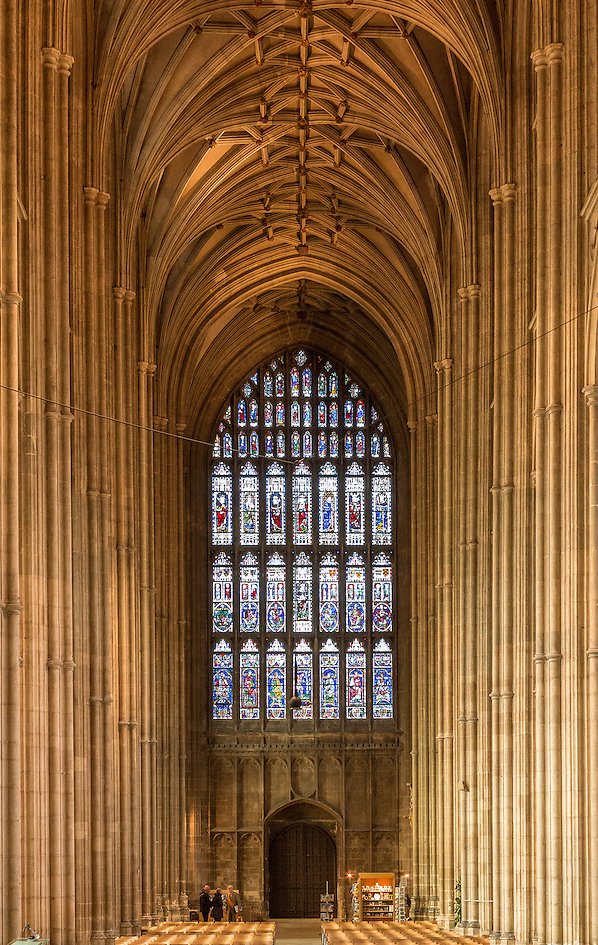

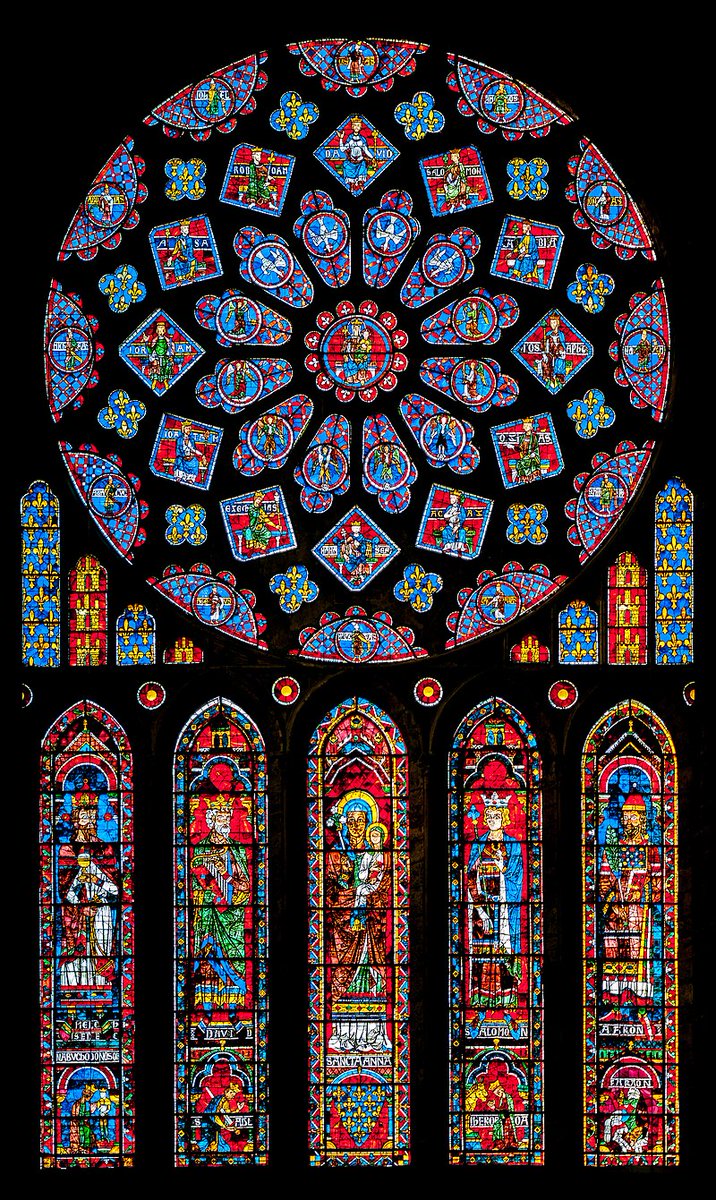

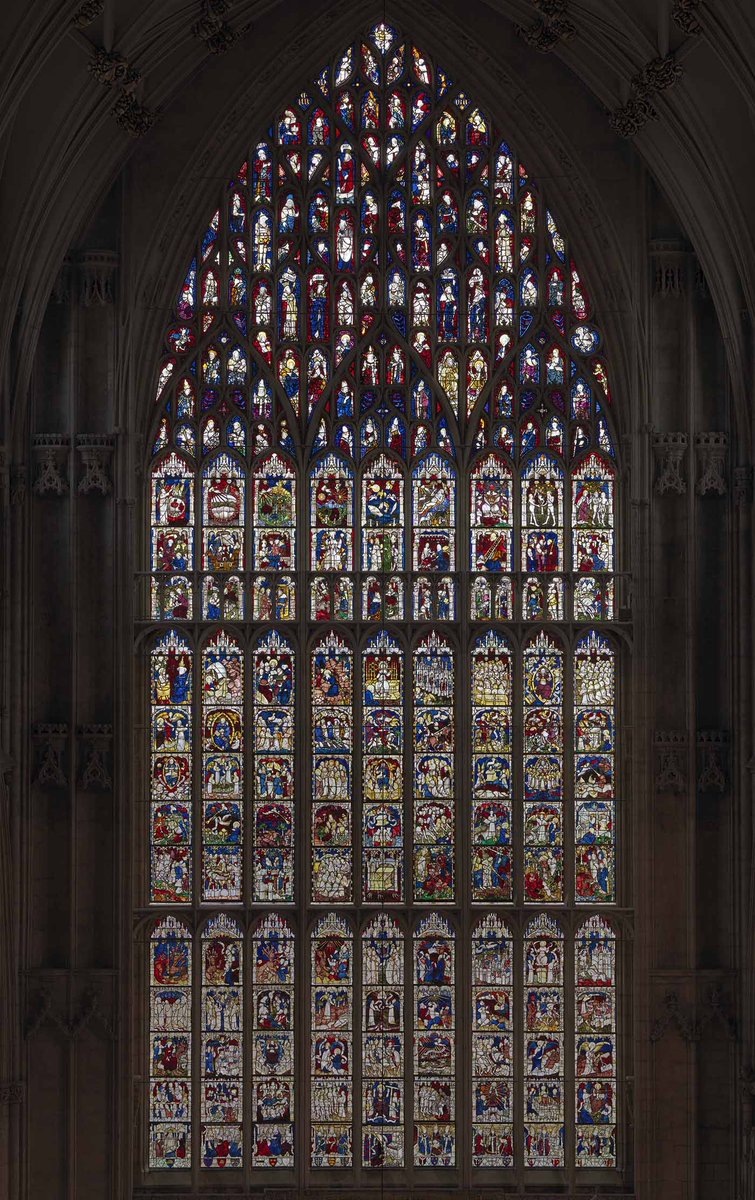

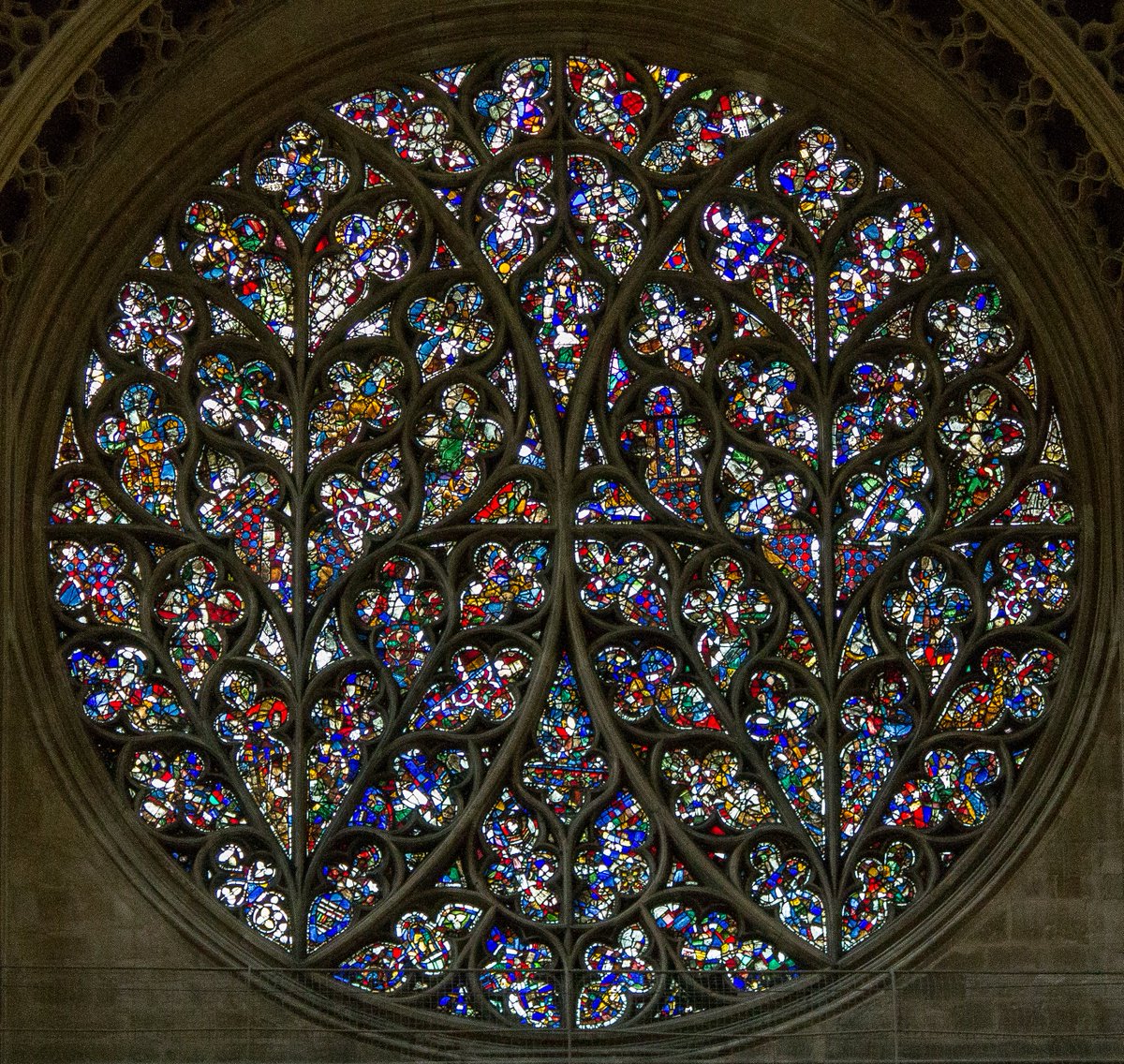

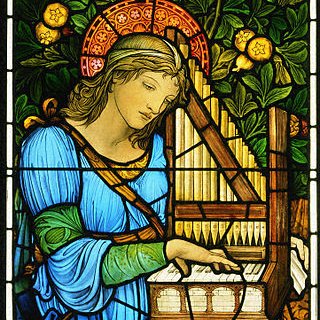

But most beautiful about Medieval stained glass was its mix of simplicity and imperfection; an imperfection which produced more powerful & varied effects of colour and light.

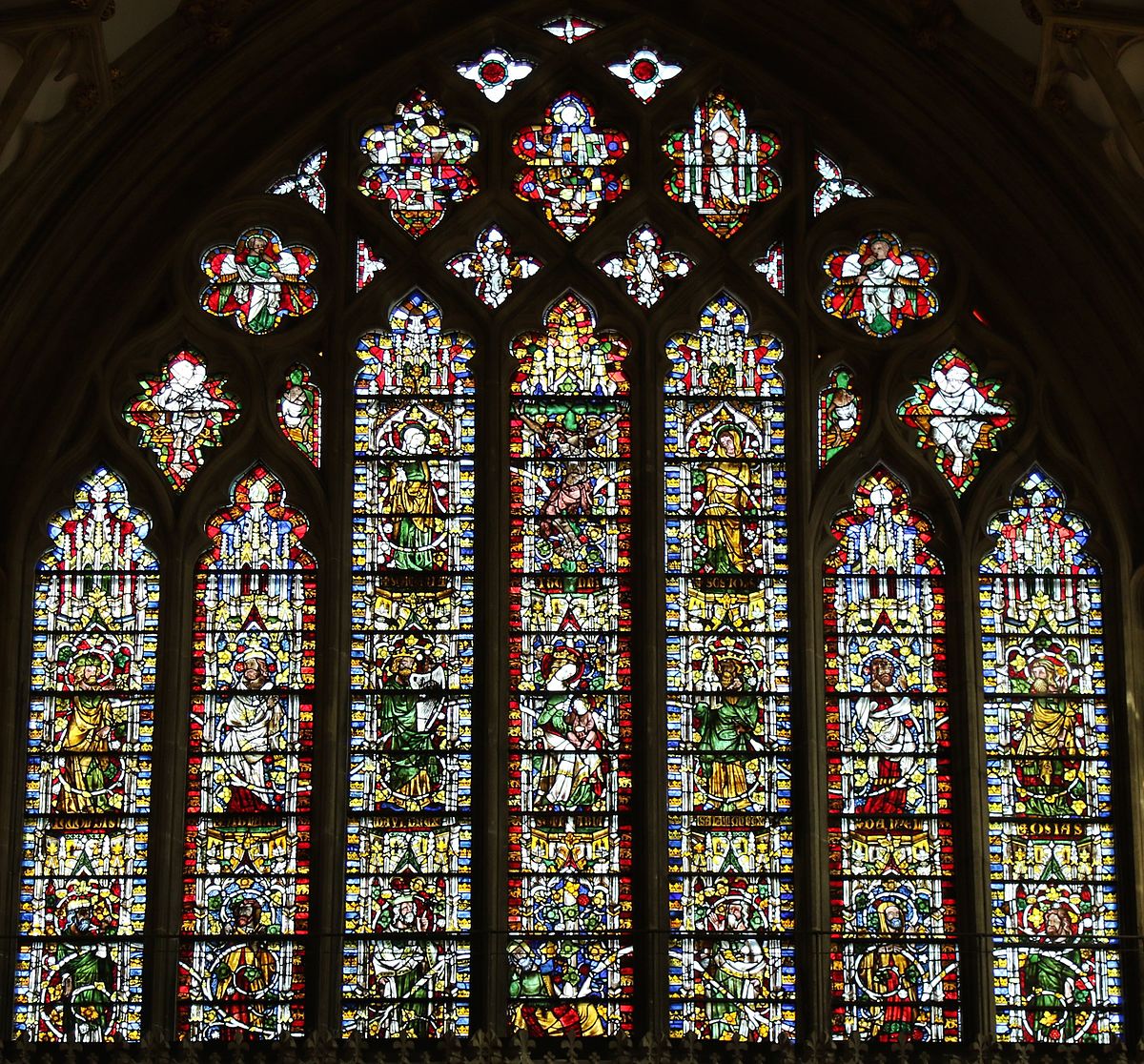

Perhaps all that innovation and realism refined the majesty out of stained glass.

Perhaps all that innovation and realism refined the majesty out of stained glass.

Loading suggestions...