Money printing doesn't work like you think.

A thread.

1/

A thread.

1/

Without properly understanding money, it’s basically impossible to connect the dots of the global macro puzzle

Yet, we assume we know all about money

Universities teach us that governments need money to fund their spending, Central Banks print the money we use, and banks...

2/

Yet, we assume we know all about money

Universities teach us that governments need money to fund their spending, Central Banks print the money we use, and banks...

2/

...lend and multiply customers’ money in a fractional reserve banking system

That’s literally all wrong

Our monetary system runs on two distinct tiers of money: real-economy money (potentially inflationary) and financial-sector money (potentially asset-price inflationary

3/

That’s literally all wrong

Our monetary system runs on two distinct tiers of money: real-economy money (potentially inflationary) and financial-sector money (potentially asset-price inflationary

3/

Governments and commercial banks print real-economy money.

Central Banks print financial-sector money.

Let's precisely define the two forms of money.

4/

Central Banks print financial-sector money.

Let's precisely define the two forms of money.

4/

Real-economy money is money used by us: non-financial private sector agents (e.g. households, corporates).

With it, we make transactions that contribute to economic activity.

The more real-economy money out there, the more likely economic growth will be stronger.

5/

With it, we make transactions that contribute to economic activity.

The more real-economy money out there, the more likely economic growth will be stronger.

5/

Also, a rapid increase in real-economy money when the supply of goods and services can’t keep up will most likely generate strong inflationary pressures

Financial-sector money is money used by financial entities: mostly banks, but also pension funds, asset managers etc

6/

Financial-sector money is money used by financial entities: mostly banks, but also pension funds, asset managers etc

6/

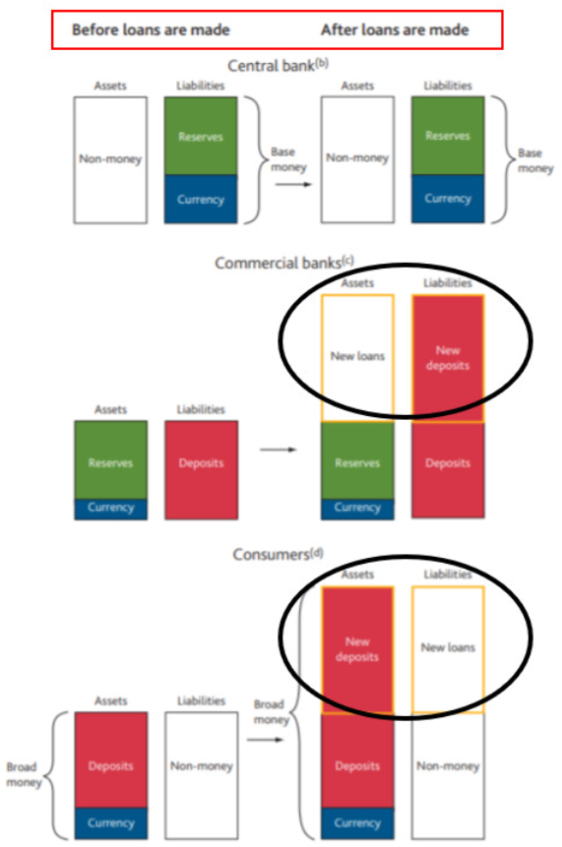

Banks don't lend reserves or existing deposits: as the Bank of England itself shows, when making new loans banks expand their balance sheet and literally credit your account out of nowhere.

Did you notice how the amount of reserves is irrelevant in the lending process?

8/

Did you notice how the amount of reserves is irrelevant in the lending process?

8/

Banks' lending activity depends on:

1) The creditworthiness of the borrowers

2) The attractiveness of loan yields

3) The required capital and balance sheet costs (i.e. regulatory constraints)

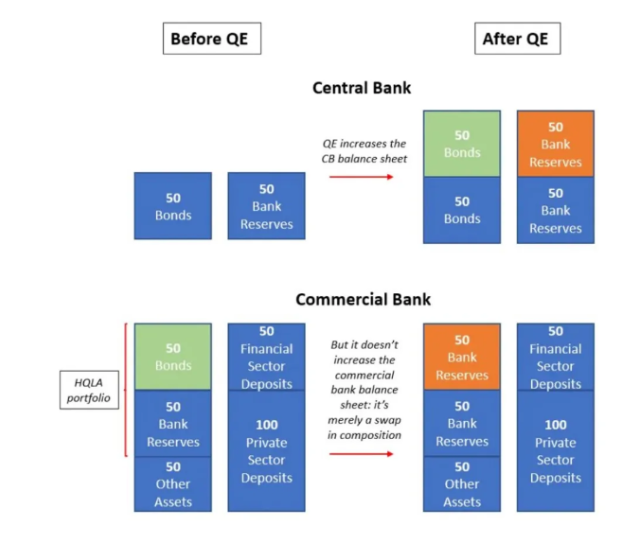

More QE = more financial-sector money.

Not real-economy money.

9/

1) The creditworthiness of the borrowers

2) The attractiveness of loan yields

3) The required capital and balance sheet costs (i.e. regulatory constraints)

More QE = more financial-sector money.

Not real-economy money.

9/

Conclusion: banks print real-economy money.

The other real-economy money printer is the government: come again?

Yep.

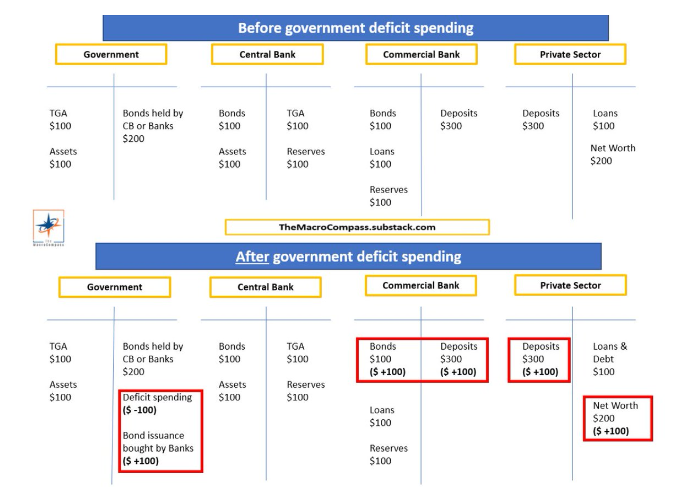

If the government spends more than it plans to collect taxes for (deficits), in most cases new real-economy money has been created.

10/

The other real-economy money printer is the government: come again?

Yep.

If the government spends more than it plans to collect taxes for (deficits), in most cases new real-economy money has been created.

10/

Deficit spending increases the amount of non-financial private sector deposits (i.e. real-economy money) as long as households don’t need to purchase the Treasuries issued by the government itself.

This means deficit spending prints real-economy money...

12/

This means deficit spending prints real-economy money...

12/

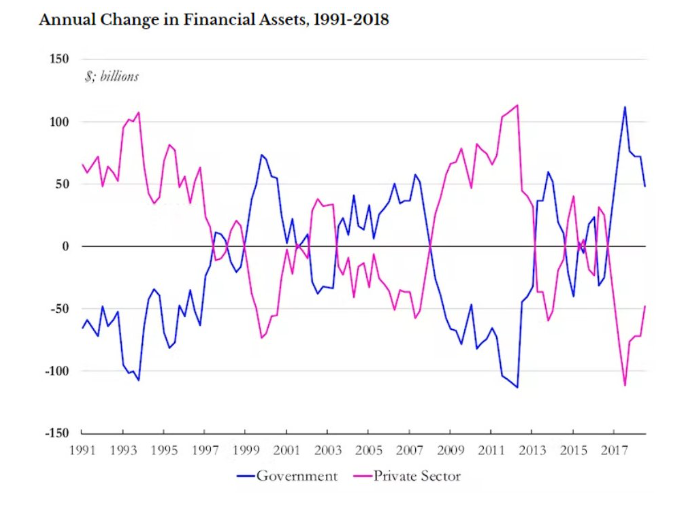

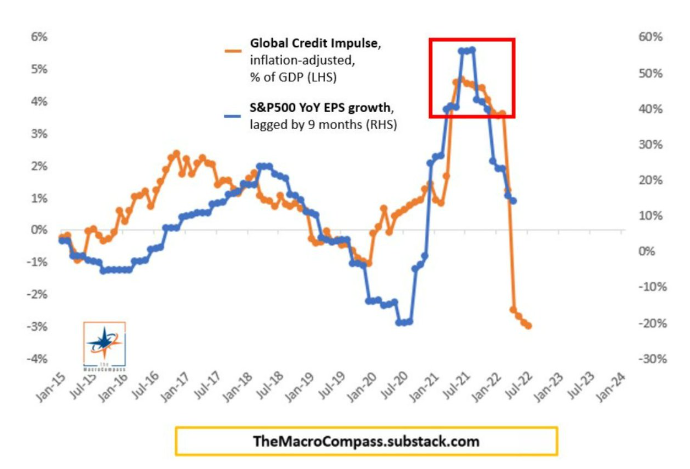

As shown, banks and the government print real-economy money.

Credit creation boosts aggregate demand and it can lead to inflationary pressures.

That's exactly what we have seen in 2020-2021: massive fiscal deficits & government-sponsored bank lending ended up overheating..

14/

Credit creation boosts aggregate demand and it can lead to inflationary pressures.

That's exactly what we have seen in 2020-2021: massive fiscal deficits & government-sponsored bank lending ended up overheating..

14/

As you can see: rapid changes in the amount of real-economy money anticipate rapid changes in economic growth.

So: (in most cases) government deficits and bank lending prints real-economy money.

Not Central Banks - they print financial-sector money.

16/

So: (in most cases) government deficits and bank lending prints real-economy money.

Not Central Banks - they print financial-sector money.

16/

Via QE and other monpol operations, Central Banks print bank reserves - you can think of them as money for banks

Banks use reserves to settle transactions & engage in monetary plumbing operations with each other: reserves can only be used by entities with a CB account

17/

Banks use reserves to settle transactions & engage in monetary plumbing operations with each other: reserves can only be used by entities with a CB account

17/

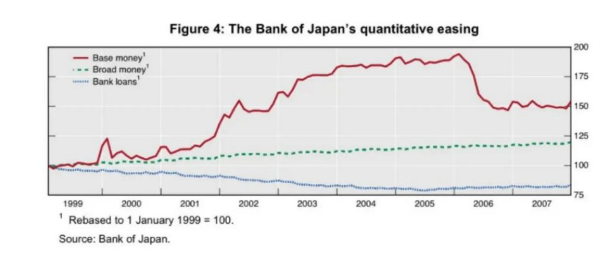

Bank reserves (red) doubled (!) in 5 years as the BoJ went on with QE, and yet bank loans (blue) shrank by 25% in the same period.

With double the amount of reserves, banks lent less.

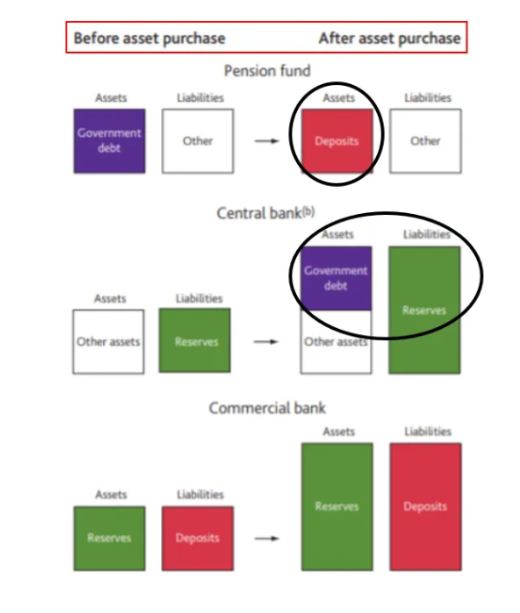

What if the Central Bank does QE with a pension fund instead?

20/

With double the amount of reserves, banks lent less.

What if the Central Bank does QE with a pension fund instead?

20/

Bank deposits held by non-banks financial institutions are financial-sector money.

Not real-economy money.

In short: QE never prints real-economy money, regardless of the recipient (banks or non-banks).

QE only prints financial-sector money = bank reserves.

22/

Not real-economy money.

In short: QE never prints real-economy money, regardless of the recipient (banks or non-banks).

QE only prints financial-sector money = bank reserves.

22/

Conclusions

All they told you about money printing is wrong.

Our monetary system runs on 2 different forms of money: real-economy and financial-sector money.

Governments and banks print real-economy money.

Central Banks print financial-sector money.

23/

All they told you about money printing is wrong.

Our monetary system runs on 2 different forms of money: real-economy and financial-sector money.

Governments and banks print real-economy money.

Central Banks print financial-sector money.

23/

If you enjoyed the thread, head on TheMacroCompass.substack.com for more educational material.

It's free.

Enjoy the rest of your weekend!

24/24

It's free.

Enjoy the rest of your weekend!

24/24

Loading suggestions...