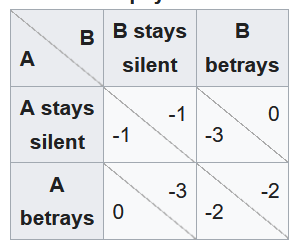

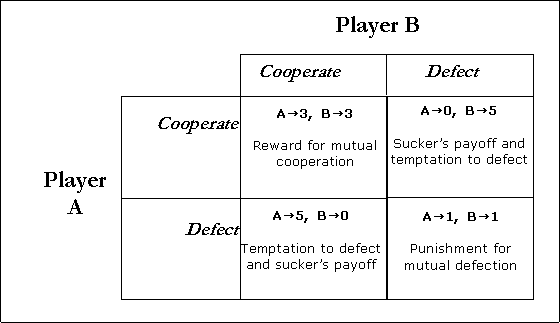

Indeed, the application of the Prisoner's Dilemma was sufficiently prominent by the early 1970s that Glenn Snyder wrote an @ISQ_Jrnl piece in 1971 on its use.

academic.oup.com

academic.oup.com

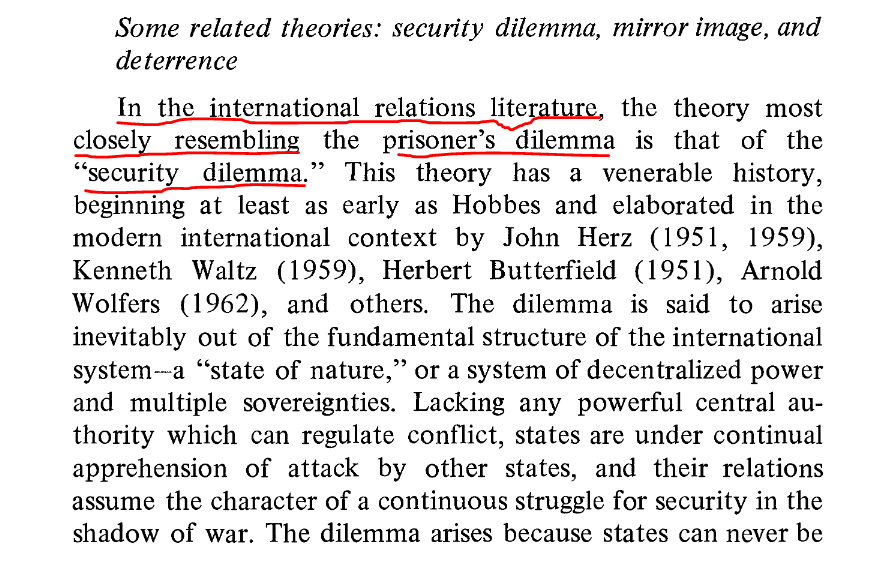

Snyder's paper cites some work by Bob Jervis. That's important, because Jervis' later paper, his 1978 @World_Pol article, became a "go to" cite for using the prisoner's dilemma to depict the difficulties of international cooperation.

cambridge.org

cambridge.org

Shortly after Jervis published his work, another Bob, Bob Axelrod, published a piece in @ScienceMagazine about how cooperation may not be as hard as the prisoner's dilemma suggests.

science.org

science.org

Specifically, if the game is repeated, then the parties could have an incentive to cooperate (i.e. knowing that I may need your cooperation in the future gives me an incentive to not cheat now).

Jervis fleshed out this idea in his 1984 book.

amazon.com

Jervis fleshed out this idea in his 1984 book.

amazon.com

While Axelrod's work became the major cite in international relations regarding the power of repeated games, it's building on a point made much earlier (in a 1970 JCR article) by Martin Shubik.

journals.sagepub.com

journals.sagepub.com

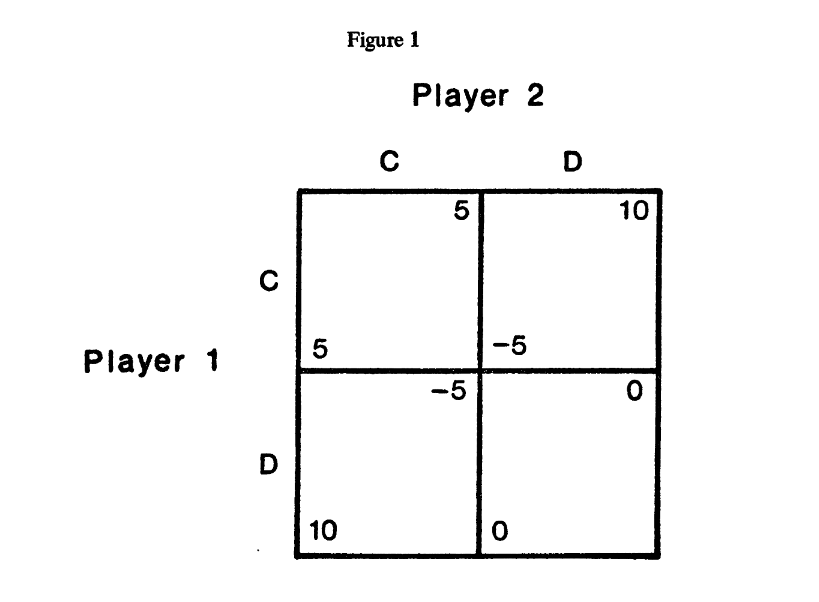

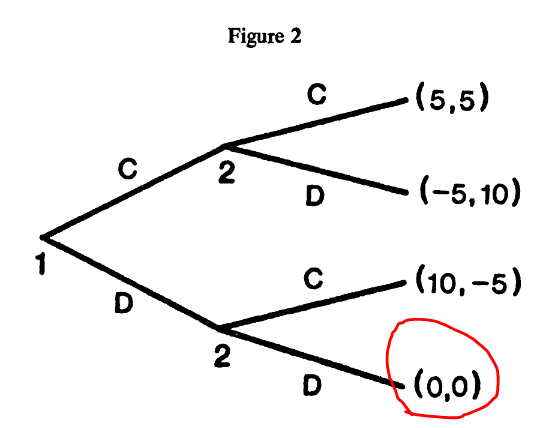

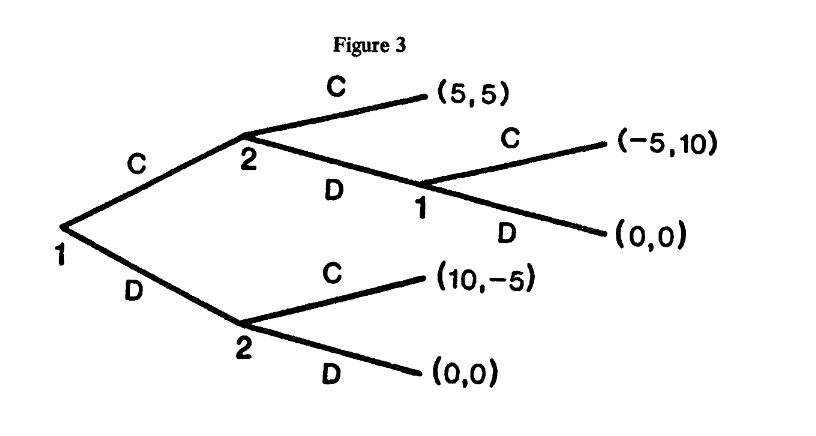

But Wagner then poses a key question: "why must the end of the tree look like that?"

Wagner makes clear that this is NOT the same as simply iterating the game. Instead, the game is different, but more accurate.

Stated differently, iterated games hold that cooperation occurs because I worry about what will happen with THE NEXT arms control treaty.

Wagner's game holds that cooperation occurs because I can observe what happens with THIS arms control treaty.

Wagner's game holds that cooperation occurs because I can observe what happens with THIS arms control treaty.

In other words, compliance with New START isn't about fear over missing out on New New START, it's possible because the sides know the other will see if it cheated (which, by the way, is what happened).

nytimes.com

nytimes.com

Same with trade treaties: states cooperate with them, not because they hope to gain the NEXT trade treaty, but because they know that non-compliance can be observed.

piie.com

piie.com

Wagner's simple yet underappreciated proposal -- adding a branch to the Prisoner's Dilemma game -- more correctly & usefully depicts of the challenges of & opportunities for cooperation.

It, not PD, SHOULD be the standard game theoretic model of international politics.

[END]

It, not PD, SHOULD be the standard game theoretic model of international politics.

[END]

Loading suggestions...