“Much native scholarly output on Dacia during the communist period was rooted in the thesis whereby somehow, the Dacians were an ancient super-race that actually gave the Romans the Latin language earlier in antiquity.”

“Dacia, a unique case study of ‘barbarian’ Europe, at its twin peaks under Burebista and later Decebalus, was not only the largest barbarian kingdom, but also one of the few with institutions robust enough to survive the cyclical boom-bust nature of barbarian tribal power.”

“The Helvetii tribe, which gave Caesar the cover to begin the conquest of Gaul, migrated because Burebista had conquered west up to the Moravian plain and caused various barbarian tribes like the Boii to migrate westwards and push the Helvetii out of their ancestral homes.”

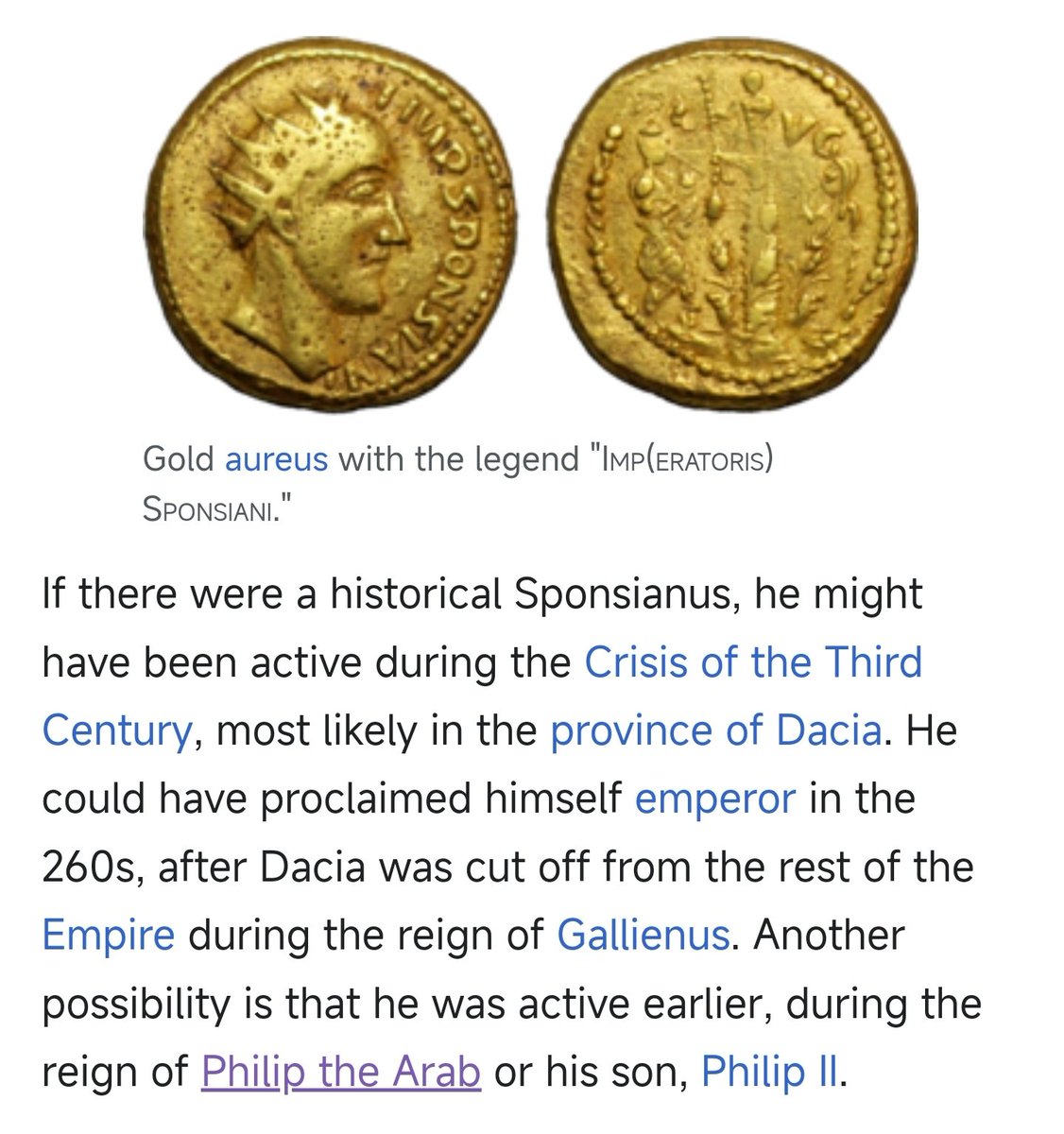

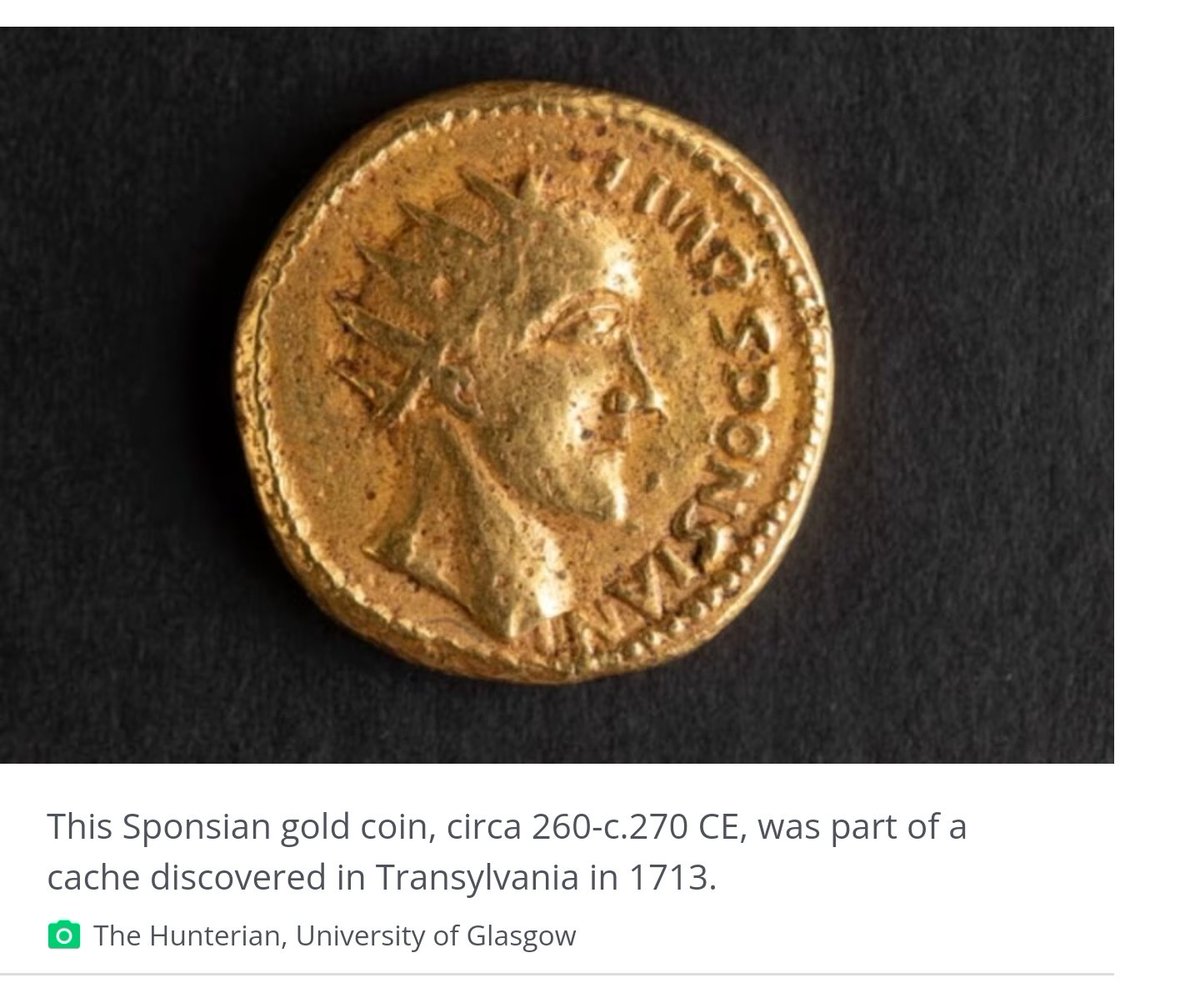

The Roman province of Dacia, a territory overlapping with modern-day Romania, was a region prized for its gold mines. The area was cut off from the rest of the Roman empire in around 260 CE.

At the time of their discovery, the coins were deemed authentic. But doubts about their authenticity grew over time, and in 1868, French numismatist Henri Cohen declared the Sponsian coins to be "very poor quality modern forgeries".

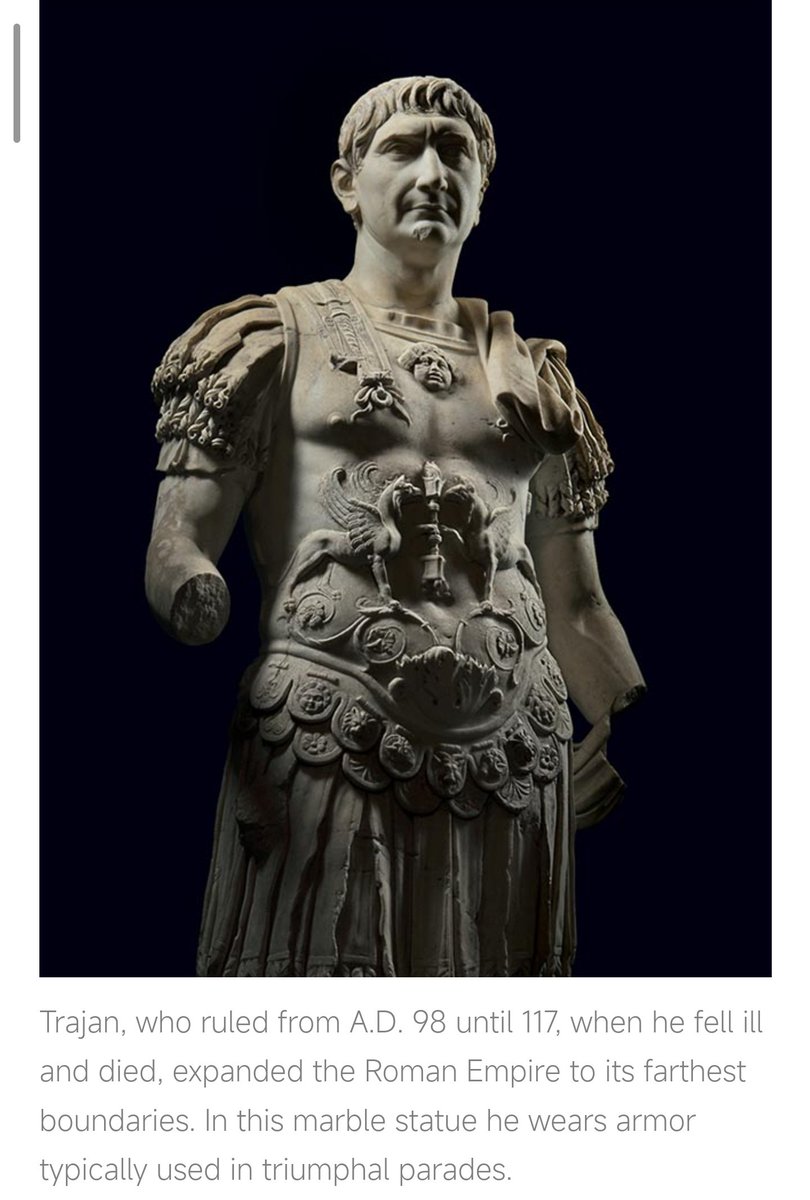

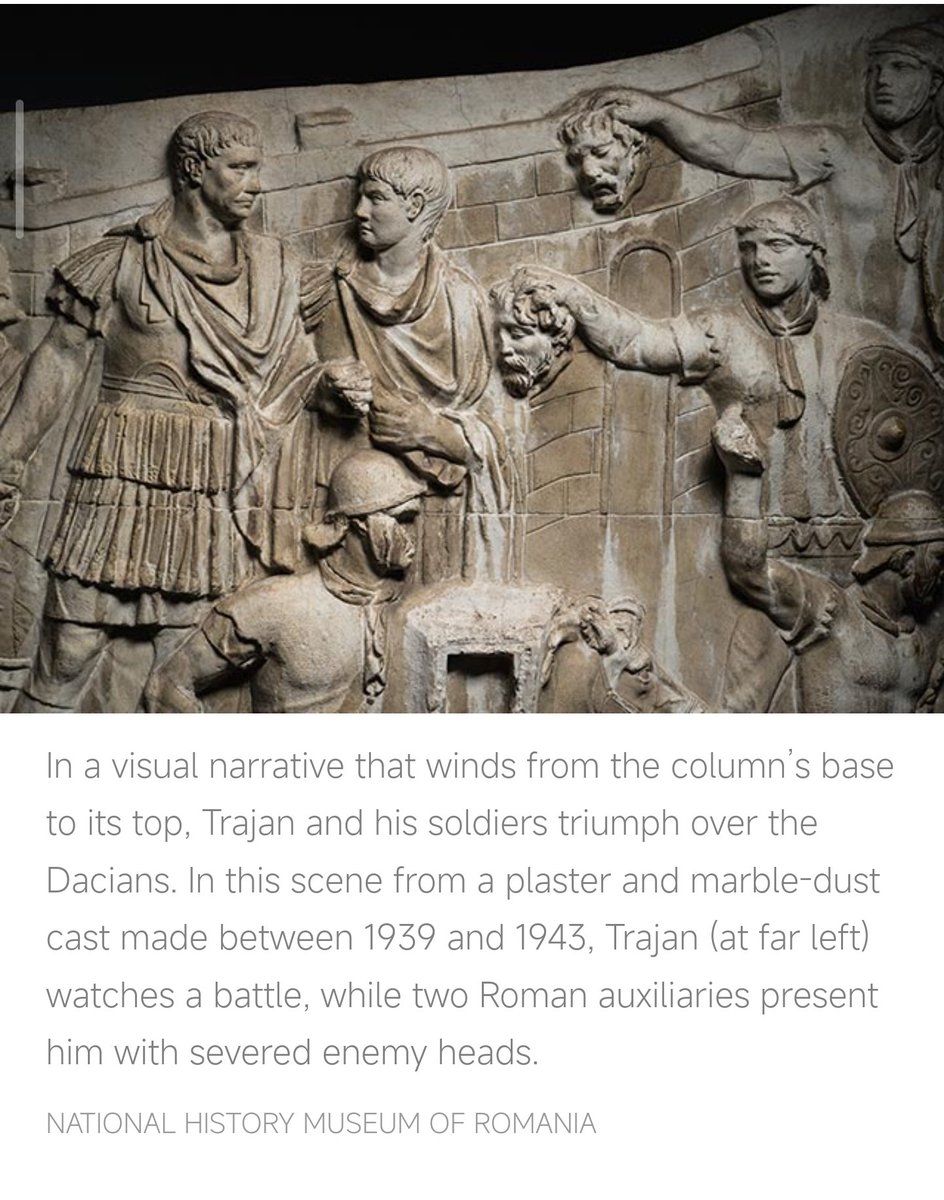

Trajan’s war on the Dacians was the defining event of his 19-year rule. The loot he brought back was staggering. One contemporary chronicler boasted that the conquest yielded a half million pounds of gold and a million pounds of silver, not to mention a fertile new province.

The booty changed the landscape of Rome itself. To commemorate the victory, Trajan commissioned a forum that included a spacious plaza surrounded by colonnades, two libraries, a grand civic space known as the Basilica Ulpia, and possibly even a temple.

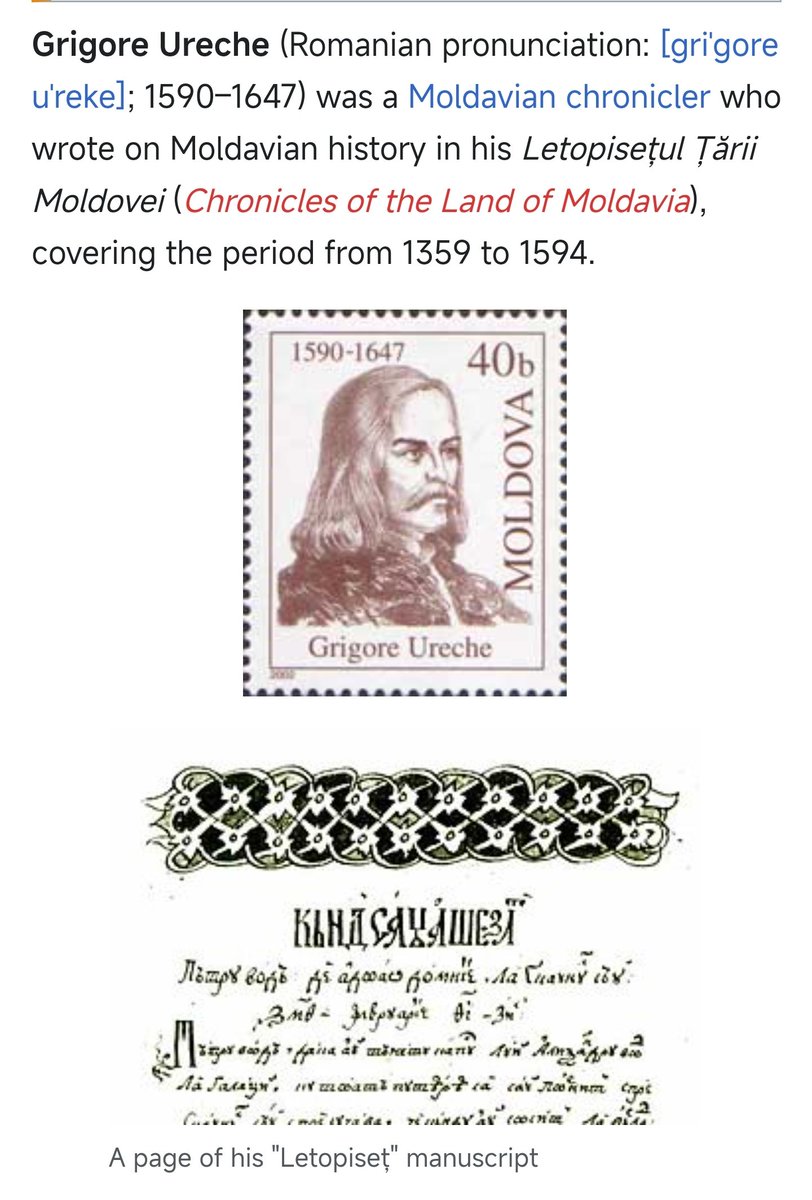

In Romanian historiography it was Grigore Ureche (1590-1647), towards the middle of the seventeenth century, who first noted that the origin of the Romanians was in “Rim”.

books.openedition.org

books.openedition.org

With the exception of Constantin Cantacuzino, who accepted a Daco-Roman mixing in his History of Wallachia, the chroniclers and later historians would agree to nothing less than a pure Roman origin, with the Dacians exterminated or expelled to make way for the conquerors.

The Dacians' never-contested love of liberty and spirit of sacrifice seemed, to the romantic revolutionary generation, to be virtues worthy of admiration and imitation.

For all the concessions made towards them, the Dacians appear in the romantic period — until after 1850 — more as mythical ancestor figures, sunk deep into a time before history, in a land which still recalled their untamed courage.

The Thracians, and thus the Dacians, symbolized rootedness in the soil of the land; the Romans the political principle and civilization; while the Celts deserved to be invoked since through them Romanians could be more closely related to the French.

During the communist period, the Romans were consistently referred to as invaders, and their departure from Dacia was seen as a liberation.

Whether good or bad — generally bad at the beginning and good later on — the Romans only represented one episode in a history that stretched over millennia.

There was a certain agitation, too, around the insoluble question of the Dacian language. Whether it was a “Latin” language or different from Latin, it demanded to be reconstituted and perhaps even established as a subject in the university curriculum.

The ongoing match between the Dacians and the Romans was somewhat complicated by the additional involvement of the Slav factor. The Slavs, as is well known, had a significant influence on the Romanian language, as well as on early Romanian institutions and culture.

Loading suggestions...