Up to 65% of the nitrogen (N) applied on coffee farms is lost to leaching or volatilization.

The N that leaches through the soil profile makes its way into groundwater and waterways, contaminating the farmers' water sources along with surrounding communities.

The N that leaches through the soil profile makes its way into groundwater and waterways, contaminating the farmers' water sources along with surrounding communities.

The volatilization of synthetic N contributes nitrous oxide to the atmosphere.

Nitrous oxide has an atmospheric warming potential 265x greater than CO2.

Coffee-growing regions are already experiencing climate instability.

Who knew coffee was contributing to its own demise?

Nitrous oxide has an atmospheric warming potential 265x greater than CO2.

Coffee-growing regions are already experiencing climate instability.

Who knew coffee was contributing to its own demise?

One unique characteristic of coffee farming is the lack of irrigation infrastructure on most farms.

Coffee trees rely on predictable rainfall cycles and water stored in the soil to produce a crop of cherries each year.

Coffee trees rely on predictable rainfall cycles and water stored in the soil to produce a crop of cherries each year.

Between rain events and during the dry season, coffee trees can access the water stored in the soil through capillary action; the same way water moves up through a straw resting in a glass.

Synthetic N fertilizers were once thought to contribute to, or at least maintain soil organic matter (SOM).

However, several recent long-term studies show that these fertilizers caused a net decline in SOM even with massive additions of residues (organic matter) to the soil.

However, several recent long-term studies show that these fertilizers caused a net decline in SOM even with massive additions of residues (organic matter) to the soil.

Prolonged use of synthetic N drastically reduces the water holding capacity on coffee farms, leaving them parched and lacking resilience in the face of drought and extreme weather.

But that's not all...

But that's not all...

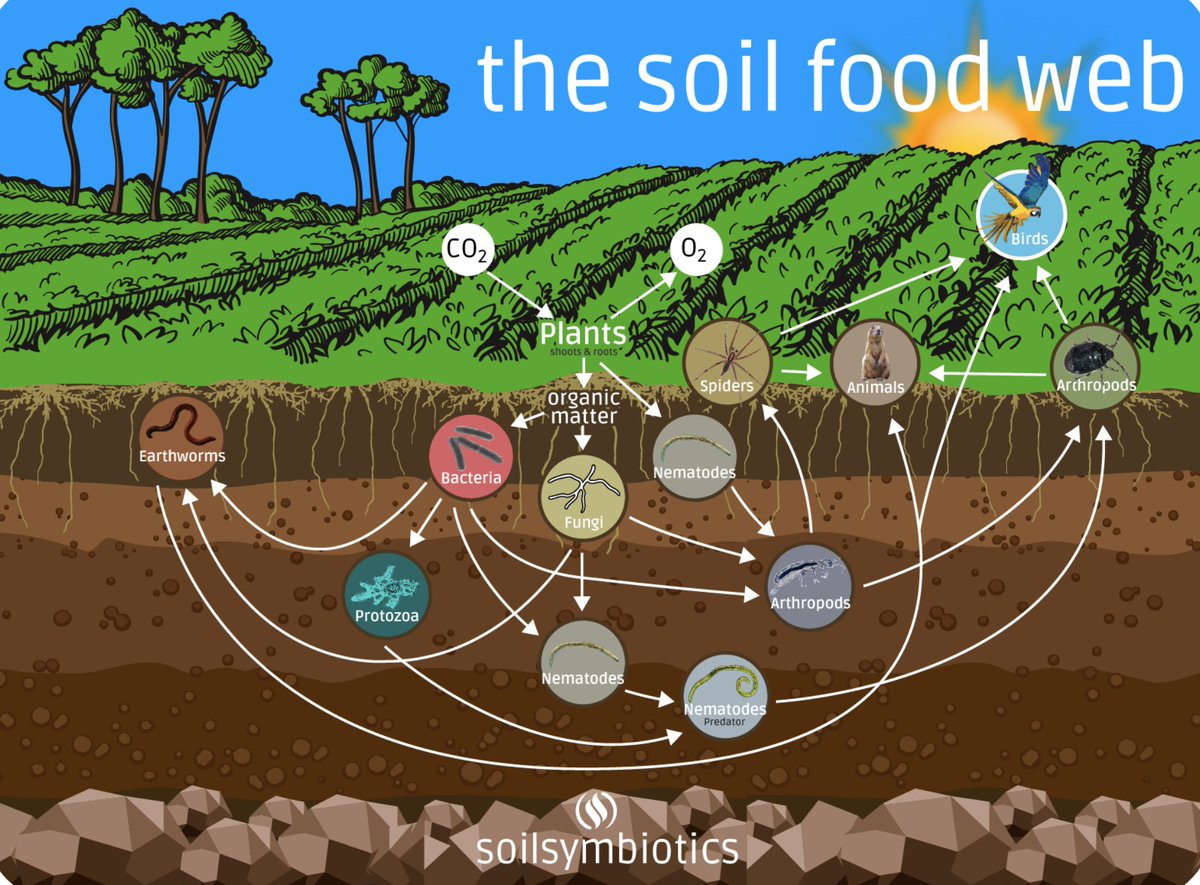

The key to creating optimal nutritional conditions is assuring the availability of a broad spectrum of minerals for plant uptake, mediated by a thriving web of soil microorganisms.

The exorbitant rates of synthetic nitrogen used on coffee farms impede the uptake of essential nutrients like calcium, potassium, boron, copper, and several other key mineral nutrients related to coffee quality.

Elevated N levels in plant sap decrease the levels of phenolic compounds and other secondary metabolites responsible for creating each coffee’s unique flavor signature

These same flavor-giving compounds impart immune-boosting qualities to plants that ward off disease and pests

These same flavor-giving compounds impart immune-boosting qualities to plants that ward off disease and pests

It's important to note that nitrogen is an essential plant nutrient, and in no way am I dismissing this fact.

It becomes problematic when applied in the wrong form and at the wrong rate, like in the case of coffee production. The adverse effects outweigh any benefits.

It becomes problematic when applied in the wrong form and at the wrong rate, like in the case of coffee production. The adverse effects outweigh any benefits.

Unlike other agricultural commodities, coffee thrives in the understory of other trees and can be interplanted with countless other crops.

This gives farmers the unique opportunity to generate multiple revenue streams and generate an abundance of on-farm fertility.

This gives farmers the unique opportunity to generate multiple revenue streams and generate an abundance of on-farm fertility.

Through this process, common nitrogen-fixing shade trees can contribute 60-350 kg/ha of nitrogen from leaf litter and residues and another 30-60 kg/ha of N from symbiotic fixation in the rhizosphere. (Source – Coffee: Growing, Processing, Sustainable Production, 2nd Edition)

This can exceed the recommended rates of synthetic nitrogen, yet in a more plant-available form that doesn’t leach or volatilize and comes with the added benefit of significantly increased soil organic matter, enhanced nutrient cycling, and improved water holding capacity

In order to fully benefit from the wonder of biological nitrogen fixation, farmers need to understand the interplay between soil minerals, the physical structure of the soil, and beneficial soil microorganisms.

A coffee farm that I've worked with for several years recently completed a transition away from synthetic N inputs.

After decades of applying an average of 200 kgs per ha, the farm now applies zero synthetic N.

After decades of applying an average of 200 kgs per ha, the farm now applies zero synthetic N.

Nitrogen is supplied by a small amount of compost, bio-stimulants, symbiotic N fixation, specialized diazotrophic inoculants, and a functional soil food web.

This approach takes up a tiny fraction of the farm's former synthetic nitrogen budget.

This approach takes up a tiny fraction of the farm's former synthetic nitrogen budget.

Coffee leaf rust was a major issue on this farm. Infection rates were historically between 20 - 40% with the use of fungicides.

Now infection rates are below 5% without the use of fungicides.

Now infection rates are below 5% without the use of fungicides.

This is only the start of what's possible when we take an integrated, principle-based approach to growing coffee.

It all starts with questioning common assumptions and standard practices.

It all starts with questioning common assumptions and standard practices.

Loading suggestions...