Our journey ahead has three milestones. We'll

1. generalize the concept of a vector,

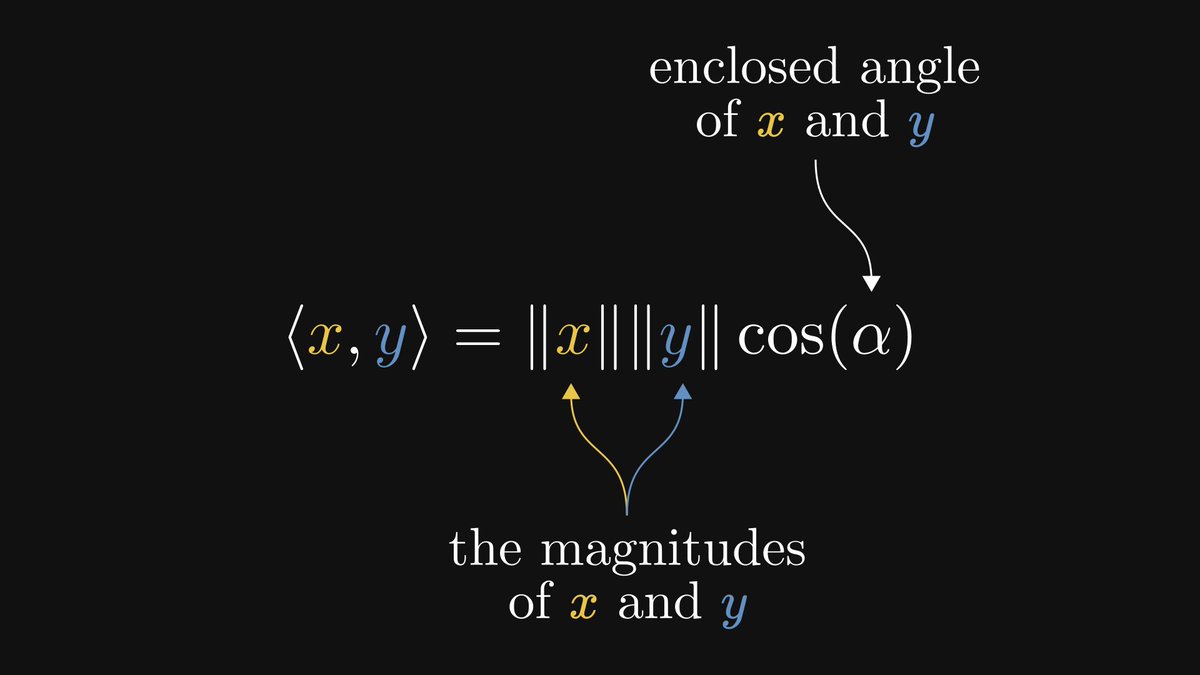

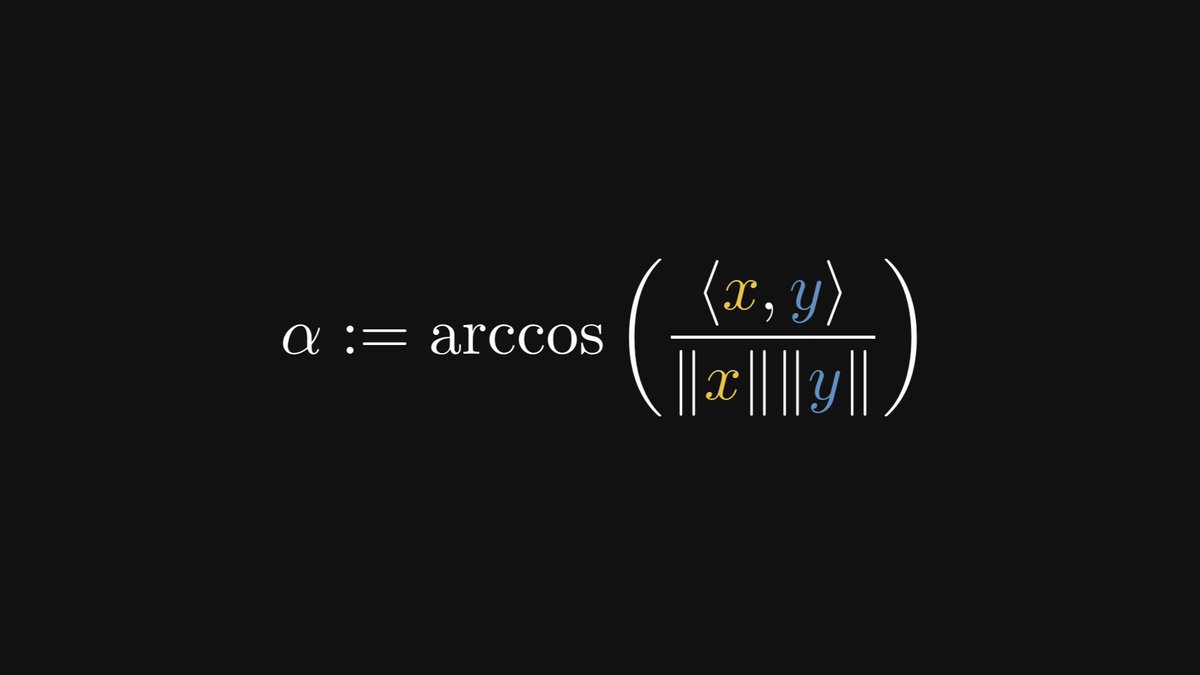

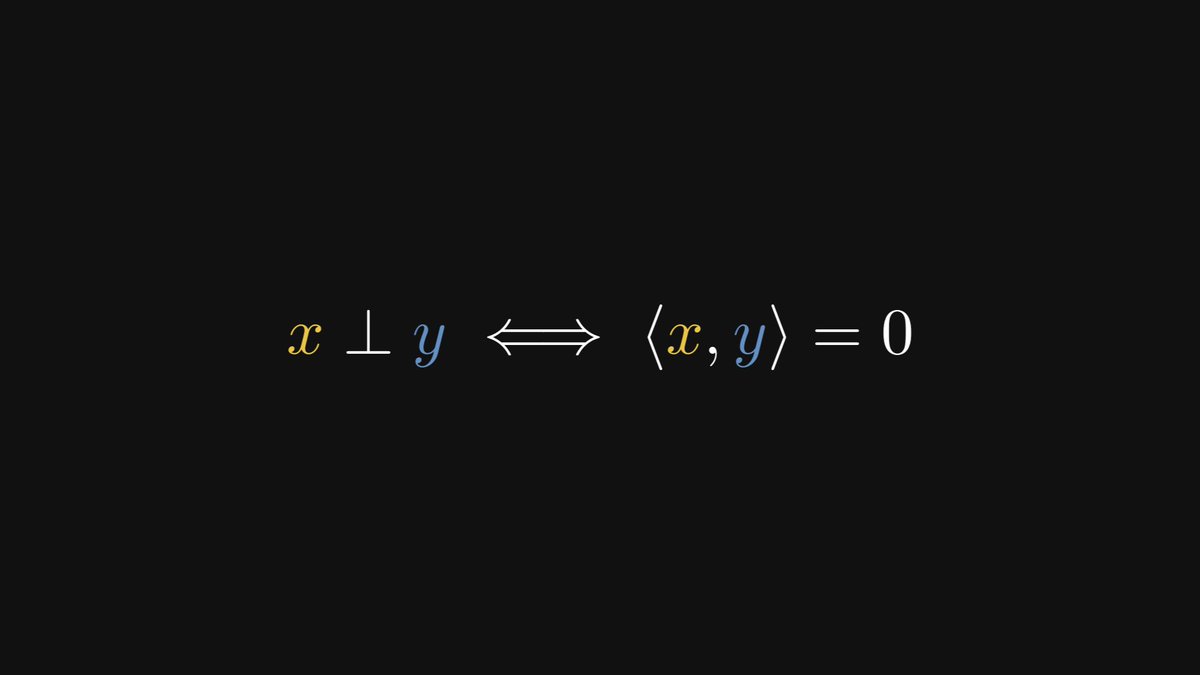

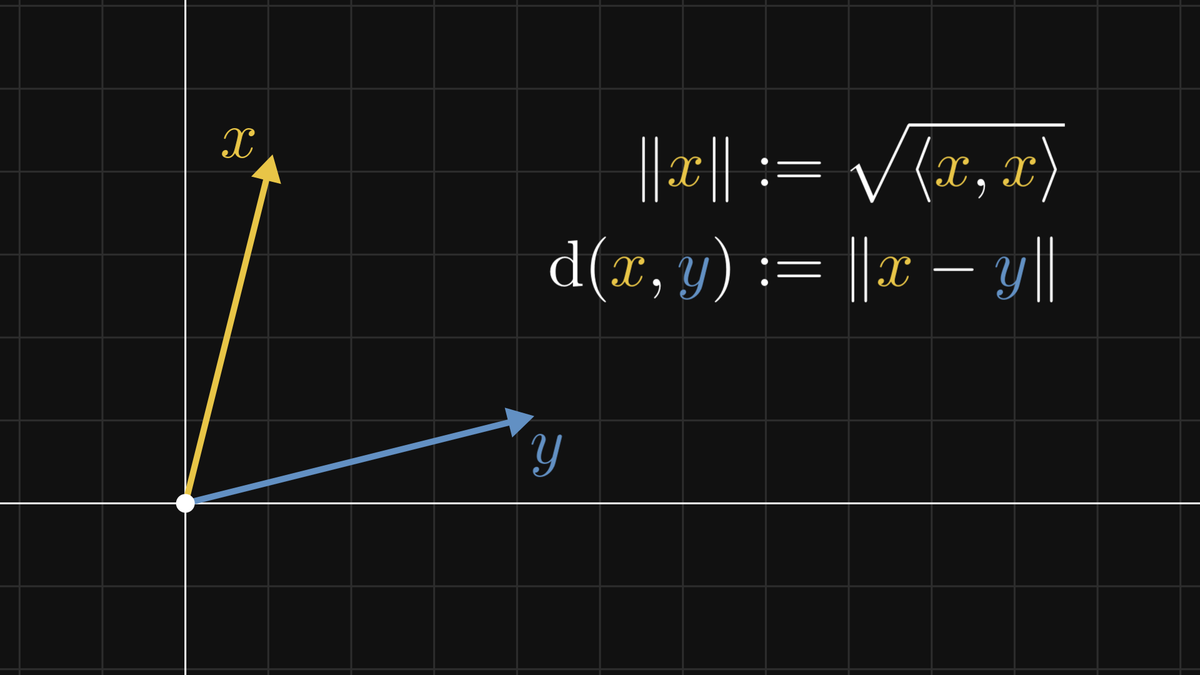

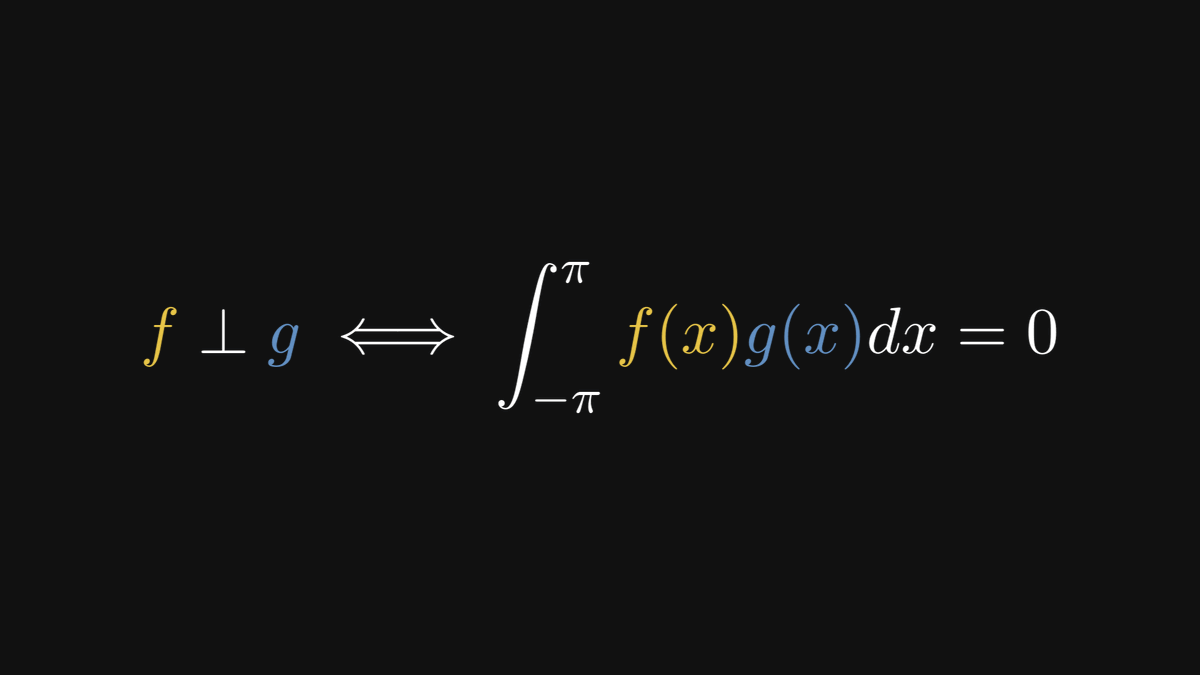

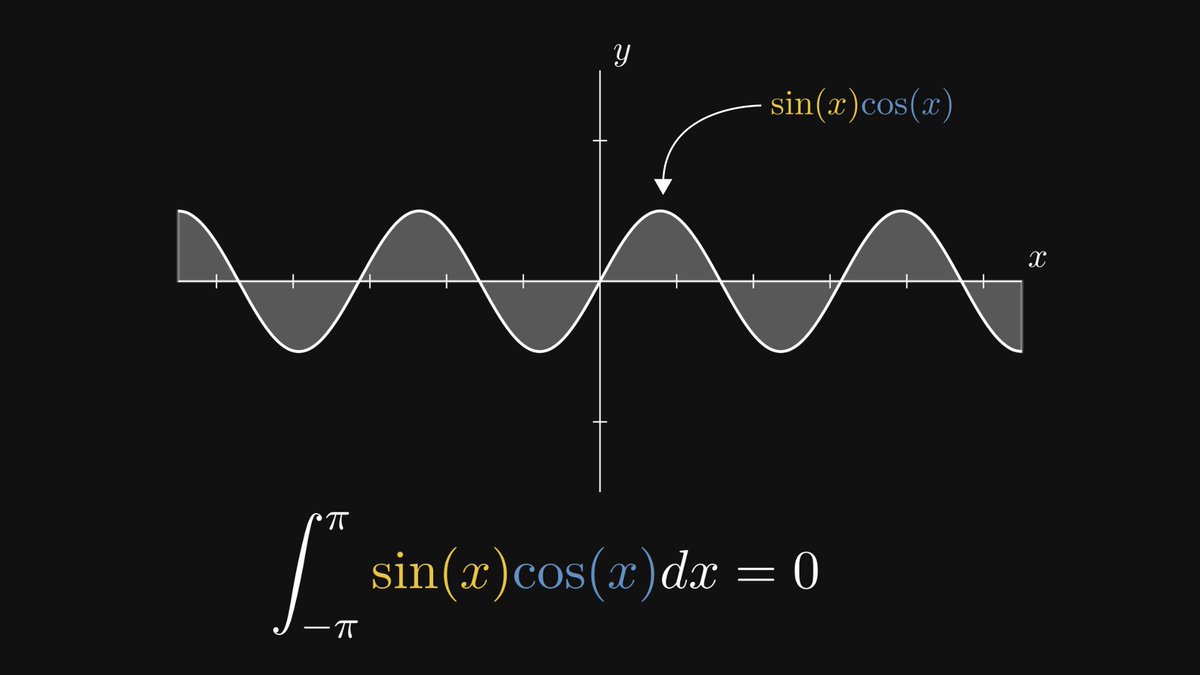

2. show what angles really are,

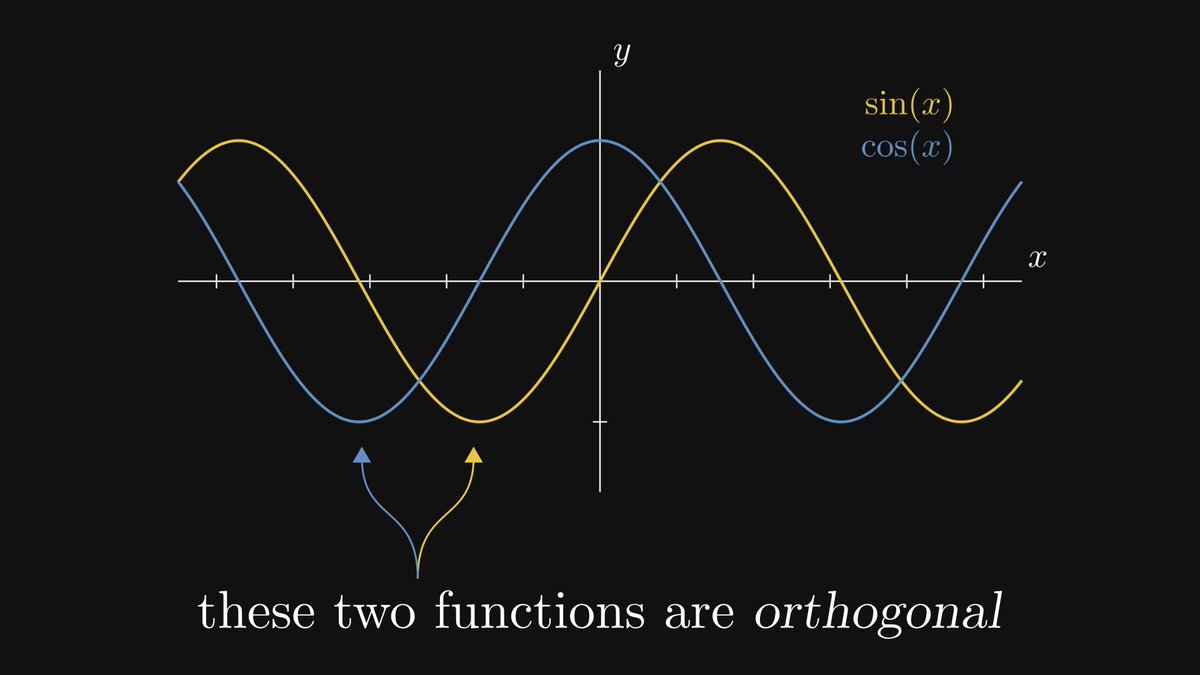

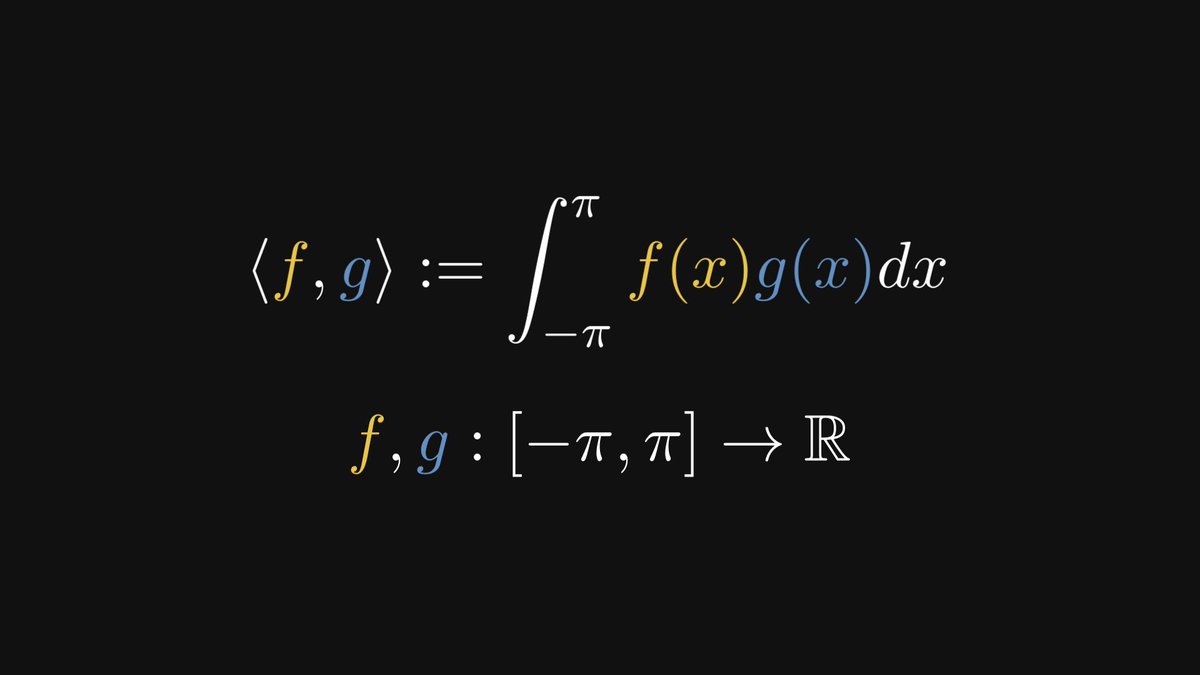

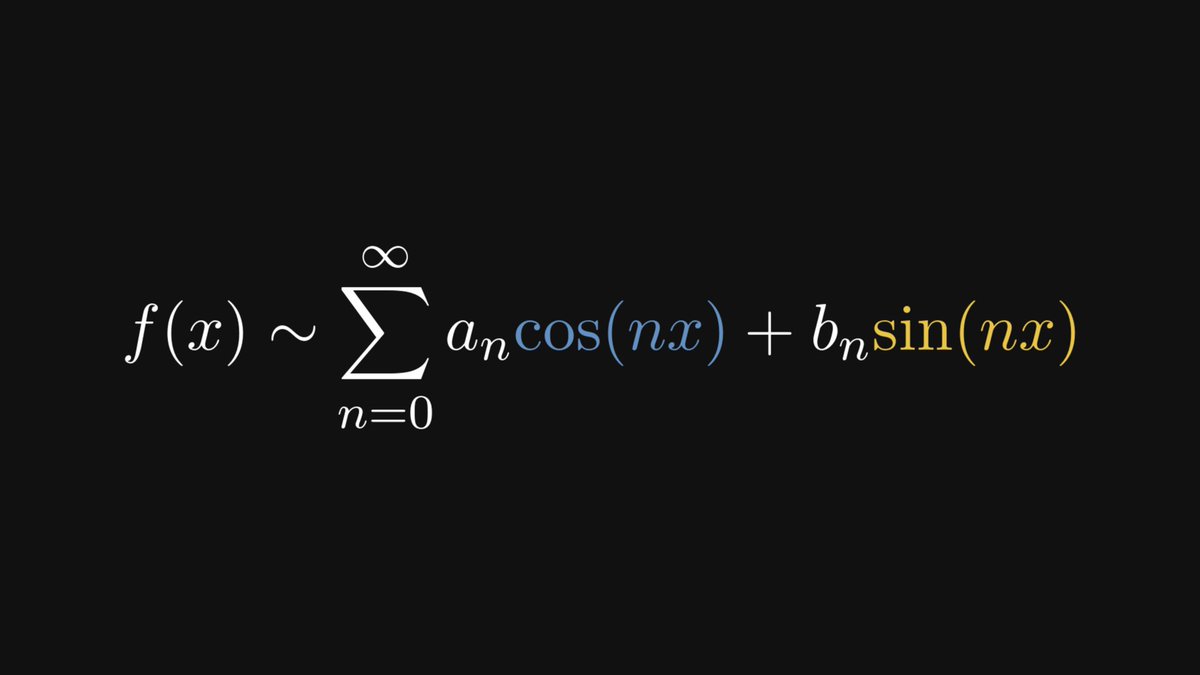

3. and see what functions have to do with all this.

Here we go!

1. generalize the concept of a vector,

2. show what angles really are,

3. and see what functions have to do with all this.

Here we go!

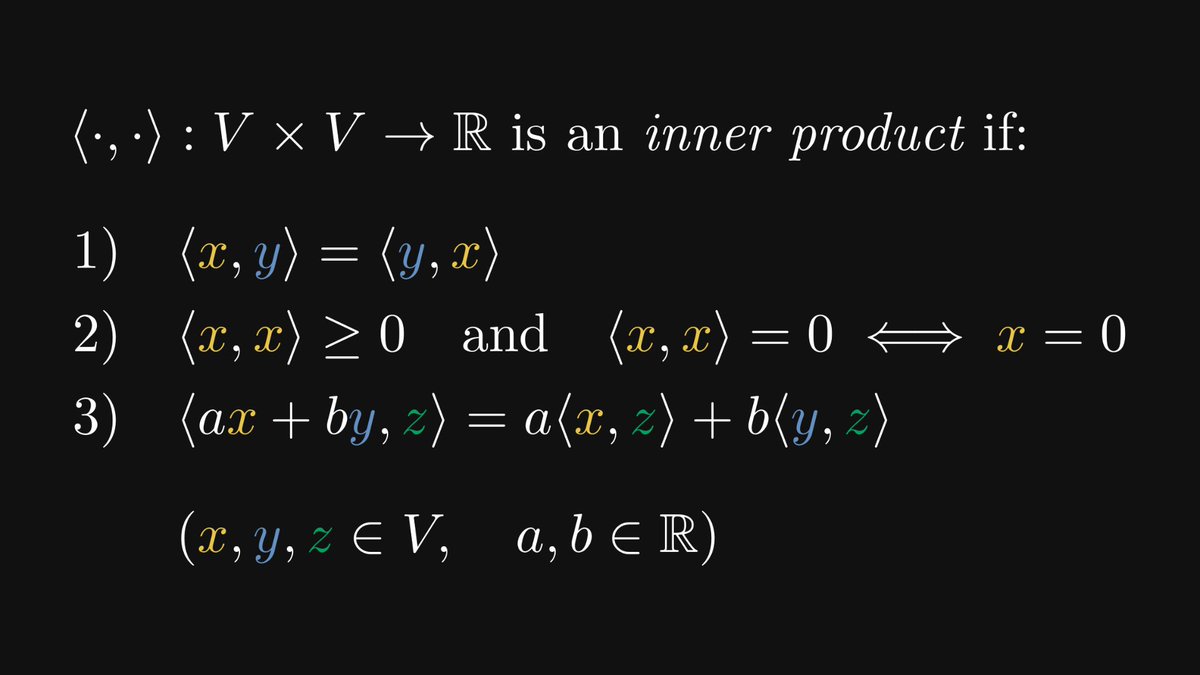

What makes a vector? Two things: vector addition and scalar multiplication. We can take the core properties of these operations and turn them into a definition!

This is the process of abstraction.

This is the process of abstraction.

This thread is part of the latest issue of The Palindrome.

In the full post, I go into the details of

- the process of abstraction,

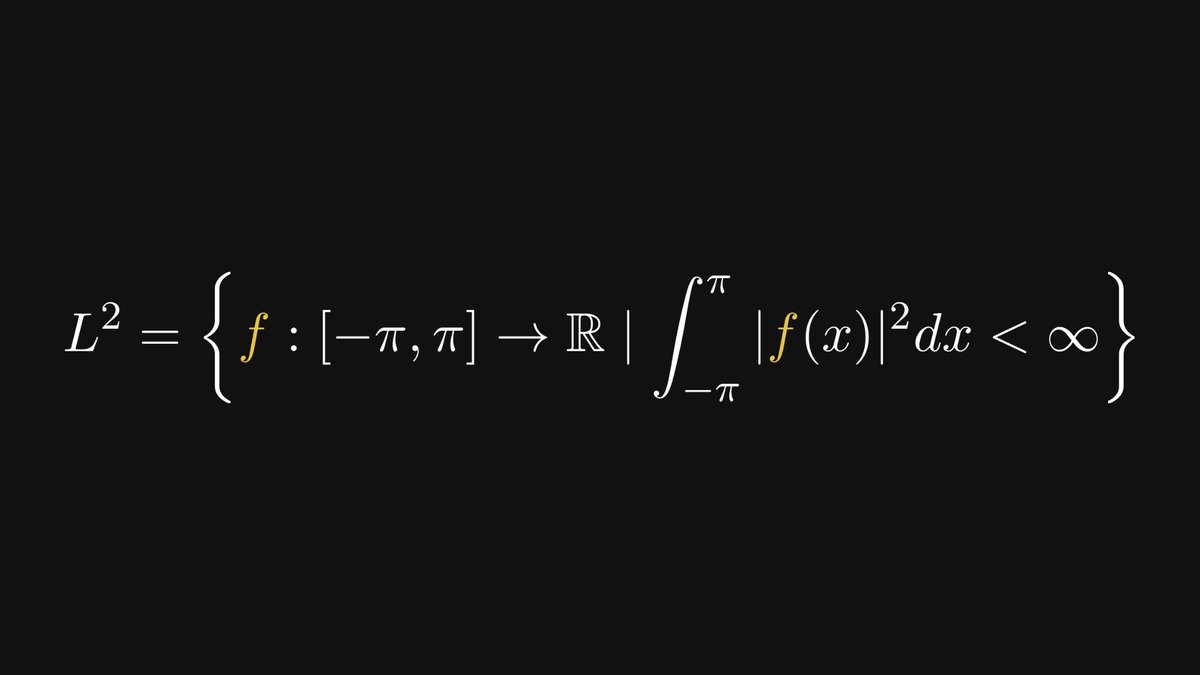

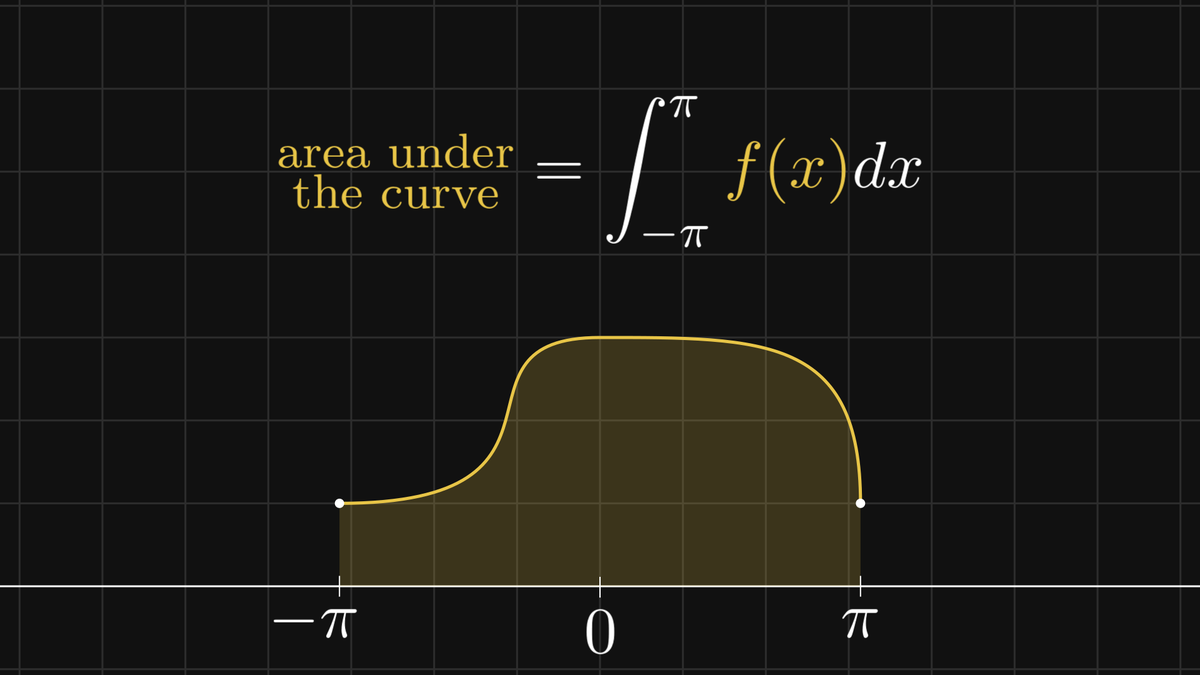

- why is the L² inner product a natural idea,

and much more!

thepalindrome.substack.com

In the full post, I go into the details of

- the process of abstraction,

- why is the L² inner product a natural idea,

and much more!

thepalindrome.substack.com

If you have enjoyed this thread, share it with your friends and follow me!

I regularly post deep-dive explanations about big ideas and complex concepts.

Understanding mathematics will make you a smarter person, and I want to help you with that.

I regularly post deep-dive explanations about big ideas and complex concepts.

Understanding mathematics will make you a smarter person, and I want to help you with that.

Loading suggestions...