History

Politics

Religion

Islamic Studies

Islamic History

European History

Middle Eastern Politics

Cultural Commentary

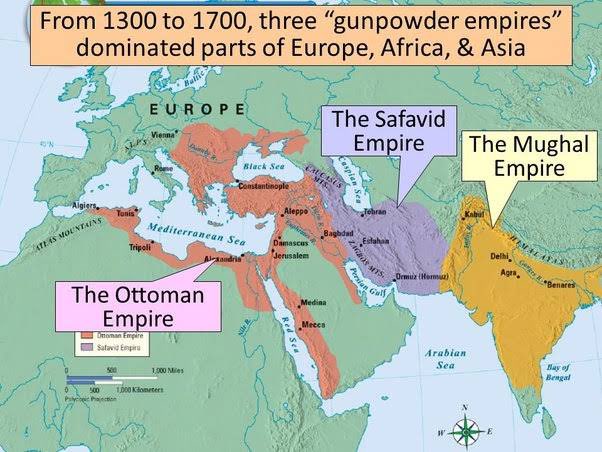

Once upon a time, there were two epicenters of Islamic power on Earth (3, but let’s stick to 2 now), the Ottomans in the Middle East and the Mughals in India.

Neither subservient to the other and neither willing to recognize the Caliphate of the other as authoritative of Islam.

Neither subservient to the other and neither willing to recognize the Caliphate of the other as authoritative of Islam.

This state of affairs remained in place for a good two-odd centuries before things took an abrupt turn toward the end of the 17th century.

Two events—the world continues to feel their repercussions to this day.

One of these just turned 323 years today.

Two events—the world continues to feel their repercussions to this day.

One of these just turned 323 years today.

The Ottomans weren’t just a political power but also ideological. Especially after the end of the Abbasids.

Unable to reconcile with their decline, the Muslim community needed a figurehead to help them make sense of all this and lead them to stability.

Unable to reconcile with their decline, the Muslim community needed a figurehead to help them make sense of all this and lead them to stability.

So in a space of one turbulent decade, the Islamic world had lost both its ideological nuclei.

And when such forces decline, others rush to fill in. That’s what happened here. Two men, both born in the same year during the “decade of decline” emerged as spiritual figureheads.

And when such forces decline, others rush to fill in. That’s what happened here. Two men, both born in the same year during the “decade of decline” emerged as spiritual figureheads.

Both saw reasons for the decline in the general departure from the Islamic core. Muslims had to be shepherded back to “the one true path” of Sharia.

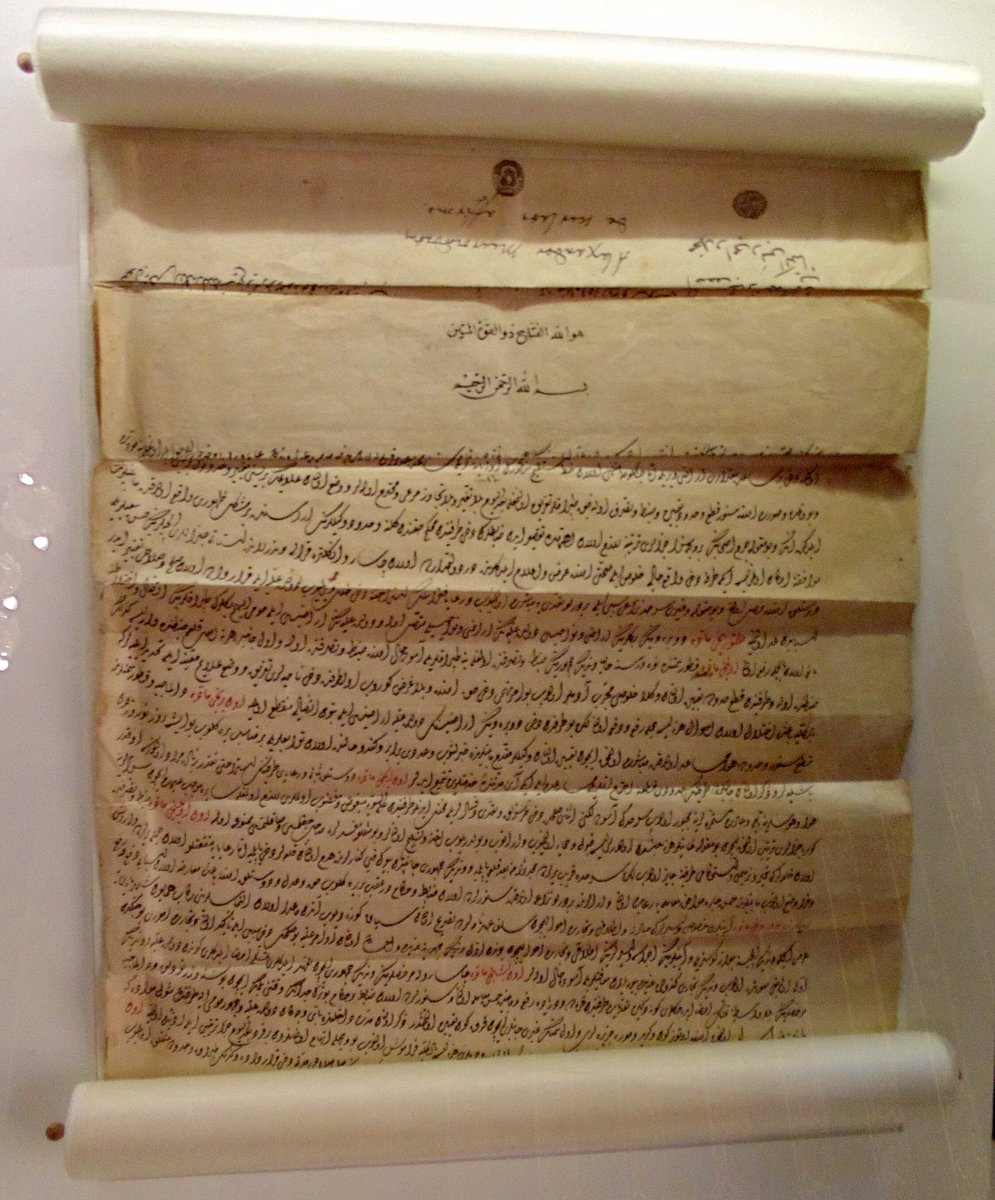

A new pristine interpretation of The Book was the call of the hour.

That’s what the two men did.

A new pristine interpretation of The Book was the call of the hour.

That’s what the two men did.

While the two men didn’t succeed in reviving their respective caliphates, they did in reviving Islam’s hegemony by injecting the community with a renewed sense of ideological puritanism.

Their actions and inspirations continue to inform geopolitics to this day.

Their actions and inspirations continue to inform geopolitics to this day.

While Wahhab’s Wahhabism would go on to inspire the likes of al-Qaeda, Dehlawi’s thoughts crystallized in Deoband which would ultimately spawn the Taliban.

In short, all the violence you see today in the name of Islam trace their origins to the years between 1699 and 1707.

In short, all the violence you see today in the name of Islam trace their origins to the years between 1699 and 1707.

But why am I talking Istanbul and Delhi in the same vein? It’s not like one’s decline impacted the other’s.

Because both declines and the subsequent rise of fanaticism found a common catalyst in a third decline.

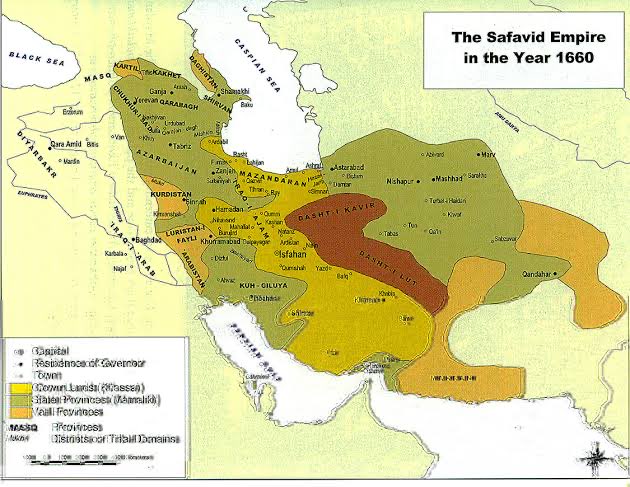

The decline of the Safavids.

Because both declines and the subsequent rise of fanaticism found a common catalyst in a third decline.

The decline of the Safavids.

Within a decade of taking the throne, he’d humbled both Mughals (sack of Delhi) and Ottomans (Battle of Kars).

It’s around this period that Dehlawi and Wahhab shot into theological stardom with their respective maiden works.

It’s around this period that Dehlawi and Wahhab shot into theological stardom with their respective maiden works.

Wahhab’s Kitab at-Tawhid and Dehlawi’s Ḥujjat Allah al-Baligha, both advocated for and reinforced Islam’s return to its absolute, non-negotiable fundaments.

One became the guiding scripture for Wahhabism, the other for Deobandism that’d emerge a century later.

One became the guiding scripture for Wahhabism, the other for Deobandism that’d emerge a century later.

Thus—and in most simplistic, reductive terms—one can see violent geopolitical jihad as a series of dominos, the first of which fell with the defeat of Constantinople…

On January 26, 1699.

To reduce it further, today is the birthday of modern militant jihad.

On January 26, 1699.

To reduce it further, today is the birthday of modern militant jihad.

Loading suggestions...