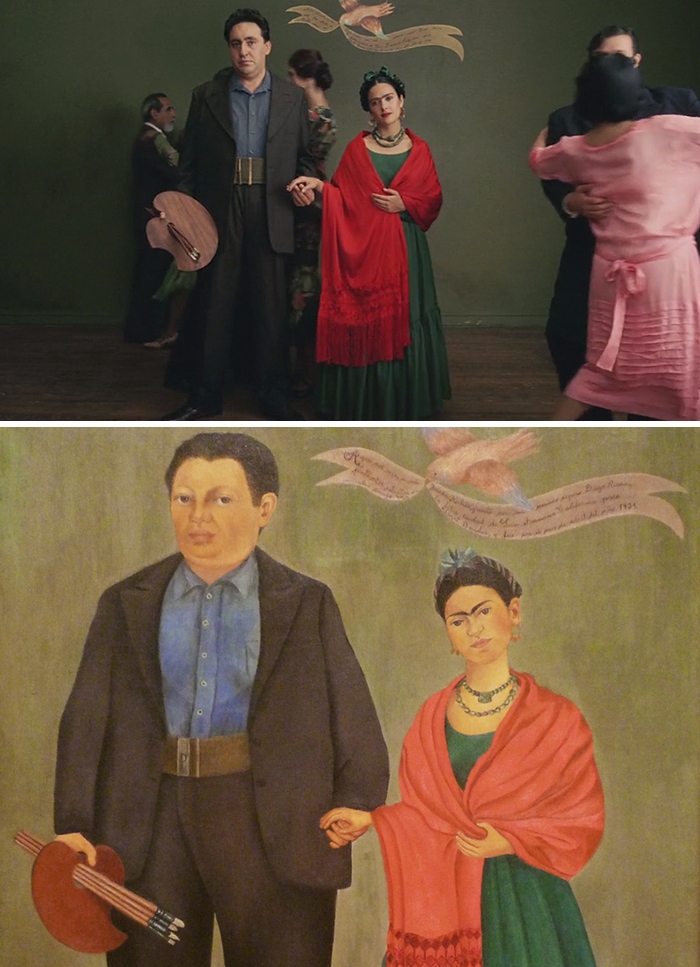

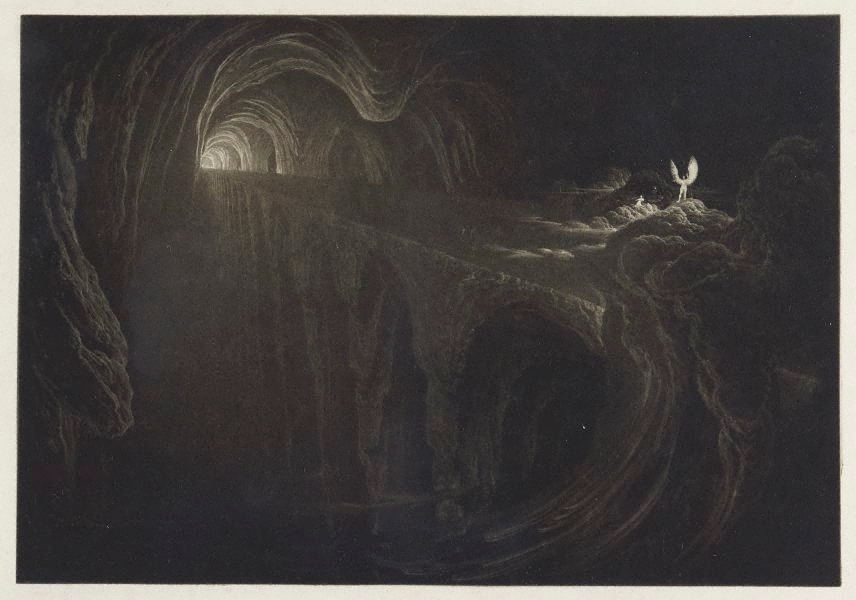

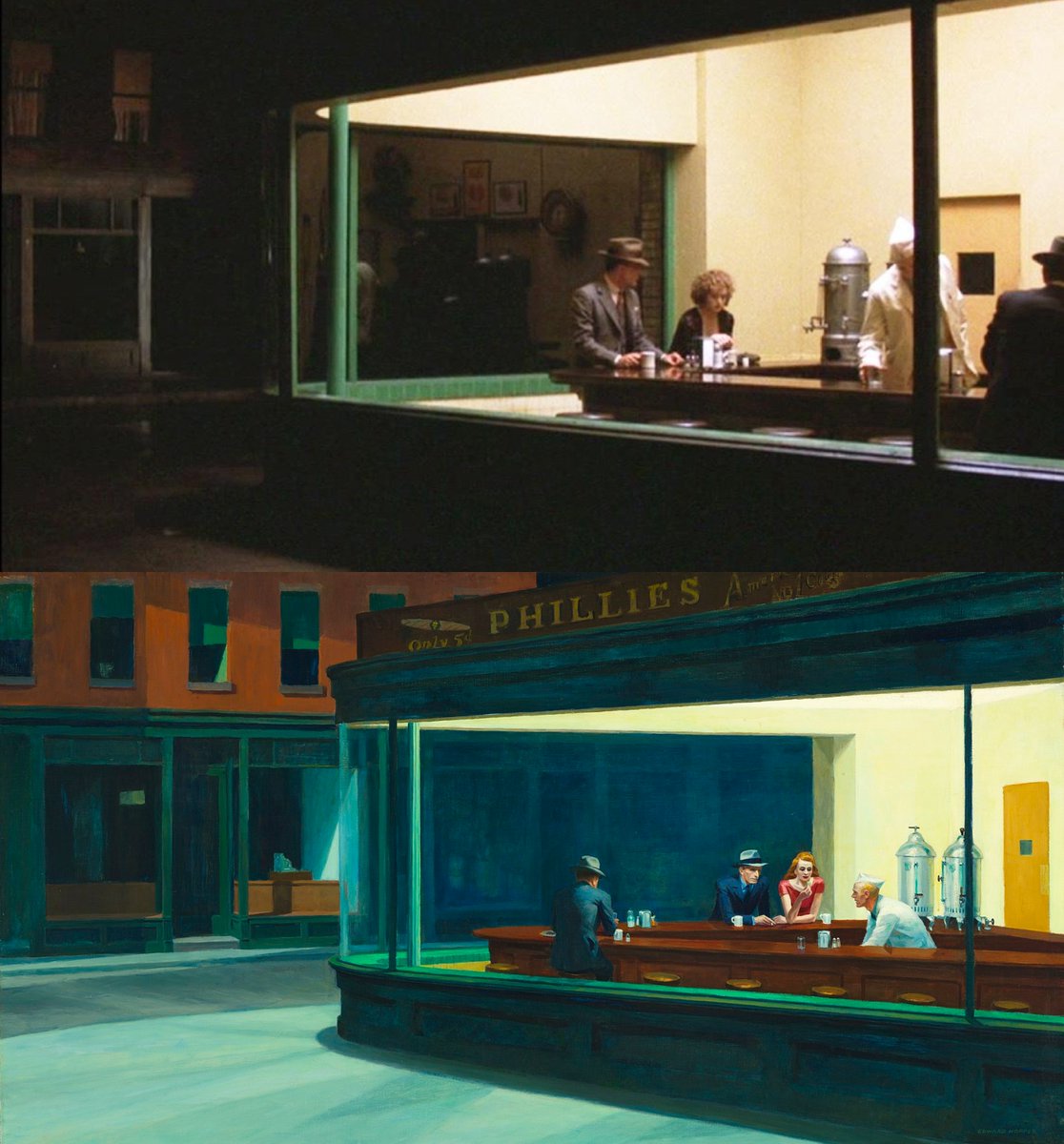

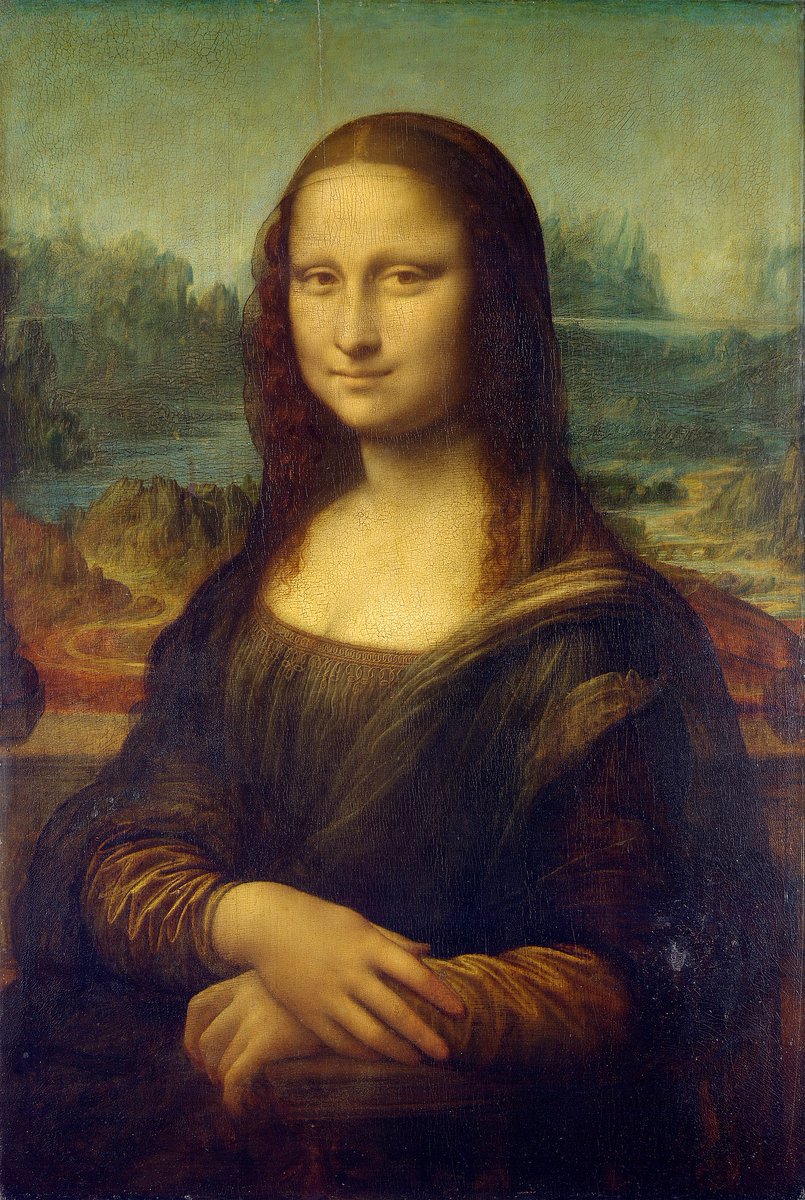

The examples go on and on... but why? Is it just a gimmick, or is it pastiche, or even some sort of artistic easter egg?

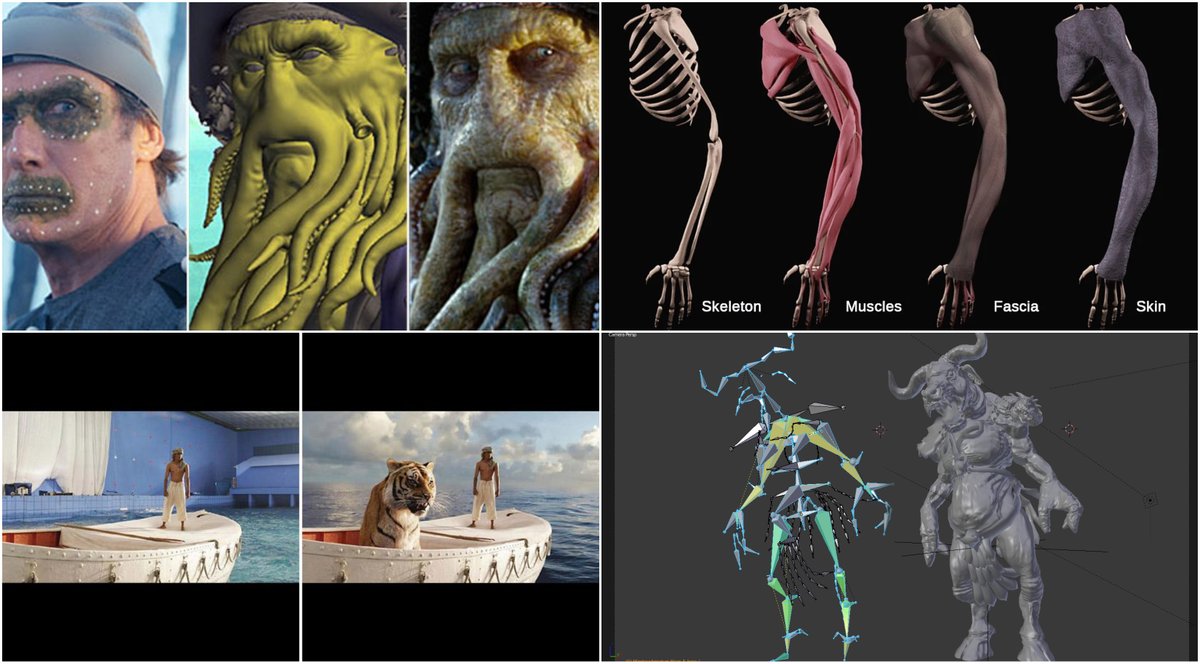

That might be the case on occasion, but more often than not directors have a very good reason to draw on art: cinema and painting have lots in common.

That might be the case on occasion, but more often than not directors have a very good reason to draw on art: cinema and painting have lots in common.

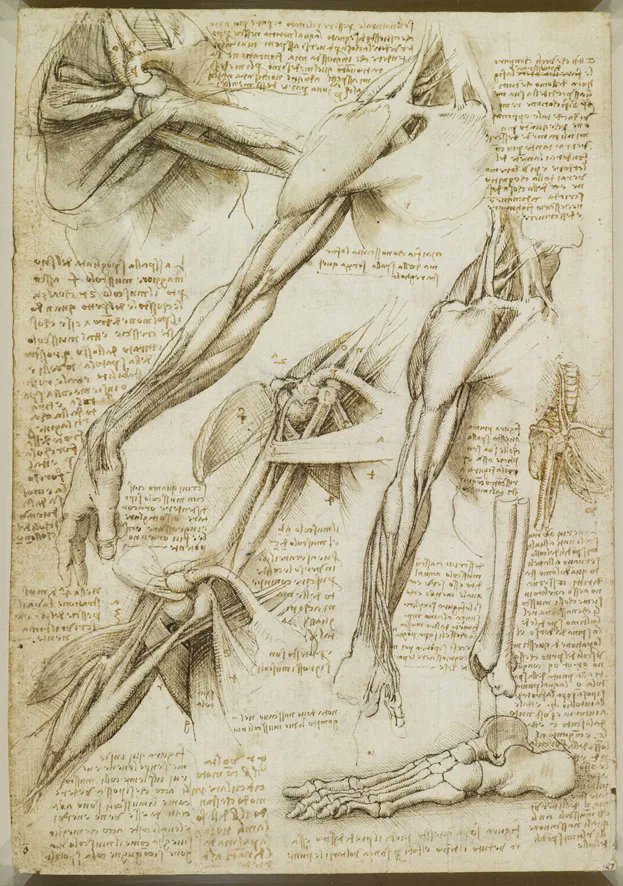

But there's more to this. Many technical elements of painting apply directly to film-making.

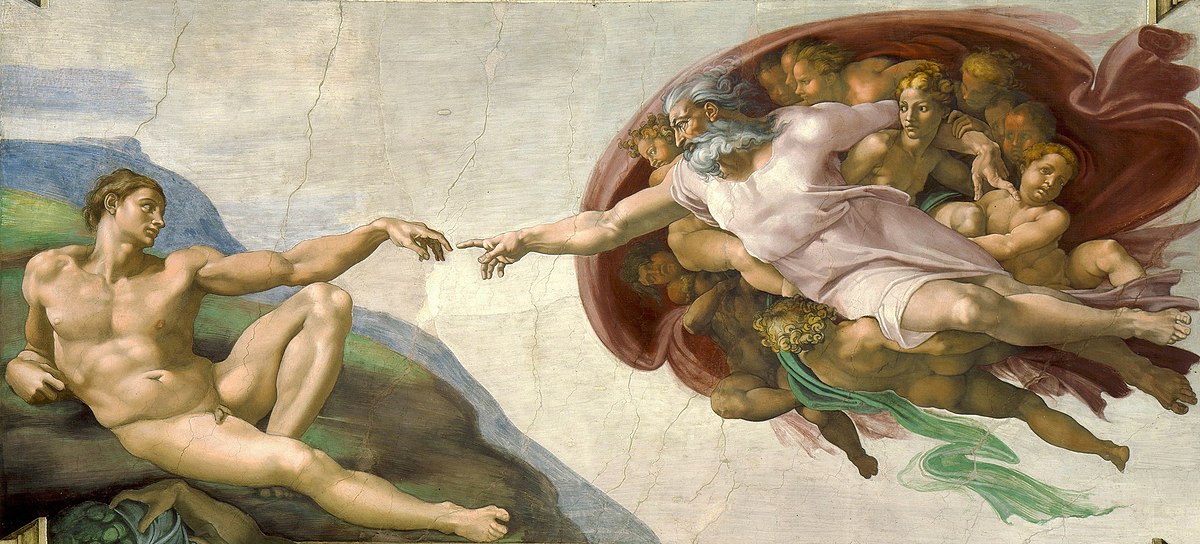

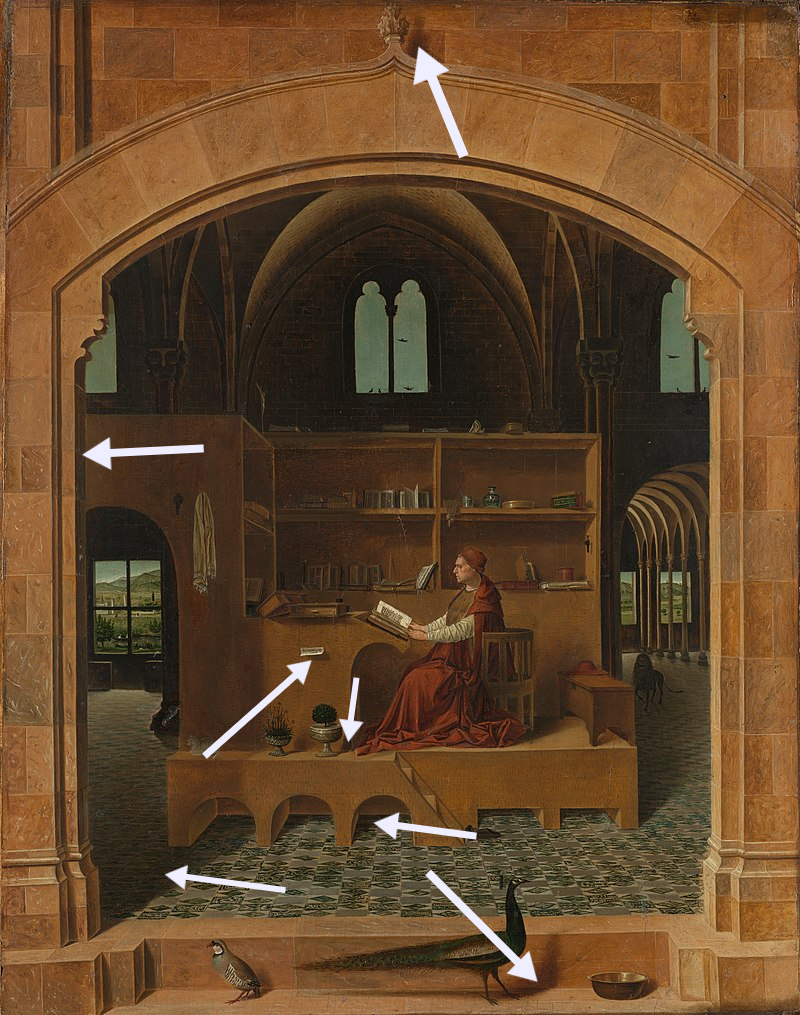

Take composition, which is where and how each element of an image is positioned in relation to every other.

Why is each thing where it is, and why is it that size, shape, and colour?

Take composition, which is where and how each element of an image is positioned in relation to every other.

Why is each thing where it is, and why is it that size, shape, and colour?

Loading suggestions...