A Sunday morning read on monetary macroeconomics and the lessons from the Great Reflation (no subscription needed.)

The question is, how did central banks get it so long during the great reflation? A short thread.

moneyinsideout.exantedata.com

The question is, how did central banks get it so long during the great reflation? A short thread.

moneyinsideout.exantedata.com

Focusing on the fiscal-monetary aspects of global inflation (overlooking the energy shock and Brexit) the OECD recently noted "evidence that money growth and inflation have been closely linked recently."

bis.org

bis.org

Yet modern macro models largely ignore the role of money. This can be traced back to Woodford's Interest and Prices which was published 20 years ago.

The reason for doing so was since in practice the policy rate was set exogenously, money was endogenous. And in addition...

The reason for doing so was since in practice the policy rate was set exogenously, money was endogenous. And in addition...

it just so happened a money *demand* equation could be tagged on, but that it plays “no independent role in determining the equilibrium" so could be largely ignored.

The problem with this is that sometimes there can be a money *supply* shock...

The problem with this is that sometimes there can be a money *supply* shock...

This was pointed out by Charles Goodhart in response to a paper by Woodford in 2006 at the ECB where he argued against models with money.

Goodhart noted that sometimes the supply shock can dominate. But what does this mean?

fmg.ac.uk

Goodhart noted that sometimes the supply shock can dominate. But what does this mean?

fmg.ac.uk

When responding to Woodford's cashless agenda, Goodhart ends the paper with a decision tree. If M growth is not consistent targets, policymaker should ask if it is demand or supply shock. If the former, ignore. If the latter, it matters—and ought to elicit a policy response.

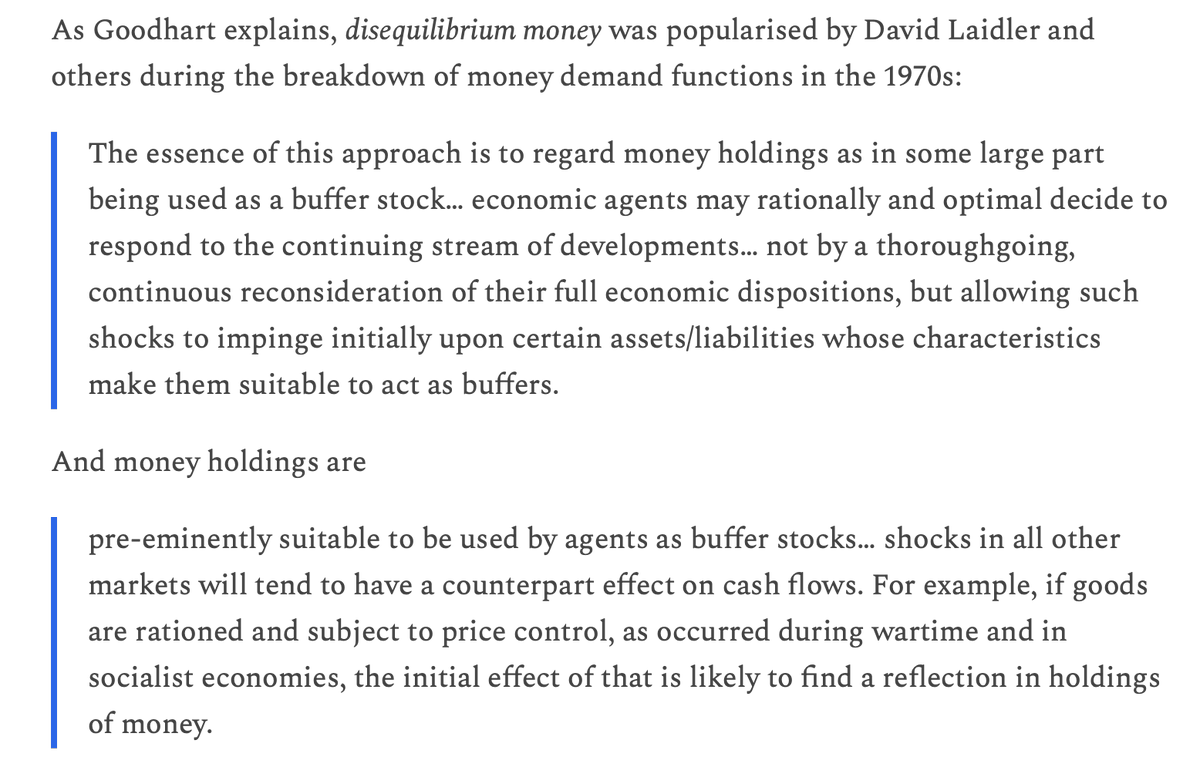

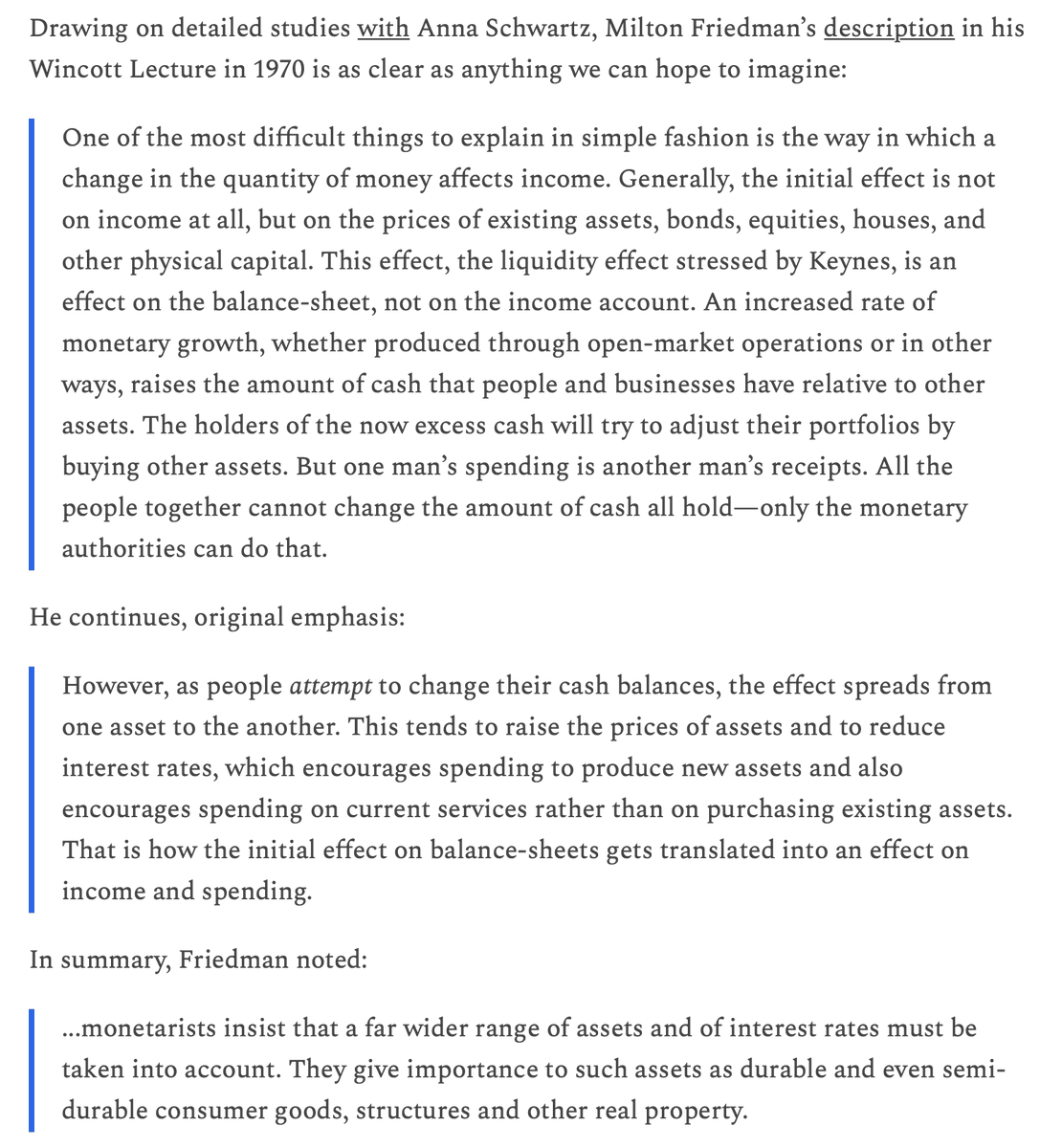

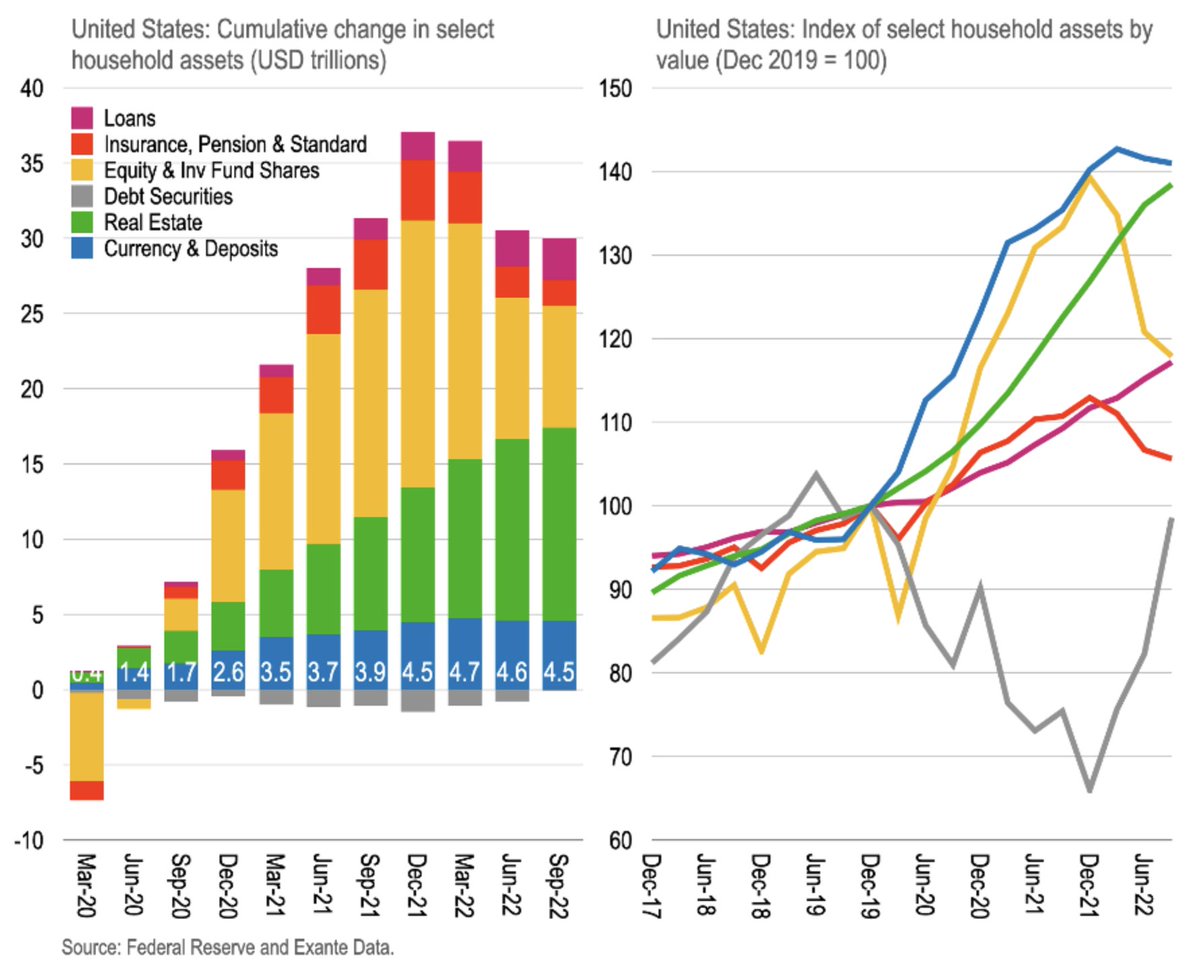

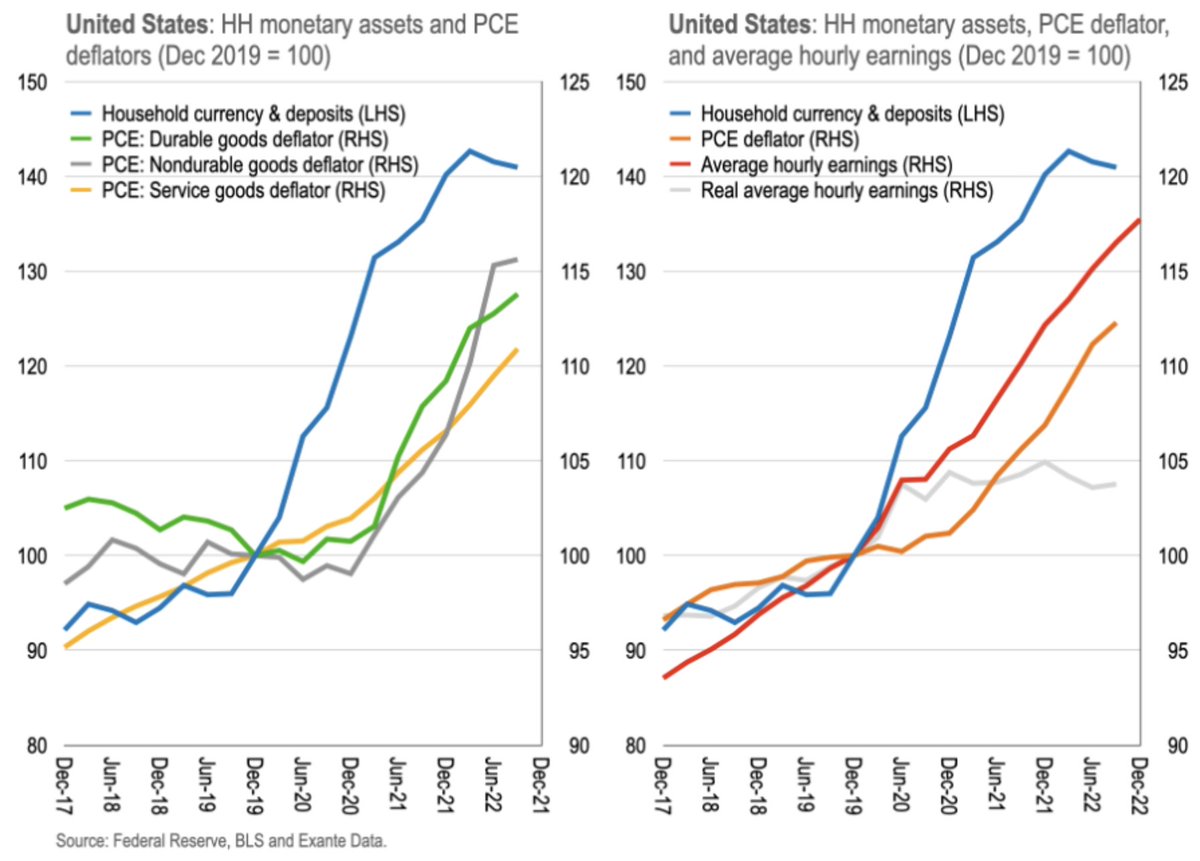

What happened in the pandemic, of course, was a huge money supply shock as policy monetary-fiscal interventions were seen again in the buffer of money.

But what do we know about such disequilibria? Well, there is a literature on unwinding monetary overhangs.

But what do we know about such disequilibria? Well, there is a literature on unwinding monetary overhangs.

For Dornbusch overhangs could be managed in two ways. First, a “big, possibly one-shot inflation” to return real money balances to their equilibrium levels. Second, money could be “immobilised” by being “written off, consolidated as debt or retired by asset exchanges...” etc.

Curiously, inflation will only continue if there is an underlying flow problem that remains. And historically, “the release of a monetary overhang does not result in permanent inflation, much less a hyperinflation.”

#A01ref10" target="_blank" rel="noopener" onclick="event.stopPropagation()">elibrary.imf.org

#A01ref10" target="_blank" rel="noopener" onclick="event.stopPropagation()">elibrary.imf.org

In a sense then, Friedman was right; the monetarist description of transmission played out pretty well.

Where does this leave us? Well, during the Great Reflation central banks were reactive rather than proactive, responding to inflation rather than inflation targeting proper.

Where does this leave us? Well, during the Great Reflation central banks were reactive rather than proactive, responding to inflation rather than inflation targeting proper.

That’s a sign a panic.

One reason for this is the new Keynesian work which encouraged the idea that money could be ignored—but as Goodhart warned at the time, there was a risk that the implications of a money supply shock would be missed.

One reason for this is the new Keynesian work which encouraged the idea that money could be ignored—but as Goodhart warned at the time, there was a risk that the implications of a money supply shock would be missed.

And the pandemic created for the community a huge money supply shock—and this disequilibrium is being unconsciously unwound through inflation.

Official post mortems for our recent experience will be interesting. Australia has a review of the RBA next month, for example.

Official post mortems for our recent experience will be interesting. Australia has a review of the RBA next month, for example.

But in reflecting upon our recent monetary malaise, we might recall once more the fact that monetary macroeconomics continually fails to integrate balance sheets and financial structures.

This time, central banks have been blindsided in the pandemic as household balance sheets strengthened—a decade ago, fiscal policy was calibrated without due regard for household balance sheet weakness.

Once again, full post here with more detail (for free). @jnordvig @ExanteData @ExanteInsights @EtraAlex

Comments very welcome as this is a work-in-progress:

moneyinsideout.exantedata.com

Comments very welcome as this is a work-in-progress:

moneyinsideout.exantedata.com

Loading suggestions...