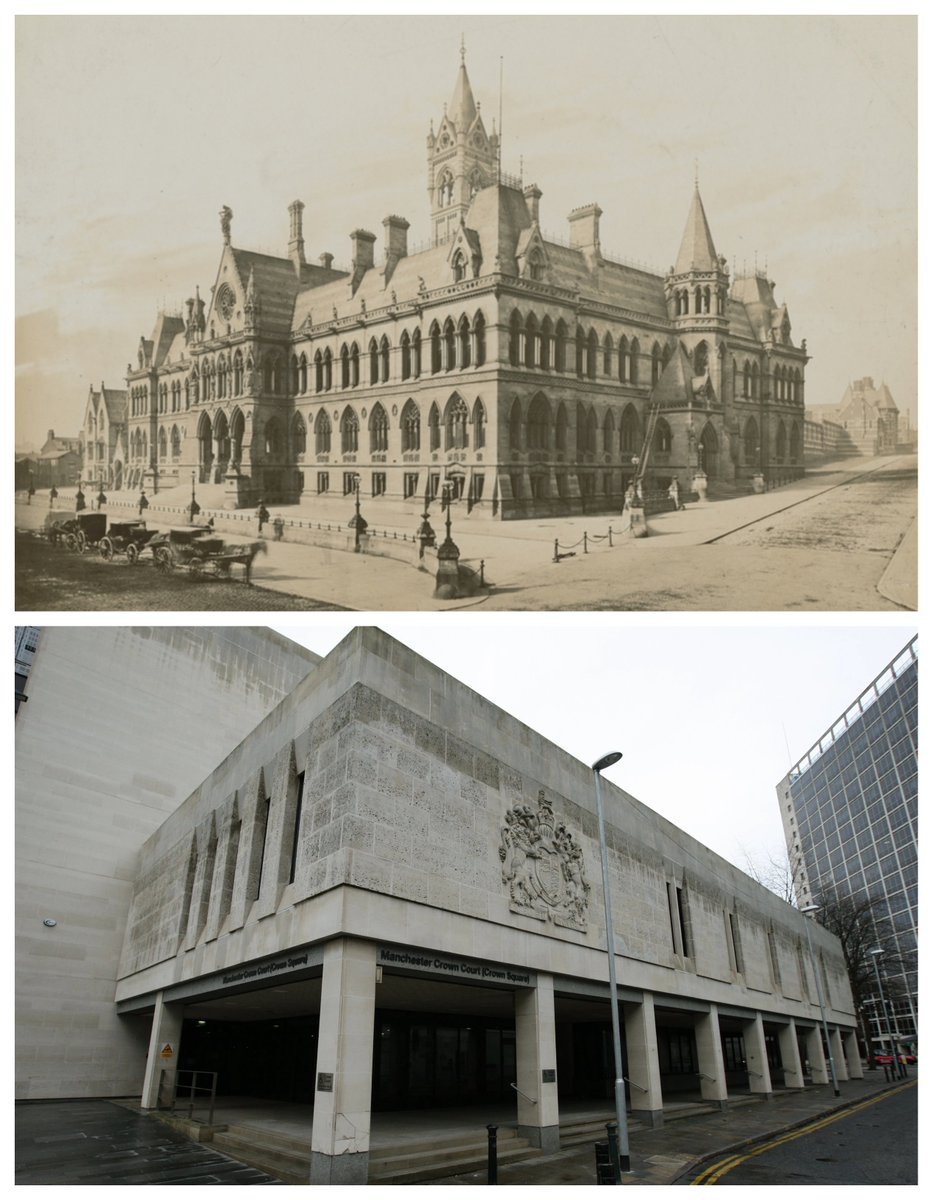

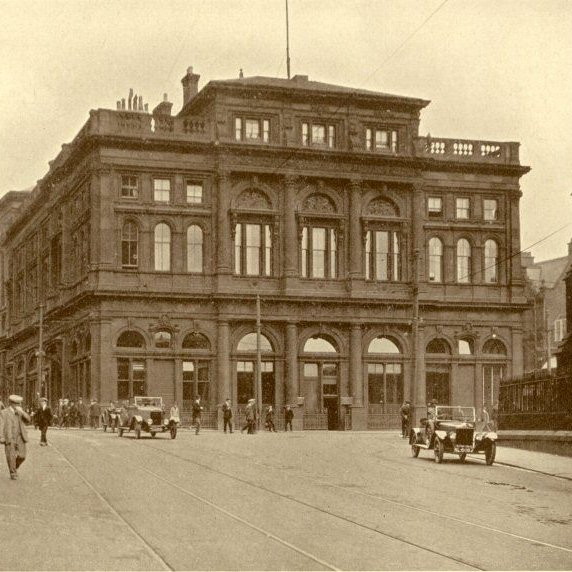

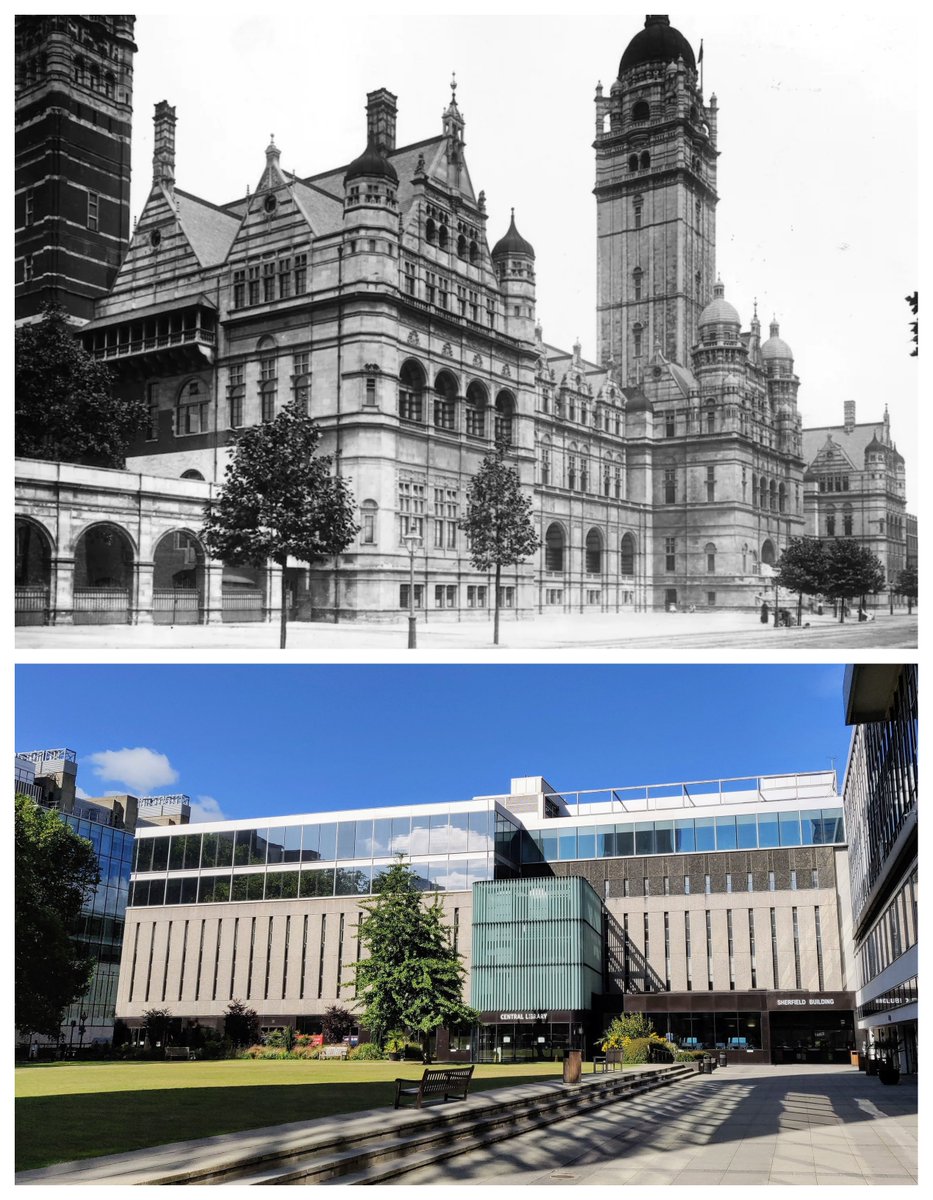

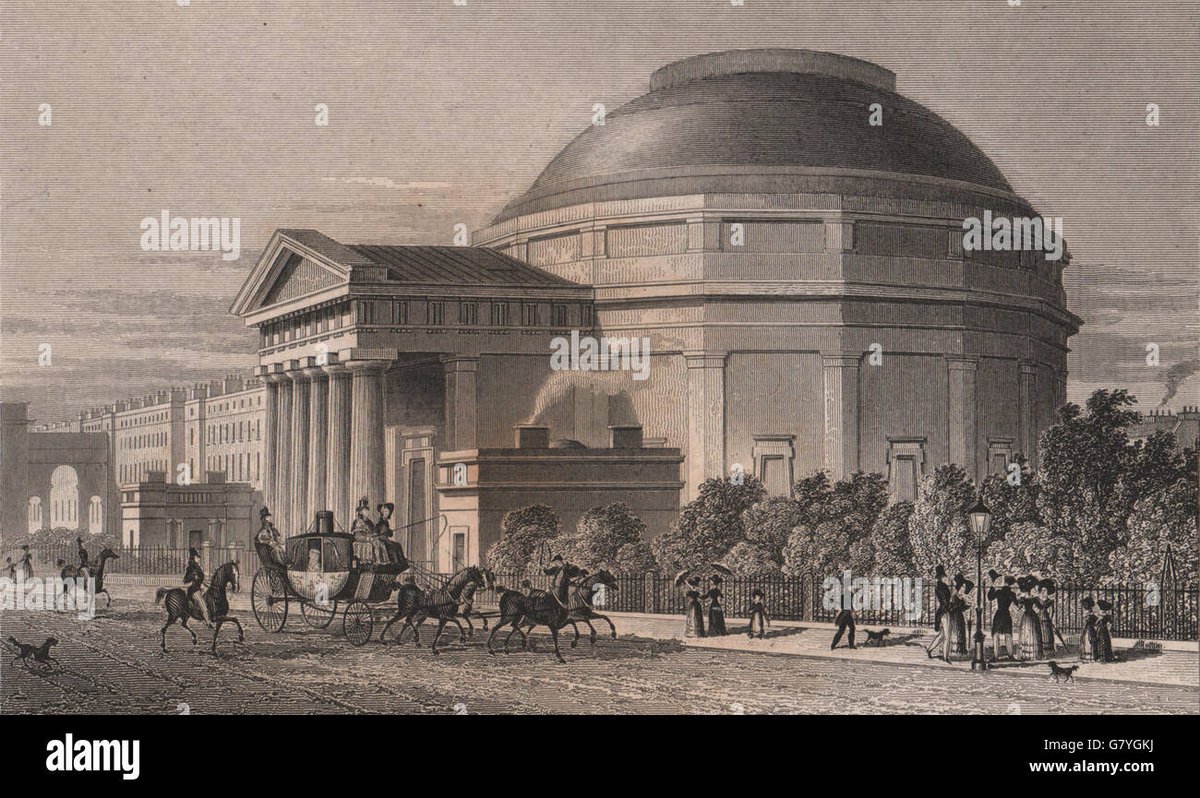

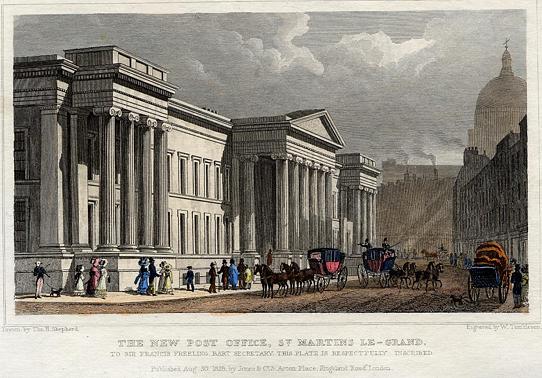

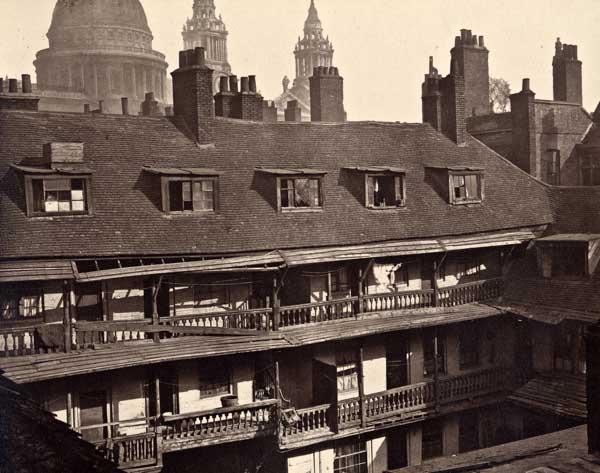

The decades that followed the Second World War saw a huge number of 19th and early 20th century buildings demolished all across Britain.

It seems like an architectural tragedy now - and many people at the time thought so, too - but in context it makes some sense.

It seems like an architectural tragedy now - and many people at the time thought so, too - but in context it makes some sense.

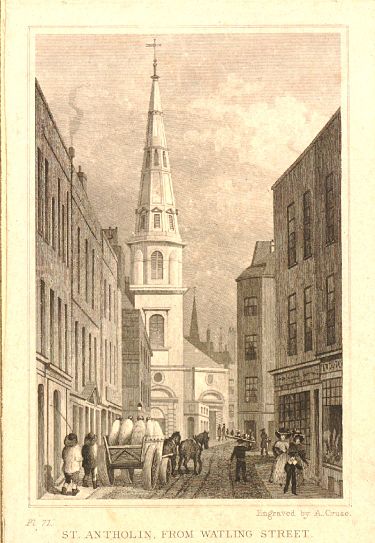

In the 1800s plenty of people lamented the rise of what they considered modern architecture alongside the demolition and replacement of even older buildings.

It happened again in the postwar decades and it's happening now with the destruction of Brutalism.

It happened again in the postwar decades and it's happening now with the destruction of Brutalism.

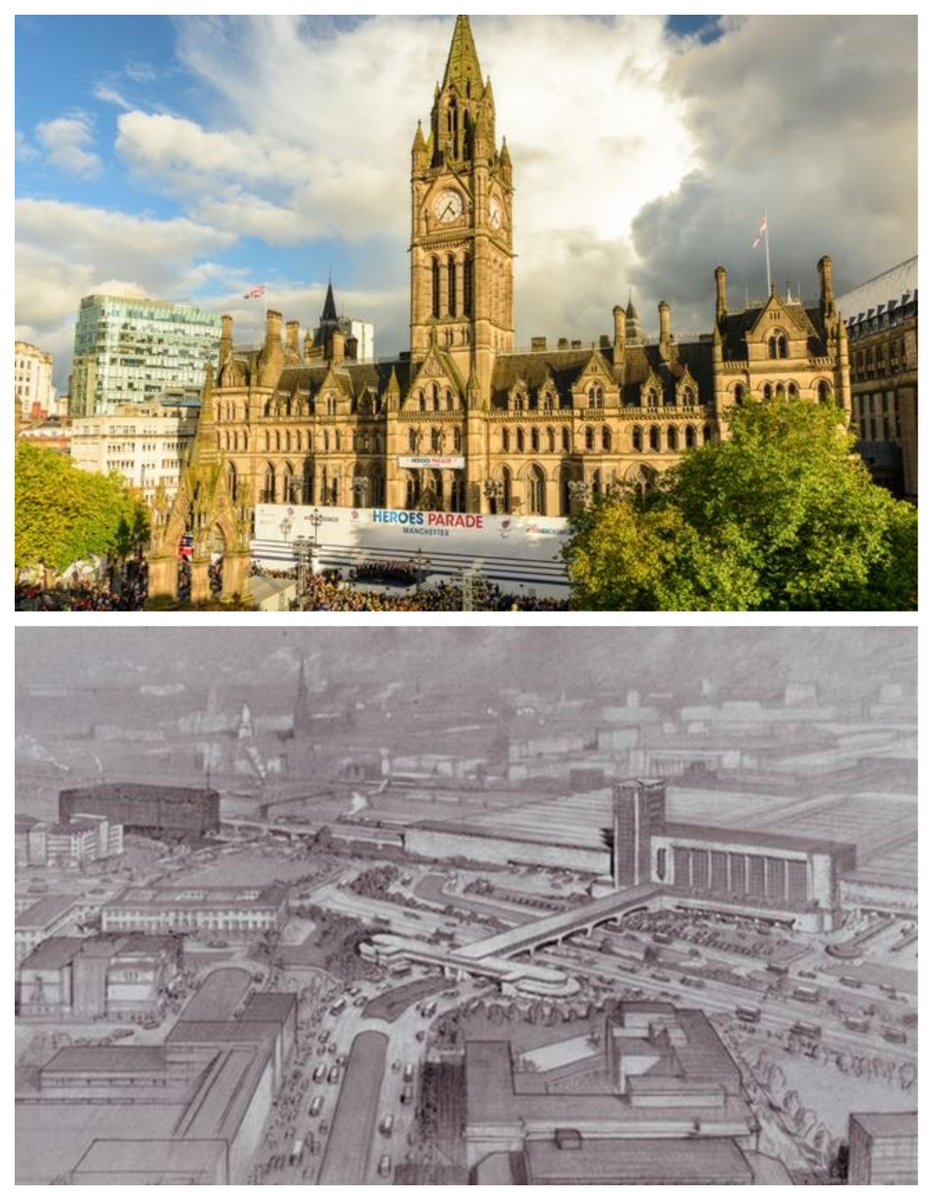

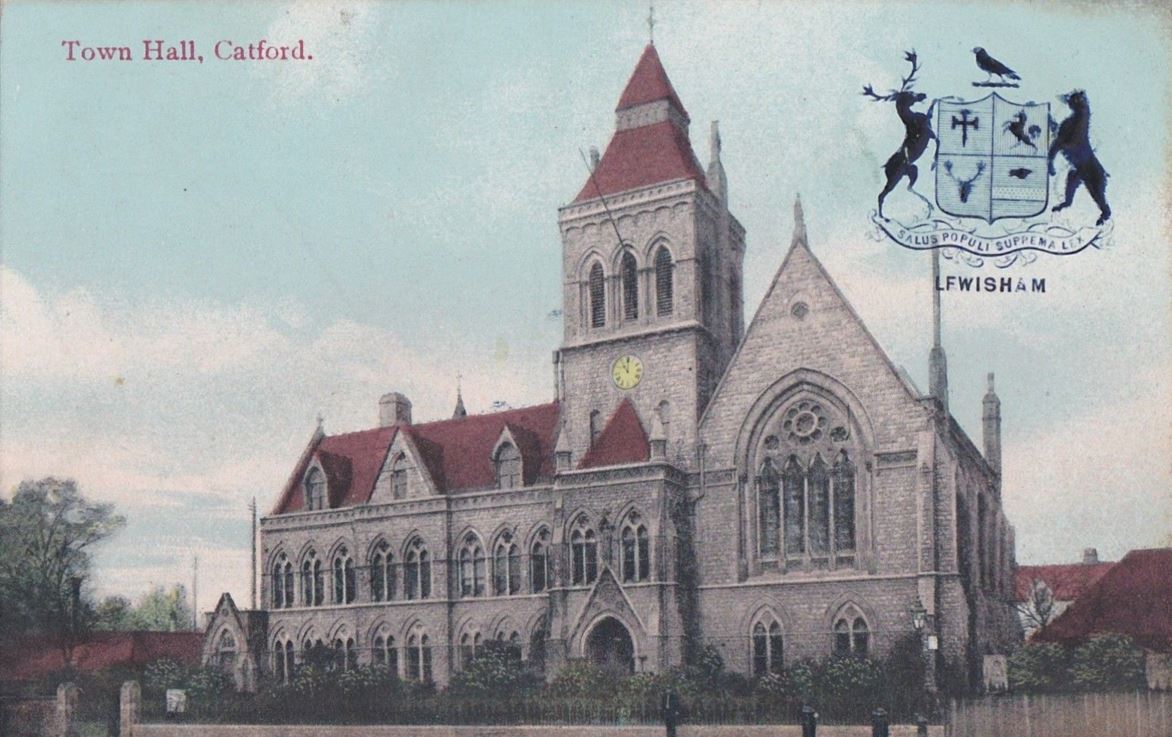

But all those Victorian demolitions in the 20th century strengthened the preservation movement in Britain.

Many buildings are now officially listed, thus protecting them from demolition or development, to ensure that the same thing won't happen again.

Many buildings are now officially listed, thus protecting them from demolition or development, to ensure that the same thing won't happen again.

Loading suggestions...