This might not be going where you think.

Places around the world used to look more different. Now, with a seemingly global, modern style, they look more and more similar. Why?

The place to start is with another question: where did traditional architecture come from?

Places around the world used to look more different. Now, with a seemingly global, modern style, they look more and more similar. Why?

The place to start is with another question: where did traditional architecture come from?

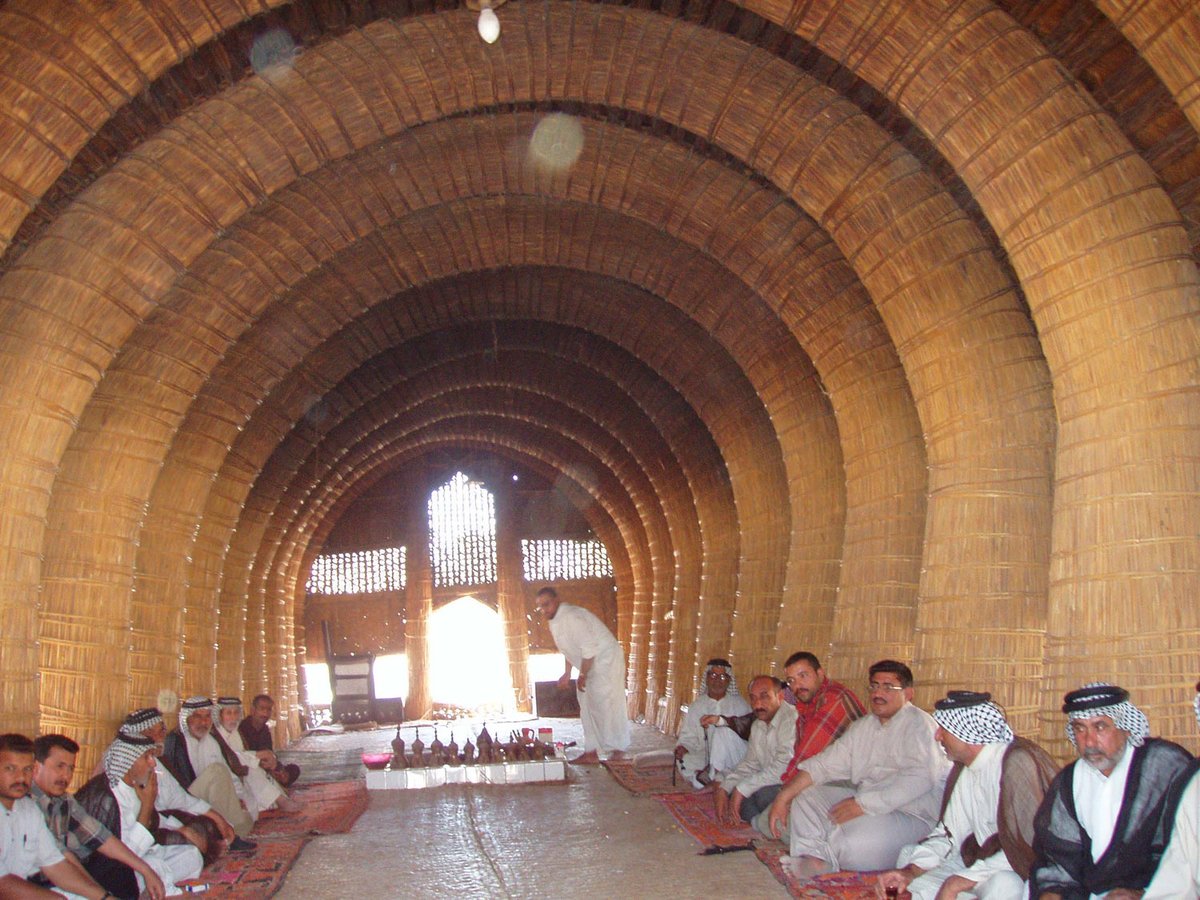

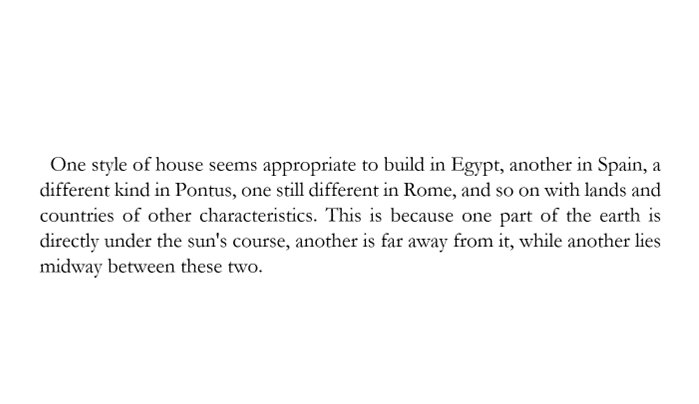

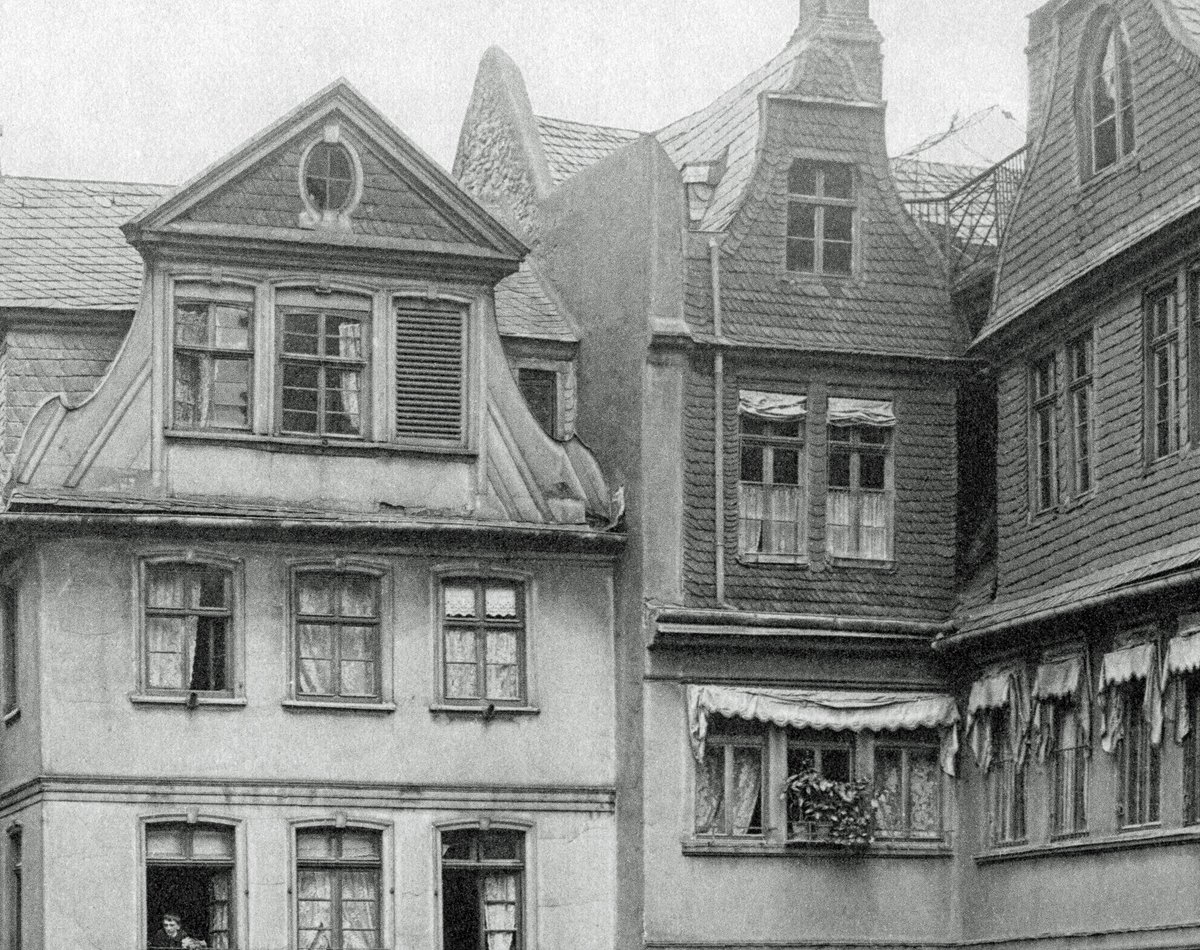

Each country and region in the world once had distinctive architecture first and foremost because of their geology, ecology, and climate.

Factors with which culture then interacted to create styles that were more consciously specific to a group, religion, or culture.

Factors with which culture then interacted to create styles that were more consciously specific to a group, religion, or culture.

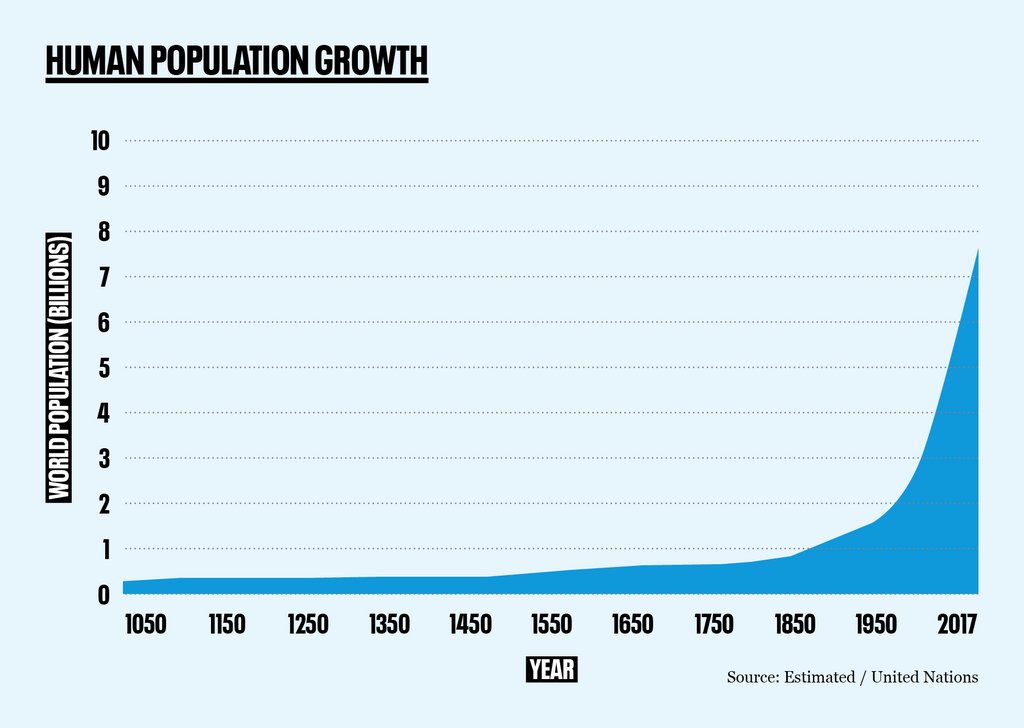

The increasingly global economy and improvements in transport have long since removed the need to rely on local materials.

In many places it has instead become cheaper and easier to ship in materials, natural or synthetic, than find or make them locally.

In many places it has instead become cheaper and easier to ship in materials, natural or synthetic, than find or make them locally.

Older architectural styles, especially the vernacular, are in some ways ill-suited to the demands of the modern world.

Their very reliance on local materials and craftspeople require a socio-economic infrastructure which simply doesn't exist anymore.

That's one view, anyway.

Their very reliance on local materials and craftspeople require a socio-economic infrastructure which simply doesn't exist anymore.

That's one view, anyway.

And so the real question (or two) turns out to be: is traditional architecture - whatever that means for whichever part of the world - still important? And, if so, is it still possible?

In many places it continues to exist and in others it is making a comeback.

In many places it continues to exist and in others it is making a comeback.

Architecture is always a choice, one which is both restricted and expanded by technological, economic, political, and socio-cultural factors.

Traditional architecture around the world came from specific contexts which have changed.

Does it have a place in the modern world?

Traditional architecture around the world came from specific contexts which have changed.

Does it have a place in the modern world?

I also write about architecture in my free newsletter, Areopagus.

It features seven topics every Friday, including history, art, and music.

To make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, consider joining 50k+ other readers here:

culturaltutor.com

It features seven topics every Friday, including history, art, and music.

To make your week a little more interesting, useful, and beautiful, consider joining 50k+ other readers here:

culturaltutor.com

Loading suggestions...