Long long time back I used to "mod" kernels on @xdadevelopers (which basically means you do stuff like recompile the Linux kernel from source, add more higher clock multiples, and overclock your phone etc).

One thing I discovered that absolutely fascinated me?

"handoff"

One thing I discovered that absolutely fascinated me?

"handoff"

So you're sitting in a car or a train, and you are on a phone call, maybe with your significant other, whispering silly nothings to each other for over a couple of hours.

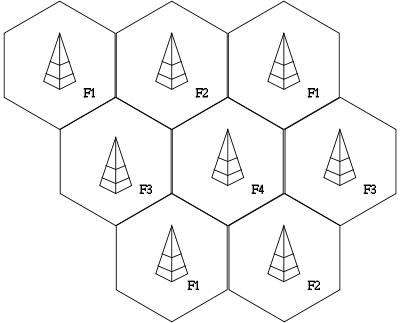

Guess what you might have traversed a dozen "cells" during that time. You know the "cell" of cellphone.

Guess what you might have traversed a dozen "cells" during that time. You know the "cell" of cellphone.

Now if you are travelling across 50km, you have probably traversed 20 cells or so easily.

And if during this entire duration your call didn't "drop". It means your phone seamlessly bounced from one tower to another, without you noticing.

And if during this entire duration your call didn't "drop". It means your phone seamlessly bounced from one tower to another, without you noticing.

While there's a lot of heavy lifting that the network itself has to do - on the phone's side also there's a bit of work.

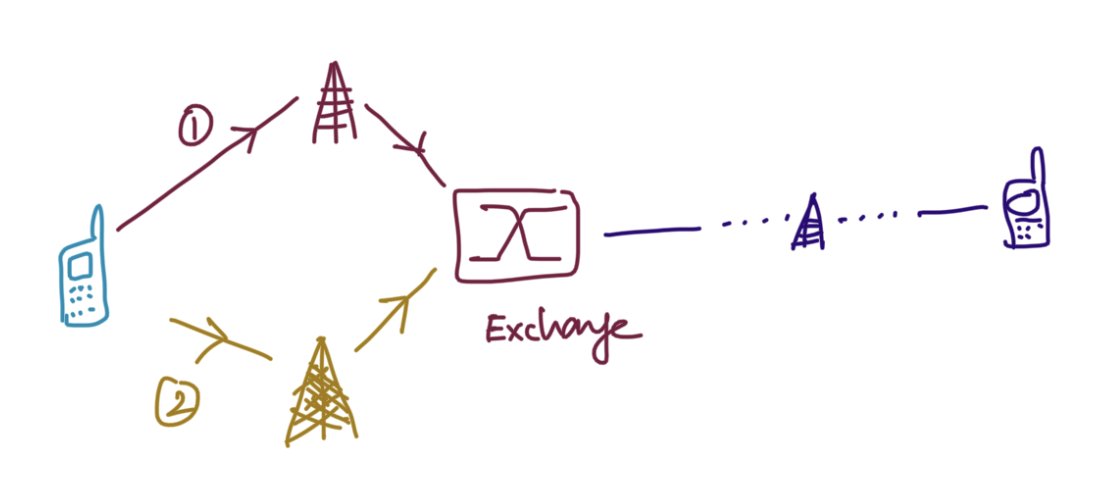

Depending on the type of "handoff" that is going to happen - a "hard" handoff is when connection with one tower must break before making with a new one.

Depending on the type of "handoff" that is going to happen - a "hard" handoff is when connection with one tower must break before making with a new one.

A "soft" handover is when the new connection is made, there is a bit of overlap, and then the old one is dropped.

If you are on 2G (GSM) networks, which well a lot of people were back in 2012-13 when I was tinkering with Android kernel codes, the handover is hard. WCDMA is soft

If you are on 2G (GSM) networks, which well a lot of people were back in 2012-13 when I was tinkering with Android kernel codes, the handover is hard. WCDMA is soft

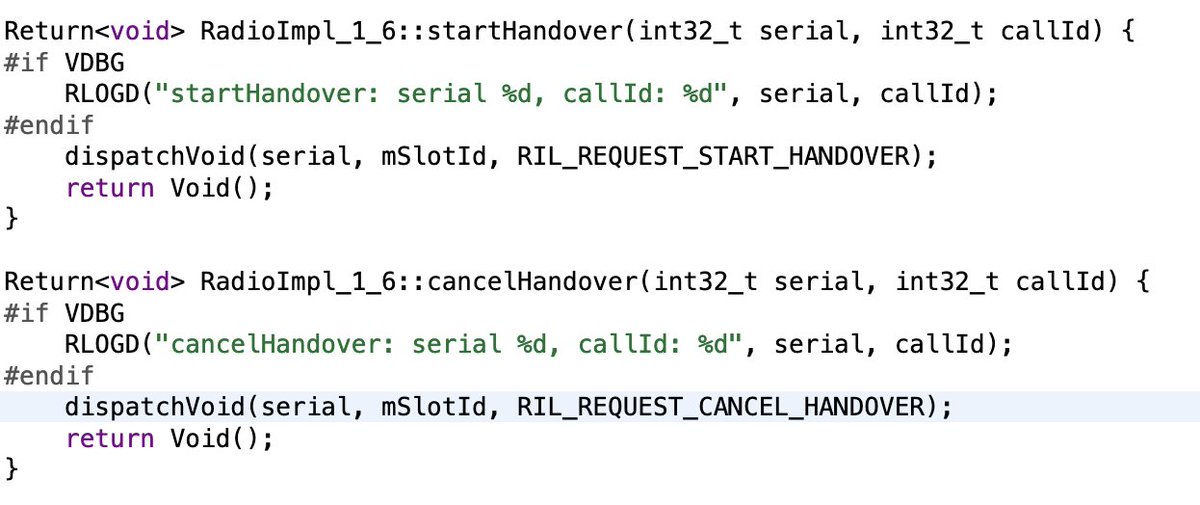

On Android phones there is something called the "RIL" or the "radio interface layer". Which has nothing to do with FM Radio but all to with the GSM/WCDMA/UMTS/LTE radio.

In the world of modded kernels, and modded aftermarket Android firmware (a la CyanogenMod)...

In the world of modded kernels, and modded aftermarket Android firmware (a la CyanogenMod)...

... the "RIL" is usually never touched.

The reason being, that there are a lot of companies with more lawyers than engineers involved in making the secret juice that goes into these 2G, 3G, 4G technologies. So the "RIL" is usually always in a black box radio.bin

The reason being, that there are a lot of companies with more lawyers than engineers involved in making the secret juice that goes into these 2G, 3G, 4G technologies. So the "RIL" is usually always in a black box radio.bin

But if you want to self-compile a newer version of Linux kernel or Android OS for your phone, than the one that shipped, you might have to understand (and sorta reverse engineer) the surface of RIL so that the OS/Kernel can at least talk to that black box.

My brush with handover happened when on a certain modified kernel, that we released (we = me and some other kids trying to overclock phones 😅), a lot of users complained that calls seem to disconnect when travelling.

And obviously none of that made much sense because the reference RIL is more like a bunch of abstract classes and interface that Google makes and puts it off to people like Qualcomm and all who actually make cellullar radio chips to implement.

But nevertheless that led me down the rabbit hole of understanding what handoff or handover is, and how it works, and it was an absolute 🤯🤯🤯 season.

Soft handoffs are incredibly hard to actually do because of all the moving pieces involved.

Soft handoffs are incredibly hard to actually do because of all the moving pieces involved.

The phone connects to the next tower (called the target), while the call is still running on the previous (source) tower.

Phone <> cell tower, 2 parallell calls basically start at that point, while the telephone operator still sends data from source call to the other end.

Phone <> cell tower, 2 parallell calls basically start at that point, while the telephone operator still sends data from source call to the other end.

So yeah while working on info-systems, sometimes we pride over how many millions of connections our edge load balancer can handle etc, remember that these telcos (whose engineering isn't exactly we consider state-of-art) handle millions of such handovers every second as we speak

Loading suggestions...