In the previous installment (PHYS001), we learnt all about nuclear reactions and the energy produced by them.

We also spoke briefly about one chemical reaction and energies associated with it.

...But we never discussed what energy *is*. [vsauce music]

We also spoke briefly about one chemical reaction and energies associated with it.

...But we never discussed what energy *is*. [vsauce music]

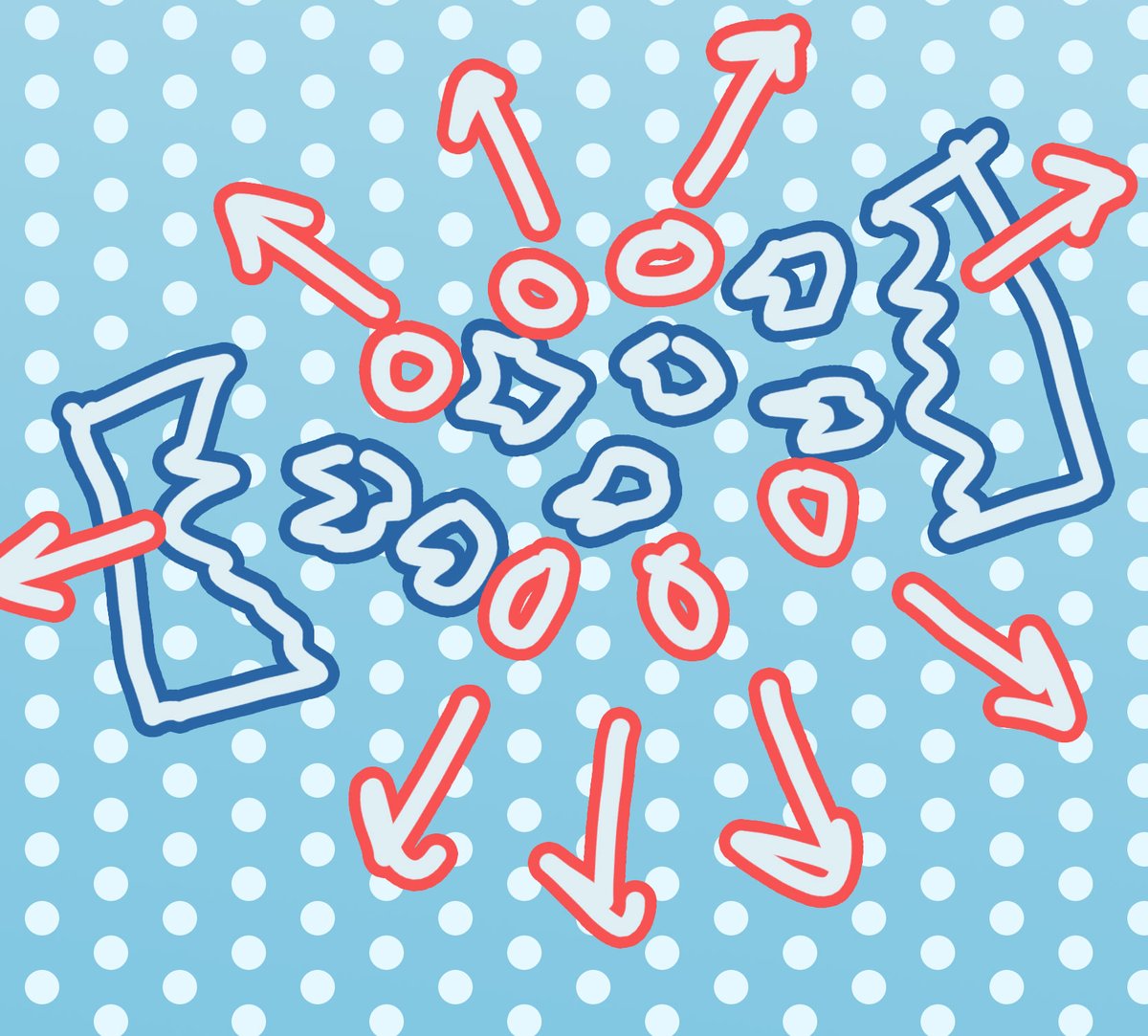

But there's one other conservation rule we have to take care of, the conservation of momentum!

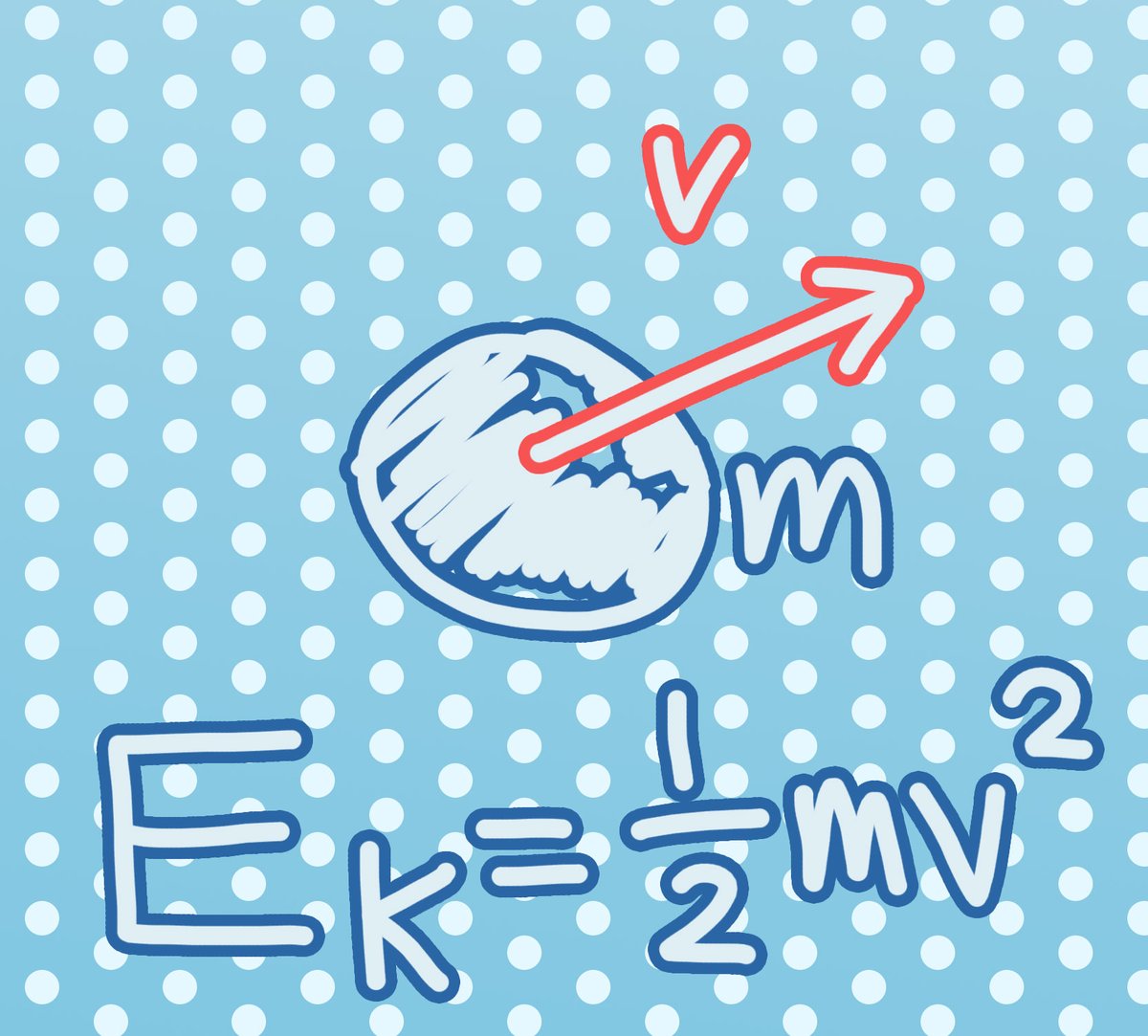

What is momentum? Well, simply put it's the "weight of your motion", specifically, the mass of a particle multiplied by it's velocity (speed v).

Try it at home:

youtu.be

What is momentum? Well, simply put it's the "weight of your motion", specifically, the mass of a particle multiplied by it's velocity (speed v).

Try it at home:

youtu.be

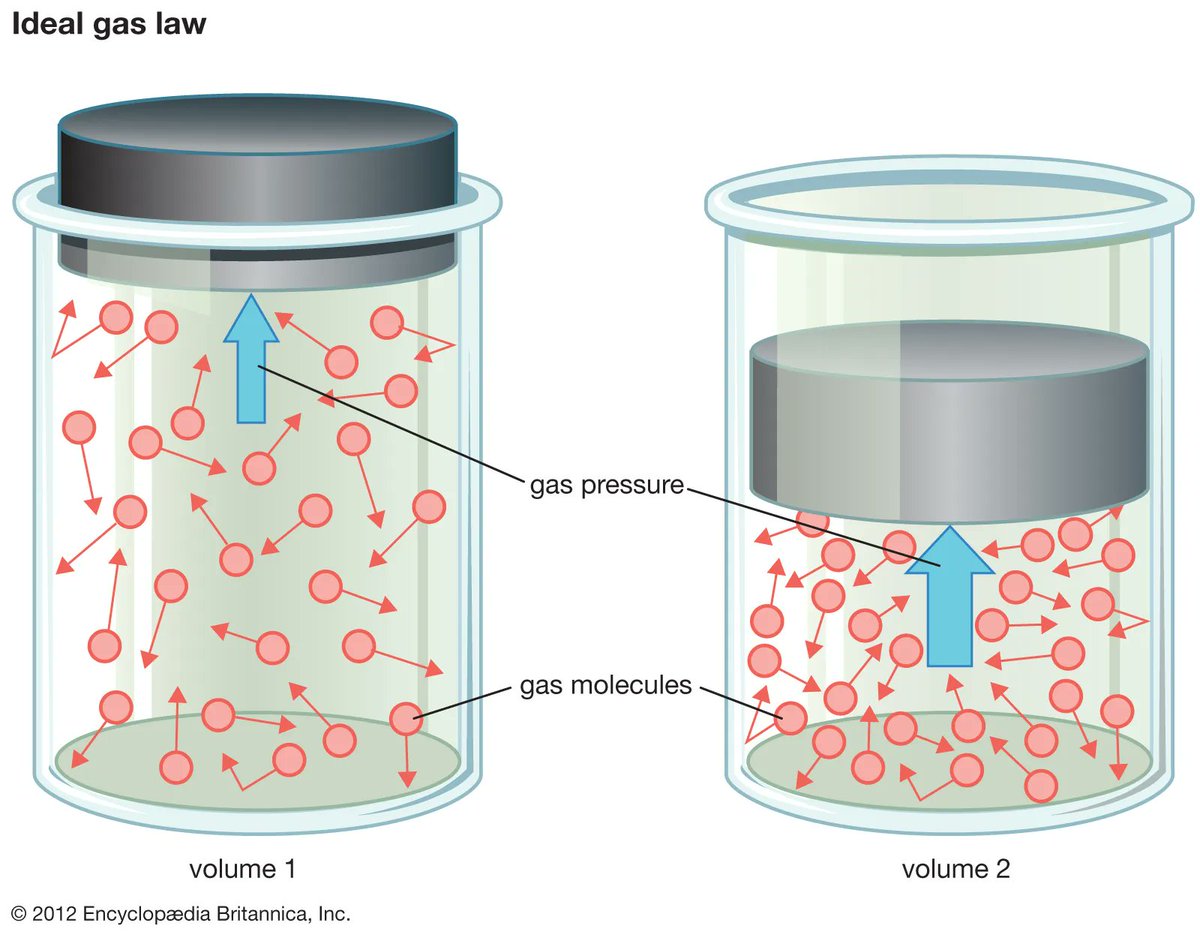

You see, dealing with individual particles is kind of impossible. Even a gram of flour contains more particles inside than you can practically simulate (let alone track) on a computer in a lifetime.

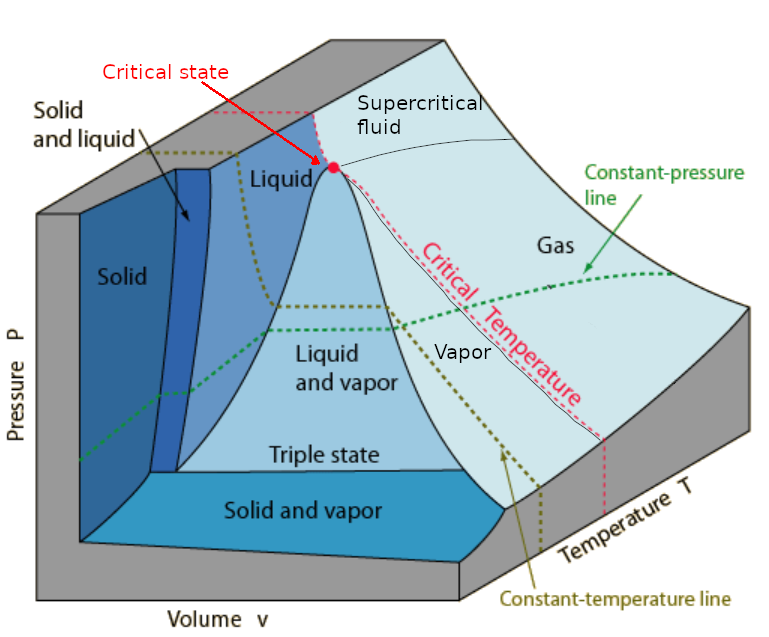

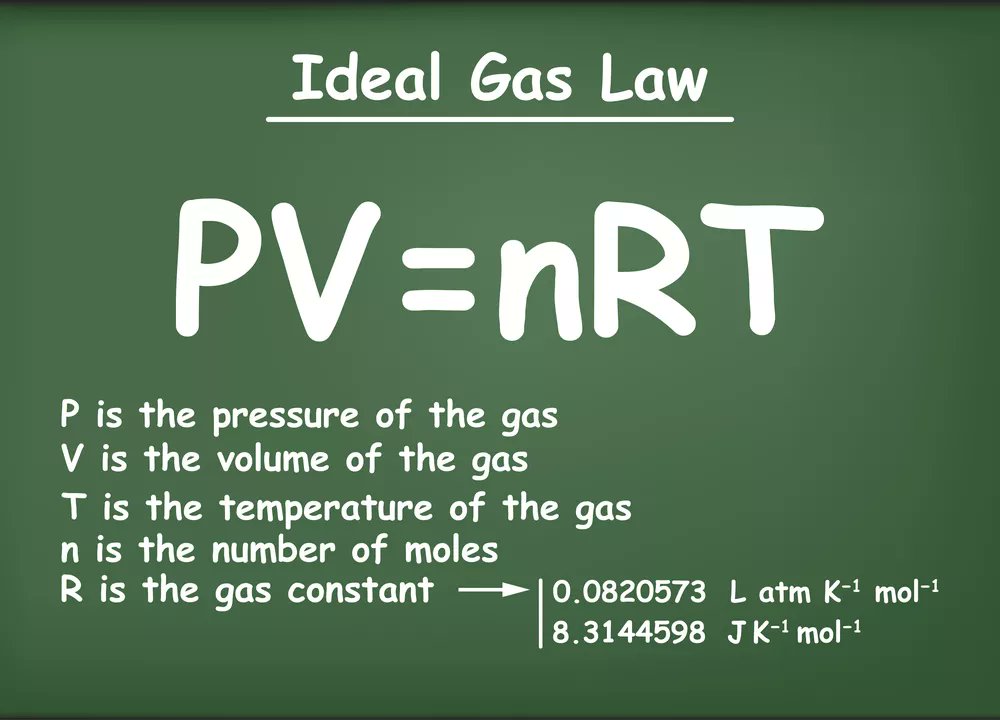

We need some new abstractions:

Volume.

Pressure.

Temperature.

We need some new abstractions:

Volume.

Pressure.

Temperature.

The more particles of a gas in a given volume the more the pressure.

But there's also the temperature to consider!

The temperature is the average kinetic energy in a state. Most of this would be in things like vibrational/rotational/excitement but contained energy. Complicated...

But there's also the temperature to consider!

The temperature is the average kinetic energy in a state. Most of this would be in things like vibrational/rotational/excitement but contained energy. Complicated...

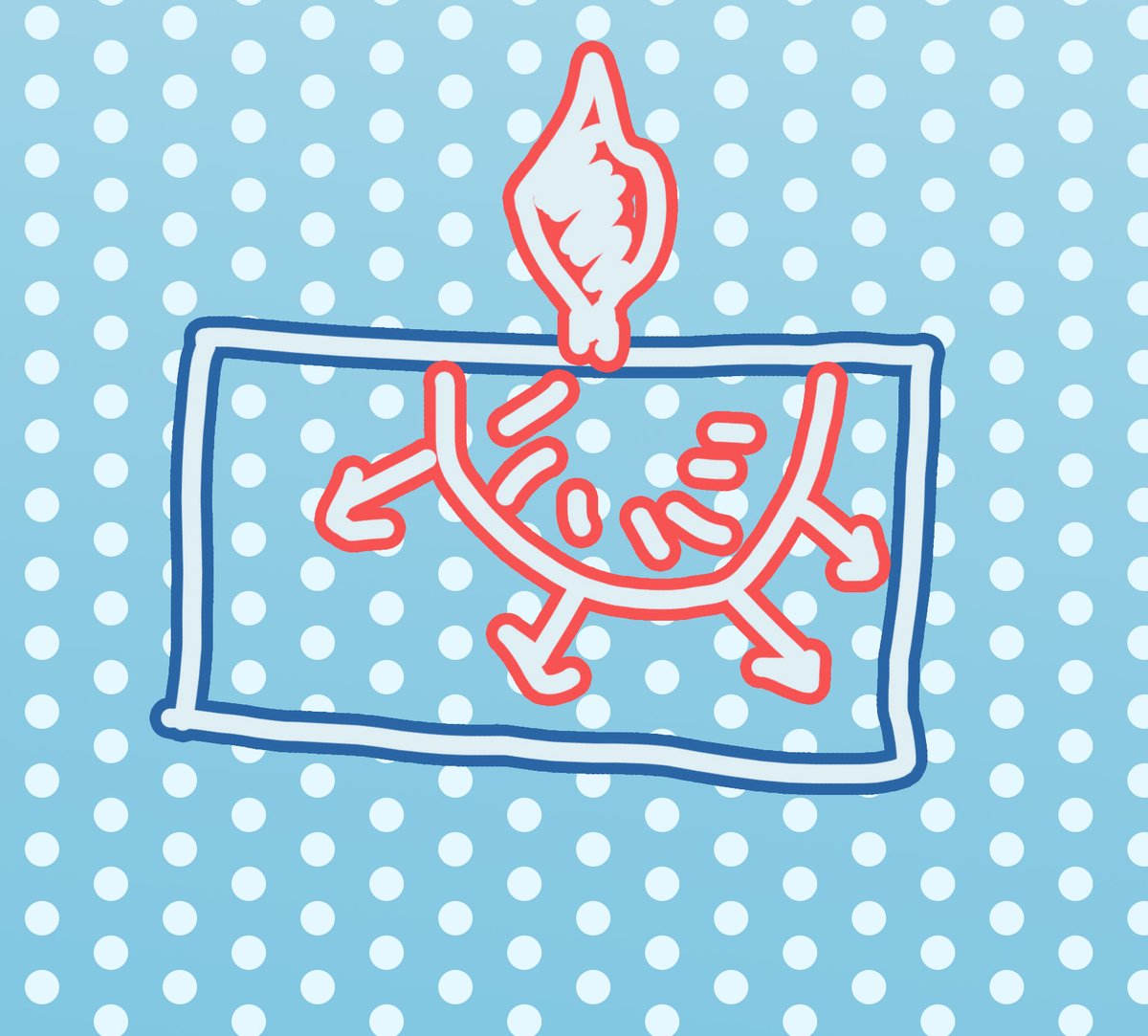

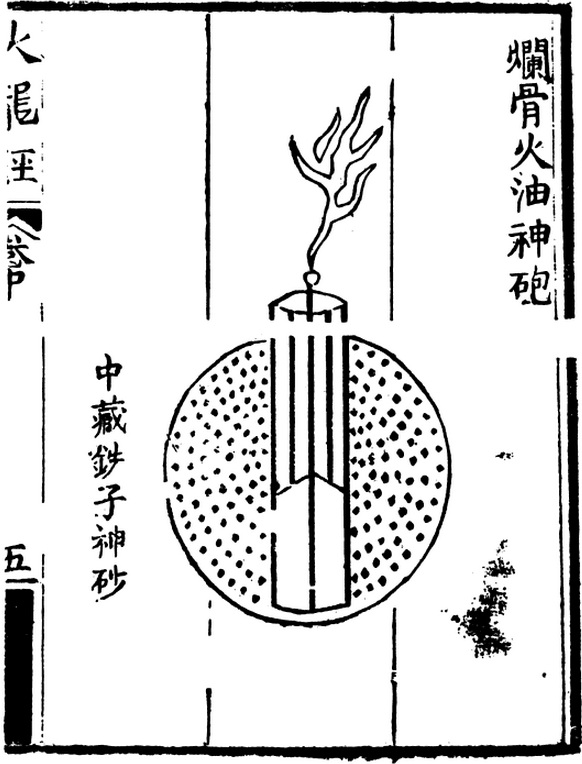

In this case we have an incomplete explosion.

We allowed the volume of the primitive explosive device to change to the point where it broke apart, and not all the material contributed to the chain reaction, or it diffused over an ineffective area.

This is a basic blast device.

We allowed the volume of the primitive explosive device to change to the point where it broke apart, and not all the material contributed to the chain reaction, or it diffused over an ineffective area.

This is a basic blast device.

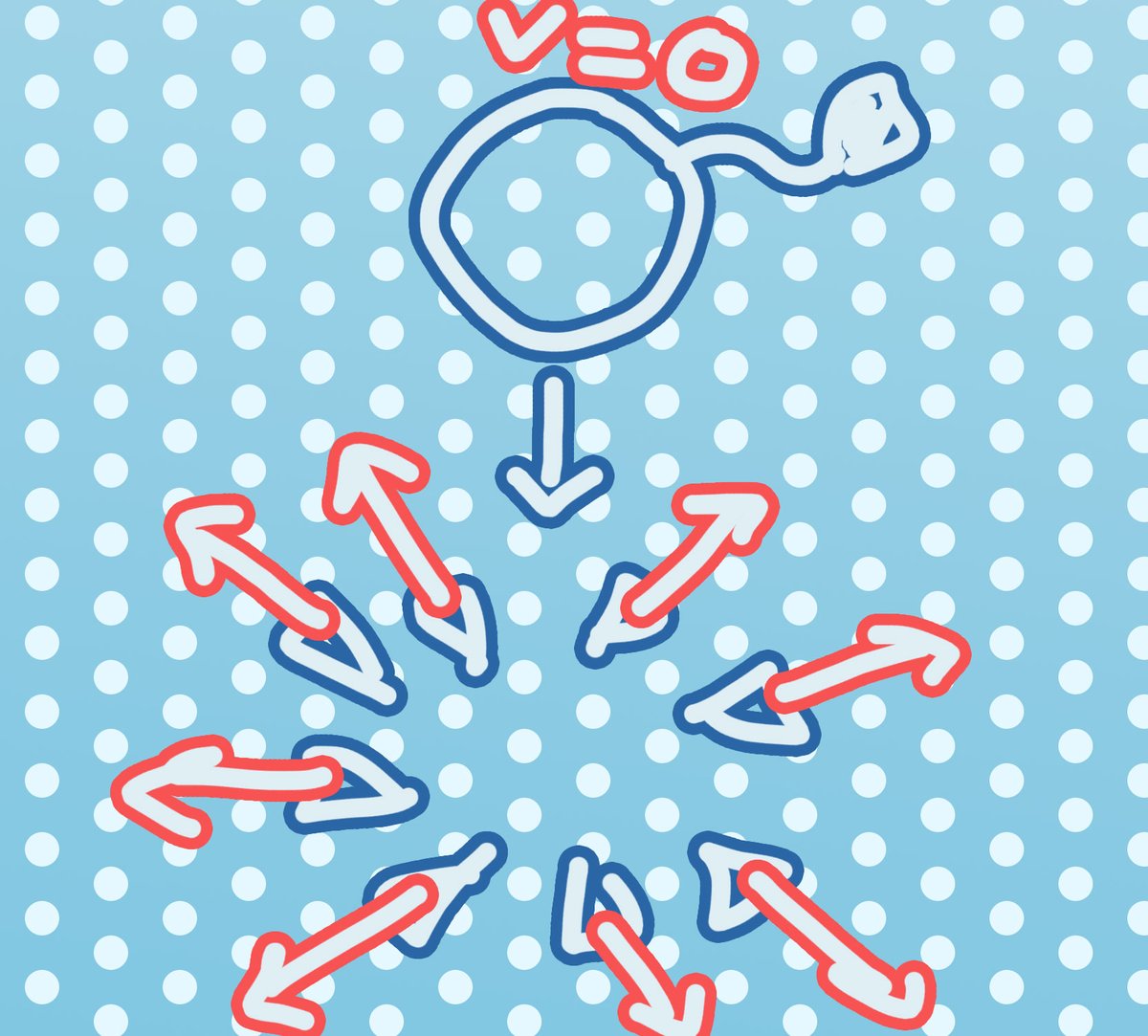

Aside: Notice the white smoke that fills the space during an explosive event. This is the gas we spoke of before exploding out in all directions! It's a very hot gas and creates a shockwave that can kill you instantly if you're in the kill zone, and damages everything.

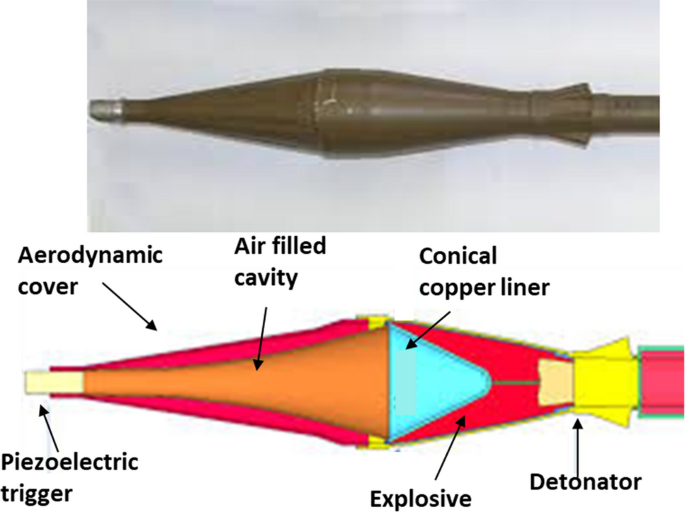

A shaped charge, introduces an asymmetry to drive metal to high speeds and temperature, taking at most half of that momentum and using it to blast through some thick armor from the sheer speed and temperature of the penetrator.

youtube.com

youtube.com

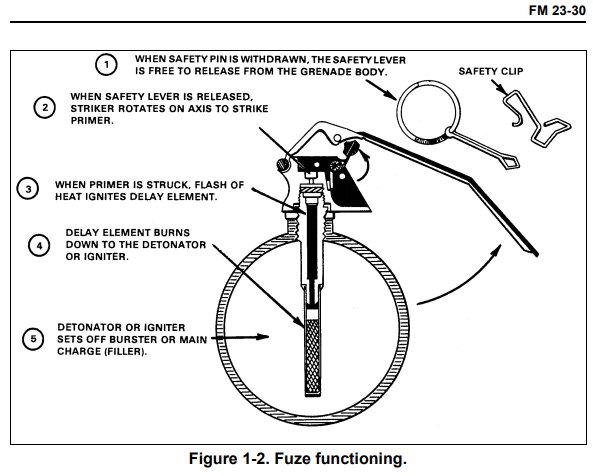

It's important to discuss the fuzing as well, these have gotten very advanced over the years. It is sad that the impact fuze won the US WWII, not the nuclear bomb. I do agree.

Having this circuit survive the extreme accelerations involved isn't simple!

youtu.be

Having this circuit survive the extreme accelerations involved isn't simple!

youtu.be

Thanks to advances in technology, it became possible to create a new kind of "thermobaric bomb", that uses a delicate primer+timed fuze, and tertiary igniter to first spread fuel around an area and then detonate it all at once to create a deadly shockwave.

youtu.be

youtu.be

Now how far can we scale these bombs up? What's the largest conventional bomb (other than the FOAB which is in its own special category, but still rather "small" at a maximum of 40 ton equivalent TNT).

That designation would go to the M.O.P!

youtube.com

That designation would go to the M.O.P!

youtube.com

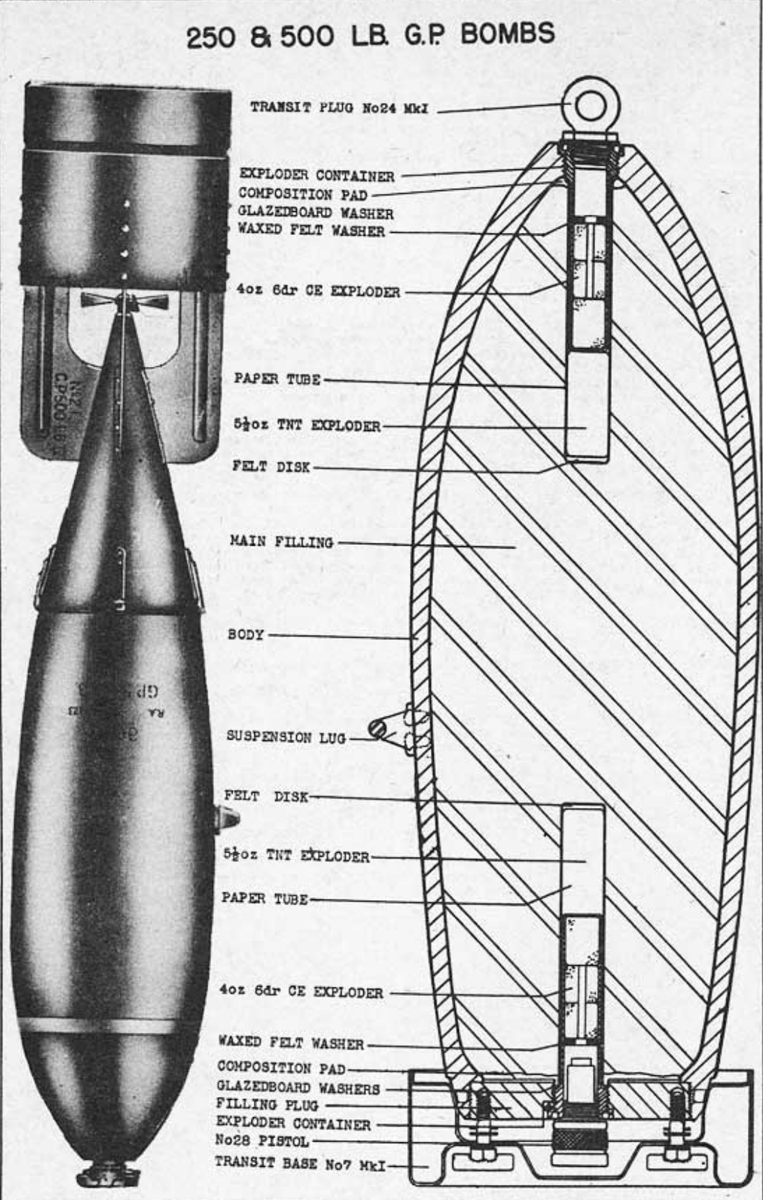

The warhead on the M.O.P contains a 2,400kg explosive, but the bomb itself is 14,000kg.

What gives?

Well you see, in its specific mission, the casing has to be extremely strong. In fact, there is a practical limit with conventional bombs due to the size of the required casing!

What gives?

Well you see, in its specific mission, the casing has to be extremely strong. In fact, there is a practical limit with conventional bombs due to the size of the required casing!

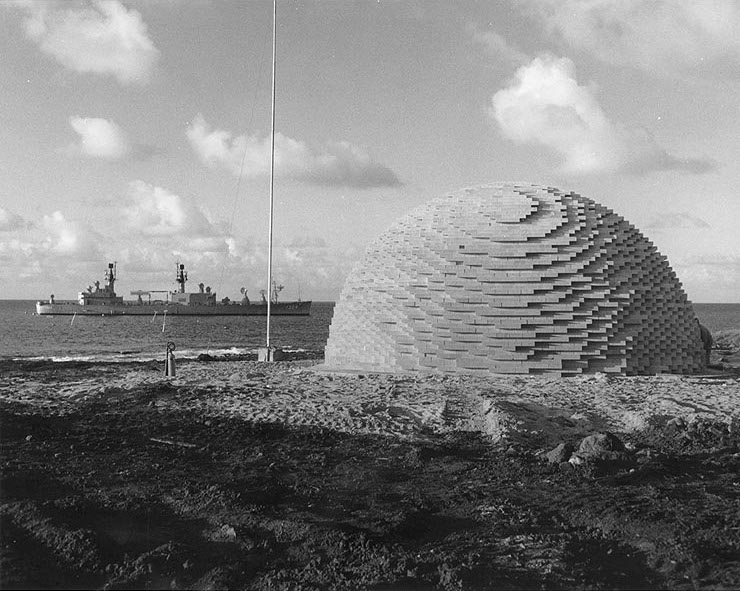

In this test, the US military stacked 500 short-ton explosive charges of TNT in a hemisphere and used some precision electronics to have them detonate all at the same time, faster than what a conventional shockwave would do.

Here's what happened:

youtube.com

Here's what happened:

youtube.com

As you can see, the half kilo ton explosion created a massive shockwave, very similar to that you would see with a low yield nuclear bomb. You see the "mushroom cloud" as well, and most importantly the SYMMETRY of the explosion!

There's a few things you don't see however, and we'll get to that later. But the key point I want you to take from this is the difficulty in producing this symmetric explosion and the deliberation required.

You see, miss the timing, the structure wouldn't explode in unison...

You see, miss the timing, the structure wouldn't explode in unison...

Configure the shape incorrectly? The shockwave will not be symmetric and will begin to cancel itself out, attenuating the explosion in the center or making it directional.

Notice also, a total lack of "stringers"!

youtu.be

Notice also, a total lack of "stringers"!

youtu.be

These stringers are a key tell in an unorganised/non-deliberate depot explosion. They can be caused be a variety of reasons, simply hot fragments and unexploded pieces of ordnances is one reason.

Also note that a shockwave is visible thanks only to water vapor in this case.

Also note that a shockwave is visible thanks only to water vapor in this case.

I should say in some cases, it uses chemistry (such as this)

Said that the proximity fuze*

Loading suggestions...