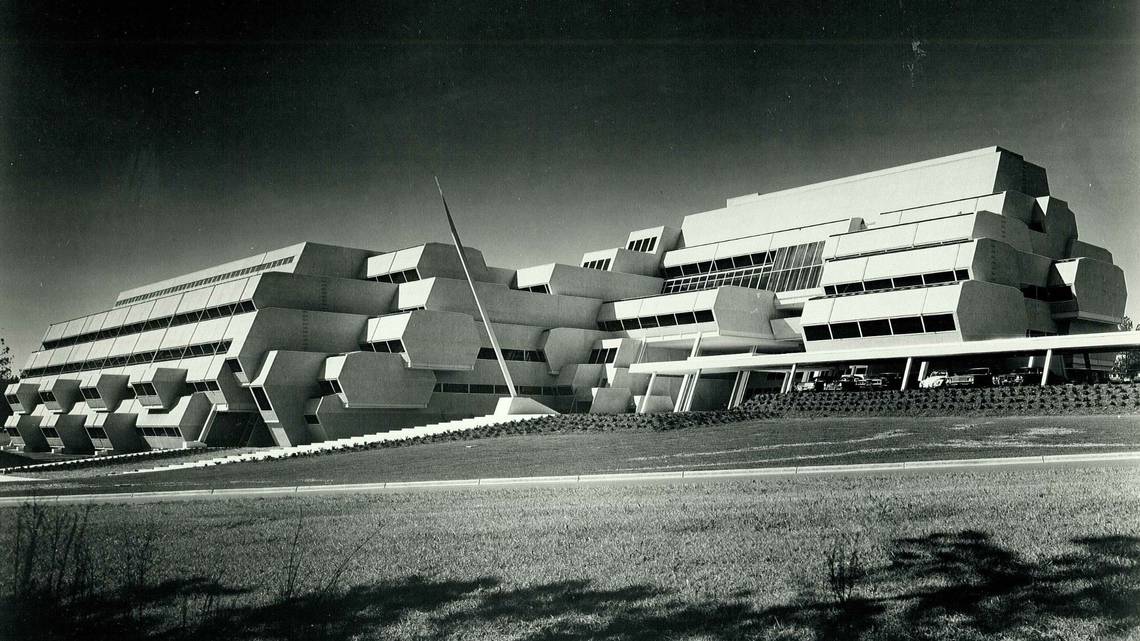

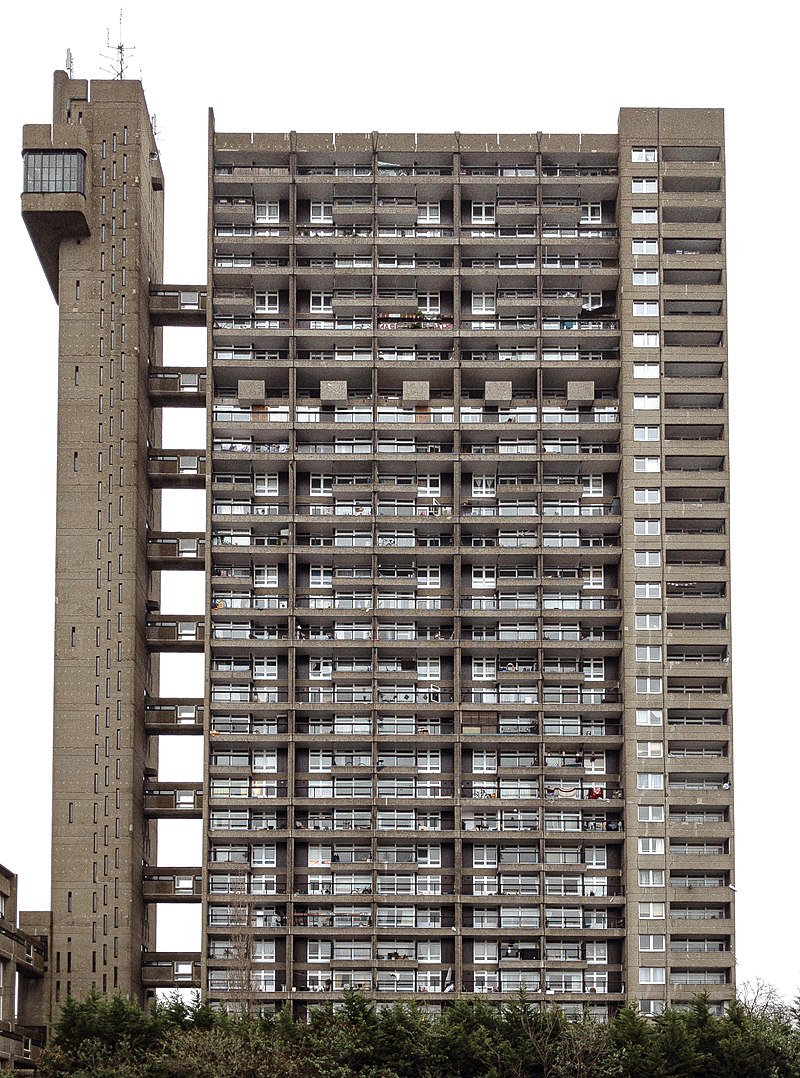

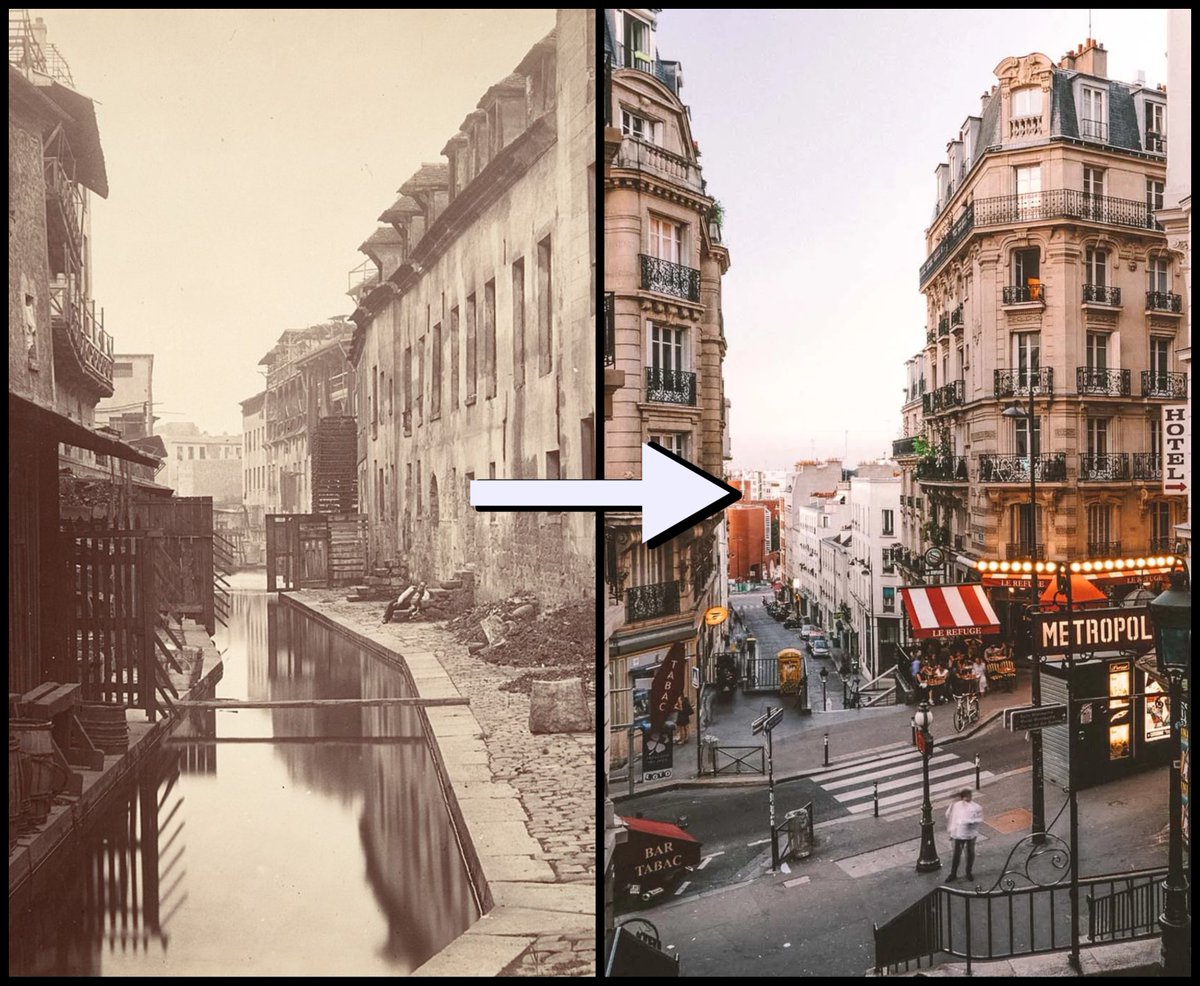

But Brutalism, whatever we think of its aesthetic merits, tells a central part of the story of the 20th century.

It emerged after the Second World War, when many parts of the world were in social, economic, political, and infrastructural turmoil.

This was a watershed moment.

It emerged after the Second World War, when many parts of the world were in social, economic, political, and infrastructural turmoil.

This was a watershed moment.

Loading suggestions...