Xiongnu- Huns- Hungarians

The most notable Roman writer to describe the Huns in some detail was the historian and soldier Ammianus Marcellinus (330-395), though his descriptions were flavored with a heavy dose of bias and ethnocentrism.

Ammianus, however, praised the Huns' equestrian skills, and attributed those skills to a life spent in the saddle.

This westward movement of Hunnish peoples initiated what historians call the "Great Migration" — a mass movement of Germanic peoples into Roman territory.

It was the Huns who drove the Goths, Vandals and Alans west, all nations that would swoop down on Roman provinces like ravenous predatory birds. They were to dismember the Empire and feed upon its decaying carcass after its fall. razib.substack.com

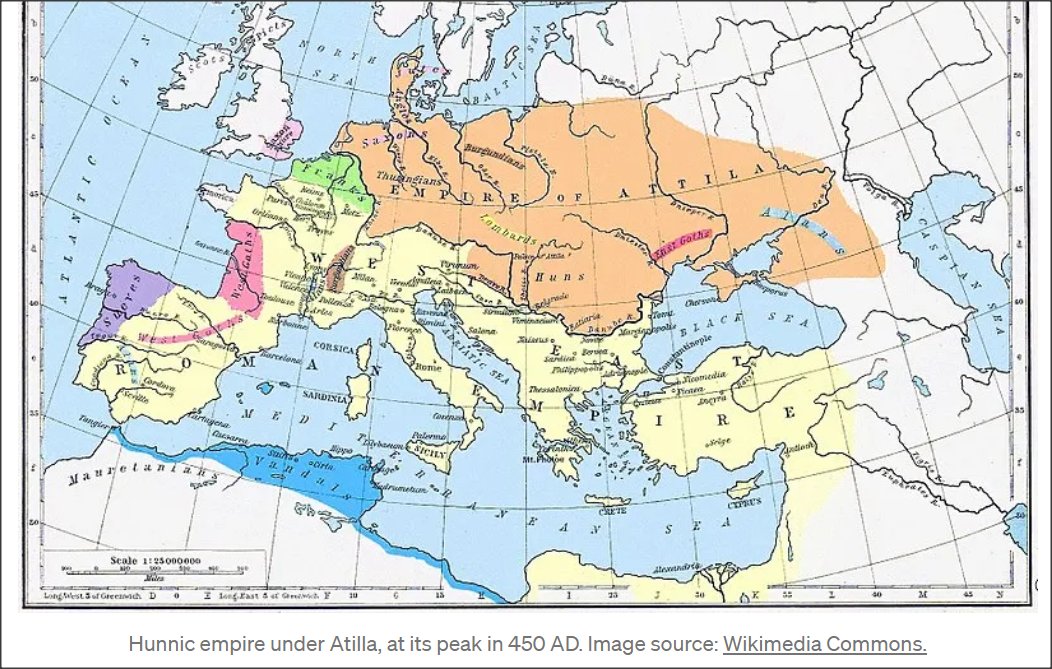

As the Huns spread westward, they assimilated several Eurasian tribes, including the Alans, who were Iranic. Many Germanic tribes, such as the Gepids, were also among Atilla’s forces.

Sometimes known as the Gepidae to Roman writers, they had followed the Goths on their slow migration south-eastwards, ending up in the Pannonian basin where they formed a short-lived tribal kingdom known as Gepidia.

Between the Dniester and the Danube, the Tervingi, later known as the Visigoths, held sway. Their leader, Athanaric, was outmaneuvered by the Huns, who forded the Dniester at night and struck at the Tervingi from behind.

The Huns raided the Eastern Roman Empire in 422 at a time when it was again at war with the Sassanids.

In the Western Roman Empire, Aetius was preoccupied with the Visigoths and Burgundians in Gaul.

In the East, relations between the Roman Empire and Attila deteriorated. Tribute had not been paid, refugees not returned and the bishop of Margus had plundered Scythian tombs in Hun territory.

Attila murdered his brother Bleda in or around 445. Under the sole rule of Attila the power of the Huns reached all time highs.

Attila had numerous wives and sons, but he had left no provisions for his succession. Attila’s sons, Ellac, Dengizich, and Ernakh, divided the empire.

The Hun vassals saw Attila’s death as an opportunity to rid themselves of their overlords. Led by Ardaric the Gepid, the Gepids and Goths shattered the Hun supremacy in an epic battle by the Nedao (Nedava) River in 454 or 455.

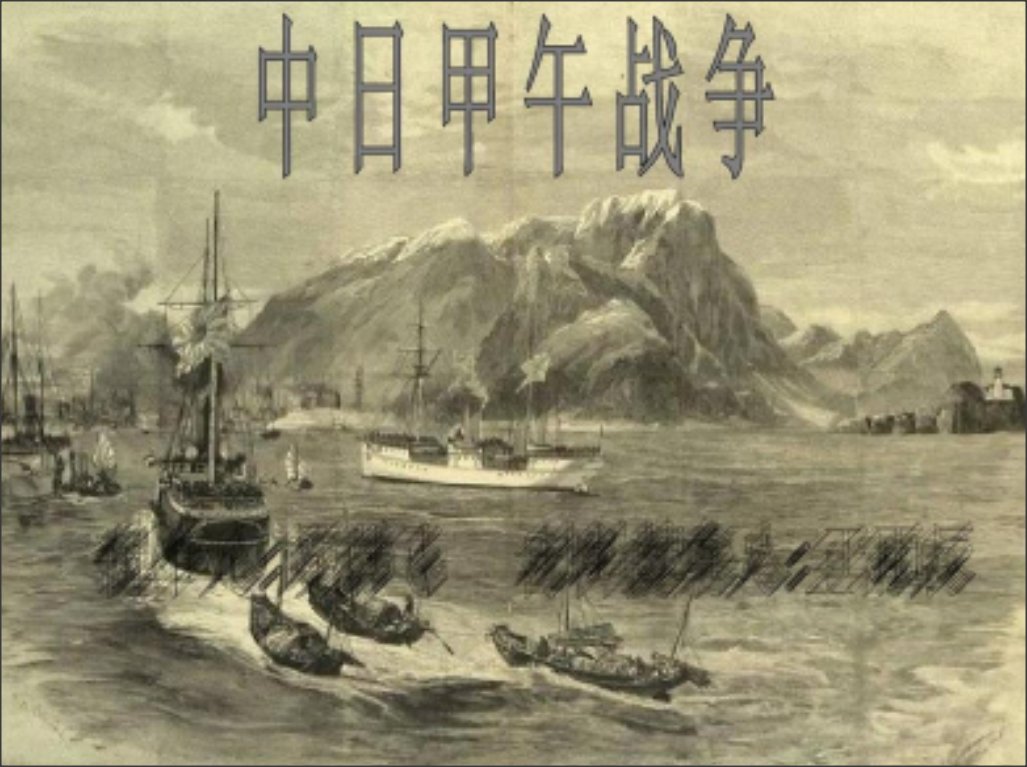

In 1896 and 1897, Britain, the United States and the German Reich each dispatched a commission to East Asia to study the local economic conditions; in all three cases, their reports emphasized the tangible benefits rather than the potential dangers of Western economic engagement.

Resistance to Chinese immigration forced US political institutions to react by passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which severely curtailed Chinese labor migration.

Local administrators and landowners' associations in West Prussia repeatedly suggested recruiting Chinese agricultural laborers in the 1890s and 1900s, sparking a controversy in which social and cultural stereotypes were mustered against the importation of Chinese labor.

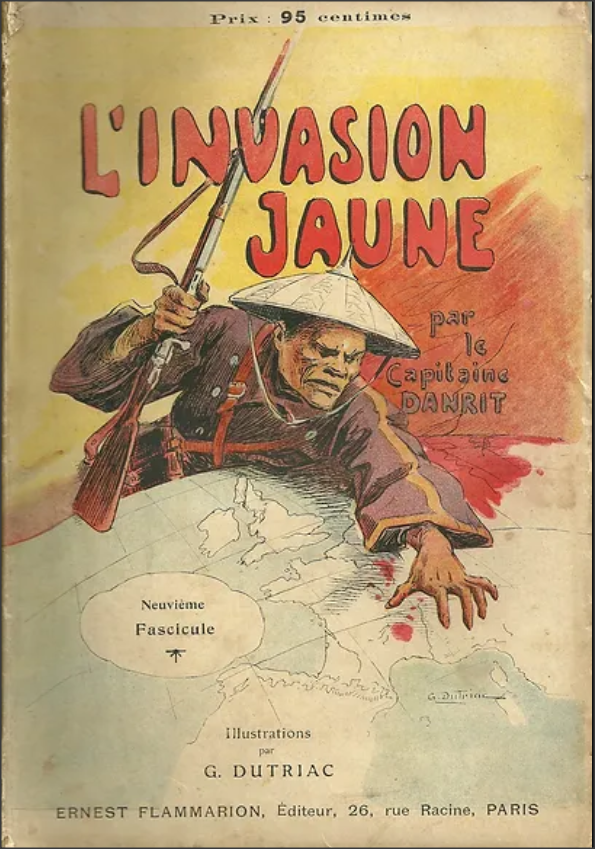

Besides issues of economic development, there was also a political dimension to the Yellow Peril, as East Asia was primarily perceived as a political and military threat to Europe and North America.

The German leader instrumentalized the idea of a Yellow Peril as part of a diplomatic diversion, to redirect the Russian gaze away from the Reich's eastern border and towards East Asia.

However, the impact of the Kaiser's intervention went far beyond its immediate context.

However, the impact of the Kaiser's intervention went far beyond its immediate context.

After the relief of Beijing , with more correspondents on the ground and more comprehensive information available through detailed letters rather than sparse telegrams, the focus of attention shifted to the conduct of the Allied troops in China.

The atrocities committed by troops of the Western powers gave rise to a controversial debate about the merits and shortcomings of the multinational intervention and, more generally, of the transnational informal empire in China.

The German missionary Martin Maier (1866 – 1954) lumped Japan and China together, in part because he attributed the Yellow Peril to racial differences as well as hatred of the "Western" foreigners in both countries.

Further reading,

The Boxer War: Media and Memory of an Imperialist Intervention

By Thoralf Klein

books.google.com

The Boxer War: Media and Memory of an Imperialist Intervention

By Thoralf Klein

books.google.com

Loading suggestions...