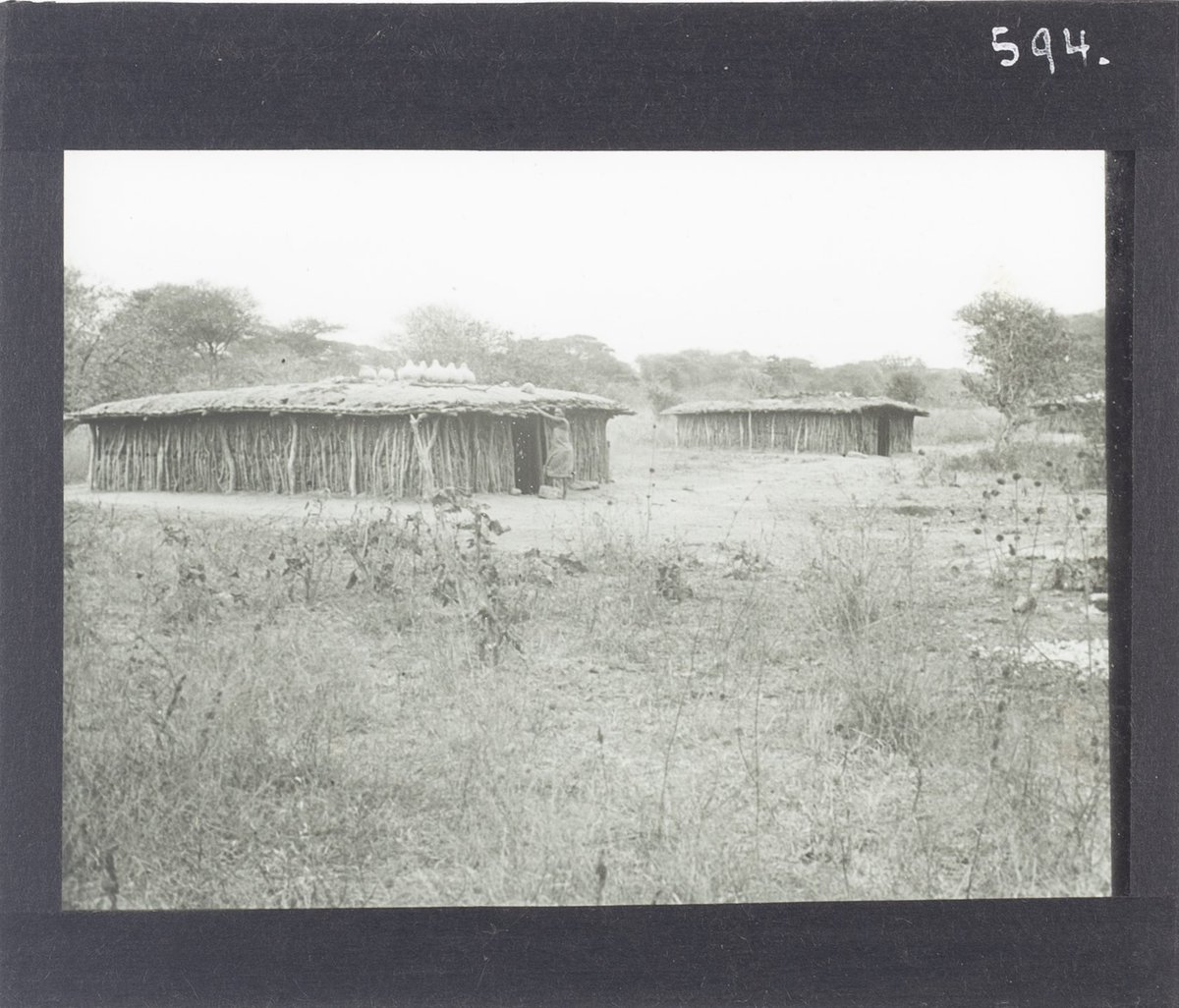

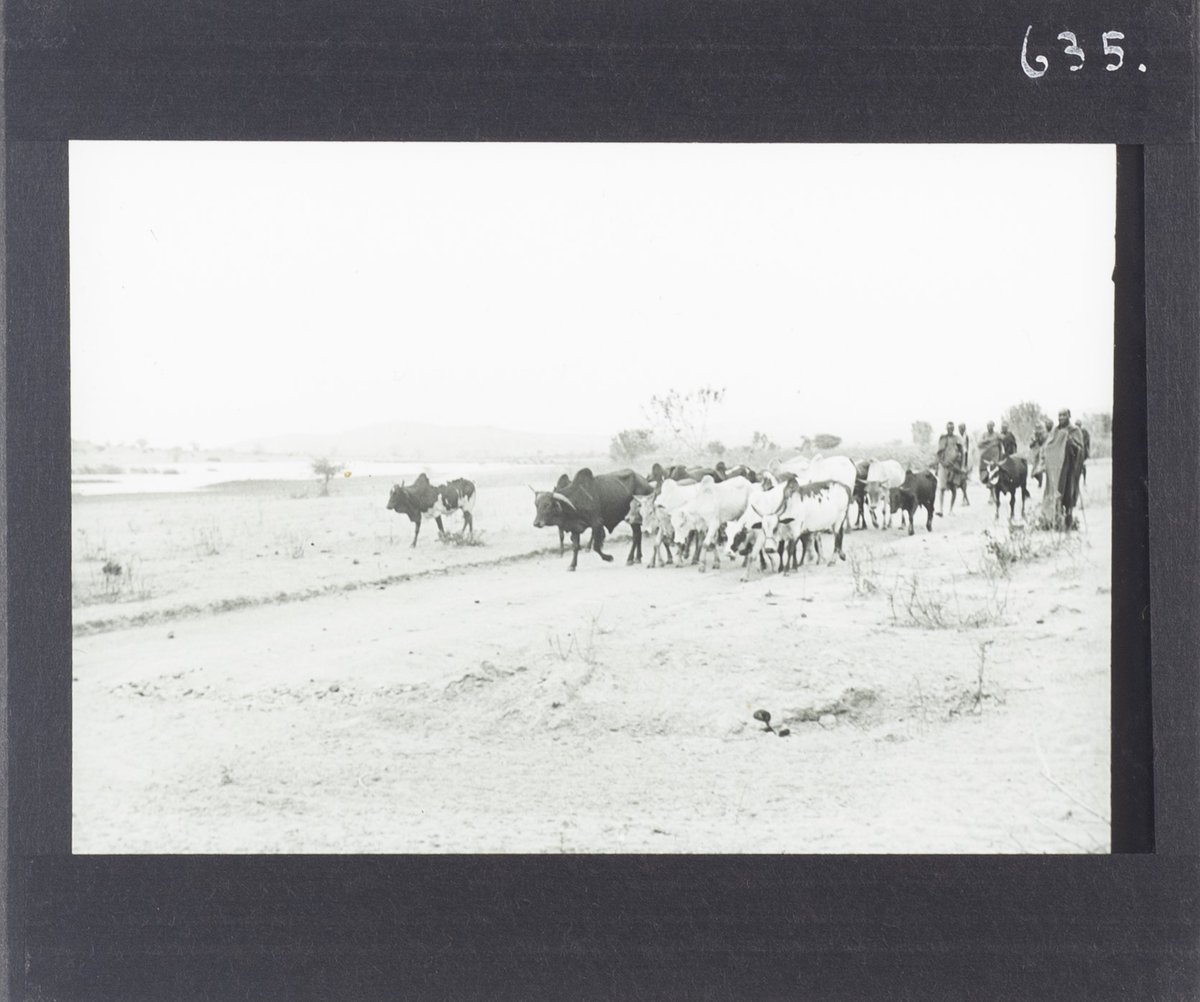

As a primarily pastoralist community, Maasai people have for centuries had deep respect and care for their natural environment.

The relationship between the community and the environment is not one of resource extraction rather one of mutual respect, care and benefit.

The relationship between the community and the environment is not one of resource extraction rather one of mutual respect, care and benefit.

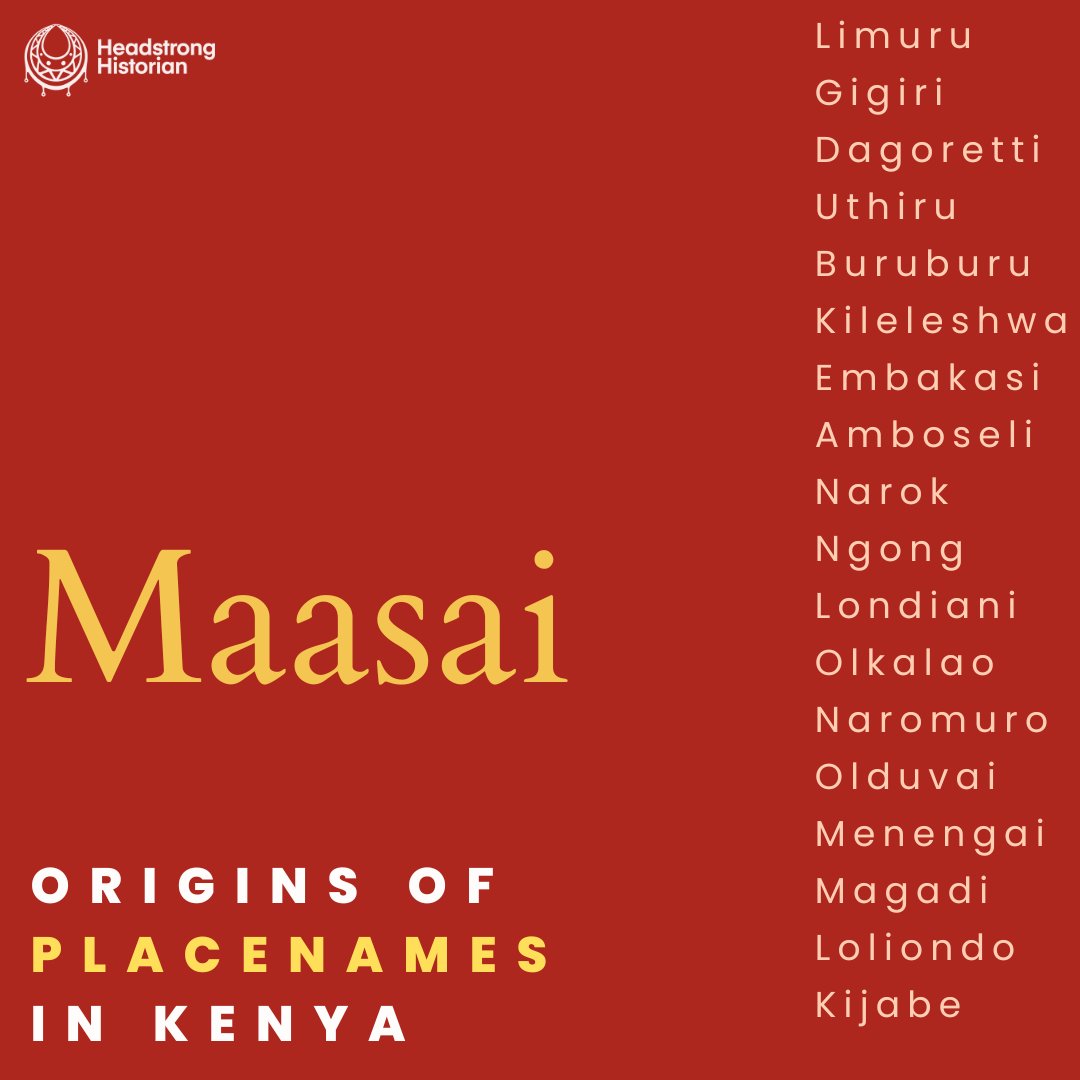

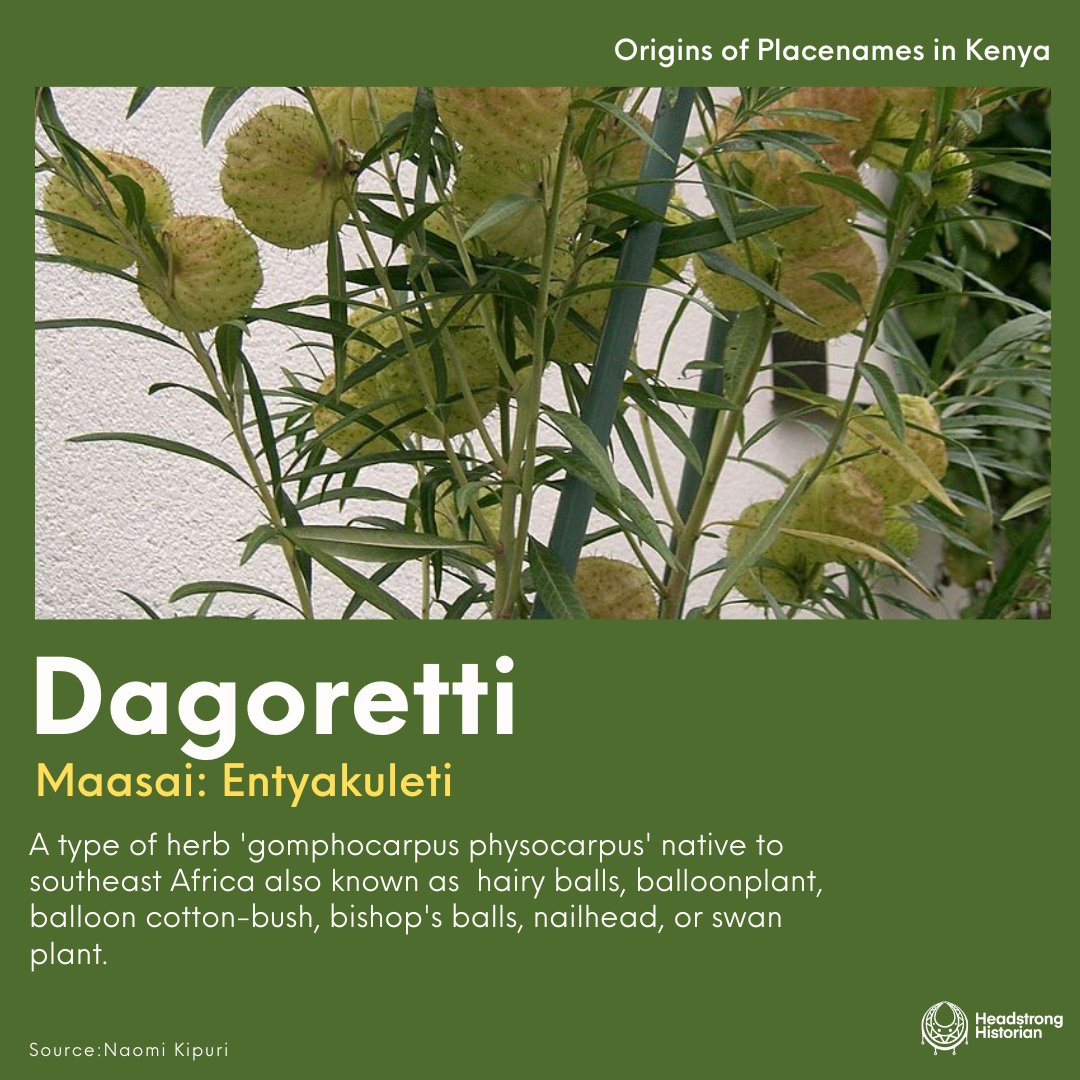

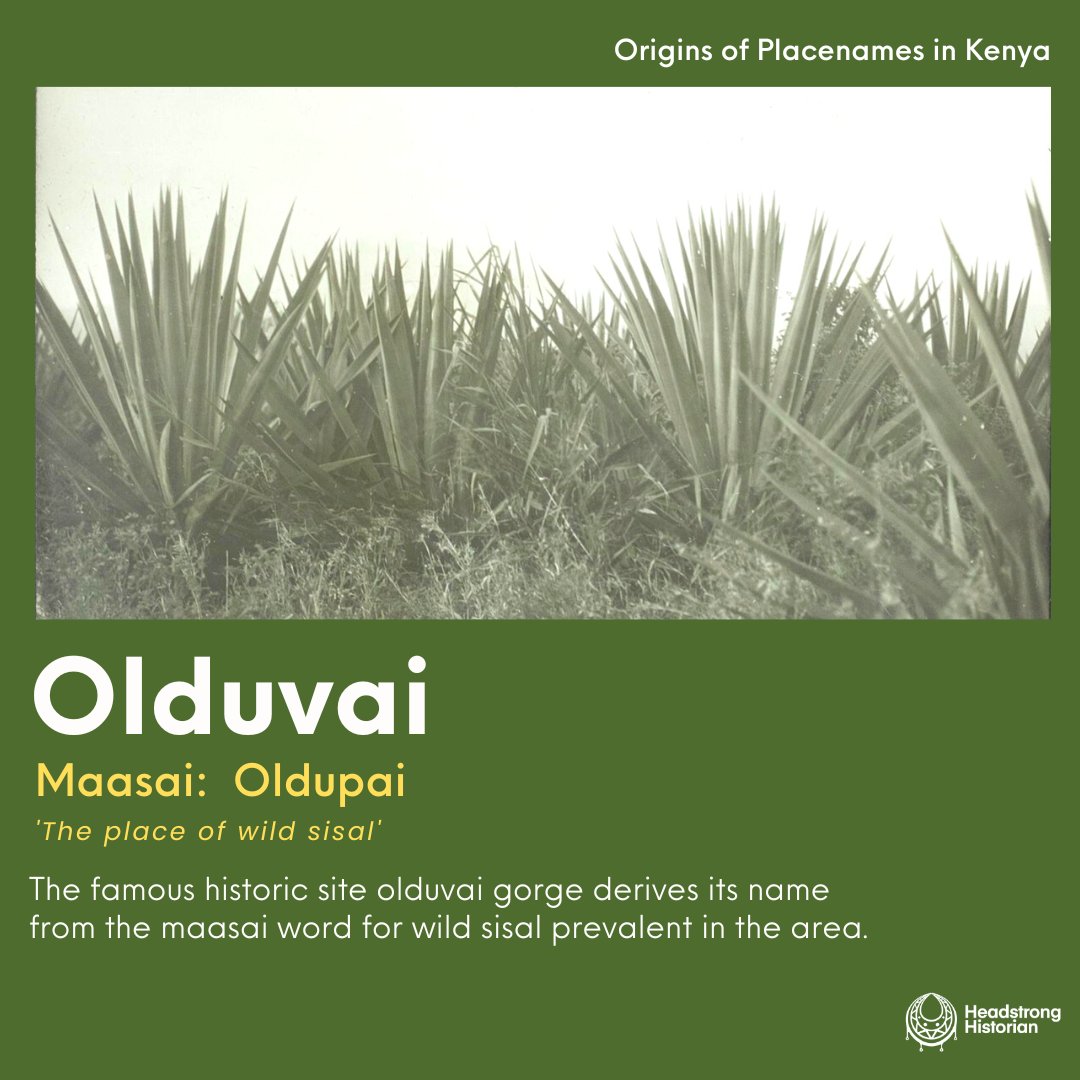

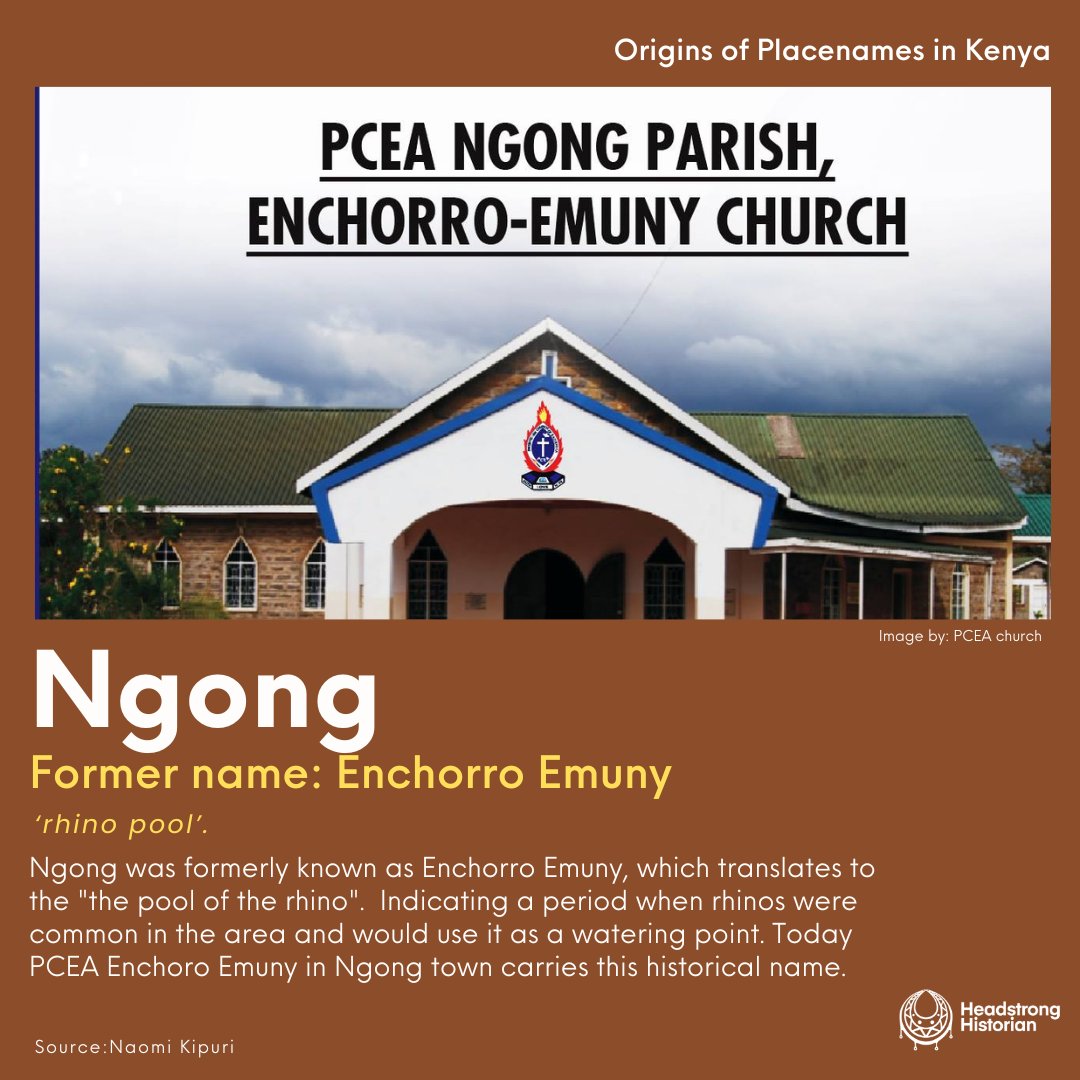

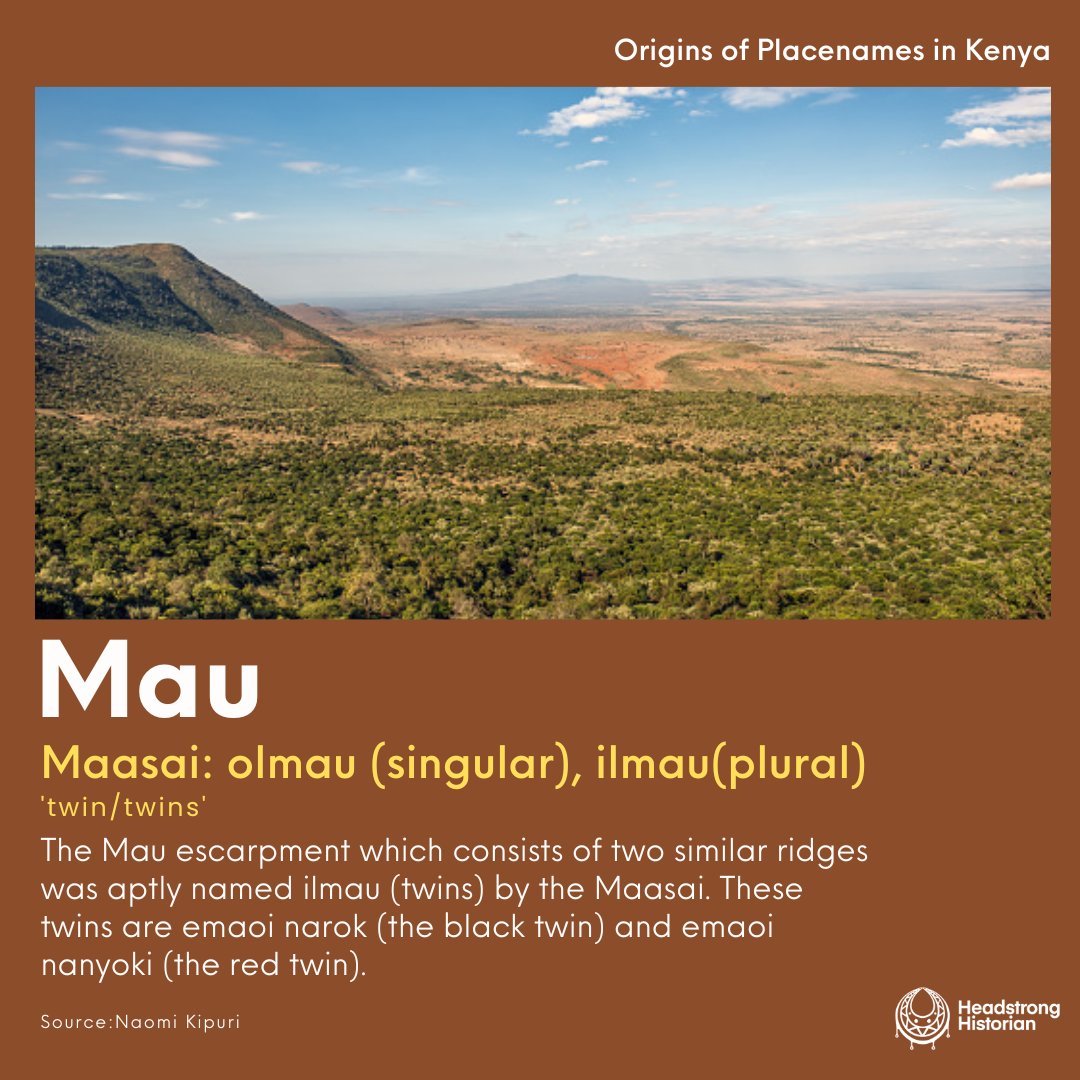

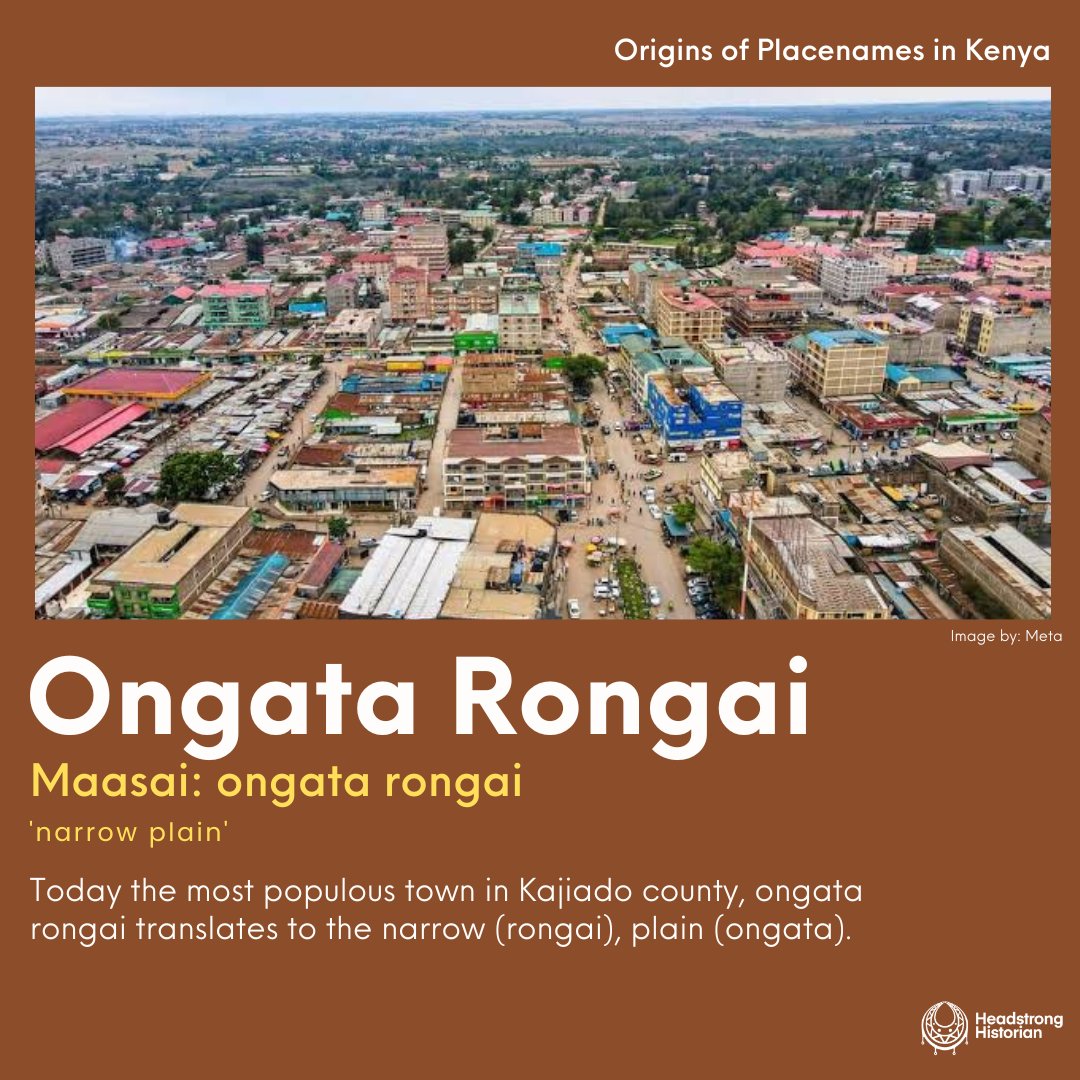

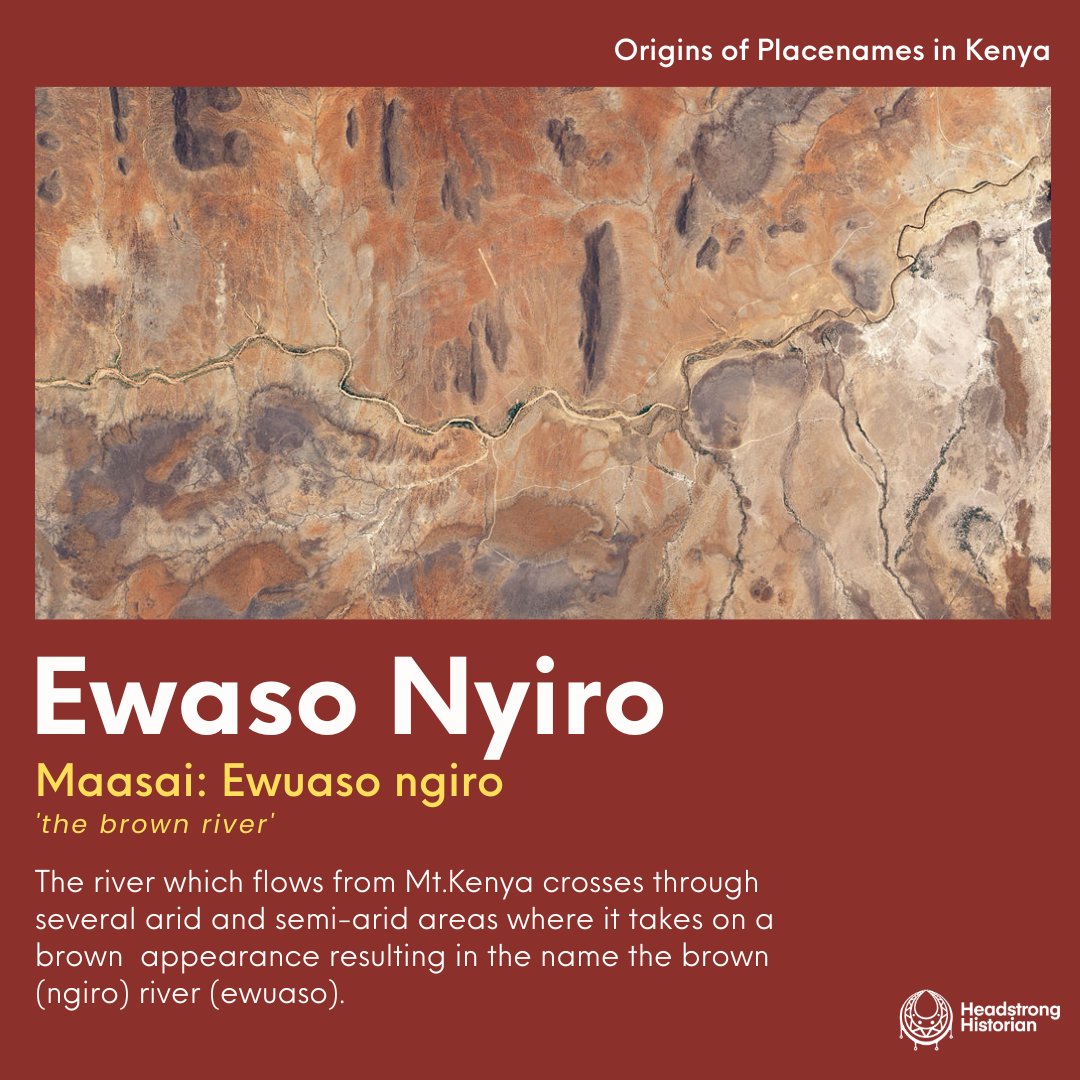

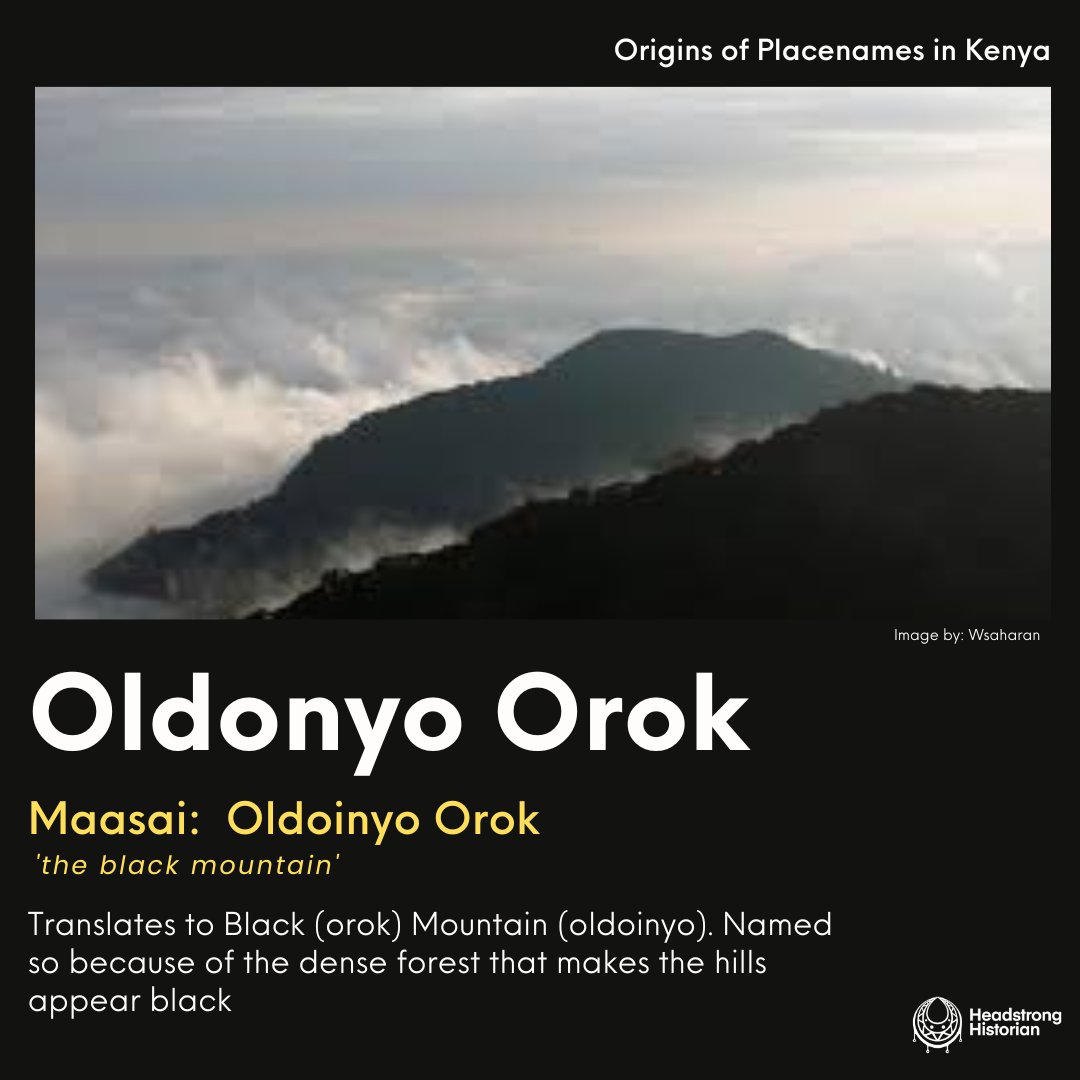

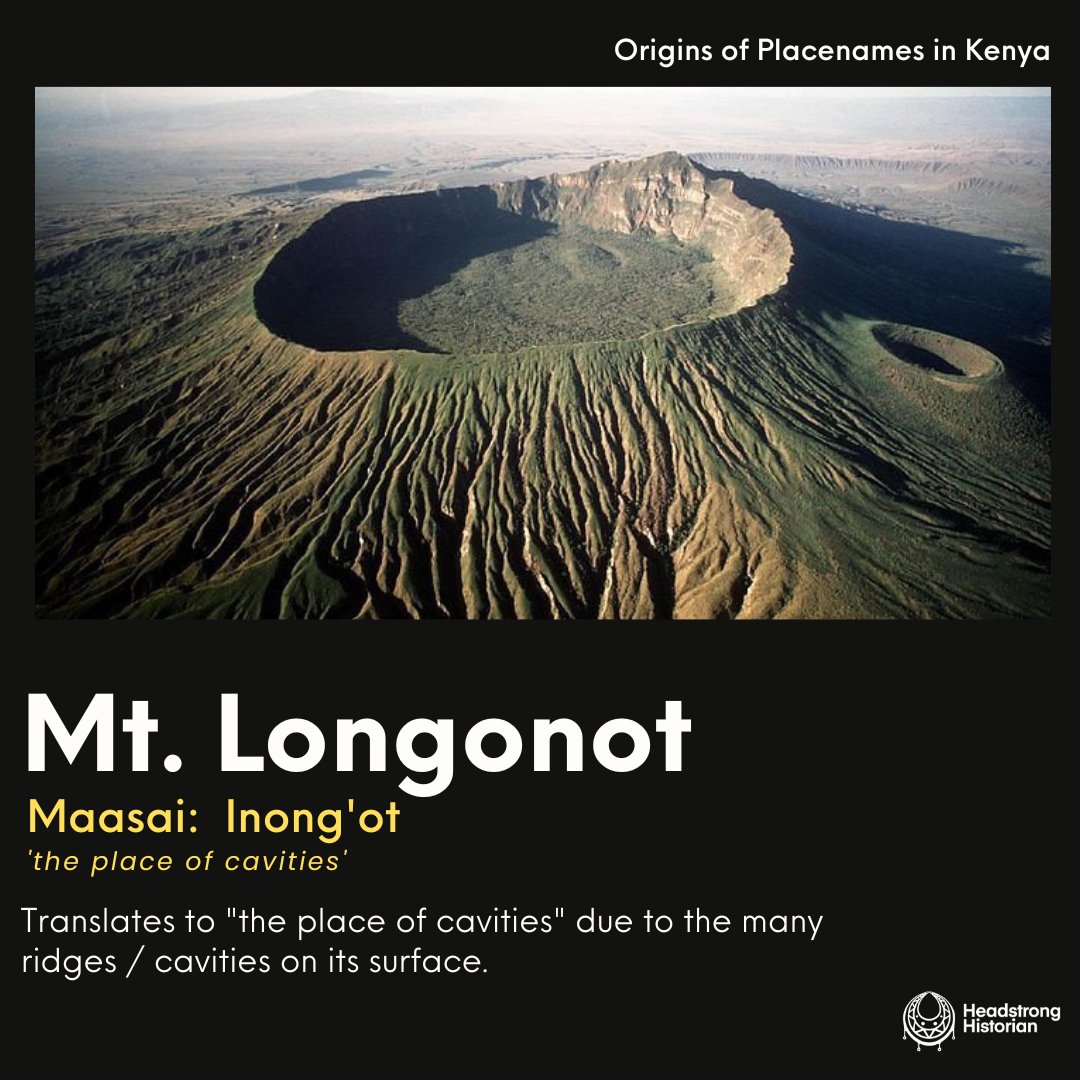

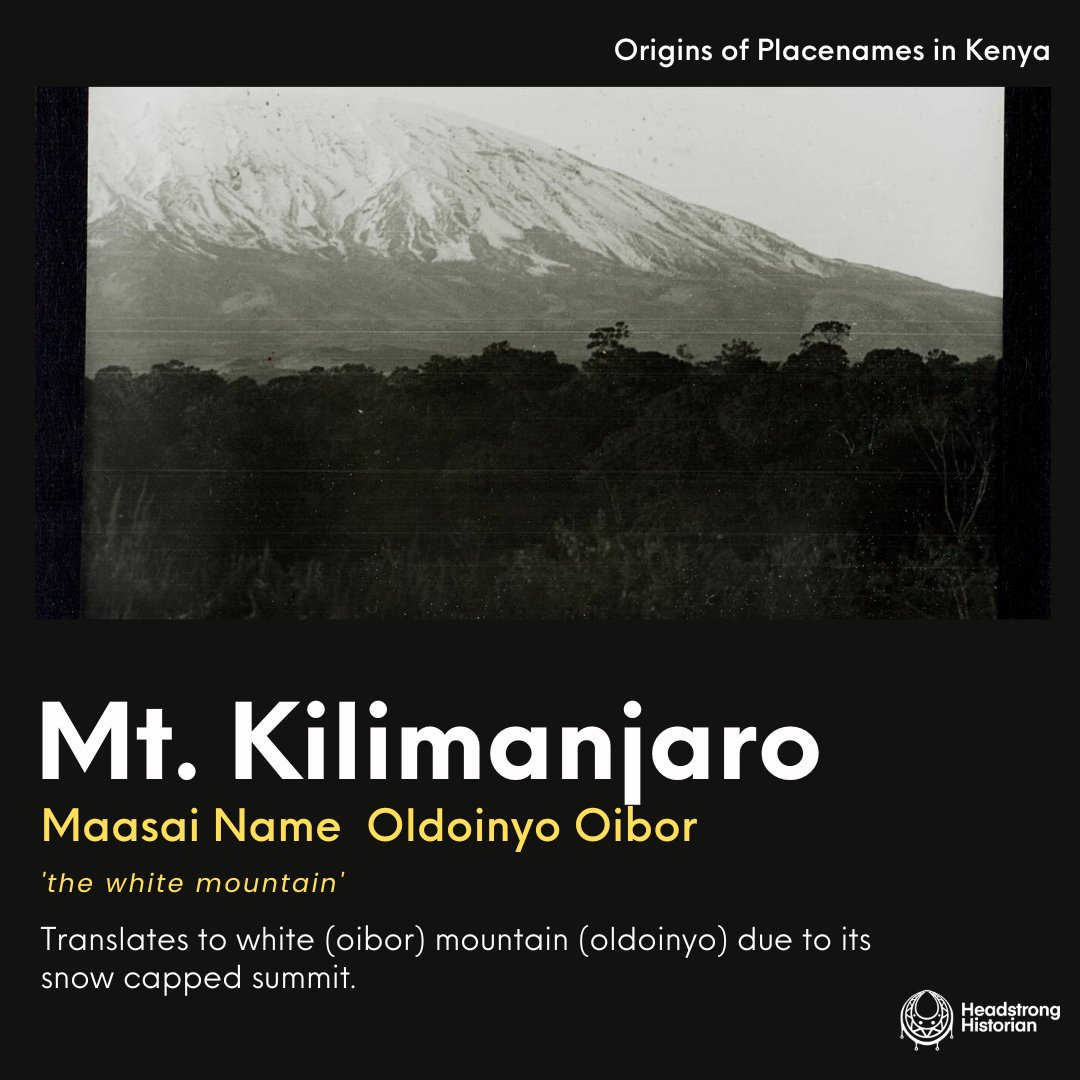

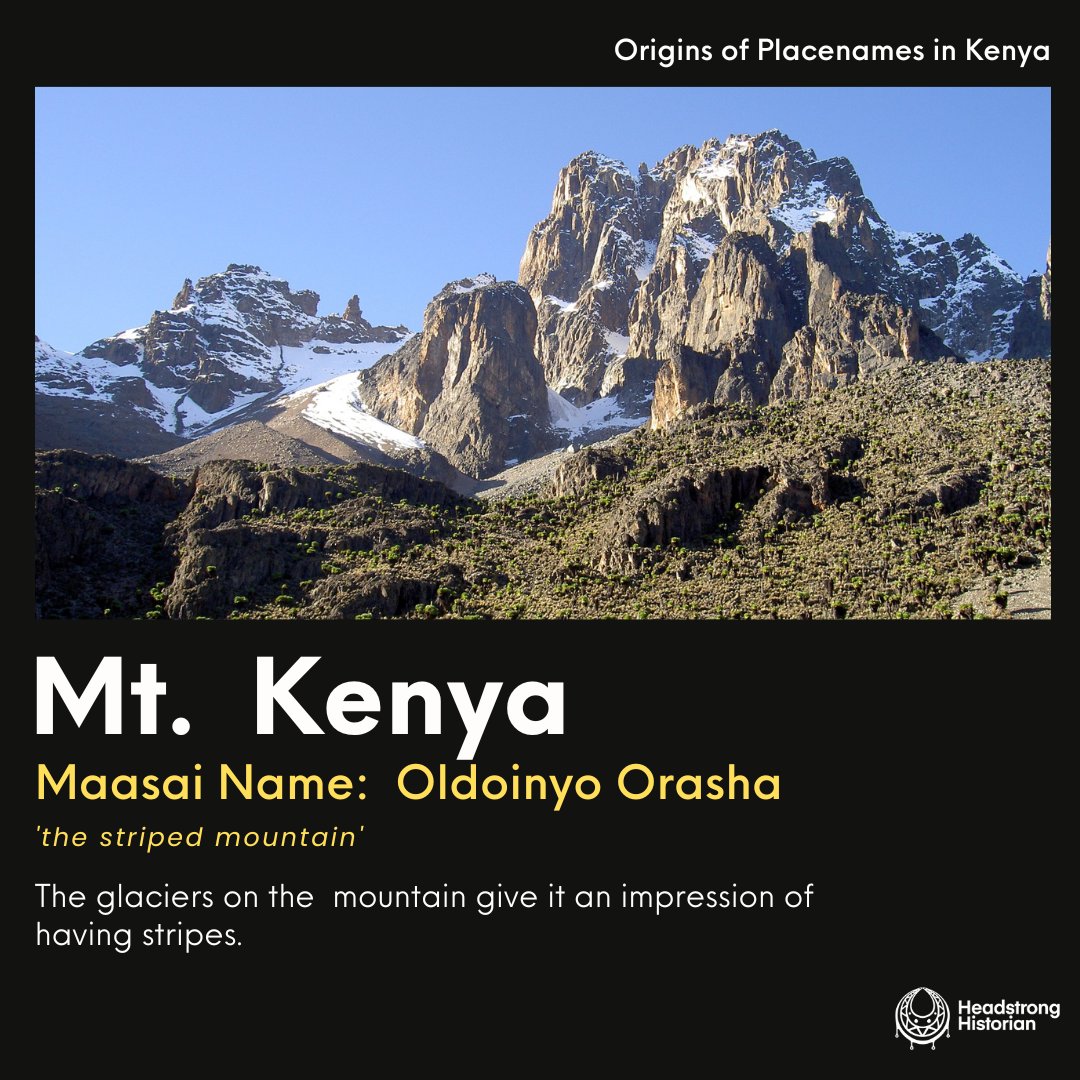

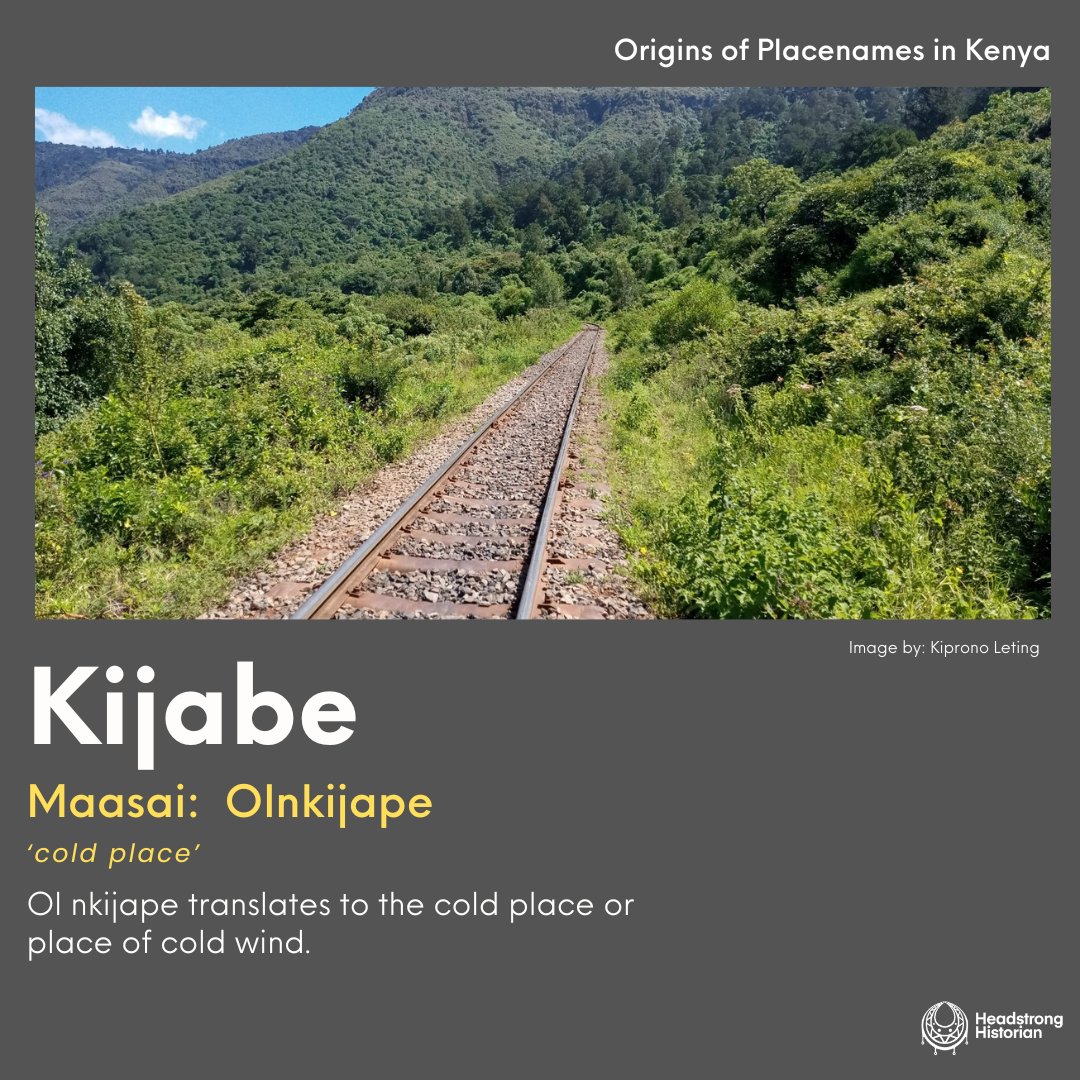

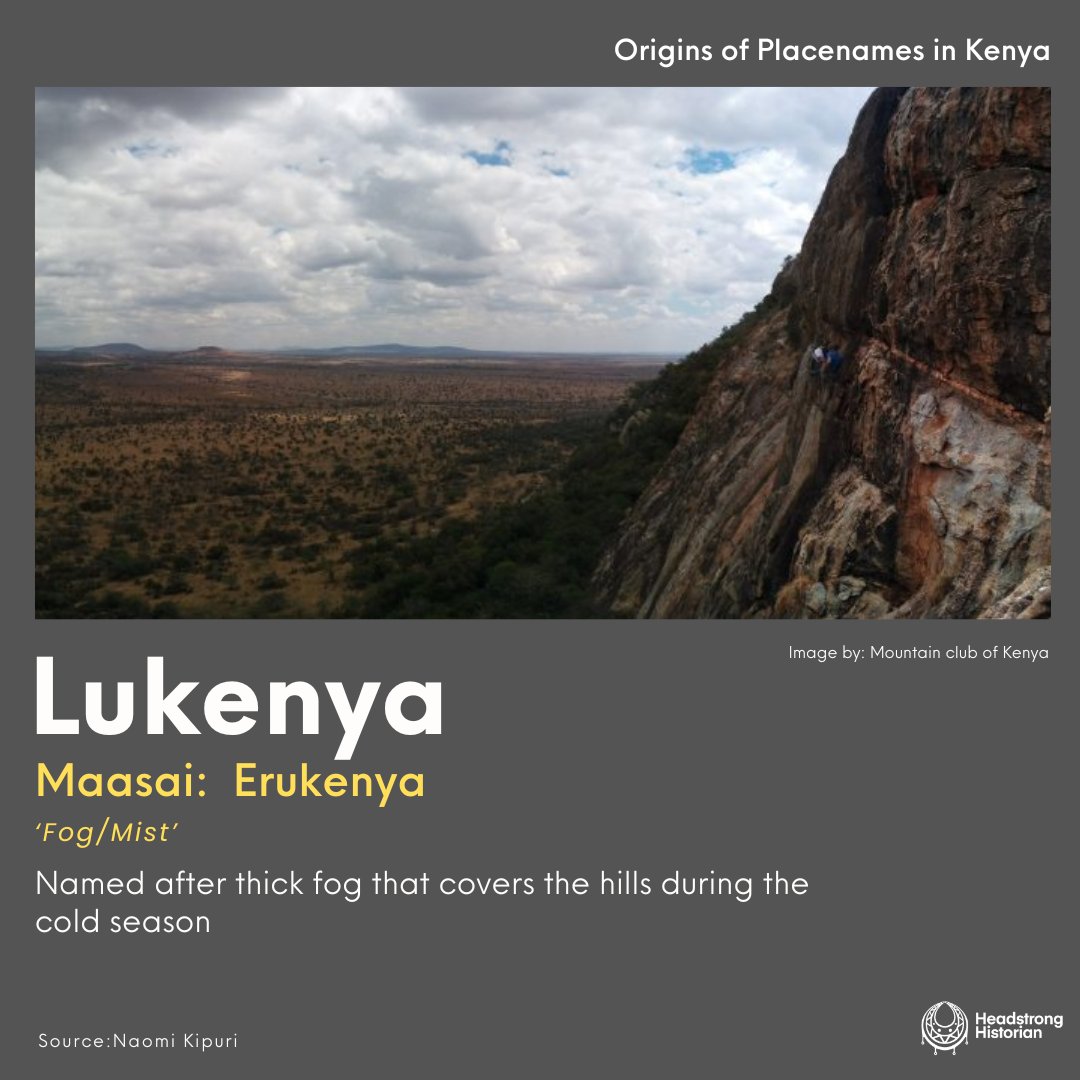

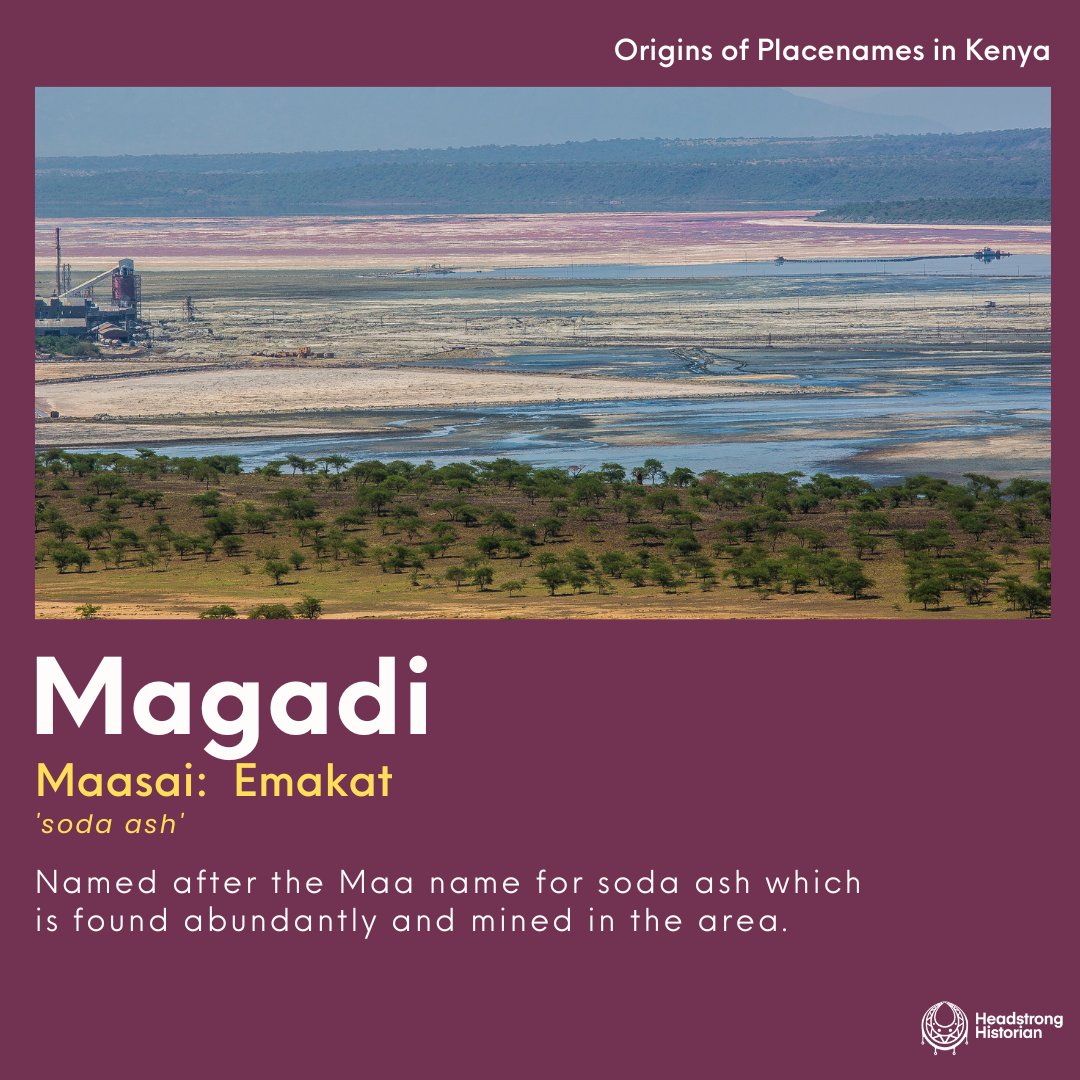

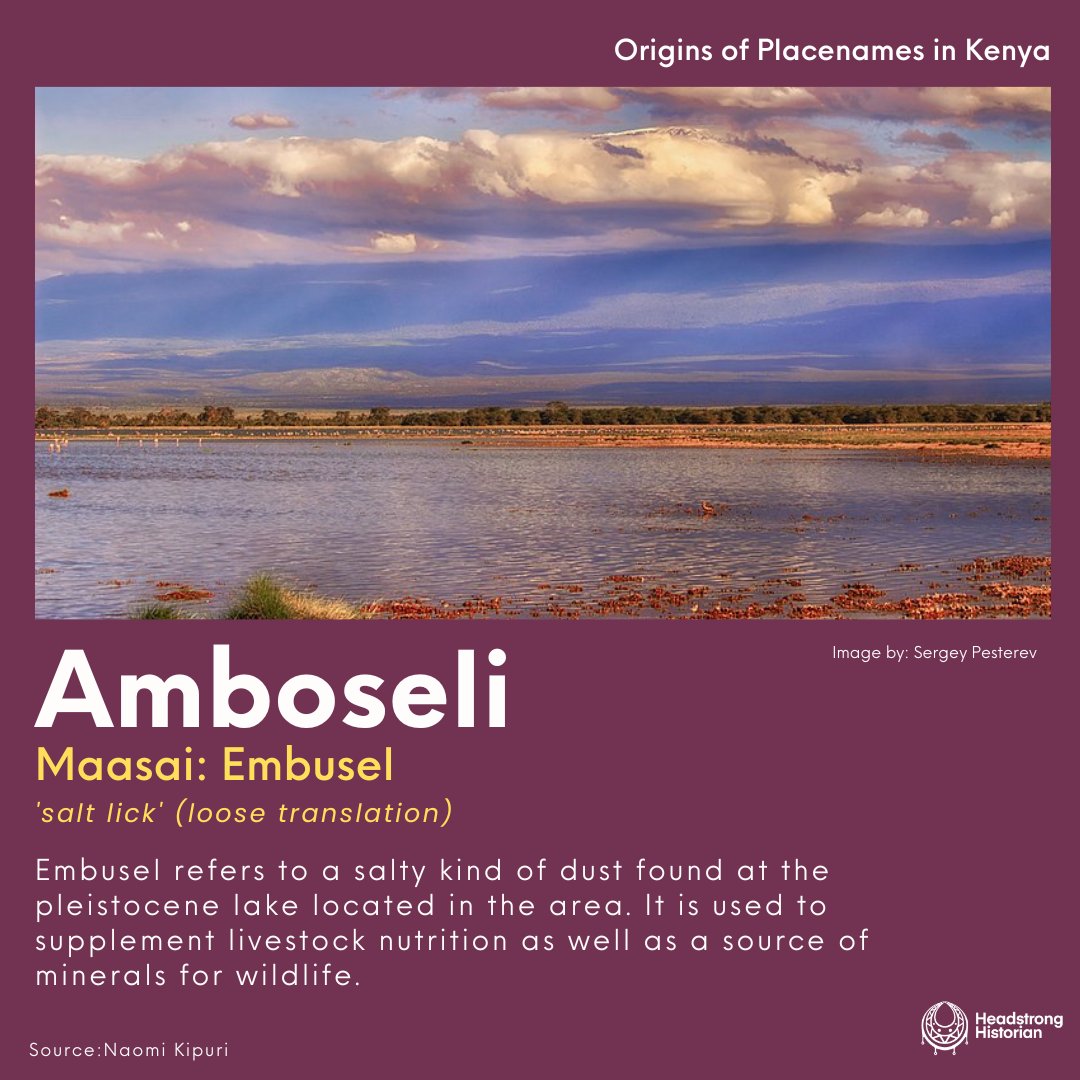

One of the ways in which this geographical knowledge was transmitted was through language and place naming

As we begin, it is important to note many of these names have changed spelling and pronunciation based on interactions with other languages such as Kamba, Gikuyu, English..

As we begin, it is important to note many of these names have changed spelling and pronunciation based on interactions with other languages such as Kamba, Gikuyu, English..

Dr.Naomi Kipury whose work informs this research notes that we can categorize Maasai geographical names based on: plant life, natural features, colors and patterns, topography, animals, and legends.

Personally fascinated by this last category and the histories that could be extrapolated from this, like what happened to the Salei? 🤔

This is by no means a conclusive list and there are so many names that could be added.

But I would like to take a brief moment to talk about what these place names signify and how they challenge us to expand our understanding of where history lives.

But I would like to take a brief moment to talk about what these place names signify and how they challenge us to expand our understanding of where history lives.

Understanding the origins of place names demonstrates the power of language and orality as a crucial historical archive.

Early notions of Africans having no history due to 'lack of written records' point to European ignorance of the complexities of indigenous knowledge systems where history was a living thing, embodied in people, places, relationships and environment.

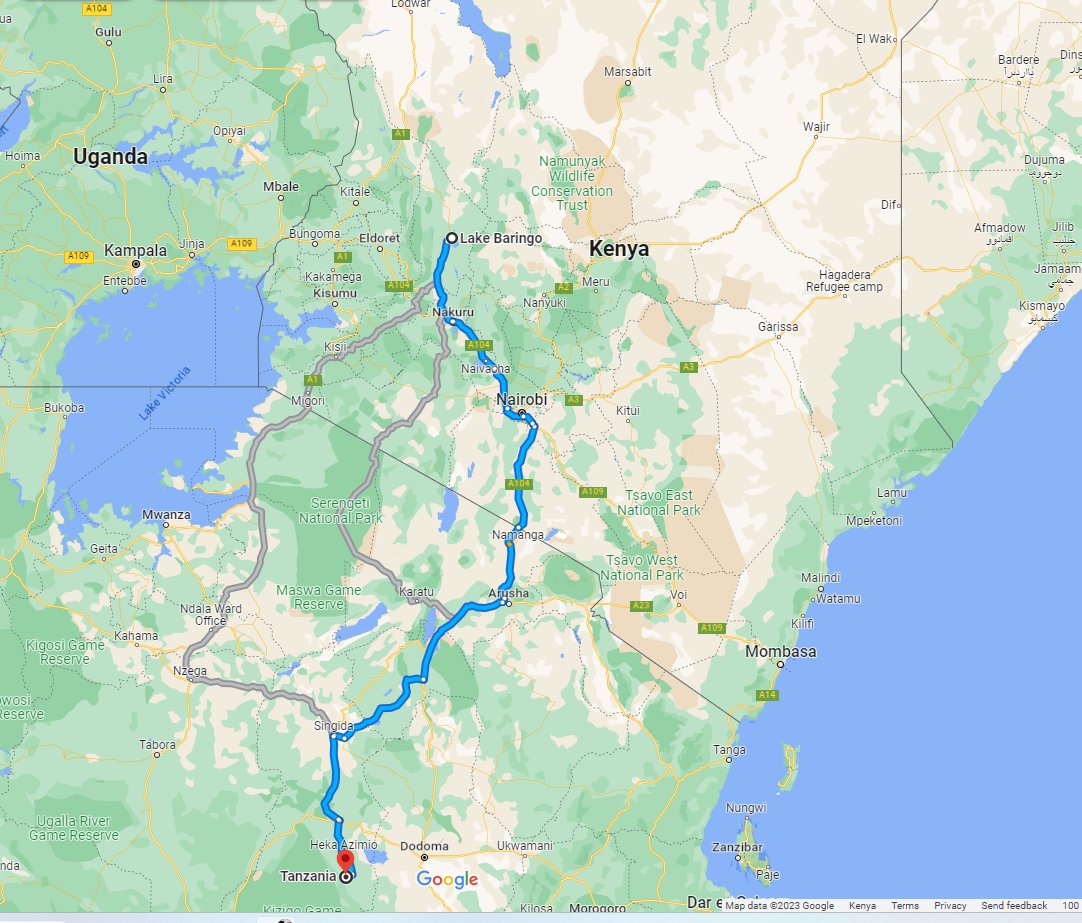

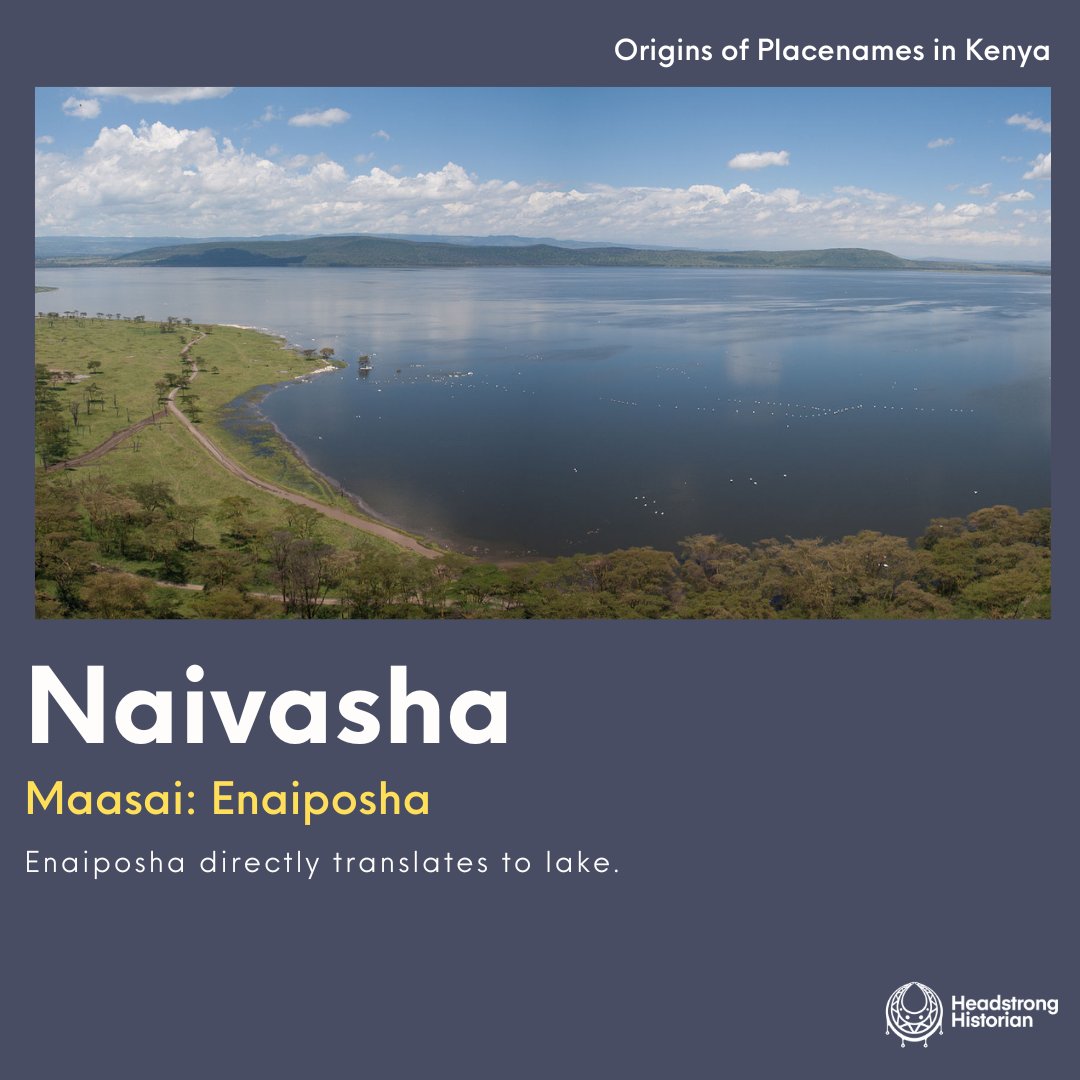

Through this small sample of Maasai place names we are able to map out the spread of indigenous plant species, origins of water sources, geographical formations, animal migration patterns, historical events and so much more...

The ways in which place names have changed to match the phonetics of different communities can also reveal the history of migration, settlement and interactions between different groups.

What can we tell about the interactions between Maasai and Kipsigis by exploring the a place like Londiani?

Using this approach everything is intertwined language, landscape, people.. a steep departure from a history in which communities are presented as existing in silos

Using this approach everything is intertwined language, landscape, people.. a steep departure from a history in which communities are presented as existing in silos

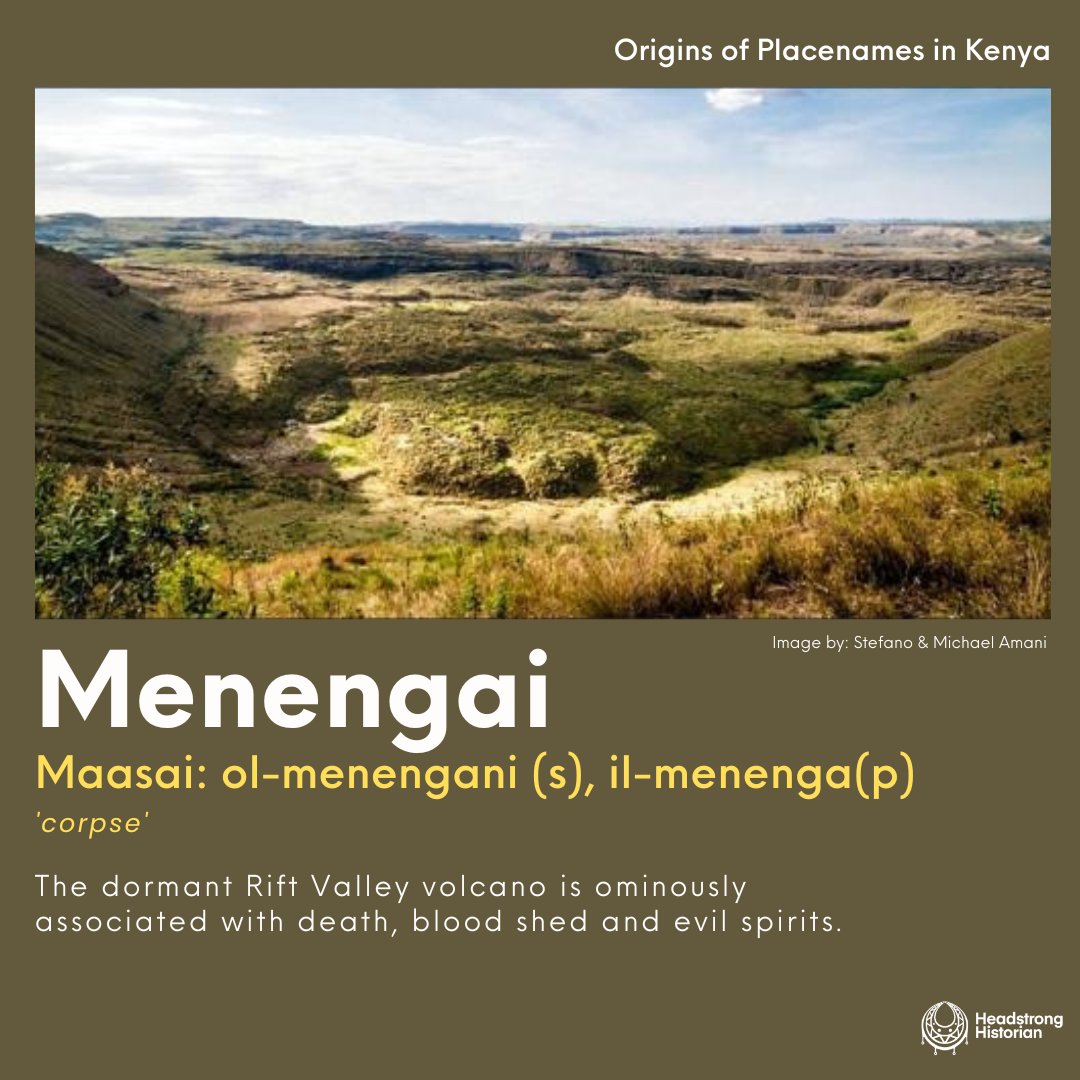

It is also interesting to note that some place names have contested origins.

A place such as Menengai is said to have Maa, Kikuyu and Kipsigis origins. Beyond conversations on which is ‘more legitimate’ the real conversation is what does this tell us about their interactions?

A place such as Menengai is said to have Maa, Kikuyu and Kipsigis origins. Beyond conversations on which is ‘more legitimate’ the real conversation is what does this tell us about their interactions?

Beyond Maasai, this exercise can also be done with different languages from multiple communities. What insight can we draw that can help us in conversations around climate change, food systems, wildlife management and so much more?

The preservation and use of indigenous languages is also the preservation of entire archives of knowledge.

This not about history being something we consume as a hobby but something that is extremely functional in helping us make sense of our environments and futures.

This not about history being something we consume as a hobby but something that is extremely functional in helping us make sense of our environments and futures.

2022 saw the violent eviction of Ngorongoro's Maasai community over claims that the community is a danger to wildlife.

Our histories and languages prove that this is a fiction that only exists in the minds of capitalist and exploitative regimes

Our histories and languages prove that this is a fiction that only exists in the minds of capitalist and exploitative regimes

There is so much I could write but at the risk of not making this thread longer I will end it here.

Thankful for the work of Dr.Naomi Kipury, David Ole Munke and S Ole Sankan.

Thankful for the work of Dr.Naomi Kipury, David Ole Munke and S Ole Sankan.

Loading suggestions...