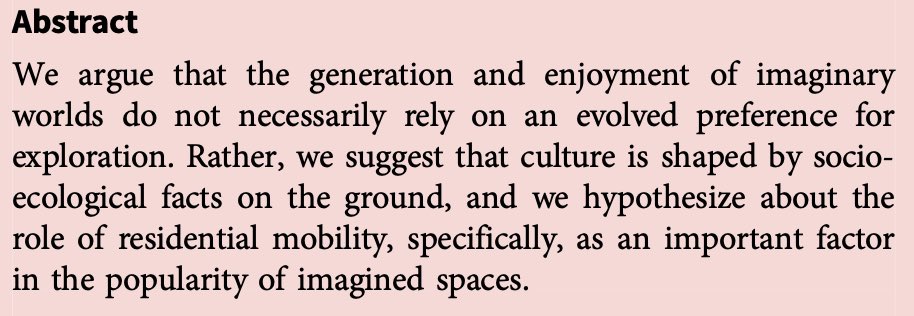

Why this long thread? Because our @BBSJournal Target Article was just released, in which with Nicolas Baumard we put forward a general hypothesis about the psychological foundations of fictions with imaginary worlds. (3/74)

And this Target Article comes with no less than 33 fascinating commentaries by scholars coming from a wide range of disciplines, from psychology to philosophy, anthropology, neuroscience , history, literature , biology… (4/74)

This is what #Tolkien thought, when he wrote "Part of the attraction of The Lord of the Rings relies on the intrinsic feeling of reward we experience when viewing far off an unvisited island or the towers of a distant city". (7/74)

But also @ShigeruMlyamoto, the creator of #Zelda who stated that "he wanted to create a game world that conveyed the same feeling you get when you are exploring a new city for the first time". (8/74)

At the ultimate level, cognitive and spatial exploration is a kind of long-term investment: you incur costs now, hoping to discover information that will be beneficial in the future. This strategy is costlier in harsh environments, because: (15/74)

(1) it is risky: one may not find any valuable information or innovative ideas, and come back empty handed (which is costlier with no secure amount of resources to begin with); (16/74)

(2) it is time- and energy-consuming, and therefore represents big opportunity costs: in harsh environments one is better off spending time and energy in more pressing needs; (17/74)

(3) it is a future-oriented strategy: one shouldn’t invest in information valuable only in the long-term in a dangerous environment. (18/74)

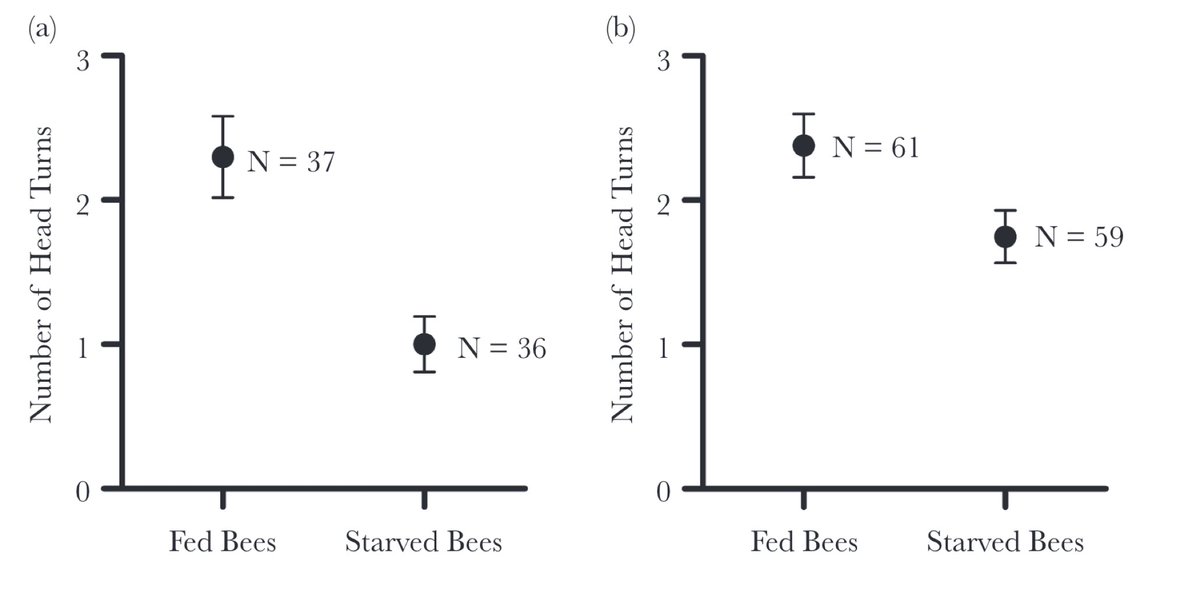

To sum up, exploration is a better strategy in conditions of relative safety. Importantly, its means that organisms living in scarcity explore less because exploitative strategies are better adapted to that type of environment. (19/74)

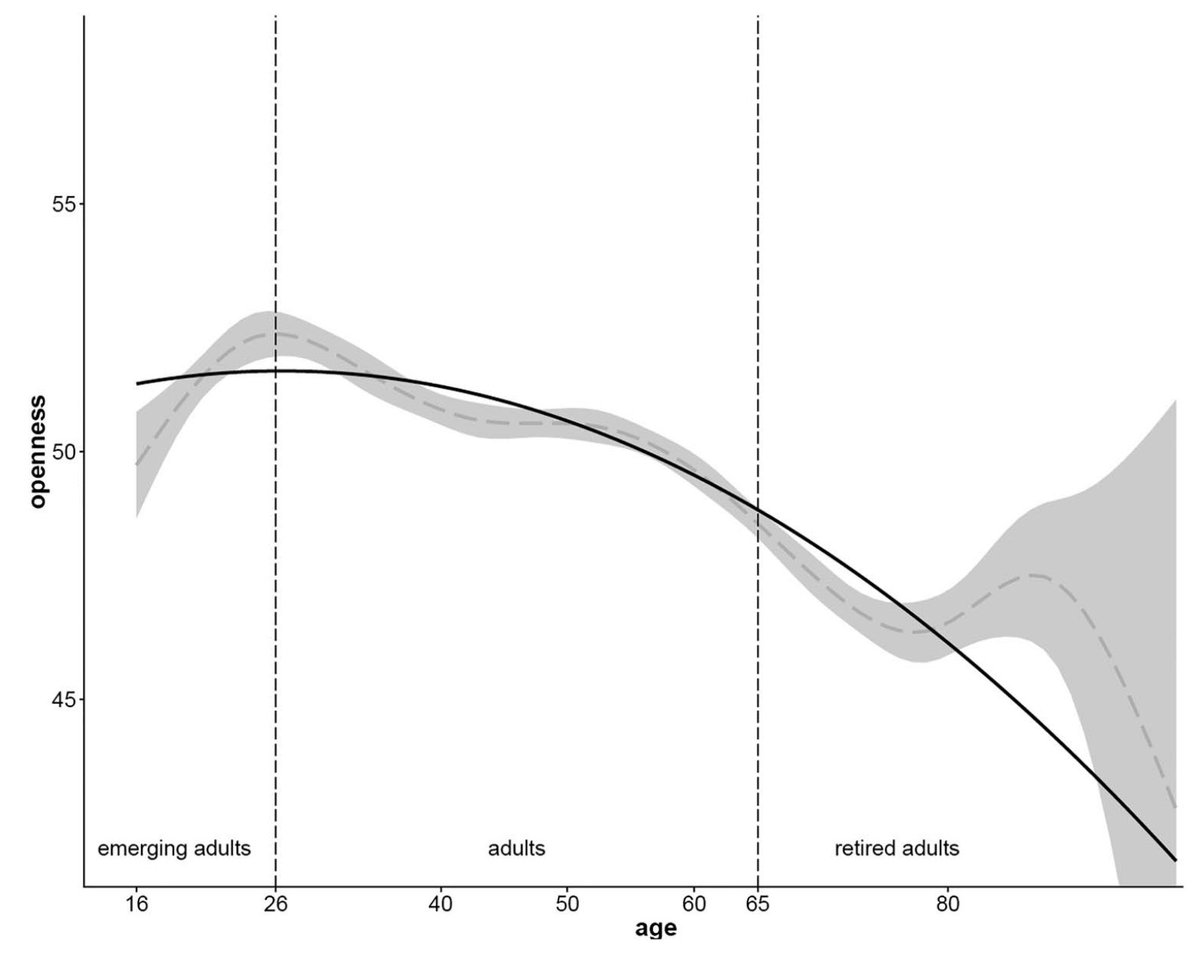

Of course variation in curiosity is not fully explained by ecological variation. Curiosity also varies with age. Typically, organisms go through an early period of exploration followed by a later period of exploitation (a developmental division of labor). (24/74)

More precisely, exploratory preferences increase continuously until adolescence and start to decrease then. (25/74)

Coming back to the cultural domain and our main hypothesis, we therefore predicted that: people (1) higher in Openness, (2) younger, and (3) living in more affluent and secure contexts should enjoy more fictions with imaginary worlds. (30/74)

This theory could therefore explain why imaginary worlds emerged recently in history. A large enough number of potential consumers had to be better-off, and therefore curious enough, for such fictions to be interesting and appealing to a broad audience. (32/74)

In the paper, we develop further this exploration hypothesis, its implications on culture, and we derive more predictions, for instance about the exaggeration of cultural content (the stimulus-intensification hypothesis). (34/74)

Commentators proposed many alternative explanations or corrections to our models. Here there are, with for each of them the short abstract. (35/74)

@sarahruthbeck and Paul Harris point to important future directions in developmental psychology, while specifying what kind of imaginative thinking emerge at what ages. (37/74)

While we focus on the neurotypical population, @zoophilosophy and Veit rightfully extend our framework to autistic people and the cultural implications of higher systemizing quotient. (38/74)

We agree with @rebeccadunk and Mar that, Openness being the driver of our preference for imaginary world, our model should be revised and focus on information-seeking cognition (not spatial exploration when it is for reward). (40/74)

@abazuel and Gomez extends our framework and proposes that imaginary worlds "provide us with what the physical world offered our ancestors: a sense of potentiality, and a key to the unknown". (41/74)

Gabriel, Green, Naidu, and @DrEParavati offer a complementary hypothesis: imaginary worlds offer opportunities to connect with others. We agree. However, this seems true of any entertaining device, not just for those set in imaginary worlds. (42/74)

@SeanPGoldy and Piff rightfully detail the proximate domain of our framework, convincingly arguing that ‘awe’ is a central emotion in information-seeking cognition (prompting exploration by rewarding the realization of big knowledge gaps). (43/74)

@adlightner , @Cynthiann_H and @ed_hagen develop further the creators’ evolutionary costs and benefits: creators of imaginary worlds receive reputational benefits because they become some kind of knowledge specialist. (45/74)

We completely agree with Norman and @ThaliaGoldstein that all fictions, even those set in real settings, prompt exploration (we argue this is a matter of degree), and that distance from reality should be further investigated. (49/74)

@angelanyh and Lee persuasively argue that young children may not enjoy imaginary worlds, not because they don’t enjoy new information, but because they don’t enjoy fiction that much. (50/74)

@KeithOatley propose to extend our theoretical framework by including more kinds of informational input, such as information about novel objects or new characters. (51/74)

Pianzola, Riva, Kukkonen and @FabryCom rightfully point to gaps in our model, that we should investigate next, notably the way the imaginary world is presented in the fiction, prompting (or not) a feeling of presence. (52/74)

@CatherineSalmon and Burch rightfully point to potential future research directions about sex-related differences in preferred kinds of exploration and, therefore, preferred fictional genres. (54/74)

@MorbidPsych and @MathiasClasen convincingly argue that we are curious about new threats in imaginary world, triggering our morbid curiosity (an important additional explanatory factor in our model). (56/74)

@andrewshtulman grounds our hypothesis in the broader theory that studies counterintuitive cultural content, and provide many arguments and examples in favor of the entertainment hypothesis. (57/74)

@oleg_sobchuk rightfully discusses the granularity of our definitions: we agree that the appeal of novel information (not just spatial) explain the success of imaginary worlds. (59/74)

Solin and @DrMarkGriffiths propose that, in video games especially, self-exploration is also appealing: people can safely experiment in imaginary worlds. (61/74)

@danicajwilbanks , @jordan_w_moon , Stewart, @kurtjgray, and Varnum defend and summarize a general adaptive view of fiction, closer to the simulation hypothesis, which is an alternative to the entertainment hypothesis. (64/74)

Wylie, @alix_alto , and @ana_gram_ argue that imaginary words enable coordination around shared moral values (we agree and add that association between Openness and Leftist ideology could be further studied). (67/74)

(3) We emphasize the idea that what matters to explain the cultural evolution of fiction are broad trends of psychological changes in potential audiences, notably evoked by changes in ecological conditions. (70/74)

I deeply thank all the commentators for such a fruitful and useful discussion, but also @paulbloomatyale and the original reviewers for their feedback and help in improving different versions of the Target Article. (71/74)

And many thanks to @Sacha_Altay , @BoonFalleur , @ValerianChambon , @Charlesddamp , @LFitouchi , @OliverWithAnI, @hugoreasoning, and @V_Thouzeau. And of course to Nicolas Baumard my co-author and supervisor. (72/74)

All images and graphs in this thread come from studies that are cited in the article. Please do ask if you want the precise references (which are sadly impossible to mention in a twitter thread). (73/74)

Thanks, especially if you ended up reading the whole thread… and don’t hesitate to send me feedback, questions, or comments, or to ask for the Target Article. (74/74)

Loading suggestions...