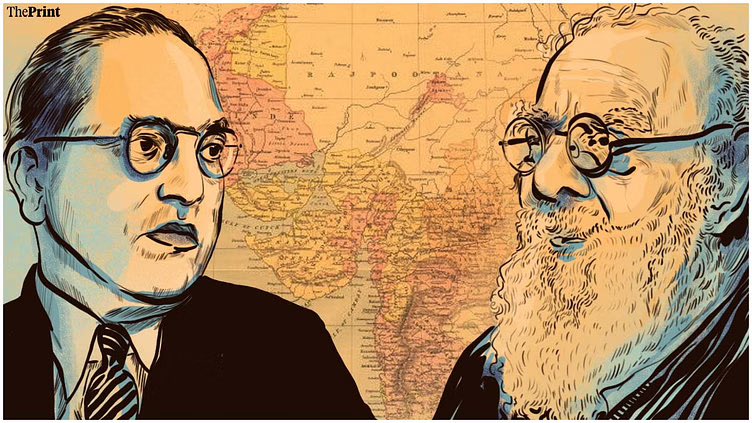

Why did Bengal or the Hindi-speaking states of north India fail to produce any important social reformer and anti-caste leader worth their name during the colonial period?

What happened in Bengal and the north? The difference between Bombay and Madras presidencies and the Bengal presidency—which included a large part of Hindi-speaking areas—on the issue of social reform was quite stark.

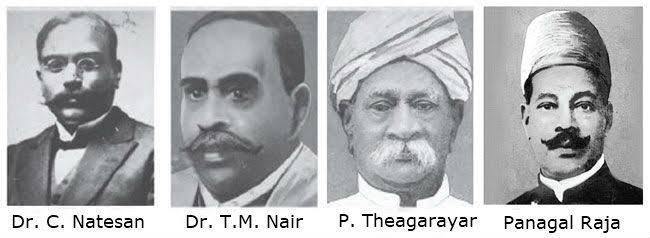

Interestingly, Gail Omvedt came to India to study the anti-caste movement and found that the old Bombay presidency was the most fertile ground for her study. She wrote her thesis—Cultural Revolt in a Colonial Society: A Non-Brahmin Movement in Western India. @PatankarPrachi

Why was nothing similar happening in north India and Bengal? The caste system and its brutality were equally, if not more, pervasive in the north and in Bengal. Despite that, no major lower or middle caste reform movement took place in these areas during the colonial period.

This paradox can be explained through three main arguments.

In north India, the population of the Brahmins and other dominant castes was comparatively more. So, it was not easy for the oppressed castes to revolt against the Hindu social order.

-Due to the Bhakti movement and also because of the enlightenment of the Bengali ‘Bhadralok’ castes, the character of caste oppression in the north was not so crude and blatant. We have no evidence to prove this hypothesis.

-In southern India or the Deccan, the Hindu social order was/is mainly in the form of a binary. In this binary, the Brahmins are at the top and Shudras/Ati-Shudras form the bottom. Whereas in the north and Bengal social hierarchy, there was a buffer of other upper castes.

The role of land and education

As the lack of anti-caste social reform movements in north India and Bengal is almost an unexplored topic in academia, I am providing another explanation in the form of a hypothesis.

As the lack of anti-caste social reform movements in north India and Bengal is almost an unexplored topic in academia, I am providing another explanation in the form of a hypothesis.

My argument is that this phenomenon has something to do with land titles and the differential access to English education.

In Bengal and Bihar, the British had implemented the Permanent Settlement plan by 1793 and Zamindaris were allotted to the elites. These Zamindars were the intermediaries through whom the British ruled and also collected land revenue.

In this system, land ownership rights were not given to the farmers. Whereas in Bombay and Madras presidencies, the Ryotwari system was in place. In this system, the farmers were the landowners and the British used to collect land revenue directly from them.

This might be the reason that a non-Brahmin middle class emerged in the Deccan, which later became the vanguard of the anti-caste movement. It’s interesting to note that most of the anti-caste leaders of the Deccan belonged to the peasantry or were government contractors.

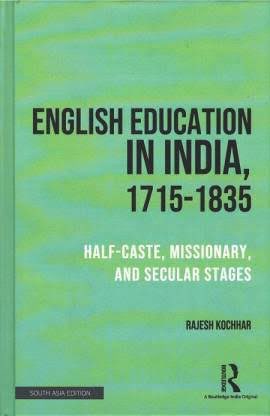

“In Bengal, where the permanent settlement of land revenue has been effected, the landlords acted as a buffer between the government and the actual tillers. Here the Governor General was very keen that demand for English education should come from the Indians themselves.”

“But in Bombay, where the system prevailed, the government wished to educate the peasants, so that they can understand the intentions of the government regarding them and keep their own accounts.”

“In Bombay, the native education, in vernacular and in English, received encouragement and patronage from the government itself.”

Universalisation of education, improving the condition of peasants, educating all girls and eradicating superstitions or eradicating caste never became the agenda of Bengali reformers.

The policy of providing English education only to elite Hindus ensured that the middle and lower caste peasantry in this region never came across European ideas of modernity like equality and fraternity.

Loading suggestions...