As the British conquered more and more of India in the early 19th century, they came face to face with massive rock and pillar inscriptions with mysterious writings in a script no one could read. The locals told them the pillars were Bhimsen ki Lath - Bhima's walking sticks

Since no one knew the script, no one knew Ashoka as well. Ceylonese chronicles mentioned a great King of that name but he was believed to be a local of that island. Worse still, Buddhism's history in India was mostly unknown - the Bodh Gaya temple being a local Hindu shrine then

When Prinsep received copies of inscriptions from the Kotla and Ridge pillars in Delhi and from Sarnath and North Bihar, he had two options - he could either go at it statistically identifying patterns and guessing which letter appeared how often or he could trace its descendants

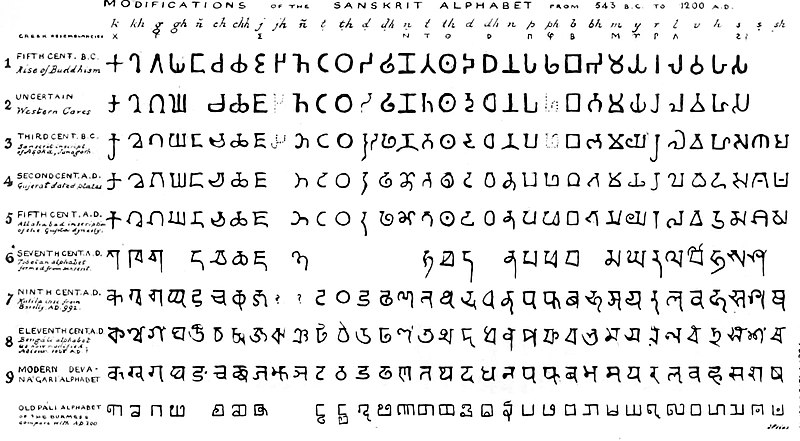

The latter wasnt something new. Champollion had cracked the Egyptian hieroglyphs by assuming the language hadn't disappeared but changed into the live language of Coptic. Prinsep believed that not only the language but also the script had modified into present Devanagari!

You can see the meticulous work that Prinsep put in. The क for eg is a straight descendant. Infact other Brahmi influenced alphabets have similar letters for it - like Tamil. Ashoka had spoken after 2 centuries and Prinsep was the first one to hear his voice.

Loading suggestions...