Propositions of the form "if A, then B" are called implications.

They are written as "A → B", and they form the bulk of our scientific knowledge.

Say, "if X is a closed system, then the entropy of X cannot decrease" is the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

They are written as "A → B", and they form the bulk of our scientific knowledge.

Say, "if X is a closed system, then the entropy of X cannot decrease" is the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

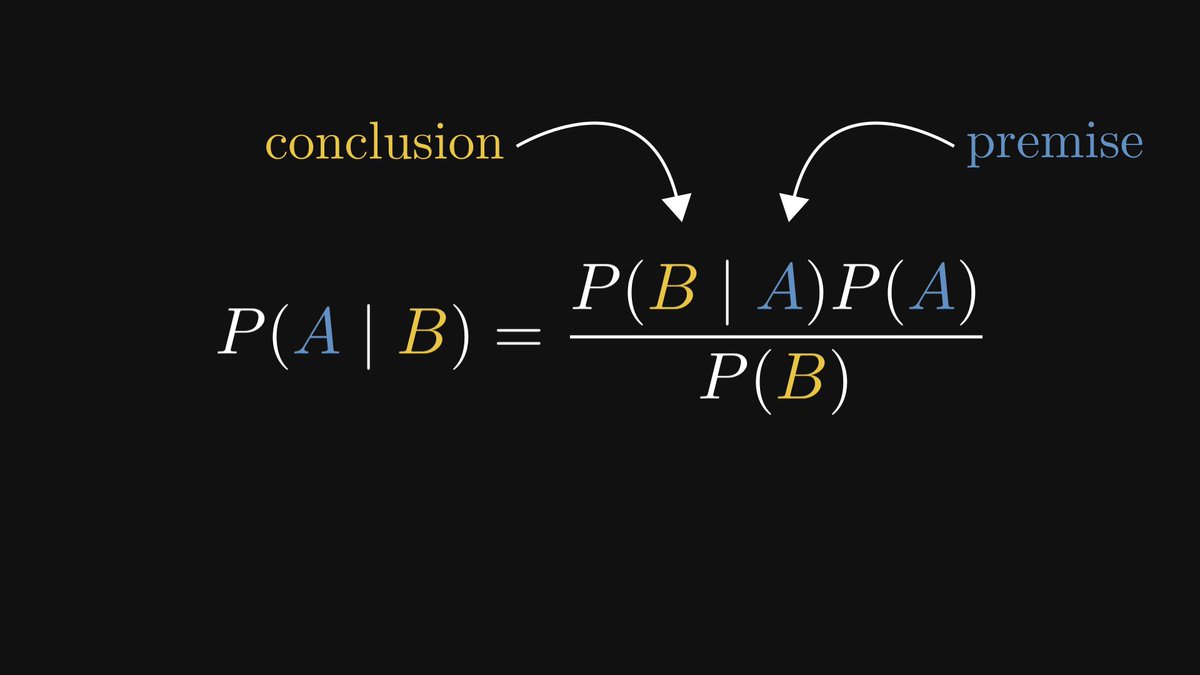

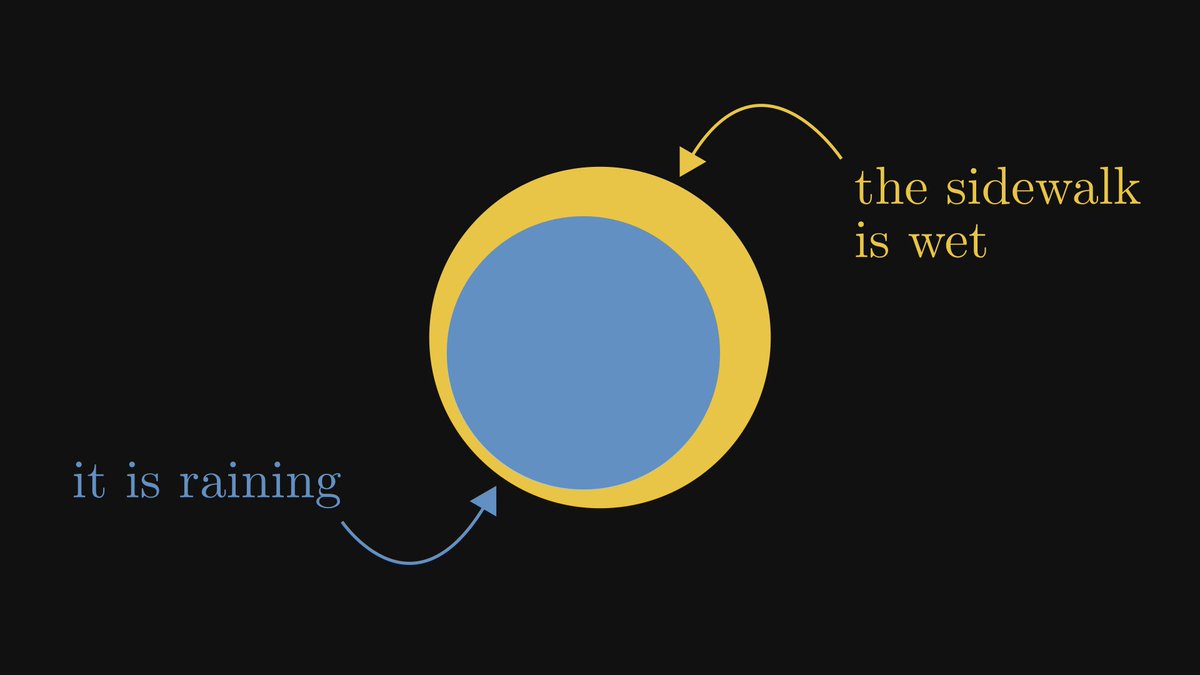

In the implication A → B, the proposition A is called "premise", while B is called the "conclusion".

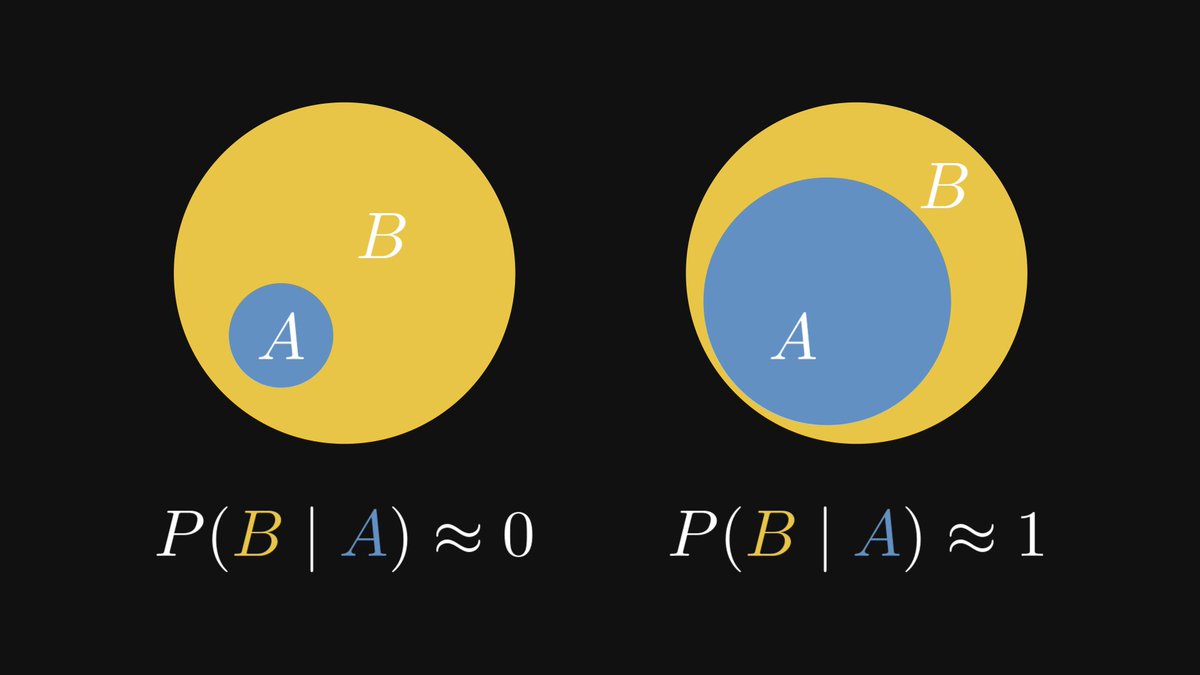

The premise implies the conclusion, but not the other way around.

If you observe a wet sidewalk, it is not necessarily raining. Someone might have spilled a barrel of water.

The premise implies the conclusion, but not the other way around.

If you observe a wet sidewalk, it is not necessarily raining. Someone might have spilled a barrel of water.

This thread is part of the latest issue of The Palindrome, the newsletter I have launched recently.

If you have enjoyed this explanation, check out the full post and share it with your friends!

thepalindrome.substack.com

If you have enjoyed this explanation, check out the full post and share it with your friends!

thepalindrome.substack.com

Loading suggestions...