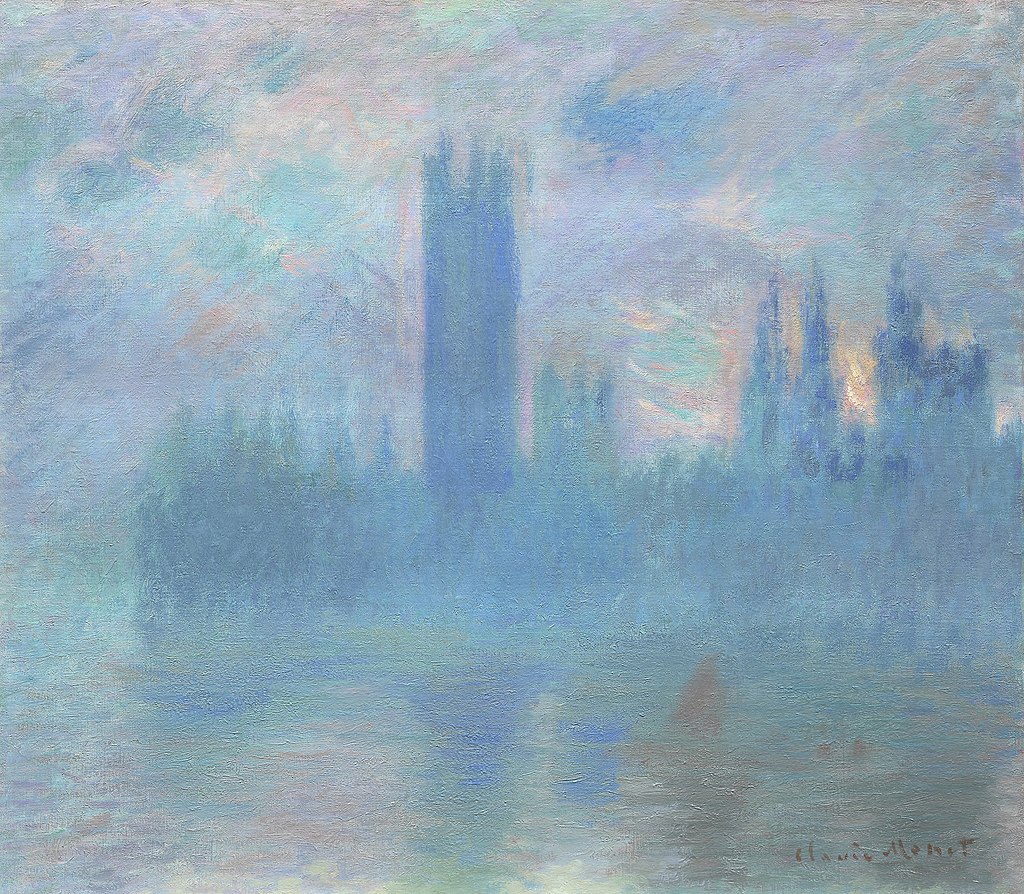

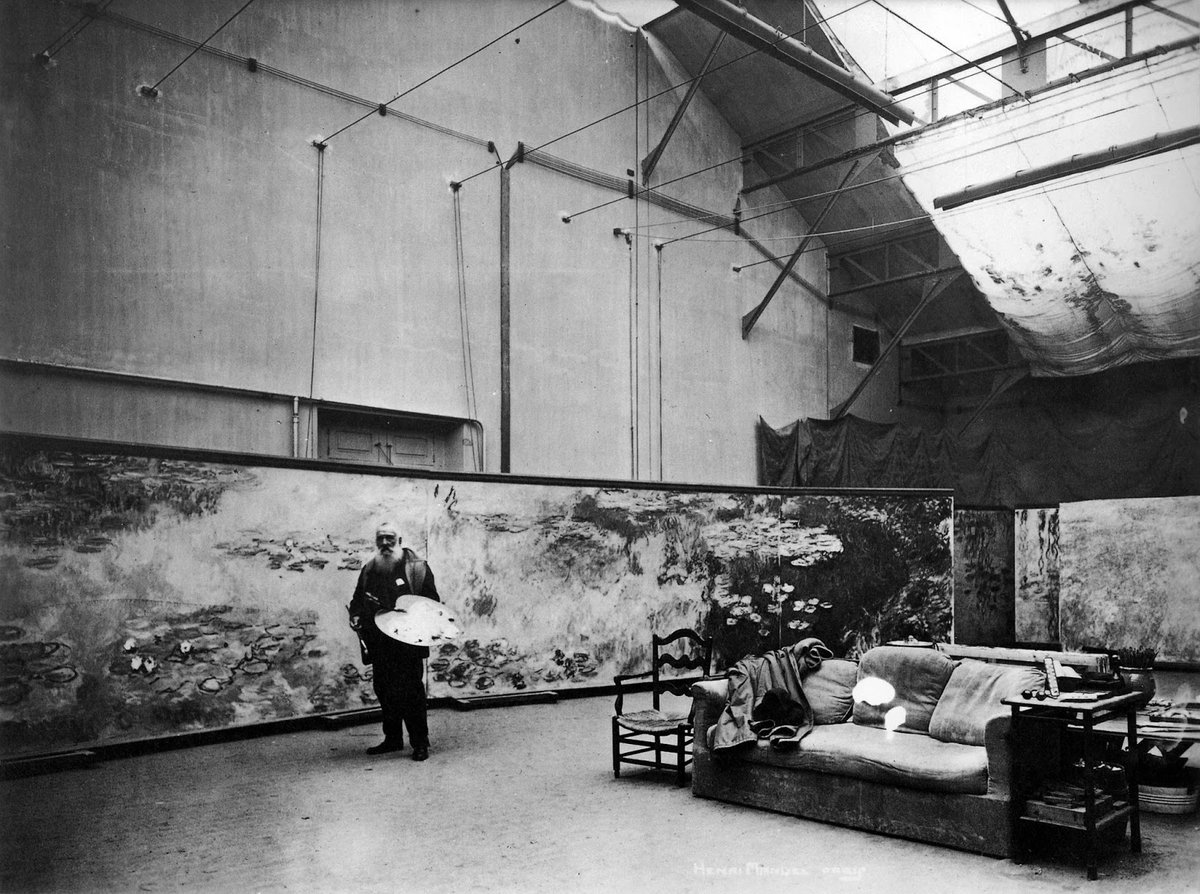

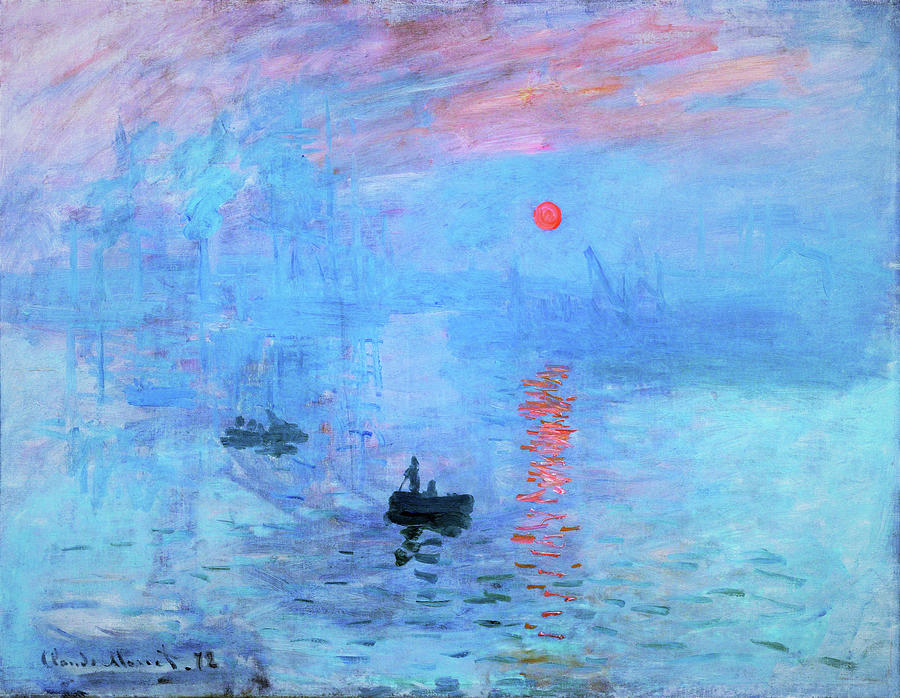

Claude Monet took this idea further than any other member of the Impressionist movement.

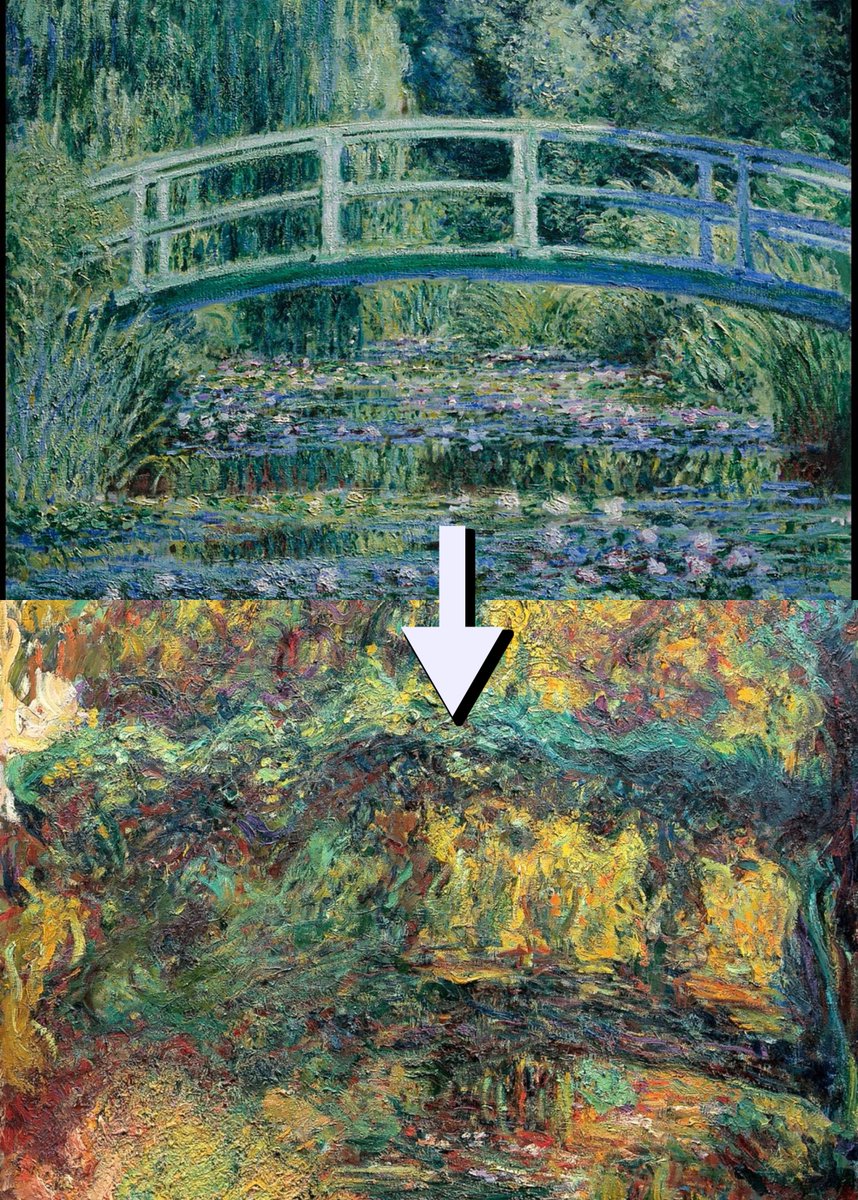

He saw the importance of light and its impact on colour in how we perceive the world around us. The same object, scene, or person appeared differently depending on the time of day.

He saw the importance of light and its impact on colour in how we perceive the world around us. The same object, scene, or person appeared differently depending on the time of day.

Loading suggestions...