracised citizen could return after those ten years had passed with no other penalties or punishments.

Neither their wealth nor property was confiscated, nor their citizenship revoked.

Neither their wealth nor property was confiscated, nor their citizenship revoked.

So it was simply a way of removing a powerful individual from the political system for a while.

This cooled their support, stopped any reforms they had put in motion, and - perhaps crucially - prevented that citizen, his supporters, and his enemies, from turning to violence.

This cooled their support, stopped any reforms they had put in motion, and - perhaps crucially - prevented that citizen, his supporters, and his enemies, from turning to violence.

The only limitation was the vote had to be quorate, which according to Plutarch meant at least 6,000 votes in total.

That two month gap was also important, as it prevented an impulsive, angry vote, and gave time for discussion (or manipulation?) to shape the public discourse.

That two month gap was also important, as it prevented an impulsive, angry vote, and gave time for discussion (or manipulation?) to shape the public discourse.

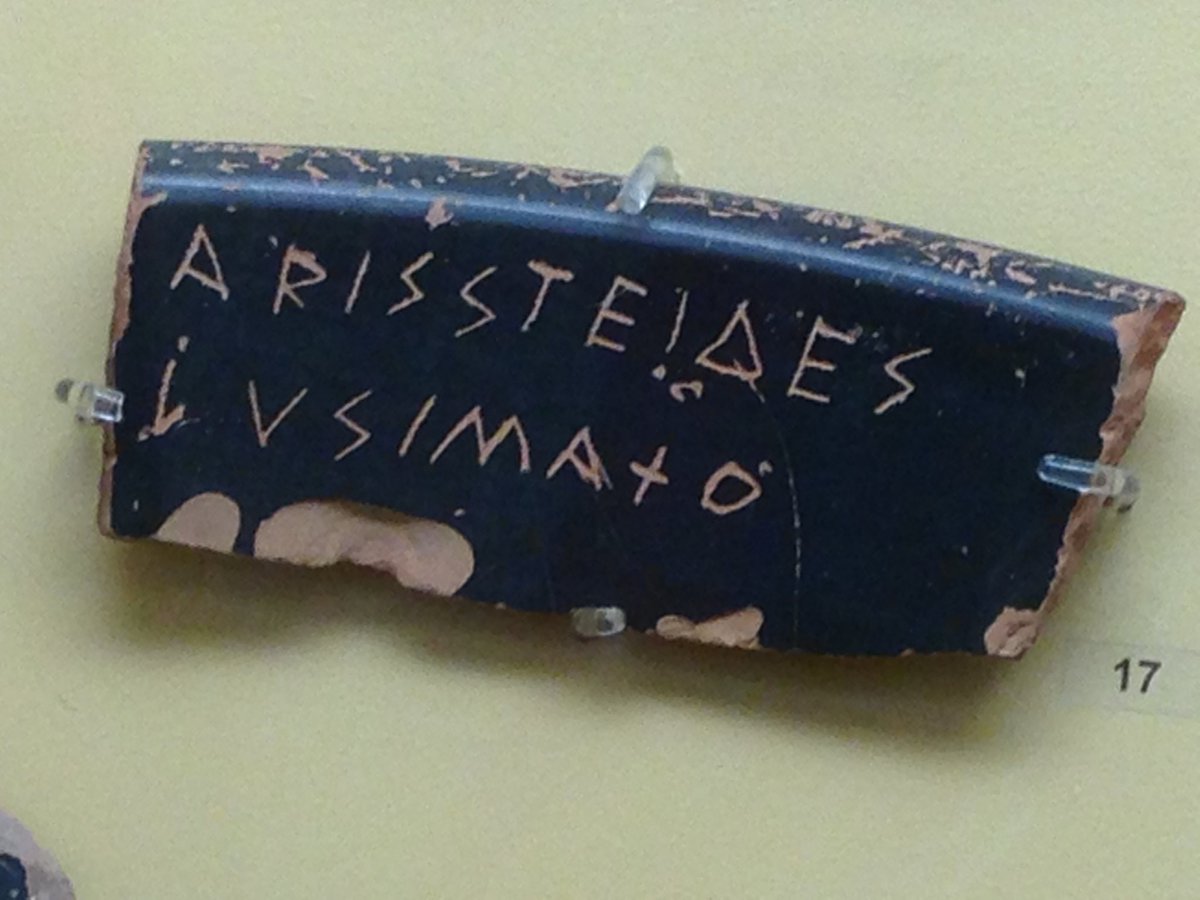

When Aristides left the city he is alleged to have issued a prayer that no citizen of Athens would have have cause to remember his name or to regret ostracising him.

Perhaps apocryphal, but testament to his famed virtue.

Perhaps apocryphal, but testament to his famed virtue.

Ostracism was finally abolished in 416 BC when a man called Hyperbolus was ostracised.

See, Hyperbolus was basically a nobody. His only talent was agitating crowds, causing offense, and making trouble.

See, Hyperbolus was basically a nobody. His only talent was agitating crowds, causing offense, and making trouble.

At the time he was calling for an ostracism, as party politics in Athens had become once again heated, split between the aristocratic Nicias and the democratic Alcibiades, two bitter enemies.

In the end an ostracism was called. But the enemies came up with a plan...

In the end an ostracism was called. But the enemies came up with a plan...

But the citizens were disgusted by this. They felt that their longstanding and vital right to ostracise powerful citizens had essentially been stolen by Nicias and Alcibiades.

Hyperbolus was an agitator, not a serious statesman or political heavyweight. It seemed wrong.

Hyperbolus was an agitator, not a serious statesman or political heavyweight. It seemed wrong.

And, as Plutarch puts it, the citizens felt that Hyperbolus wasn't worthy of ostracism.

Despite being a major blow to any statesman's career, there was a certain honour and nobility in being ostracised. It was only for great leaders whose greatness had become a threat.

Despite being a major blow to any statesman's career, there was a certain honour and nobility in being ostracised. It was only for great leaders whose greatness had become a threat.

Plato (the poet, not the philosopher) said this about the ostracism of Hyperbolus:

"And yet he suffered worthy fate for men of old;

A fate unworthy though of him and of his brands.

For such as he the ostrakon was ne'er devised."

And so ostracism was abolished.

"And yet he suffered worthy fate for men of old;

A fate unworthy though of him and of his brands.

For such as he the ostrakon was ne'er devised."

And so ostracism was abolished.

The political situation in Athens had also changed. Whereas in the early 5th century BC it was individuals who seemed to pose the greatest threat to Athenian democracy, by the end it was oligarchial coups backed by foreign powers - as Sparta briefly did to Athens in 404 BC.

So, was it a good idea? That's hard to say.

It certainly seems that ostracism was an effective outlet for political unrest, nipping it in the bud before things became too serious.

For despite constant political tensions throughout the 5th century, Athens remained stable.

It certainly seems that ostracism was an effective outlet for political unrest, nipping it in the bud before things became too serious.

For despite constant political tensions throughout the 5th century, Athens remained stable.

And the fact that it wasn't used gratuitously - ostracisms were relatively rare, given the length of time the process was in place - suggests that the citizens had respect for it.

They didn't abuse this right; it was saved for situations when it seemed truly necessary.

They didn't abuse this right; it was saved for situations when it seemed truly necessary.

Loading suggestions...